Fifty

miles or so west of Chester along the North Welsh coast you will find the beautiful

small market town and harbour of Conwy. Fifty

miles or so west of Chester along the North Welsh coast you will find the beautiful

small market town and harbour of Conwy.

After his conquest of Wales in 1283, King Edward I set out to

hold down the country with a series of magnificent castles of which Conwy, guarding

the crossing of the river Conway, was one of the largest. Not only was there

a castle, but also a fortified town, whose the circuit of walls still survive

in their entirety.

There had been people living here long before that, of course. The pearl fishery

in the Conwy river was famous before the coming of the Legions- indeed the Roman

general Suetonius declared its acquisition to be one of his main motives for

subjugating the country around.

A shield of great value and exquisite workmanship, dedicated by Julius Caesar

to Venus Genetrix, and placed by him in her temple in Rome, was encrusted with

British pearls.

Conwy Castle, seen behind the young American visitors

in our photograph, is a masterpiece of medieval military architecture and is

associated with one of the greatest circuits of town walls to be found anywhere

in Europe- more than three quarters of a mile in length, with 22 great towers

and three original gateways.

Old illustrations show that Chester's fortified medieval gates, which were removed

in the 18th and early 19th centuries, must once have looked very like the ones which

survive here in Conwy. Most of Chester's ancient castle,

too, was swept away during the 19th century to be replaced with Thomas Harrison's Greek Revival buildings.

Conwy's walls, castle and town were, remarkably, constructed in only seven years- between

1283 and 1289- and played an important part in King Edward I's plan of surrounding

Wales in "an iron ring of castles" to subdue the rebellious population.  The

highly defensible wall Edward built around the town was intended to protect

the English colony planted at Conwy as the native population were justifiably-

and violently- opposed to the forced occupation of their homeland. The

highly defensible wall Edward built around the town was intended to protect

the English colony planted at Conwy as the native population were justifiably-

and violently- opposed to the forced occupation of their homeland.

The design and direction of the building work was undertaken by James of St. George, the greatest military architect and master mason

of his time, who was summoned from mainland Europe to implement Edward's ambitious

plans. He was born around 1230 and worked on a number of great European castles

before starting on his massive undertaking for Edward.

The beautiful Beaumaris

Castle, on the island of Anglesey was his final design in Wales and with

this he perfected his concept of the 'concentric castle'.

A town wall exists, linked to the great castle at Caernarfon, but it

is far from complete and gets lost in the modern town. By contrast, Conwy's

well-preserved wall helps the town maintain a medieval character lost by most

other Welsh castle-towns over the years.

Today, Conwy is approached from Chester and the east via the A55 road along

the North Wales coast. Approaching the town, the castle seems to suddenly rise

out of the hills. Thomas Telford's majestic old suspension bridge, connecting

the castle with the main peninsula, and depicted in many representations of

the castle over the years, has been out of use since the 1950s. A new bridge

runs parallel with the old and is the only way to enter Conwy from the east.

The magnificent castle dominates the entrance to the town, immediately conveying its sense

of strength and compactness to the observer. The eight great towers and connecting

walls are all intact, forming a rectangle as opposed to the concentric layouts

of Edward's other castles in Wales.

Almost all of the castle is accessible and well preserved. Journeying to the

top of any of the towers offers the visitor spectacular views of the town, surrounding

coastline and countryside. Sailboats and other pleasure craft dot the picturesque

harbour and quay next to the castle, while flocks of sheep may be observed everywhere on

the nearby hills.

When exploring the waterfront, pay a visit to what is allegedly

"the smallest house in Britain" or sit outside the Liverpool Arms pub, taking in the spectacle with a pint

of their excellent beer

.

Conwy Castle dominates the skyline from literally all points along

the town wall. The spur wall projecting 60 yards from the end of the quay offers

some of the best views, especially at night, when the floodlit castle is a memorable

spectacle.

Joseph Hemingway, writing in the1830s about the vanished medieval and

Roman gates of Chester, gives

the following description:

"From each side of the gates projected a propugnaculum (a wonderful word)

or bastion in order to annoy the enemy who attempted to enter; between

them, in the very entrance, was the cataract or portcullis ready

to be dropped in case they forced the gates; so that part of them might be caught

within the walls, and slaughtered, and the rest excluded. Should it happen that

the gates were set on fire, there were holes above, in order to pour down water

and extinguish the flames.

The walls were in many parts guarded by towers, the remains of which are still

visible (far better here at Conwy than at Chester) placed so as not to be beyond

bow-shot of one another, in order that the archers might reach the enemy who

attempted to gain the intervals. They were also mostly of a round form, as was

early recommended by Roman architects such as Vertruvius in order more

effectually to resist the force of battering rams".

Vertruvius' works upon military defences had been the standard reference for

hundreds of years and would have been very familiar to Conwy's builder, James

of St. George.

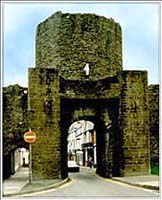

All this is easy to comprehend as one surveys Conwy's formidable towers and

gates, such as the Upper Gate, shown here.

Conwy seems like a town that time has simply chosen to pass by.

Despite the traffic and modern goods in the shops, it still looks very similar

to the town Edward envisioned some 700 years ago.

Actually, the traffic situation is much improved since a by-passing tunnel

was been built a few years ago. Formerly, the A55 main coastal route passed straight through

the town centre and was for years a notorious bottleneck.

Today, the ancient town walls, castle and simple streets thankfully continue

to offer very little to remind the visitor of the modern world.

In High

Street, you will find one of the most impressive and best-preserved Elizabethan

town houses anywhere in Britain, Plas Mawr, which was built between the years 1575

and 1585 and is open to the public.

One of the bells from the great Abbey of St. Werburgh,

(Chester Cathedral) now hangs in Conwy's little church, having been sold

by the Abbot and removed here during the frantic period of 'asset-stripping'

immediately prior to the dissolution of the monastery by the agents of Henry

VIII in 1540.

All in all, Conwy remains something of a paradox. Originally a

symbol of the English domination of Wales, in time the Welsh managed to reclaim

their town, replacing English oppression with its own medieval character. At

Conwy we get the feeling of being transported back to ancient Wales.

Despite this, it is an easy journey from Chester and is a place not to be missed

by any visitor to Britain. |

Fifty

miles or so west of Chester along the North Welsh coast you will find the beautiful

small market town and harbour of Conwy.

Fifty

miles or so west of Chester along the North Welsh coast you will find the beautiful

small market town and harbour of Conwy. The

highly defensible wall Edward built around the town was intended to protect

the English colony planted at Conwy as the native population were justifiably-

and violently- opposed to the forced occupation of their homeland.

The

highly defensible wall Edward built around the town was intended to protect

the English colony planted at Conwy as the native population were justifiably-

and violently- opposed to the forced occupation of their homeland.