"In whatever point of view these old ramparts are considered, they possess an imposing interest and confer incalculable benefits. To the invalid, the sedenatary student, or the man of business, occupied during the day in his shop or counting house; to the habitually indolent, who require excitement to necessary exercise, to all these, the the promenade on Chester walls have most inviting attractions, where they may breath all the salubrous winds of heaven in a morning or an evening walk. "In whatever point of view these old ramparts are considered, they possess an imposing interest and confer incalculable benefits. To the invalid, the sedenatary student, or the man of business, occupied during the day in his shop or counting house; to the habitually indolent, who require excitement to necessary exercise, to all these, the the promenade on Chester walls have most inviting attractions, where they may breath all the salubrous winds of heaven in a morning or an evening walk.

Here the enthusiastic antiquarian, who would climb mountains, ford rivers, explore the bowels of the earth, and, regardless of toil, and the claims of nature, exhaust his strength in the search for a piece of rusty cankered brass, or a scrap of Roman earthenware, can scarcely advance a dozen paces, but the pavement on which he treads, or some contiguous object, forces upon his observation the reliques of times of earliest date.

Nor can the philosophic moralist encompass our venerable walls without having his mind, comparing the splendid and gigantic works of antiquity with their present condition, strongly impressed with the mutations produced by the lapse of ages, and the perishing nature of all mundane greatness".

Joseph Hemingway: Panorama of the City of Chester 1836.

aving

read Lucian

the

Monk's comments

about

Chester,

here

are

some

extracts

from

the

accounts

of

other

travellers

who

have

passed

through

the

city

over

the

centuries. aving

read Lucian

the

Monk's comments

about

Chester,

here

are

some

extracts

from

the

accounts

of

other

travellers

who

have

passed

through

the

city

over

the

centuries.

We

preface

our

exploration

with

a

modern

translation

of The

Ruin,

the

first

English

meditation

on

old

stones:

the

Saxon

poet

strolls,

not

through

Chester-

the

Roman Deva-

but

immediately

post-Roman Aqua

Sulis (modern

Bath-

although

the

exact

location

is

disputed): "Down

brambled

streets,

past

oozing

pipes,

carved

walls

and

columns,

sculpted

heads-

and

seeing

in

them

not

something

mute,

but

a

society

like

his

own

writ

large,

a

place

of

weapons

and

gems

and

beery

halls" (Ronald

Wright: A

Scientific

Romance).

His

words

would

have

applied

equally

well

to

Deva

and

the

hundreds

of

other

abandoned

Roman

towns

and

fortresses

throughout

5th

century

Britain:

The city buildings fell apart, the works

Of giants crumble. Tumbled are the towers

Ruined the roofs, and broken the barred gate,

Frost in the plaster, all the ceilings gape,

Torn and collapsed and eaten up by age.

And grit holds in its grip, the hard embrace

Of earth, the dead-departed master-builders,

Until a hundred generations now

Of people have passed by. Often this wall

Stained red and grey with lichen has stood by

Surviving storms while kingdoms rose and fell.

And now the high curved wall itself has fallen.

The heart inspired, incited to swift action.

Resolute masons, skilled in rounded building

Wondrously linked the framework with iron bonds.

The public halls were bright, with lofty gables,

Bath-houses many; great the cheerful noise,

And many mead-halls filled with human pleasures.

Till mighty fate brought change upon it all. |

Slaughter was widespread, pestilence was rife,

And death took all those valiant men away.

The martial halls became deserted places,

The cities crumbled, its repairers fell,

Its armies to the earth. And so these halls

Are empty, and this red curved roof now sheds

Its tiles, decay has brought it to the ground,

Smashed it to piles of rubble, where long since

A host of heroes, glorious, gold-adorned,

Gleaming in splendour, proud and flushed with wine,

Shone in their armour, gazed on gems and treasure,

On silver, riches, wealth and jewellery,

On this bright city with its wide domains.

Stone buildings stood, and the hot streams cast forth

Wide sprays of water, which a wall enclosed

In its bright compass, where convenient

Stood hot baths ready for them at the centre.

Hot streams poured forth over the clear grey stone,

To the round pool and down into the baths. |

Despite

the

centuries

of

occupation,

today,

we

possess

no

surviving

Roman

references

to

the

fortress

of

Deva

apart

from

its

listing

in

the Antonine

Itinerary and

all

the

'Dark

Age'

references

are

mere

mentions

rather

than

descriptions.

The

author

of

the

early

ninth

century History

of

the

Britons,

sometimes

attributed

to

Nennius,

lists Cair

Legion as

one

of

the

twenty

eight

cities

of

Britain-

not

Caerlleon-ar-Wysg

in

South

Wales,

by

the

way,

as

that's

also

listed

as Cair

Legion

guar

Uisc:

"Camp

of

the

Legion

on

the

(river)

Usk". Despite

the

centuries

of

occupation,

today,

we

possess

no

surviving

Roman

references

to

the

fortress

of

Deva

apart

from

its

listing

in

the Antonine

Itinerary and

all

the

'Dark

Age'

references

are

mere

mentions

rather

than

descriptions.

The

author

of

the

early

ninth

century History

of

the

Britons,

sometimes

attributed

to

Nennius,

lists Cair

Legion as

one

of

the

twenty

eight

cities

of

Britain-

not

Caerlleon-ar-Wysg

in

South

Wales,

by

the

way,

as

that's

also

listed

as Cair

Legion

guar

Uisc:

"Camp

of

the

Legion

on

the

(river)

Usk".

Right: Just such an abandoned street as was described in The Ruin, seen in Ephesus, Turkey. Photograph by the author.

The Annales

Cambrie ('Annals

of

Wales')

mention

a

"Synod

of

The

City

of

the

Legion"

in

a

year

which

might

be

603

or

606-

they

followed

an

eccentric

chronology

all

of

their

own,

and

it's

often

difficult

to

place

an

event

into

the

correct

calendar

year.

Everyone

seems

to

agree

that

this

'City

of

the

Legion'

was

Chester

and

that

the

Synod

is

the

one Bede mentions

when

describing

how

the

British

church

rejected Saint

Augustine's authority.

In

Bede-

who

refers

to

"The

City

of

the

Legion,

which

is

called

Carlegion

by

the

Britons

and

Legacaistir

by

the

English"-

this

then

becomes

the

cause

of

the

Battle

of

Chester

(in

the

year

613

or

616),

when

the

monks

from Bangor Isycoed (Bangor-on-Dee) were

slaughtered

by

the

pagan

Aethelfrith.

In

the Anglo-Saxon

Chronicle,

at

the

end

of

the

entry

for

the

year

893,

we

read,

"on

anre

westre

ceastre

on

Wirhealum,

seo

is

Legaceaster

gehaten"-"in

a

deserted

fort

on

Wirral,

which

is

called

Legaceaster".

Arguments

have

raged

for

years

about

whether

the

old

fortress

had

been

deserted

since

the

end

of

the

Roman

period

or

if

its

inhabitants

had

recently

fled

at

the

approach

of

the

Danish

army.

There is

also

the

possibility

that

the

local

population

actually

colluded

with

the

Danes,

letting

them

in-

something

the

writer

of

the

Chronicle

would

evidently

rather

pass

over

in

silence!

The

archaeological

evidence,

however,

shows

that

there

were

certainly

people

living

in

the

fort

before

the

arrival

of

the

Danish

army.

In

972

(really

the

following

year),

Manuscript

E

of

the Anglo

Saxon

Chronicle says-

"And

soon

after

that

(his

consecration

at

Bath

at

Pentecost),

the

king

led

all

his

navy

(ship-army)

to

Legeceaster.

And

there

came

six

kings

to

him,

and

all

with

promises

that

they

would

forever

be

his

vassals

on

sea

and

on

land". Then,

in

the

year

1000

"Her

on

issum

geare

se

cyng

ferde

in

to

Cumerlande...

his

scipu

wendon

ut

abuton

Legceastre"-

"In

this

year,

the

King

went

into

Cumberland

(probably

Lancashire!).

And

his

ships

went

out

from

Legceaster".

Five

hundred

years

after

the

Legions

withdrew

from

Deva,

their

Saxon

successors

knew

the

city

as Legecaester,

a

translation

of

part

of

the

British

(Welsh) Caer

Lleon

Vawr

ar

Ddyfrdwy or

'Camp

of

the

great

Legion

on

the

Dee'-

also

Caerleon-ar-Dour. Five

hundred

years

after

the

Legions

withdrew

from

Deva,

their

Saxon

successors

knew

the

city

as Legecaester,

a

translation

of

part

of

the

British

(Welsh) Caer

Lleon

Vawr

ar

Ddyfrdwy or

'Camp

of

the

great

Legion

on

the

Dee'-

also

Caerleon-ar-Dour.

A

fascinating

and

convincing

body

of

evidence

was

propounded

by Robert

Stoker in

his

book The

Legacy

of

Arthur's

Chester (1965)

which

points

out

that

there

were

actually two Caerleons

(see Henry

Bradshaw's poem

below)

and,

after

the

departure

of

the

Romans,

it

was

Chester

that

became

the

ecclesiastical

and

civil

capital

of

the

Kings

of

Britain

and

the

city

of

the

coronation

of

the

not-so-legendary

King

Arthur, not Caerleon-on-Usk (Isca)

in

South

Wales.

The

confusion

apparently

lies

with

Arthur's

medieval

chronicler, Geoffrey

of

Monmouth,

whose

patron,

Robert

of

Gloucester,

was

Lord

of

the

Monmouth

Marches,

where

Caerleon-on-Usk

is A

fascinating

and

convincing

body

of

evidence

was

propounded

by Robert

Stoker in

his

book The

Legacy

of

Arthur's

Chester (1965)

which

points

out

that

there

were

actually two Caerleons

(see Henry

Bradshaw's poem

below)

and,

after

the

departure

of

the

Romans,

it

was

Chester

that

became

the

ecclesiastical

and

civil

capital

of

the

Kings

of

Britain

and

the

city

of

the

coronation

of

the

not-so-legendary

King

Arthur, not Caerleon-on-Usk (Isca)

in

South

Wales.

The

confusion

apparently

lies

with

Arthur's

medieval

chronicler, Geoffrey

of

Monmouth,

whose

patron,

Robert

of

Gloucester,

was

Lord

of

the

Monmouth

Marches,

where

Caerleon-on-Usk

is

It

seems

that

Geoffrey,

doubtess

partly

in

order

to

please

his

Lord,

attributed

all

references

dealing

with

'Caerleon-ar-Dour'

(Chester)

to

'Caerleon'

without

qualifying

which

one

was

meant.

Historians

have

ever

since,

for

example,

been

crediting

Isca

with

having

an

archbishop

since

AD 180

because

the

local

boy

of

Monmouth

said

so

in

1100,

and

nobody

has

ever

checked

the

record...

Whatever

the

case,

think

of

the

still-magnificent

old

fortress

on

the

Dee

as

you

read

Geoffrey's

description

of

Arthur's

coronation

in

the

early

years

of

the

seventh

century:

"From

the

approach

of

the

Feast

of

Pentecost,

Arthur...

resolved

the

whole

magnificent

court,

to

place

the

crown

upon

his

head

and

to

invite

all

the

Kings

and

Dukes

under

his

subjection

to

the

solemnity...

He

pitched

upon

the

City

of

Legions

as

a

proper

place

for

this

purpose,

for

beside

the

great

wealth

of

it,

above

all

other

cities

its

situation...

was

most

pleasant,

for

on

one

side

it

was

washed

by

the

noble

river

so

that

Kings

and

Princes

from

countries

beyond

theseas

might

have

the

convenience

of

sailing

up

to

it;

on

the

other

side

the

beauty

of

the

meadows

and

groves,

and

the

magnificence

of

the

Royal

palaces

with

lofty

gilded

roofs

that

adorned

it

may

even

rival

the

grandeur

of

Rome.

There

came...

the

Archbishops

of

the

three

Metropolitan

Sees-

London,

York

and

Dubricius

of

the

City

of

the

Legions,

this

Prelate

who

was

Primate

of

Britain

and

Legate

of

the

Apostolic

See,

was

so

eminent

for

his

piety

that

by

his

prayers

he

could

cure

any

sick

person."

In connection with the above, an interesting article, entitled "Historians locate King Arthur's Round Table" appeared in The Sunday Telegraph, 11th July 2010: In connection with the above, an interesting article, entitled "Historians locate King Arthur's Round Table" appeared in The Sunday Telegraph, 11th July 2010:

"Researchers exploring the legend of Britain’s most famous Knight believe his stronghold of Camelot was built on the site of a recently discovered Roman amphitheatre in Chester.

Legend has it that his Knights would gather before battle at a round table where they would receive instructions from their King. But rather than it being a piece of furniture, historians believe it would have been a vast wood and stone structure which would have allowed more than 1,000 of his followers to gather.

Historians believe regional noblemen would have sat in the front row of a circular meeting place, with lower ranked subjects on stone benches grouped around the outside. They claim rather than Camelot being a purpose built castle, it would have been housed in a structure already built and left over by the Romans.

Camelot historian Chris Gidlow said: “The first accounts of the Round Table show that it was nothing like a dining table but was a venue for upwards of 1,000 people at a time. We know that one of Arthur’s two main battles was fought at a town referred to as the City of Legions. There were only two places with this title. One was St Albans but the location of the other has remained a mystery.”

The recent discovery of an amphitheatre with an execution stone and wooden memorial to Christian martyrs, has led researchers to conclude that the other location is Chester. Mr Gidlow said: “In the 6th Century, a monk named Gildas, who wrote the earliest account of Arthur’s life, referred to both the City of Legions and to a martyr’s shrine within it. That is the clincher. The discovery of the shrine within the amphitheatre means that Chester was the site of Arthur’s court and his legendary Round Table.”

This material was apparently expanded into a TV programme that was aired on the History Channel during July 2010. This material was apparently expanded into a TV programme that was aired on the History Channel during July 2010.

There are, of course, all manner of problems with the above, not least the twice-stated statement regarding the "newly discovered" Chester amphitheatre- which actually occured in 1929, as you'll know if you've followed our brief history of the monument. Just one more example concerns that 'shrine'- actually altar- within the amphitheatre, which, as is known to everyone that has visited it, is dedicated to Nemesis, patron goddess of amphitheatres and goddess of retribution, and was placed there by the Centurion Sextus Marcianus "after a vision". It has nothing at all to do with 6th century martys. You can see a picture of it and learn more on the first page of our story of the amphitheatre.

* Go here to

read T.

H.

White's lively

description

of

Arthur's

entry

into

'Carlion'

from

his

great

novel The

Once

and

Future

King.

Half

a

millennium

later,

Chester

was

the

last

city

in

England

to

fall

to William

the

Conqueror's army-

a

full

three

years

after

the

Battle

of

Hastings.

In

around

1086,

the

city

was

visited

by

William's

commissioners

for

assessment

as

part

of

the

great Domesday

Survey. Half

a

millennium

later,

Chester

was

the

last

city

in

England

to

fall

to William

the

Conqueror's army-

a

full

three

years

after

the

Battle

of

Hastings.

In

around

1086,

the

city

was

visited

by

William's

commissioners

for

assessment

as

part

of

the

great Domesday

Survey.

Soon

after

the

completion of

the

Domesday

Book

was

born William

of

Malmesbury (c.1095-1143),

a

monk

of

that

Abbey,

who

was

of

mixed

Anglo-Norman

birth.

He

spent

most

of

his

life

as

a

librarian

at

Malmesbury,

but

he

also

travelled

widely

throughout

England.

He

is

considered

the

first

English

historian

after Bede (c.672-735)

William

wrote

this

account

aroundthe year

1125... Soon

after

the

completion of

the

Domesday

Book

was

born William

of

Malmesbury (c.1095-1143),

a

monk

of

that

Abbey,

who

was

of

mixed

Anglo-Norman

birth.

He

spent

most

of

his

life

as

a

librarian

at

Malmesbury,

but

he

also

travelled

widely

throughout

England.

He

is

considered

the

first

English

historian

after Bede (c.672-735)

William

wrote

this

account

aroundthe year

1125...

"Chester

is

called

the

city

of

the

Legions because

the

veterans

of

the

Julian

legions

were

settled

there.

It

adjoins

the

country

of

the

northern

Britons.

The

region,

like

much

of

the

north,

is

barren

and

unproductive

of

cerials,

especially

corn,

though

it

is

rich

in

beasts

and

fish.

The

natives

greatly

enjoy

milk

and

butter;

those

who

are

richer

live

on

meat

and

are

much

attached

to

bread

made

from

barley

and

wheat.

Goods

are

exchanged

between

Chester

and

Ireland,

so

that

what

the

nature

of

the

soil

lacks,

is

supplied

by

the

toil

of

the

merchants.

In

the

city

there

was

once

a

monastery

of

holy

nuns,

now

re-established

for

monks

by

Hugh,

Earl

of

Chester."

In

1189 Gerard

Barry,

better

known

as Giraldus

Cambrensis ('Gerald

of

Wales'),

accompanied

Archbishop

Baldwin

on

an

epic

journey

around

Wales,

preaching

the

Crusades,

and

kept

a

record

of

his

impressions.

He

wrote

of

Chester: In

1189 Gerard

Barry,

better

known

as Giraldus

Cambrensis ('Gerald

of

Wales'),

accompanied

Archbishop

Baldwin

on

an

epic

journey

around

Wales,

preaching

the

Crusades,

and

kept

a

record

of

his

impressions.

He

wrote

of

Chester:

"A

genuine

city

of

the

Legions,

surrounded

by

walls

of

brick,

in

which

many

remains

of

its

pristine

grandeur

are

still

apparent,

namely

immense

palaces,

a

gigantic

tower,

beautiful

baths,

remains

of

temples

and

sites

of

theatres,

almost

entirely

enclosed

by

excellent

walls

in

part

remaining.

Also

both

within

and

without

the

circumference

of

the

walls

subterranean

constructions,

watercourses,

vaulted

with

passages.

You

may

also

see

furnaces

constructed

with

wonderful

art,

the

narrow

sides

of

which

inhale

heat

by

concealed

spiracles."

He

added

that

he

saw

there

"an

animal

partly

an

ox

and

partly

a

stag,

and

a

woman,

born

without

arms,

who

could

sew

with

her

feet"...

Ranulf

Higden, also

a

Benedictine monk of

St.Werburgh's

Abbey,

who

died

about

1364,

was said to have been the author of the celebrated Chester Mystery Plays but he is better remembered for his Polychronicon.

Originally a compilation from old chronicles and books upon natural history and other subjects penned by one Roger, a fellow monk of the Abbey at the beginning of the 14th century, Higden expanded greatly upon this, dealing with the countries of the known world, especially Britain, and a history of the world from the Creation down to his own time.

The work was first translated into English in 1387 and later added to by the famous early printer William Caxton, who continued the narrative down to the year 1460. He printed this expanded translation "a lytel embelysshed fro tholde" in 1482. It

remained

the

standard

reference

work

for

hundreds

of

years. Only 26 copies of the book are know to exist, of which only two are perfect. This

description

is

a

digression

in

an

early

section

of

the

work

and

is

quoted

from

the

edition

printed

by

Winkyn

de

Worde

(a

pupil

of

Caxton)

around

1495... Ranulf

Higden, also

a

Benedictine monk of

St.Werburgh's

Abbey,

who

died

about

1364,

was said to have been the author of the celebrated Chester Mystery Plays but he is better remembered for his Polychronicon.

Originally a compilation from old chronicles and books upon natural history and other subjects penned by one Roger, a fellow monk of the Abbey at the beginning of the 14th century, Higden expanded greatly upon this, dealing with the countries of the known world, especially Britain, and a history of the world from the Creation down to his own time.

The work was first translated into English in 1387 and later added to by the famous early printer William Caxton, who continued the narrative down to the year 1460. He printed this expanded translation "a lytel embelysshed fro tholde" in 1482. It

remained

the

standard

reference

work

for

hundreds

of

years. Only 26 copies of the book are know to exist, of which only two are perfect. This

description

is

a

digression

in

an

early

section

of

the

work

and

is

quoted

from

the

edition

printed

by

Winkyn

de

Worde

(a

pupil

of

Caxton)

around

1495...

" CHESTRE,

where

this

cronicle

presente

was

laborede,

in

the

coste

of

Wales

betwene

two

armes

of

the

sea

whiche

be

callede

Dye

and

Meresie

(Dee

and

Mersey)

whiche

was

the

chiefe

cite

of

Northe

Wales

in

the

tyme

of

Britones,

the

firste

founder

of

whom

is

not

knowen.

For

hit

scholde

seme

to

a

man

beholdenge

the

fundacion

of

hit

that

werke

to

be

rather

of

the

labor

of

gigantes,

other

Romanes,

then

of

Britones.

That

cite

was

callede

somme

tyme

in

the

langage

of

Britones,

Caerelyon,

in

Latyn

Legecestria,

and

hit

is

callode

now

Chestre,

other

the

Cite

of

Legiones,

in

that

the

legiones

of

knyghtes tariede

ther

in

wynter,

whom

Julius

Cesar

sende

to

Yrlonde

to

subdue

hit

to

hym.

This

cite

habundethe

in

euery

kynde

of

vitelles,

thaughe

William

Malmesbury

dreamede

in

other

wise,

as

in

corne,

flosche,

fische,

and

specially

in

salmones,

whiche

cite

recoyvethe

and

sendethe

from

it

diuerse

marchandise,

whiche

hathe

nye

to

hit

waters

of

salte

and

metalles.

That

cite,

somme

tyme

destroyede

by

men

of

Northumbrelonde,

but

reedificate

by

Elfleda,

lady

of

the

marches,

hathe

under

the

erthe

voltes

to

be

meruailede

thro

the

werke

of

ston,

and

other

grete

stones

conteynenge

the

names

and

pryntes

of

Julius

Cesar,

and

of

other

nowble

men,

with

the

wrytyinge

about."

Higden

was

buried

in

the

South

Choir

Aisle

of

the

Abbey.

In

1873

his

tomb

was

opened

to

reveal

"the

exact

form

of

a

body

still

wrapped

in

coarse

woolen

cloth

of

a

reddish-brown".

"I

cannot

repeat

perfectly

my

pater

noster

as

the

priest

it

singeth,

But

I

can

repeat

rhymes

of

Robin

Hood

and

Randal,

Earl

of Chester"

Langland:

Piers

Plowman

The

great

Welsh

bard Lewys

Glyn

Cothi (c.1420-1489),

whose

works

re-awoke

a

consciousness

of

nationhood

among

the

war-torn

and

subjugated

people

of

Wales,

lived

for

a

time

in

Chester

until

he

was

evicted,

perhaps

as

a

result

of

the

law

which

denied

Welshmen

the

right

to

settle

in

the

boroughs-

or

maybe

as

a

result

of

his

having

married

a

widow

from

the

city

without

the

consent

of

the

burgesses. The

great

Welsh

bard Lewys

Glyn

Cothi (c.1420-1489),

whose

works

re-awoke

a

consciousness

of

nationhood

among

the

war-torn

and

subjugated

people

of

Wales,

lived

for

a

time

in

Chester

until

he

was

evicted,

perhaps

as

a

result

of

the

law

which

denied

Welshmen

the

right

to

settle

in

the

boroughs-

or

maybe

as

a

result

of

his

having

married

a

widow

from

the

city

without

the

consent

of

the

burgesses.

He

referred

to

his

experiences

in

his

poem The

Coverlet:

Go, complaint, to Gwynedd's sun,

I complain of the mongrels,

So crafty they were, so cold,

Mobs in the town of Chester.

It's they who plundered my house

Of my bed and fine bedspread,

And they have left me barer

Than salmon swimming a stream. |

Whatever

the

reason,

Cothi

ever

after

bore

considerable

ill-will

towards

the

city

and

its

inhabitants,

as

powerfully

illustrated

in

another

poem, The

Sword,

from

which

we

present

the

following

extracts:

The

lion

with

the

golden

mane

Who

lives

down

in

Croes

Oswallt,

Mighty

Dafydd

ap

Gutun,

May

he

never

grow

white

hair.

This

request

I

make

of

Dafydd,

It's

given

before

I

ask,

Not

for

gold,

and

not

for

land,

A

sword,

one

of

his

weapons.

It

has,

for

proper

gripping,

A

short

hilt

round

as

a

cask;

There's

a

white-corniced

cover,

And

a

clamp

like

a

round

ring.

There's

a

belt,

forked

and

crooked,

A

wooden

sheath

and

bent

cross.

By

the

cross

it's

so

fashioned,

It

is

broader

than

a

hand.

It

has

a

point

that's

as

thin

As

a

wing's

tip,

a

needle,

A

thorn

like

a

fine-honed

dart,

Keen

steel,

two

feet

three

inches,

Blest

cross

against

boorish

boys,

Protecting

cross,

stripped

naked.

|

Blue

blade,

when

it

is

displayed,

Sheet

of

glass

like

a

razor,

A

light

it

is,

a

long

crutch,

And

like

true

gold

it

glitters,

Killer,

like

a

Jew's

dagger,

And

keen

as

a

lion's

tooth.

This

I

request

of

Dafydd,

If

this

request

he

will

grant,

I

will

shave,

by

Saint

Non's

hand,

All

of

the

lads

of

Chester.

On

every

churl

I'll

whet

it,

Rib

of

steel,

if

I

come

there.

Not

one

leaves,

till

Saint

Dwyn's

Feast,

The

hot

town

head

unbroken.

I'll

carve,

if

I

come

near

them,

Twenty

thousand

naked

curs.

That

day,

after

drinking

wine,

I'll

wield

the

blade

of

Cyffin,

I'll

deal

with

my

hands

a

hurt

To

that

two-faced

town

yonder.

From

the

towns

of

Rhos

at

dawn,

By

nightfall

to

dark

Chester:

Let

me

kill,

if

my

day

arrives,

With

Dafydd's

sword

two

thousand! |

Fellow Welsh poet Guto'r

Glyn observed,

as

quoted

by George

Borrow that

the

women

of

London

itself

were

never

more "carn

strumpets" than

those

of

Chester..

Henry

Bradshaw (d.

1513),

born

in

Chester

and

educated

at

Gloucester

College,

Oxford,

was

also

a

monk

of

St.Werburgh's Abbey.

He

wrote

a a

verse

life

of

St.Werburgh

in

1500 and a

chronicle

of

Chester-

now sadly

lost- the De Antiquitate et Magnificentia Urbis Cestriae in the year of his death, 1513. This

extract

is

taken from the earlier work, which

survives

only

in

a

printed

edition

of

1521,

of

which

only

five

copies

are

known... Henry

Bradshaw (d.

1513),

born

in

Chester

and

educated

at

Gloucester

College,

Oxford,

was

also

a

monk

of

St.Werburgh's Abbey.

He

wrote

a a

verse

life

of

St.Werburgh

in

1500 and a

chronicle

of

Chester-

now sadly

lost- the De Antiquitate et Magnificentia Urbis Cestriae in the year of his death, 1513. This

extract

is

taken from the earlier work, which

survives

only

in

a

printed

edition

of

1521,

of

which

only

five

copies

are

known...

"This

'cite

of

legions'

so

called

by

the

Romans,

Nowe

is

nominat

in

latine

of

his

proprete

Cestria

quasi

castria,

of

honour

and

pleasance:

Proued

by

the

buyldynge

of

olde

antiquite

In

cellers

and

lowe

voultes,

and

halles

of

realte

Lyke

a

comly

castell,

myghty,

stronge

and

sure,

Eche

house

like

a

toure,

somtyme

of

great

pleasure.

Of

frutes

and

cornes

there

is

a

great

habundaunce,

Woddes,

parkes,

forestes,

and

beestis

of

venare,

Pastures,

feeldes,

comons,

the

cite

to

auaunce,

Waters,

pooles,

pondes,

of

fysshe

great

plente;

Most

swete

holsome

ayre

by

the

water

of

dee;

There

is

great

marchandise,

shyps,

and

wynes

strang,

With

all

thyng

of

pleasure

the

citezens

amonge". |

And here

is

Bradshaw's

description

of

the

two

old

Roman

fortresses

sharing

the

British

(Welsh)

name

of Caerleon-

"Two

Cities

of

Legions

in

chronicles

we

find;

One

in

South

Wales

in

the

time

of

Claudius

Called

Caerusk

by

Britons

had

in

mind;

Or

else

Caerleon

built

by

King

Belinus:

Where

sometimes

was

a

Legion

of

Knights

Chivalrous.

This

City

of

Legions

was

whilom

the

Bishop's

See

To

all

South

Wales

nominate

Venedocie.

Another

City

of

Legions

we

find

also

In

the

West

part

of

England

by

the

waters

of

Dee

Called

Caerleon

of

Britons

long

ago,

After

named

Chester

by

great

authority...

This

City

of

Legions

so

called

by

Romans...

Proved

by

buildings

of

old

antiquity...

Each

house

like

a

castle,

sometimes

of

great

pleasure" |

John

Leland wrote

of

Cheshire

folk John

Leland wrote

of

Cheshire

folk in

his Itinerary of

1540:

"The

people

of

the

countrey

are

of

nature

very

gentle

and

courteous,

ready

to

help

and

further

one

another;

in

religion

very

zealous,

howbeit

somewhat

addicted

to

superstition.

Otherwise

they

are

of

the

stomache

stout,

body

and

hardy;

withal

impatient

of

wrong,

and

ready

to

resist

the

enemy

or

stranger

that

shall

invade

their

countrey.

So

have

they

always

been

true,

faithful

and

obedient

to

their

supervisors

insomuch

that

it

cannot

be

said

that

they

have

at

any

time

stirred

one

spark

of

rebellion

either

against

the

King's

Majesty,

or

against

their

own

peculiarhord

or

Government"   The

following

lengthy

and

interesting

description was

written

in

about 1575,

and

is

taken

from

an

account

of

Cheshire

by William

Smith (c

1550-1618),

a

local

man

who

lived

for

periods

in

London

and

Nuremberg,

and

became

a

herald

(rouge

dragon

pursuivant)

in

1597... The

following

lengthy

and

interesting

description was

written

in

about 1575,

and

is

taken

from

an

account

of

Cheshire

by William

Smith (c

1550-1618),

a

local

man

who

lived

for

periods

in

London

and

Nuremberg,

and

became

a

herald

(rouge

dragon

pursuivant)

in

1597...

"The

Walles

of

the

Cittie,

containe

at

this

present

day

in

Circuite

Two

English

myles.

Within

the

which

in

some

places,

there

is

certayne

void

ground

and

Corne

feilds,

Wherby

(as

also

certaine

Ruines

of

Churches,

and

such

Lyke

great

places

of

Stone)

it

Appeareth

that

the

same

was,

in

old

tyme

all

Inhabited.

But

Looke

what

it

wanteth

at

this

day

within

the

walles:

It

hath

without,

In

very

faire

and

Large

Suburbes"

Right:

Eastgate

Row

North

by

George

Cuitt

(1779-1854)

"It

hath

foure

principall

gates.

The

Estyate,

towards

the

Est.

The

Bridge

gate,

towards

the

Sowth.

The

Watergate

towardes

the

West.

And

the

Northyate

towardes

the

North.

These

gates

in

tymes

past,

and

yet

still,

according

to

an

Antient

order

vsed

here

in

this

Cittie:

Are

in

the

protection

or

deffence,

of

dyvers

noble

men,

Which

hold,

or

have

their

Landes

Lying

within

the

Countie

pallatine.

As

first,

the

Erle

of

oxford,

had

(till

of

Late

yeares,

but

now

Sir

Christopher

Hatton)

the

Estyate.

The

Erle

of

Shrewsbury,

the

Bridge

gate.

The

Erle

of

Darby

hath

the

Watergate,

who

in

the

Right

of

the

Castell

of

Hawarden

(not

farr

of)

is

Steward

of

the

Countie

pallatine.

And

the

northyate

belongeth

to

the

Cittie,

where

they

kepe

their

prisoners.

The

Estyate,

is

the

fayrest

of

all

the

Rest.

ffrom

which

gate

to

the

Barres

(which

are

also

of

Stone)

I

ffynd

to

be

160

paces

of

geometrie,

And

from

the

Barrs,

to

Boughton

almost

as

much.

Besydes

these

4

principall

gates:

There

are

certaine

other

lesser,

Lyke

postern

gates,

And

namely

St.

John's

gate,

(

Newgate

or

Wolfgate)

betwene

Estyate

and

Bridge

gate,

So

called,

because

it

goeth

to

the

said

Church

of

St.

John,

which

standeth

without

the

walles.

The

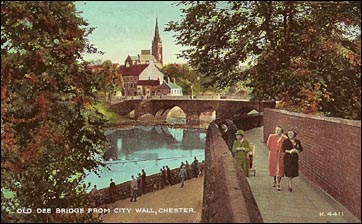

Bridge

gate,

is

at

the

Southpart

of

the

Cittie,

At

the

entring

of

the

bridge

(Comonly

called

Dee

Bridge)

which

Bridge

is

builded

all

of

Stone,

of

viij.

Arches

in

length.

Att

the

furthest

end

wherof,

is

also

a

gate.

And

without

that

(on

the

other

syde

of

the

water)

The

Suburbes

of

the

Cittie,

called

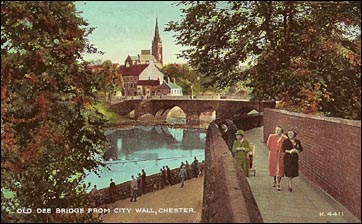

Handbridge. The

Bridge

gate,

is

at

the

Southpart

of

the

Cittie,

At

the

entring

of

the

bridge

(Comonly

called

Dee

Bridge)

which

Bridge

is

builded

all

of

Stone,

of

viij.

Arches

in

length.

Att

the

furthest

end

wherof,

is

also

a

gate.

And

without

that

(on

the

other

syde

of

the

water)

The

Suburbes

of

the

Cittie,

called

Handbridge.

Thc

Watergate,

is

on

the

west

syde

of

the

Cittie.

whereunto

in

tymes

past,

great

Shipps

and

vessells

might

come,

at

a

full

Sea.

But

now

scarce

small

boates

are

able

to

come,

The

Sandes

have

so

Choaked

the

Chanell.

And

although

the

Citezens

have

bestowed

marvelous

great

charges,

in

building

The

New

Tower,

which

standeth

in

the

very

River,

betwene

this

gate,

and

Northyate:

yet

all

will

not

help.

And

therefore

all

the

Shipps,

do

come

to

a

place,

called

The

New

Kay,

6.

myles

from

the

Cittie.

(Neston)

Left: the coat of arms of the City of Chester. The Latin motto, Antiqui Colant Antiquum Dierum translates as 'Let the ancients worship the ancient of days'.

The

Castle

of

Chester,

Standeth

on

a

Rocky

hill,

within

the

Wall

of

the

Cittie,

not

farr

from

the

Bridge.

Which

Castell,

is

a

place

having

privelege

of

it

selff.

And

hath

a

Constable.

The

building

thereof

seemeth

to

be

very

Ancient.

At

the

first

coming

in,

is

The

gate

house,

which

is

a

pryson

for

the

whole

County,

having

dyuers

Roumes

and

Lodgings.

And

hard

within

the

gate,

is

A

howse,

which

was

somtimes

the

Exchekor:

but

now

the

Custome

house.

Not

farr

from

thence,

in

the

base

court,

is

A

deepe

well,

and

thereby,

Stables

and

other

howses

of

office.

On

the

left

hand

is

A

Chapell.

And

hardby

adioyning

thervnto,

The

goodly

ffayre

and

Largo

Shyre

hall.

newly

Repayred.

Where

all

matters

of

Law,

touching

the

Countie

pallatine,

are

hard,

and

judically

determyned.

And

at

the

end

thereof

is

The

Brave

new

Exchequer,

for

the

said

Countie

pallatine.

All

these

are

in

the

Base

Court.

Then

there

is

A

draw

Bridge

into

the

Innerward,

wherein

are

dyvers

fayre

and

pleasant

Lodgings,

for

the

justices,

When

they

come.

And

herein

The

Constable

hym

selff

dwelleth.

The

Theeves

and

Fellons,

are

Arraigned

in

the

said

Shire

hall,

And

being

Condemned:

Are

by

the

Constable

of

the

Castell,

or

his

deputie,

delyvered

to

the

Shireffs

of

the

Cittie,

a

Certayne

distance,

without

the

Castlegate,

At

a

Stone,

called

The Glovers

Stone ffrom

which

place,

The

said

Sheriffs

do

Convay

them

throwgh

the

Citty,

to

the

place

of

Execution,

called

Boughton.

PARISH

CHURCHES

IN

CHESTER

Tho

Cittie

is

devyded

into

ix

Parishes.

The

first

wherof

is

named

St.

Werburgs.

otherwise

called

The

Abbay,

or

Minster,

And

is

The

Cathedrall

Church,

having

the

parish

Church

in

the

South

yle

of

the

same.

This

is

a

goodly,

fayre

and

Large

Cross

Church,

having

a

square

Steple

in

the

middest,

And

at

the

West

end,

is

A

Steple

begon,

but

not

halff

finished.

Hardby

adioyning,

is

the

Bishopps

pallace,

and

not

farr

of

The

Deanes

howse. PARISH

CHURCHES

IN

CHESTER

Tho

Cittie

is

devyded

into

ix

Parishes.

The

first

wherof

is

named

St.

Werburgs.

otherwise

called

The

Abbay,

or

Minster,

And

is

The

Cathedrall

Church,

having

the

parish

Church

in

the

South

yle

of

the

same.

This

is

a

goodly,

fayre

and

Large

Cross

Church,

having

a

square

Steple

in

the

middest,

And

at

the

West

end,

is

A

Steple

begon,

but

not

halff

finished.

Hardby

adioyning,

is

the

Bishopps

pallace,

and

not

farr

of

The

Deanes

howse.

Tho

Second

parish

Church,

is

called

St.

Johns.

and

is

hard

without

the

Walles

vppon

tho

banck

of

the

River

Dee.

A

very

fayre

and

Large

Church,

with

a

fayre

brode

Steple

at

the

West

end

therof,

Which

Steple

the

yeare

past

Anno

1574,

did

halff

of

it

fall

downe,

from

the

very

topp

to

the

Bottome.

Two

squares

did

fall

downe,

And

two

squares

do

stand

still.

but

it

is

building

upp

agayne.

Right: a holiday advertisment for Chester which appeared in the Radio Times, 5th May 1939, just before the start of World War Two.

St.

Peters,

at

the

high

Cross,

In

the

middest

of

the

Cittie,

A

ffayre

Church,

with

a

Spyre

Steple,

vnderneath

which

Church

is

The

Pendice,

wherof

more

shalbe

said,

shortly

after.

St.

Trinities,

betwene

St.

Peters

Church,

and

the

Watergate,

A

ffayre

Church,

with

a

Spyre

Steple

also.

St.

Michaells,

in

the

Bridge

Strete.

St.

Brydes,

Right

over

against

St.

Michaells.

St.

Olaffs,

comonly

called St.Tolas,

in

the

same

streete

nerer

to

the

Bridge.

St.

Maries,

on

the

Hill,

by

the

Castle

gate,

a

very

ffayre

[sic]

with

a

square

brode

Steple.

In

which

Church

are

certayne

fayre

Tombes,

of

dyvers

gentlemen,

and

ospecially

of

the

Troutbecks,

Who

(as

it

should

appeare)

Were

ffounders

therof.

St.

Martins,

not

farr

from

the

freres,

towards

the

west

part

of

the

Cittie.

St.

Thomas,

without

Northyate.

OF

THE

MAIOR,

ALDERMEN

AND

SHERIFFS

OF

THE

CITTIE,

ETC.

The

Estate

that

the

Maior

of

Chester

kepeth

is

great.

ffor

he

hath

both

Swordbearer,

Macebearer,

Sergeants

with

their

Silver

Maces,

in

as

good

and

Decent

order,

as

in

any

other

Cittie

of

England.

His

howsekeping

accordingly,

but

not

so

Chargeable,

as

in

some

other

Citties,

because

all

things

are

bettor

cheape

there.

He

Remayneth

most

part

of

the

day,

at

a

place

called

The

Pendice.

(demolished

1803)

Which

is

a

brave

place,

builded

for

the

purpose,

at

the

High

Cross,

vnder

St.

Peters

Church.

And

in

the

Middest

of

the

Cittie,

In

such

sort,

that

a

man

may

stand

therein,

and

see

into

the

Marketts,

or

4.

principall

streets

of

the

Cittie.

There

was

wont

to

sitt

also

(in

a

Roume

adioyning)

the

clarks

of

the

said

Maiors

Courts,

Where

all

actions

Were

entred,

Recognizances

made,

and

such

Iyke,

but

this

is

now

Removed

into

the

Comon

Hall

of

the

cittie.

There

is

none

chosen

alderman,

except

he

have

byn

first

Maior.

The

Sheriffs

(as

also

the

Maior)

on

the

workdaies,

do

go

in

fayre

Long

gownes,

Welted

with

velvet,

and

Whyte

staves

in

their

handes.

But

they

have

Violett

and

Scarlett

also,

for

festival

daies. There

is

none

chosen

alderman,

except

he

have

byn

first

Maior.

The

Sheriffs

(as

also

the

Maior)

on

the

workdaies,

do

go

in

fayre

Long

gownes,

Welted

with

velvet,

and

Whyte

staves

in

their

handes.

But

they

have

Violett

and

Scarlett

also,

for

festival

daies.

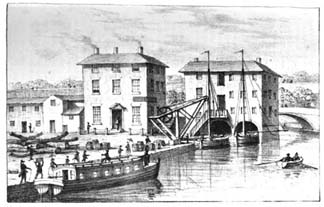

The Canal Packet House c.1840. The building to its right is today a fine pub, restaurant and live music venue known as Telford's Warehouse.

Not

farr

from

the

Pendice,

towardes

the

Abbay

Gate

is

The

Comon

Hall,

of

the

Cittie,

Which

is

a

very

great

howse

of

Stone.

And

serveth

in

stead

of

their

guildhall,

or

Towne

house.

The

Buildings

of

the

Cittie

are

very

Antient.

And

the

howses

build

in

such

sort:

that

a

man

may

go

dry,

from

one

part

of

the

Cittie,

to

another,

and

never

come

in

the

street,

But

go,

as

it

were

in

galleries,

which

they

call

The

Roes

which

have

Shopps,

on

both

sydes,

and

vnderneath,

with

dyvors

stayres

to

go

vpp

and

downe,

into

the

streets.

Which

maner

of

building,

I

have

not

hard

of,

in

any

p]ace

of

Christendome.

Some

will

ay,

that

the

Lyke

is

at

Padua

in

Italy.

But

that

is

not

so,

for

the

howses

at

Padua,

are

builded,

as

tho

Suburbes

of

this

Cittie

be,

that

is

on

the

ground,

vppon

posts,

that

a

man

may

go

dry

Vnderneth

them,

Lyke

as

they

are

at

Billings

gate

in

London.

But

nothing

Lyke

to

these

Roes.

It

is

a

goodly

sight,

to

see

the

nomber

of

fayre

Shopps

that

are

in

these

Roes,

of

Mercers,

grocers,

Drapers

and

Haberdashers.

Especially

in

the

Street

called

the

Mercers

Row.

Which

Street,

with

the

Bridgestreet

(being

all

one

street)

reacheth

from

the

High

Cross,

to

the

Bridge,

in

Length

380

paces

of

geometry,

Which

is

above

a

quarter

of

A

myle.

There

are

certayne

Conduits

of

freshwater.

And

now

of

Late

(following

the

example

of

London)

they

have

builded

one,

at

the

High

Cross,

in

the

middest

of

the

Cittie,

And

bring

the

water

to

it,

from

Boughton"

Onward

to

the Seventeenth

Century and

more

traveller's

tales

of

Chester...

Lucian

the

Monk | Nuns

of

St. Mary's | Chester

and

Domesday | Chester

Walls

Stroll

Introduction | Chester books on the Chester Wiki | Site Front Door | Top

of

page

|

"In whatever point of view these old ramparts are considered, they possess an imposing interest and confer incalculable benefits. To the invalid, the sedenatary student, or the man of business, occupied during the day in his shop or counting house; to the habitually indolent, who require excitement to necessary exercise, to all these, the the promenade on Chester walls have most inviting attractions, where they may breath all the salubrous winds of heaven in a morning or an evening walk.

"In whatever point of view these old ramparts are considered, they possess an imposing interest and confer incalculable benefits. To the invalid, the sedenatary student, or the man of business, occupied during the day in his shop or counting house; to the habitually indolent, who require excitement to necessary exercise, to all these, the the promenade on Chester walls have most inviting attractions, where they may breath all the salubrous winds of heaven in a morning or an evening walk.