If you think our Virtual Stroll is entertaining, that's nothing compared to our real guided walks!

Join us to explore the world famous walls- the most complete in Britain- and discover the rest of our lovely city as well. Quick introductory tours of the city centre or lengthy and detailed study walks upon specific themes, the choice is yours. Available all year round, reasonably priced, friendly, informal and very informative- click on the picture for more details...

|

Chester:

A

Virtual

Stroll

Around

the

Walls

Melkin's Prophecy III

by Steve Goodwin

On to Chapters 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Bibliography | Back to Chapter 1 | 2

he relevant section of Geoffrey’s text that is of interest states that, after Arthur’s final battle, his mortally wounded body was transported to Avalon where he was later buried. The Avalon equals Glastonbury myth can be traced back to the 1190’s when the monks of Glastonbury announced that remains of Arthur were discovered in the abbey’s grounds. This fabricated discovery is best understood when viewed as monastic propaganda intended to boost their prestige at a time before their later wealth and power was obtained. Essentially, monasteries and Abbey’s were the theme parks of their day. Put simply – the more venerated the relic, the more visitors, the more revenue, and so on. This is a highly simplified explanation and further evidence will be presented as the story proceeds.

he relevant section of Geoffrey’s text that is of interest states that, after Arthur’s final battle, his mortally wounded body was transported to Avalon where he was later buried. The Avalon equals Glastonbury myth can be traced back to the 1190’s when the monks of Glastonbury announced that remains of Arthur were discovered in the abbey’s grounds. This fabricated discovery is best understood when viewed as monastic propaganda intended to boost their prestige at a time before their later wealth and power was obtained. Essentially, monasteries and Abbey’s were the theme parks of their day. Put simply – the more venerated the relic, the more visitors, the more revenue, and so on. This is a highly simplified explanation and further evidence will be presented as the story proceeds.

So if we accept that the link between Avalon and Glastonbury is at best weak. Where else could Avalon be? As mentioned earlier there is an Avalon tradition in North East Wales. Our first source is a little known 13th century manuscript called Vera Historia De Morte Arthuri or The True History of the Death of Arthur. The text was only published in the early 20th century after spending centuries in the care of the Franciscan monks of Chester. It is said that the manuscript was given over from a Cistercian monastery in North Wales about the time of the Reformation. It has been suggested that the Vera was written to counter the claims made in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s version of events, however, they both may have originated from a common source written in the ‘British tongue’ or oral traditions. Again, the interesting elements in both accounts follow Arthur’s final battle. The Vera states that:

So if we accept that the link between Avalon and Glastonbury is at best weak. Where else could Avalon be? As mentioned earlier there is an Avalon tradition in North East Wales. Our first source is a little known 13th century manuscript called Vera Historia De Morte Arthuri or The True History of the Death of Arthur. The text was only published in the early 20th century after spending centuries in the care of the Franciscan monks of Chester. It is said that the manuscript was given over from a Cistercian monastery in North Wales about the time of the Reformation. It has been suggested that the Vera was written to counter the claims made in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s version of events, however, they both may have originated from a common source written in the ‘British tongue’ or oral traditions. Again, the interesting elements in both accounts follow Arthur’s final battle. The Vera states that:

“At length the King, slightly restored by an improvement in his condition, gives orders to be taken to Gwynedd, since he had decided to sojourn in the delightful Isle of Avallon because of the beauty of the place”. (Carley; 2001; p.137)

Here again we have the setting of Gwynedd which in the 6th century encompassed most of North Wales. Now, Geoffrey opens his account by stating that his source was a book written in the ‘British tongue’, which would make Avalon – Afallach/Aballac (see Bartrum 1993) Afallach is also mentioned in the Welsh Triads, these are bardic stanzas on many ancient themes which are presented in groups of three. “The number three was conspicuous in Celtic thinking – it survived, notably, in the Welsh summaries of bardic tradition known as triads” (Ashe;1990;p.117). Below is the triad that mentions Afallach:

“The Three Perpetual Harmonies of the Island of Britain:

One was at the island of Afallach

And the second at Caer Caradawg

And the third at Bangor.

In each of these three places there were 2400

Religious men; and of these 100 in turn continued

Each hour of the twenty-four hours of the day and

Night in prayer and service to God,

Ceaselessly and without rest forever.”

(Bromwich.R; 1979; p. 57)

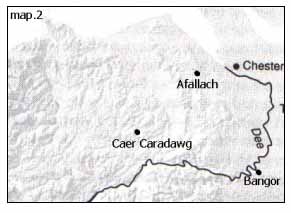

The Three Perpetual Harmonies (see Blake & Lloyd; 2000; p.127) are generally thought to equate as follows: Afallach = Glastonbury, Bangor = Bangor on Dee, and Caer Caradawg = Salisbury. However, as Blake and Lloyd point out, when we look at the map of North-east Wales, the region formerly known as Clwyd (see map.2) we find an Afallach, a Bangor and a Caer Caradawg. Furthermore, all three are also located within the new bishopric renamed by Geoffrey of Monmouth/Bishop of St. Asaph.

Afallach is the parish now known as Rhosesmor in Flintshire. The township held

Afallach is the parish now known as Rhosesmor in Flintshire. The township held

the name Afallach until the late 19th century and the name can be traced back in local documents to 1304. Tradition states that the site owes its name to the Iron-age ring-fort that dominates the area. In Ellis’ (1956) Flintshire Place-names we find Caer Fallwch and he states “Fallwch is probably Afallach, Afallwch (Aballac) of the Triads.” Caer is Welsh for ‘fort’. So therefore we have the ‘Fort of Afallach’.

I could find three plausible origins for the term Afallach. The first is Afallach as a name or title, the second has at its root the Isle of Apples and the third is that it derives from a Hebrew title for a community leader – Alabarch. Of the three, the title/name explanation seems most plausible as Afallach can be traced to the genealogies of the royal houses of Wales. In the elaborate family trees of both Gwynedd and Powys we find at the very top of both genealogies Afallach ap Beli (Afallach son of Beli). These are both classed as divine ancestors of the noble royal families, just as the Saxon kings traced their lineage back to Woden and the sort. Bartrum’s Welsh Classical Dictionary points out that Ynys (Isle) Afallach was named after a curtain figure called Afallach which evolved later into the Avalon first used by Geoffrey of Monmouth and in the subsequent romances. The Ynys or Isle element is a commonly used title in Wales often used to denote an island or a raised area of land surrounded a river or marsh. A good example of an inland isle is found in the Clwyd valley called Llanynys, where the village sits within a fork on the river Clwyd. Other examples of this Welsh form of the inland isle are; Ynyshir, Ynysborth, Ynysddu, Ynystawe and Ynysybwl. For now we shall leave Afallach. However, it is worth noting that a monastery site can still be identified and is linked to a church site that bares the name of a saintly daughter Maelgwyn Gwynedd.

Bangor or Bangor-on-Dee is approximately 15 miles south-east of Afallach.

Hywel Wyn Owen’s – The Place-names of Wales; states that Bangor means ‘a wattled fence’ in general, and ‘the plaited cross-bar strengthening the top of a wattled fence’ in particular. Whereas Afallach’s early history is shrouded in darkness, Bede and others describe the Celtic monastery of Bangor in detail. Bede (731 AD) describes a large monastic site encircled by a wattle fence, and the site housed several thousand monks similar to the account in the Triads. Tradition states that it was here that the monk Pelagius was educated and formulated his controversial and popular interpretation of Gnostic Christianity (more later). And here also that Augustine, sent by the Pope in 597, met with the Celtic Christians leaders to persuade them to follow Roman religious practices. It would appear that the Celtic church evolved independently from that of Rome and Augustine hoped to change what he thought were heretical practices within the Celtic tradition. Many have commented that the native church had more in-common with the Christians of the eastern Mediterranean than with that of Rome. However, Augustine’s offer was rejected and by chance the monastic city of Bangor was destroyed and the monks were massacred. We will never know how much influence Augustine had over this final action, but it is worth noting that over a century later this is still an emotive issue. Bede, a monk of the then Anglo-Roman church states that the massacre of unarmed monks was divine retribution for rejecting Augustine’s offer. Finally it is interesting that Blake & Lloyd (2000) point out that both St. Hilary (c.AD 300-367) and St. Benedict (c.AD 480-544) considered Bangor to be ‘mother of all monasteries’.

The 3rd Perpetual Harmony was Caer Caradawg/Caradoc which is the name of ancient circular hill fort high above Cerrydrudion (Stones of the heroes), Denbighshire. The area (see map 2) is linked to a now lost monastic site and Blake & Lloyd suggest that this was the site of the “massacre of the nobles” where the Saxons murdered the leaders of the Britons. For more on this site see Blake & Lloyd’s page 127.

The 3rd Perpetual Harmony was Caer Caradawg/Caradoc which is the name of ancient circular hill fort high above Cerrydrudion (Stones of the heroes), Denbighshire. The area (see map 2) is linked to a now lost monastic site and Blake & Lloyd suggest that this was the site of the “massacre of the nobles” where the Saxons murdered the leaders of the Britons. For more on this site see Blake & Lloyd’s page 127.

To re-cap: A key player in the embellishment and re-working of ancient bardic stories of Arthur and Avalon was Geoffrey of Monmouth. Geoffrey’s reward was to be made bishop of the new bishopric of St. Asaph, the region where we can find traces of the original Avalon. Furthermore the independent interpretation of the death of Arthur (Vera) states that Afallach/Avalon was located in North Wales. We now have a credible alternative for the original site of Afallach or Avalon. As one of the 3 perpetual harmonies the village/township of Caer Afallach existed on the map until 1890’s.

The prophecy continues;

“with avidity claims the death of pagans

More than all in the world beside”

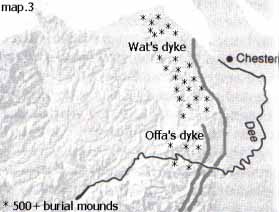

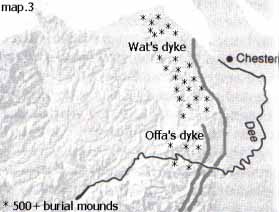

The text here appears to suggest that Avalon/Afallach was once a pagan burial site. This concurs with the area around Caer Afallach which is now known as Rhosesmor. The hills of Flintshire are peppered with hundreds of ancient burial mounds. Within one such mound the Golden Cape was discovered in the 1830’s. This is currently kept at the British Museum and has been classed as one of the top 10 treasures found in Britain. It was discovered in the market town of Mold, known in Welsh as Yr Wyddgrug or the ‘mound of the grave’. Mold is about 3 miles south of the Afallach site and there are few places in Britain where the concentration of ancient pagan burial mounds is greater.

The next line continues;

“For the entombment of them all”.

This line brings to mind a strange account written in the mid 6th century by the Byzantine historian and chronicler Procopious. In his account ‘The Gothic War’, Procopious claims that in Britain there was an ancient wall where things on each side of it were very different. This is often equated with Hadrian’s Wall on the Scottish borders. Yet, Procopious clearly states that the wall had an east-side and a west-side, however, Hadrian’s Wall run east-west and therefore has a north and a south side. Procopious also states that Britain had a reputation throughout Europe as the gateway to the ‘Otherworld’. In Procopious’ words:

“As I have arrived at this point of my history, it is incumbent on me to record a tradition very nearly allied to fable, which has never appeared to me true in all respect, though constantly spread abroad by men without number, who assert that themselves have been agents in the transactions, and also hears of the words. I must not, however, pass it by altogether unnoticed, lest when thus writing concerning the island of Brittia (Celtic Britain) I should bring upon myself an imputation of ignorance of circumstances perpetually happening there. They say, then, that the souls of men departed are always conducted to this place.”(Skene; 1868; p.202-3)

Procopious appears uncertain about what he records. Whilst dismissing the well known tradition as mere ‘fable’, he also adds that the tradition ‘never appeared to me true in all respects’. Like much of this material the central theme relies on what people believed to be true many centuries ago and beliefs are difficult to corroborate. So apart from the ancient wall that runs in a north-south orientation, Procopious adds that the souls of the dead are always conducted to an undisclosed location in Britain. Now I am not arguing that Procopious is definitely describing exactly the same as the prophecy, however, there are many similarities that may point to common origin that was ancient by the time Procopious was writing.

Procopious appears uncertain about what he records. Whilst dismissing the well known tradition as mere ‘fable’, he also adds that the tradition ‘never appeared to me true in all respects’. Like much of this material the central theme relies on what people believed to be true many centuries ago and beliefs are difficult to corroborate. So apart from the ancient wall that runs in a north-south orientation, Procopious adds that the souls of the dead are always conducted to an undisclosed location in Britain. Now I am not arguing that Procopious is definitely describing exactly the same as the prophecy, however, there are many similarities that may point to common origin that was ancient by the time Procopious was writing.

As mentioned earlier, scholars have regarded Procopious’ wall as equating to Hadrian’s Wall of northern Britain. However, as we have seen the account does not fit that of the Scottish borders. Yet the account begins to make sense when applied to the 37 mile linear earthwork known as Wats Dyke in North Wales. The dyke is generally regarded as being of Mercian construction from the 8th century, but there is good evidence to suggest that it was actually constructed many centuries earlier. A recent archaeological dig and radio-carbon dating suggests that a more likely date of late 4th /early 5th Century which corresponds to the final years of Roman Britain (see History Today; Aug.1999). If we now look at map 3 the dyke/wall follows a north – south orientation and all the burial mounds are on the west side as in Procopious’ account.

To re-cap, both the Prophecy and Procopious describe a place of pagan burial where the souls of the dead are “always conducted” which is very similar to “for the entombment of them all”. The geography for this mysterious place corresponds Wats Dyke in N. E Wales.

On to part IV

Site Front Door | Site Index | Chester:

A Virtual Stroll Around the Walls

The Black & White Picture Place | Readers Letters | Links

he relevant section of Geoffrey’s text that is of interest states that, after Arthur’s final battle, his mortally wounded body was transported to Avalon where he was later buried. The Avalon equals Glastonbury myth can be traced back to the 1190’s when the monks of Glastonbury announced that remains of Arthur were discovered in the abbey’s grounds. This fabricated discovery is best understood when viewed as monastic propaganda intended to boost their prestige at a time before their later wealth and power was obtained. Essentially, monasteries and Abbey’s were the theme parks of their day. Put simply – the more venerated the relic, the more visitors, the more revenue, and so on. This is a highly simplified explanation and further evidence will be presented as the story proceeds.

he relevant section of Geoffrey’s text that is of interest states that, after Arthur’s final battle, his mortally wounded body was transported to Avalon where he was later buried. The Avalon equals Glastonbury myth can be traced back to the 1190’s when the monks of Glastonbury announced that remains of Arthur were discovered in the abbey’s grounds. This fabricated discovery is best understood when viewed as monastic propaganda intended to boost their prestige at a time before their later wealth and power was obtained. Essentially, monasteries and Abbey’s were the theme parks of their day. Put simply – the more venerated the relic, the more visitors, the more revenue, and so on. This is a highly simplified explanation and further evidence will be presented as the story proceeds. So if we accept that the link between Avalon and Glastonbury is at best weak. Where else could Avalon be? As mentioned earlier there is an Avalon tradition in North East Wales. Our first source is a little known 13th century manuscript called Vera Historia De Morte Arthuri or The True History of the Death of Arthur. The text was only published in the early 20th century after spending centuries in the care of the Franciscan monks of Chester. It is said that the manuscript was given over from a Cistercian monastery in North Wales about the time of the Reformation. It has been suggested that the Vera was written to counter the claims made in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s version of events, however, they both may have originated from a common source written in the ‘British tongue’ or oral traditions. Again, the interesting elements in both accounts follow Arthur’s final battle. The Vera states that:

So if we accept that the link between Avalon and Glastonbury is at best weak. Where else could Avalon be? As mentioned earlier there is an Avalon tradition in North East Wales. Our first source is a little known 13th century manuscript called Vera Historia De Morte Arthuri or The True History of the Death of Arthur. The text was only published in the early 20th century after spending centuries in the care of the Franciscan monks of Chester. It is said that the manuscript was given over from a Cistercian monastery in North Wales about the time of the Reformation. It has been suggested that the Vera was written to counter the claims made in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s version of events, however, they both may have originated from a common source written in the ‘British tongue’ or oral traditions. Again, the interesting elements in both accounts follow Arthur’s final battle. The Vera states that:  Afallach is the parish now known as Rhosesmor in Flintshire. The township held

Afallach is the parish now known as Rhosesmor in Flintshire. The township held The 3rd Perpetual Harmony was Caer Caradawg/Caradoc which is the name of ancient circular hill fort high above Cerrydrudion (Stones of the heroes), Denbighshire. The area (see map 2) is linked to a now lost monastic site and Blake & Lloyd suggest that this was the site of the “massacre of the nobles” where the Saxons murdered the leaders of the Britons. For more on this site see Blake & Lloyd’s page 127.

The 3rd Perpetual Harmony was Caer Caradawg/Caradoc which is the name of ancient circular hill fort high above Cerrydrudion (Stones of the heroes), Denbighshire. The area (see map 2) is linked to a now lost monastic site and Blake & Lloyd suggest that this was the site of the “massacre of the nobles” where the Saxons murdered the leaders of the Britons. For more on this site see Blake & Lloyd’s page 127. Procopious appears uncertain about what he records. Whilst dismissing the well known tradition as mere ‘fable’, he also adds that the tradition ‘never appeared to me true in all respects’. Like much of this material the central theme relies on what people believed to be true many centuries ago and beliefs are difficult to corroborate. So apart from the ancient wall that runs in a north-south orientation, Procopious adds that the souls of the dead are always conducted to an undisclosed location in Britain. Now I am not arguing that Procopious is definitely describing exactly the same as the prophecy, however, there are many similarities that may point to common origin that was ancient by the time Procopious was writing.

Procopious appears uncertain about what he records. Whilst dismissing the well known tradition as mere ‘fable’, he also adds that the tradition ‘never appeared to me true in all respects’. Like much of this material the central theme relies on what people believed to be true many centuries ago and beliefs are difficult to corroborate. So apart from the ancient wall that runs in a north-south orientation, Procopious adds that the souls of the dead are always conducted to an undisclosed location in Britain. Now I am not arguing that Procopious is definitely describing exactly the same as the prophecy, however, there are many similarities that may point to common origin that was ancient by the time Procopious was writing.