he centuries-long, inexorable silting up of the River Dee, together with improvements to the navigation of the River Weaver around 1730 and the Trent and Mersey Canal Act of 1766 caused considerable concern to the merchants of Chester as they feared the town would soon be bypassed altogether in favour of the rapidly-growing city of Liverpool. he centuries-long, inexorable silting up of the River Dee, together with improvements to the navigation of the River Weaver around 1730 and the Trent and Mersey Canal Act of 1766 caused considerable concern to the merchants of Chester as they feared the town would soon be bypassed altogether in favour of the rapidly-growing city of Liverpool.

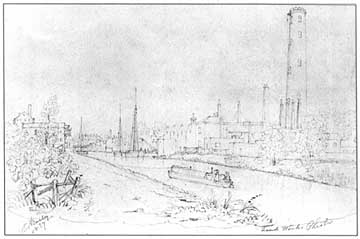

Right: This pencil drawing by Thomas Bailey shows the canal as it appeared in 1837, the Leadworks, judging from the hedgerow on the left, located in the midst of what was still a fairly rural environment. No bridge crosses the canal here at this time as City Road would not be built for another thirty years. Notice the sailing barges, versatile craft known as 'flats' which could navigate on the canals and also on the River Mersey, moored alongside the leadworks.

There soon followed a proposal to build a canal to link Chester with the new canal at Middlewich and the great canal engineer James Brindley (1716-1772) was hired to carry out surveys.

But, anxious to protect their profits, the Trent and Mersey Company and also Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater, who owned the canal named after him that connected with it, voiced their strong opposition to the new cut. Permission was nontheless granted in 1772, authorising the construction of a canal fourteen feet wide from Chester to Nantwich and Middlewich- but the vested interests had their way and it was ordered to keep at least 100 yards away from the older canal at Middlewich. As a result, plans for this section were abandoned for the next half century.

A short 'showpiece' section in Chester was completed as early as 1774. Its opening was recorded in an issue of a long-defunct local newspaper, The Chester Courant, of Tuesday, 27th December 1774 as follows: "Near Cow Lane Bridge was launched a large barge, called Egerton, 70 feet long, 14 feet wide and 70 tons burthen. Immediately after, she proceeded, full of people with french horns etc playing on board, under the walls of the city, along by the Phoenix Tower, thro' the rock that has been cut open at the Northgate, to the dam at the end of the canal now finished, being about 200 yards to the westwards of Northgate, where several cannon were fired. From thence she was conducted thro' six bridges and five locks now erected on the Christleton quarry; and afterwards was re-conducted to Cow Lane Bridge". A short 'showpiece' section in Chester was completed as early as 1774. Its opening was recorded in an issue of a long-defunct local newspaper, The Chester Courant, of Tuesday, 27th December 1774 as follows: "Near Cow Lane Bridge was launched a large barge, called Egerton, 70 feet long, 14 feet wide and 70 tons burthen. Immediately after, she proceeded, full of people with french horns etc playing on board, under the walls of the city, along by the Phoenix Tower, thro' the rock that has been cut open at the Northgate, to the dam at the end of the canal now finished, being about 200 yards to the westwards of Northgate, where several cannon were fired. From thence she was conducted thro' six bridges and five locks now erected on the Christleton quarry; and afterwards was re-conducted to Cow Lane Bridge".

Naturally, the coming of this revolutionary form of transport resulted in great changes to Chester's townscape. The origin of the deep cutting in which it runs lies with the Roman founders Deva and originally took the form of a deep defencive ditch, or fosse, excavated in the earliest days of fortress construction at the base of the natural sandstone escarpment. During the centuries of Roman occupation it would have been carefully kept clear of any debris and vegetation by which a potential enemy might gain cover or even a handhold to assist in scaling the wall but maintainance ceased with the withdrawal of the Legions, and subsequent natural erosion, as well as- in those less-than-scrupulous times- domestic waste of all kinds being disposed of by simply being thrown over the wall, over the course of centuries resulted in the fosse filling up and virtually disapearing, only reappearing when the navvies came through here in the 18th century. Today, we are so familiar with the dramatic gorge beneath our City Walls we assume it has always been that way. Such, of course, is not the case and it will be interesting for you to study our enlargements of Alexander de Lavaux's 1745 map of Chester to see how curious the area outside the North Wall and Phoenix Tower appear to our eyes before the canal was constructed.

The completed Chester-Nantwich canal opened in 1779 but, being a dead end, attracted little traffic and soon proved to be a financial disaster for its private investors. Over the next decade, there was constant talk of closure and no dividends were paid until 1813, the lifetime of the independent company.

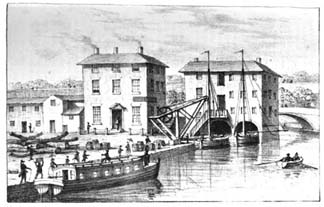

The enterprise was saved in the nick of time by the 'canal mania' of the 1790s. The Ellesmere Canal opened in 1797, linking Chester with Netherpool- later to be called Ellesmere Port. The original flight of five Northgate Locks were reduced to three and the Chester Canal caused to swing sharply in order to link with the Ellesmere at Tower Wharf (above). A new link was created to join the two canals to the River Dee via a tidal basin.

Tower Wharf developed rapidly; a dry dock for repairing canal boats was built at the junction of the two branches in 1798 and boat building facilities and warehouses soon filled the entire area. Some basins and many buildings have since disappeared but the dry dock and fine structures such as Telford's Warehouse (now beautifully restored and a popular bar/restaurant) remain with us today. Tower Wharf developed rapidly; a dry dock for repairing canal boats was built at the junction of the two branches in 1798 and boat building facilities and warehouses soon filled the entire area. Some basins and many buildings have since disappeared but the dry dock and fine structures such as Telford's Warehouse (now beautifully restored and a popular bar/restaurant) remain with us today.

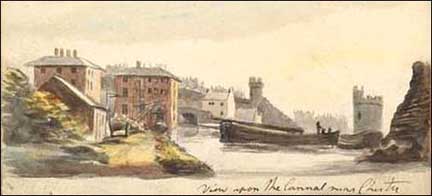

This anonymous watercolour shows the Tower Wharf area as it appeared in 1790; somewhat more rural but, on the whole, entirely familiar to modern eyes, Bonewaldesthorne's and the Watertower and Telford's Warehouse looking much as they do to us today.

This new Wirral Arm of the Ellesmere Canal proved to be a great financial success as goods could now brought straight to Chester from Liverpool and the Mersey. Major industrial developments along the canalside in Chester such as the timberyards by Cow Lane Bridge and the Leadworks (of which more below) and still-surviving Steam Mill were also made possible because of the new link.

A passenger service to Liverpool from Tower Wharf opened the same year the canal did and was very popular. You can see one of the packet boats in the illustration above. The journey took three hours and 15,000 passengers per year were using it by 1801. The service only came to an end when the Chester & Birkenhead Railway opened in 1840.

All of this greatly benefitted the debt-ridden Chester Canal Company and things improved even further when, in 1806, Chester was linked to another part of the Ellesmere now known as the Llangollen Canal- to the Denbighshire coalfields and to Whitchurch. (Earlier plans had proposed a link via Ruabon from Llangollen to Chester, but these had been abandoned). This joined the Chester Canal at Hurleston near Nantwich. Further plans for a direct canal link between Chester and Wrexham came to nothing due to costs and engineering difficulties.

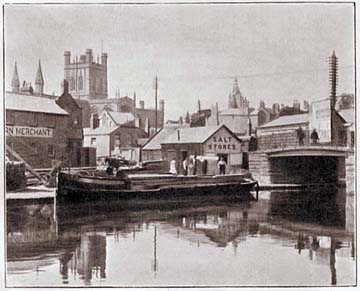

The interdependence of the Chester and Ellsmere Canal Companies led to their merger in 1813. In 1835, the Chester Canal was linked with the main canal system via the new Birmingham & Liverpool Canal at Autherley Junction near Wolverhampton. Bulk salt was brought from the Middlewich area along this canal to a wharf west of Cow Lane Bridge, a trade which, in common with those mentioned earlier, also ceased some time around 1918.

Successful as they were, the new canals proved that Chester's waterborne trade could be carried more effectively through Liverpool and the Mersey than via its own, terminally-silted port on the Dee. Industry moved to the Mersey and canal-borne trade with Chester had largely ceased by the time of the First World War. Successful as they were, the new canals proved that Chester's waterborne trade could be carried more effectively through Liverpool and the Mersey than via its own, terminally-silted port on the Dee. Industry moved to the Mersey and canal-borne trade with Chester had largely ceased by the time of the First World War.

Left: all manner of industrial premises such as salt works, corn merchants and timberyards once clustered around Cow Lane Bridge

Perceiving another growing threat, that of the new-fangled railways, the Chester & Ellesmere and the Birmingham & Liverpool canal companies united in 1845, becoming the Shropshire Union Railways and Canal Company. The new concern was immediately leased to the LNWR- the London & North Western Railway but the canal concerns continued to enjoy a great deal of autonomy and was operated vigourously as much of the network lay within the territory of the rival GWR- Great Western Railway.

The new company established its headquarters at Tower Wharf and by 1870 enjoyed a virtual trading monopoly. 252 boats were operating by 1878, many of them built at the company's yards in Chester. By 1895, there were around 400.

But the rise of the railways meant that the end was inevitable. The boatyards were sold in 1917 and, faced with escalating losses, the goods carrying operation was hastily abandoned in 1921. Small numbers of boats struggled on under new owners but the days of bulk water transport were over- in 1925 alone, 86 boats were scrapped.

The Shropshire Union Company was taken over by the LNWR in 1922 and Chester ceasing to be the company's head office. After nationalisation in 1948, most administrative duties were transferred to Northwich. In 1939, Courtauld's steam flats ceased to operate between the Mersey and Flint and trade on the Dee branch came to an end. With the exception of a few diehard private operators, commercial traffic throughout the system had largely ceased by 1957 and the canals went into what appeared to be a terminal decline until the fortuitous rise of pleasure boating. Under the care of British Waterways, which was created by the Transport Act of 1962, a vast- and ongoing- programme of restoration came about which has ensured their continuing use and growing popularity, not only with boaters but for walkers and cyclists too. The environment of our canals provide valuable wildlife havens. Once scruffy and neglected, canalsides within urban areas- certainly in Chester- are, as we shall see, now much in demand for smart residential developments.

We will meet the canal again at numerous points of our 'virtual stroll' around Chester including at the Kaleyard Gate, the North Wall and at Tower Wharf...

Above are a couple of photographs, separated by forty years, of the view from the top of the Water Tower in Boughton looking west along the Shropshire Union Canal towards Chester city centre. In the left hand picture, taken sometime in the 1950s, smoke emanating from the chimneys of the numerous industrial premises operating in the area at this time has produced a noxious smog shocking to the modern eye. The tall chimneys on the right belonged to the Chester Leadworks. These have now disappeared, with the exception of the fatter one- the 51 metre high Shot Tower- which was built in 1799 or 1800 and is now listed. It remains the tallest structure in Chester.

Many more changes have come about since the author took the photograph on the right in 1996; the large car showroom and garage on the left- 'Looker's Vauxhall'- has been replaced by apartments, as have the Leadworks buldings seen clustering beneath the Shot Tower (see below). Many more changes have come about since the author took the photograph on the right in 1996; the large car showroom and garage on the left- 'Looker's Vauxhall'- has been replaced by apartments, as have the Leadworks buldings seen clustering beneath the Shot Tower (see below).

Lead has been brought from the mines of North Wales and exported from the Port of Chester since Roman times. With the improvement in transportation brought about by the building of the Shropshire Union Canal during the 1770s, this became an ideal location for Walkers, Maltby and Company to build their new lead processing works.

A century earlier, Britiish forces had been issued with lead shot for their muskets but, because of imperfections in manufacture, much of it suffered from pockmarks on the surface, making it inefficient and even dangerous. Then, in 1782, the Bristol plumber William Watts took out a patent for his new technique, a process "for making smallshot perfectly globular in form and without dimples, notches and imperfections which other shot hereto manufactured usually have on their surface".

Watt's technique, as carried out here in Chester, was to allow molten lead- to which the deadly poison arsenic was added- to be poured from the top of the tower, passing through a griddle to separate it into tiny pellets before landing in a wooden vat of water below.

Watts perfected the technique in the tower of the beautiful St. Mary Redcliffe Church in Bristol.

The Cheshire Sheaf of May 1878 contained the following notes regarding the Lead Works from Mr Bryan Johnson of King Street, "As my father was manager of these works for many years, and as I was born in the house now occupied by byMr. A.0. Walker at the works, I maybe allowed to say a few words on the subject. My father came to Chester in the year 1800, and found the Shot Tower just commenced upon, the foundations being built, and he superintended the completion of the Shot Tower as well as the other buildings. He continued manager to Messrs. Walker, Parker, and Co., until Sir Edward Walker came to reside in Chester, about 1830. I think I have heard that when Messrs. Walker, Parker, and Co., first thought of establishing works in Chester they had almost decided upon Edgar's Field, Handbridge, as the locality; but, as the "Ellesmere and Chester Canal" was just at that time nearly ready to be opened, the present site was considered to be the best. There was, as will be remembered by some, a Shot Tower and Lead Works in Commonhall-street; but these were not, so far as I understand, so old-established as Messrs. Walker's works". The Cheshire Sheaf of May 1878 contained the following notes regarding the Lead Works from Mr Bryan Johnson of King Street, "As my father was manager of these works for many years, and as I was born in the house now occupied by byMr. A.0. Walker at the works, I maybe allowed to say a few words on the subject. My father came to Chester in the year 1800, and found the Shot Tower just commenced upon, the foundations being built, and he superintended the completion of the Shot Tower as well as the other buildings. He continued manager to Messrs. Walker, Parker, and Co., until Sir Edward Walker came to reside in Chester, about 1830. I think I have heard that when Messrs. Walker, Parker, and Co., first thought of establishing works in Chester they had almost decided upon Edgar's Field, Handbridge, as the locality; but, as the "Ellesmere and Chester Canal" was just at that time nearly ready to be opened, the present site was considered to be the best. There was, as will be remembered by some, a Shot Tower and Lead Works in Commonhall-street; but these were not, so far as I understand, so old-established as Messrs. Walker's works".

Above is a contemporary photograph of the Shot Tower, which also shows the lift shaft which was added in 1971 to make it easier for workers to reach the top- formerly they were forced to labour up an internal stone spiral staircase, which was destroyed in a fire in 1899. Its modern steel replacement seen in this view, taken from near the top of the tower's interior. (Both photographs by the author.)

This was one of only three such towers built to manufacture musket shot for the Napoleonic Wars and might, therefore, have been instrumental in the deaths of many French soldiers. The works beside the tower did, however, produce other articles beside munitions. By 1812, a rolling mill and pipe making machine had been installed and later the works produced 8 mm leadshot for adding to molten steel for the lead alloy process. Although machine-made shot became available in the 1960s, the tower shot made at Chester remained commercially viable for a few more years.

Since the demolition of a similar tower on the south bank of the River Thames in London, in preparation for the Festival of Britain in 1951, Chester's shot tower is the last remaining example in Britain. It is 168 ft high, 30 ft in diameter at the base rising to 20 ft at the top. It weighs 1,200 tons and is estimated to contain 350,000 bricks!

At the end of 2001, work ceased for good and proprietors Calder Industries prepared, after around 230 years in Chester, to move to much larger new premises on the edge of town near the Deva football stadium. We learned that the leadworks buildings- with the exception of the protected tower- were to be demolished to make way for a large new housing development by Bellway Homes. This is to comprise around 225 apartments as well as a hotel, restaurant and cafe-bar.

An archaeological evaluation of the site carried out as a result of the planned development in January 2001 revealed numerous traces of the now-demolished buildings which had been erected at the same time as the Shot Tower. These included brick walls, concrete and stone-slab flooring and pottery from vessels used in the process of extracting white lead from its ore and also for the production of small lead ingots. These specialised vessels had been produced from the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries at the Buckley potteries in North Wales. An archaeological evaluation of the site carried out as a result of the planned development in January 2001 revealed numerous traces of the now-demolished buildings which had been erected at the same time as the Shot Tower. These included brick walls, concrete and stone-slab flooring and pottery from vessels used in the process of extracting white lead from its ore and also for the production of small lead ingots. These specialised vessels had been produced from the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries at the Buckley potteries in North Wales.

Reader Allen Rimmer of Victoria, Australia kindly sent us this photograph of the Associated Lead laboratory staff taken sometime in the 1950s. He tells us, "My father has made a row by himself seated second from the front. The only other person I can identify is the Chief Chemist, Harold Slack, the gentleman with glasses, centre, back row. Michael Hoddinott (author of a history of the lead works, unpublished) was also a member of the team at this time. My father spoke of him many times but I don’t recall ever meeting him". Reader Allen Rimmer of Victoria, Australia kindly sent us this photograph of the Associated Lead laboratory staff taken sometime in the 1950s. He tells us, "My father has made a row by himself seated second from the front. The only other person I can identify is the Chief Chemist, Harold Slack, the gentleman with glasses, centre, back row. Michael Hoddinott (author of a history of the lead works, unpublished) was also a member of the team at this time. My father spoke of him many times but I don’t recall ever meeting him".

In February 2010, Ian Clough ("now living in Stourport, Worcestershire, another great canal town") wrote to tell us, "Hi, just been browsing your wonderful pages on the Chester canal and was amazed to find a photograph of the lab team from Associated Lead, back in the fifties.

I can add a couple of names for you- third from the left, back row, is Lyn Williams and fourth from the left at the back is Jim Clough, my father.

I visited the Chester canal today for the first time in nearly 50 years and despite the major developments in the area, much of it is still recognizable from my youth. Your pages have been most useful, helping me fill the many gaps in my memory".

My pleasure, Ian. Thanks for the information, both of you. Does anybody know what became of Mr Hoddinott's unpublished history? It would be an honour to reproduce it here!

In January 2003, immediately before the demolition of the leadworks commenced, developers Bellway Homes (Manchester) kindly allowed me to explore and photograph the site, including the spectacular view from the top of the Shot Tower.

There have been sightings of two different ghosts at Chester Leadworks!

The first is recorded by Michael Hoddinott in his unpublished history of the works. In the winter of 1988/9, after the works had shut for the day, the security man and his daughter spotted an old lady carrying a long, heavy bag near the paint shed. Attempting to follow the figure through the yard, they could find no trace of her. The guard later mentioned his experience to some of the older workers who, by his description, recognised a Mrs Cox, who, years before, had worked in the shot department and each day had brought cigarettes for the men in her long bag, following the same route along which she had been followed by the guard.

Then in January 2002, the local press reported that Alan Evans, the manager of a scrap metal company, while clearing a shed for demolition, spotted the figure of a man dressed in old-fashioned dark blue overalls in the corner which proceeded to walk across the room. After a crane at the back of the warehouse started operating on its own, the manager beat a hasty retreat. "I saw him in the old pipe mill, which is more than 200 years old. It would make a great movie set as it was very atmospheric. The hairs went up on the back of my neck- I knew there was somebody behind me but it was all locked up, there was no way anybody could get in. I never used to believe in ghosts, I'm not the type to even contemplate something like this.."

It seems that the overalled ghost is well known to staff at the Leadworks and been sighted many times over the years. A security guard, Evo Littler, said "I saw him at the bottom of the pipe mill, wearing a donkey jacket, pottering about. He was there for about two minutes". It seems that the overalled ghost is well known to staff at the Leadworks and been sighted many times over the years. A security guard, Evo Littler, said "I saw him at the bottom of the pipe mill, wearing a donkey jacket, pottering about. He was there for about two minutes".

One story has it that the mysterious figure was a worker who was killed on the nearby railway after leaving the pub.

Chester's oldest public clock (right), made by Whitehurst of Derby in 1803- 207 years ago, was formerly installed in the wall of one of the sheds at the Leadworks, facing out onto the canal. Unfortunately, sometime during the handover from Calder's to new owners Bellway Homes, the clock was stolen. The three-foot diameter face was removed from the wall and the works from inside the building, with no sign of a break-in, and it has been conjectured by the new owners that someone connected with the various contractors who had access to the site at the time may have been involved. They appealed for the clock's return as it was planned for it to be restored as part of the refurbishment of the historic building.

You can see a picture of it in situ in our small gallery of leadworks photographs...

But then, at the end of March, the clock was indeed, in the words of the local press, "handed back", to the reported relief of the pupils of Boughton St. Paul's Infants School, just across the canal- whose school logo features an image of the leadworks- who could see the clock from their classrooms and regarded it as "their treasure"....

Summer 2009: Sadly, and despite considerable protest, the popular Boughton St. Paul's School is no more. The school had been founded in 1830 when St. Paul's Church established on its premises a day school for the children of the parish's mill- and leadworks employees. In 1852, the Boughton Industrial School was founded on the nearby corner of Hoole Lane and Boughton as a place of refuge and education for destitute, orphaned and neglected chldren. Summer 2009: Sadly, and despite considerable protest, the popular Boughton St. Paul's School is no more. The school had been founded in 1830 when St. Paul's Church established on its premises a day school for the children of the parish's mill- and leadworks employees. In 1852, the Boughton Industrial School was founded on the nearby corner of Hoole Lane and Boughton as a place of refuge and education for destitute, orphaned and neglected chldren.

Five years later, in 1857, St. Paul's Day School moved from the church to a new home in the grounds of the Industrial School where it remained until 1941, surviving a first attempt to close it in 1908.

The school moved in 1941 to the area now occupied by the Boughton Retail Park and then for a final time in 1972/3 to a modern, single-storey building adjoining their former home, which remained in a state of dereliction for a decade until eventually being demolished to make way for a new shopping complex.

In 1983, Cheshire County Council attempted to shut the school down but this move was defeated by a brisk campaign of objection.

In 1995, a new hall was added and then, four years later, 1999, a third- again unsuccessful- attempt was made to close the school.

In December 2006, the County Council's so-called TLC ('Transforming Learning Communities') programme was launched and immediately issued the death sentence to a number of schools around the county, including Boughton St. Paul's. Once again, a well-organised and publicised campaign of objection was launched, pointing out that the school was popular- and always fully subscribed- invariably received excellent Ofstead reports and would soon be much valued by the residents of the many new apartments that had sprung up around it. As the Chairman of Governors, Susan Churchill expressed it, "For generations, Boughton St. Paul's School has been an integrated part of the community, offering not only superb education in a small, friendly environment but also providing help and encouragement to the whole family". In December 2006, the County Council's so-called TLC ('Transforming Learning Communities') programme was launched and immediately issued the death sentence to a number of schools around the county, including Boughton St. Paul's. Once again, a well-organised and publicised campaign of objection was launched, pointing out that the school was popular- and always fully subscribed- invariably received excellent Ofstead reports and would soon be much valued by the residents of the many new apartments that had sprung up around it. As the Chairman of Governors, Susan Churchill expressed it, "For generations, Boughton St. Paul's School has been an integrated part of the community, offering not only superb education in a small, friendly environment but also providing help and encouragement to the whole family".

But, when there's money to be saved and money to be made on land in an attractive location, common sense and community count for little and the end was inevitable. After 178 years of service, Boughton St. Paul's School closed its gates for the last time on Friday, July 18th 2008 and its sorrowing pupils moved to other places of education. The buildings were almost immediately demolished- vanished as if they had never been- and for the last eighteen months (as of February 2010) the site has, disgracefully, remained a derelict vacant lot. All that remains are the jolly- but now rather tragic- murals that decorate the walls of what used to be the playground...

In the Autumn of 2011, a planning application was made by the supermarket chain Waitrose for the erection of a large new store, hotel and offices on the site of both the school and the shabby Boughton Retail Park next door.

Work upon the old leadworks buildings opposite ground to a halt a couple of years ago but we hear some manner of apartment complex is earmarked for the site. Will Chester's oldest clock then be restored to its time-honoured place within the new development?

Update, September 2014: Work upon the vast new glass and steel box that will house the new supermarket is approaching completion but no progress at all has been made upon developing what is left of Chester's historic Leadworks across the canal. Watch this space.. Update, September 2014: Work upon the vast new glass and steel box that will house the new supermarket is approaching completion but no progress at all has been made upon developing what is left of Chester's historic Leadworks across the canal. Watch this space..

Returning to the the old picture at the top of the page, many of the group of buildings in the bottom right-hand corner survive today, including the lock-keeper's cottage, John Douglas' little church- which has recently been sensitively converted for residential use- and the Lock Vaults pub. The locks themselves and the bridge carrying Hoole Lane over the canal are also still very much in use.

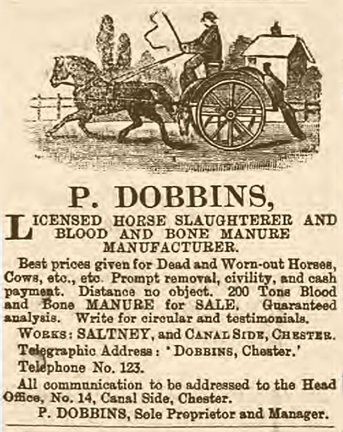

Left: the ironically-named Dobbins horse slaughterer and renderer was one of the less-than-glamourous enterprises to be found along Canal Side. The business continued to trade right into the 1990s as a scrap dealer. This advertisment was printed in the long-vanished Chester Courant in 1897.

The entire area to the right of the photograph- not to mention local house prices and road congestion- were radically transformed by the building of the Capital Bank (now Bank of Scotland) HQ and its associated huge car park. The bank is planning to embark upon further major developments between their existing buildings and the old leadworks site in the near future, as you can learn here.

In November 2003 we received some intriguing emails from Jill Statton in Sturt, South Australia, which may be summarised as follows:

"Congratulations on a great website. So much to read, I shall have to revisit soon. However, where is the info about the memorial over Euphrates' grave at the Shot Tower, Chester Leadworks? Did I miss this in my haste? If not already included, perhaps you might consider adding it to your site?

My interest in Euphrates- John Mytton's (of whom more below) beloved horse- is that my ancestor, William Webb, painted Euphrates and exhibited the painting at the Royal Academy in 1825. William is the subject of a book I am writing on the family. Hence I would love a photo of the memorial or some further information about it. Has it been moved? or is it still there- where?

My information for Euphrates came from Judy Egerton's book, "British sporting and animal paintings 1655-1867" (London, 1978). In it she states (page 235):

“Euphrates, a chestnut colt by Quiz out of Persepolis, was bred by Lord Rous and foaled in 1816. He won numerous races and, after several changes of ownership, was purchased by John Mytton, squire of Halston near Shrewsbury, a famous and eccentric sportsman, for whom he continued to win trophies, including the Gold Cup at Lichfield in 1825- a victory commemorated in this painting [by my ancestor, William Webb]. He continued to race until he was thirteen years old. By then Mytton was heavily in debt... everything was sold except Euphrates. Mytton entrusted him to a friend, requesting that the horse should be shot rather than end his career by being "put to the drudgery of drawing a coach, or any other ignoble purpose". He was duly shot in June 1832 and a memorial over his grave near the Shot Tower at Chester Lead Works commemorates his achievements". “Euphrates, a chestnut colt by Quiz out of Persepolis, was bred by Lord Rous and foaled in 1816. He won numerous races and, after several changes of ownership, was purchased by John Mytton, squire of Halston near Shrewsbury, a famous and eccentric sportsman, for whom he continued to win trophies, including the Gold Cup at Lichfield in 1825- a victory commemorated in this painting [by my ancestor, William Webb]. He continued to race until he was thirteen years old. By then Mytton was heavily in debt... everything was sold except Euphrates. Mytton entrusted him to a friend, requesting that the horse should be shot rather than end his career by being "put to the drudgery of drawing a coach, or any other ignoble purpose". He was duly shot in June 1832 and a memorial over his grave near the Shot Tower at Chester Lead Works commemorates his achievements".

I searched the net for references to Chester Leadworks and came upon your site. I did wonder about Chester, but assumed that the Mytton family had some connection with the Leadworks. He came from Halston, Shropshire- not far down the road as the crow flies, at least to we in Oz.

Perhaps Lord Rous was from Chester? Are there any old famous studs or racing stables nearby? Further clues to his connection with Chester may be the jockey, Thomas Whitehurst, and trainer, W. Dilly.

Hope this helps- there must be a clue here somewhere as to why Chester.”

A little about ‘Mad Jack’ Mytton...

John "Jack" Mytton was born 1796 to a family of Shropshire squires. Many of his ancestors had been in the parliament and John Mytton served in the Hussars. From his father he inherited a family seat at Halston Hall near Shrewsbury, £60.000 and annual income of £10,000.

Mytton would go hunting in any kind of weather. His usual winter gear was light jacket, thin shoes, linen rousers and silk stockings- but in the thrill of the chase he could strip down and continue the chase naked. He also had numerous pets in his manor.

Another thrill for him was reckless driving of carriages. He could drive his gig at high speed in an obstacle like a rabbit hole only to see if it would turn over. Once he tested if a horse pulling a carriage could jump over a tollgate . It could not. He managed to survive these self-made accidents without serious injuries.

Contemporary society considered his behavior scandalous. He once picked a fight with a miner who disturbed his hunt and lasted 20 rounds before the miner gave up. He once arrived in a dinner party riding a bear and when he tried to make it go faster, the beast bit into his calf. Contemporary society considered his behavior scandalous. He once picked a fight with a miner who disturbed his hunt and lasted 20 rounds before the miner gave up. He once arrived in a dinner party riding a bear and when he tried to make it go faster, the beast bit into his calf.

Mytton was also a drinking man and could drink eight bottles of port wine a day with a helping of brandy . He managed to kill one of his horses, Sportsman, by making it drink a bottle of port.

Mytton was spendthrift and cared little about warnings that his money was running out. He could drop bank notes in his estate and gave his servants lots of spending money. Once he lost his racetrack winnings- several thousand- in Doncaster races when the wind blew them off.

Left: the new apartments that have recently risen on the site of the old Chester Leadworks

His workmen and tenants regarded him as a generous man. Over fifteen years he managed to spend his inheritance and then fell into deep debt. In 1830 he fled to France to avoid his creditors. During his stay he tried to cure his hiccups by setting his shirt in fire. It apparently did work but only the intervention of his friends spared him of more serious injuries.

After couple of years he decided to return to England and ended up in debtor's prison. He died there in 1834.

We’ve talked to the local record office, a city council archaeologist, a member of the company responsible for the archaeological watching brief on the site and a clutch of local historians- without a result. Nobody has a clue. If you have any ideas regarding the puzzle of Euphrate’s grave at the Shot Tower, both Jill (jill_statton@yahoo.com.au) and ourselves would love to know!You can learn a little of yet another local curiousity involving a dead horse- the once-famous 'skelly 'orse' in Princess Street- here...

Now go on to part II of our exploration of the Chester Canal..

Old

Pics of Liverpool & Chester | Chester Gallery | B&W Picture Place | Site

Front Door | Site Index | Contact us

Canal Area 2 | 3 | Chester Leadworks pictures | Chester Canal gallery | Chester's canal & boatyard on the Chester Wiki

|