here

must be many Cestrians, and thousands of others further afield, who will be

deeply dismayed by the recent announcement that David McLean is to implement

his planning permission for a new office block at the rear of Dee House.

here

must be many Cestrians, and thousands of others further afield, who will be

deeply dismayed by the recent announcement that David McLean is to implement

his planning permission for a new office block at the rear of Dee House.

Dismayed but hardly surprised that, once again, the avarice of a property developer

coupled with the complacency and complicity of the City Council and the arrogance

of English Heritage have conspired to deny the people of Chester, and its many

visitors, the all too rare opportunity these days to witness the uncovering

and restoration of one of its few remaining major archaeological treasures-

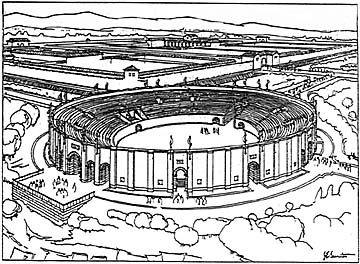

the amphitheatre of the Roman legionary fortress of Deva.

This part of the city is so rich in heritage remains and leisure facilities-

St. John's Church, the Walls, the south-east angle tower of the legionary fortress,

the Roman Gardens, the Groves amd Grosvenor Park- that it practically constitutes

a cultural zone or antiquities park yet the council is promoting the growth

of a commercial canker at its heart.

I suppose this should hardly come as a surprise for the council is merely continuing

its long tradition of archaeological vandalism. True, it nowadays fulfils its

obligations under planning law to archaeological remains by ensuring they are

either recorded before being destroyed to make way for development or left untouched

in the ground, but when it comes down to treating them imaginatively or ensuring

public access the city council has always lacked vision and ambition. Given

what other places with a far more modest archaeological inheritance have managed

to do, Chester's achievements in this direction are positively Lilliputian.

One must assume that familiarity breeds contempt. This is the authority that

allowed the destruction of the Elliptical Building- an extraordinary

and fascinating Roman building without parallel anywhere in the Roman World-

in the late 1960s together with the well-preserved remains of an adjacent bath-building

with walls still standing 10 feet high. And what new building was so important

as to justify this destruction? None other than the new council offices with

their accompanying underground car-park named, both erroneously and insultingly,

as the Forum. All that is left to see is a minute and neglected portion

of the neighbouring Headquarters Building.

It is both ironic and depressing that the city has lost so many of its archaeological

treasures, with little or no record, in order to accommodate the motor-car when

as little as 20 years later the authorities are trying to keep them out of the

city-centre.

Chester suffered an even greater loss a few years earlier in 1964 when the impressive

ruins of the main bath-building of the fortress- which included enormous rooms

40 feet wide and 70 feet long containing mosaic floors, complete underfloor

heating systems, bathing pools, and enclosed by walls 4 feet thick and 12 feet

high- were bulldozed aside to enable the construction of the Grosvenor Precinct;

it is true, as it says in the recent television advertisement, that the precinct

is "surrounded by history" but it certainly doesn't have any beneath it any

more. Preserving and placing on display any one of these buildings would have

made Chester a centre of excellence in the heritage field and miles ahead of

York.

Today the council spouts impressive sounding policies in its jargon-laden "mission

statement" and produces numerous feasibility studies but, as is so often the

case these days, there is much gloss and little substance. The city trades on

its Roman heritage but does surprisingly little to protect and enhance it. Instead,

it rests on its laurels and exploits and takes credit for the past work of others,

doing just enough to maintain its historic heritage but showing little sign

of understanding its real worth or what, if imaginatively managed, it could

contribute to the economic as well as the cultural life of the city.

The vision of those who control the authority rarely lifts above the horizon

of their expense and allowance claims or exploiting those short term populist

causes for their own self-interest. With very few exceptions the "heritage assets"-

to use an ugly but handy phrase- of Chester were preserved or established by

individuals and independent bodies. The Grosvenor Museum was built by public

donations raised chiefly by the Chester Archaeological Society and that

organisation was also responsible for recovering the internationally important

collection of Roman inscriptions, sculptures and fragments of architecture which

it houses together with many thousands of other artefacts.

There used to be a strong partnership between the council and such voluntary

sector bodies but that relationship appears to have been devalued and discarded

by the council in recent years. Having (ostensibly at least) taken on board

the concerns and some of the functions of such groups the council seems to feel

that it can now ignore them and their views with impunity. It, or rather the

councillors and the highly salaried chief officers, have become arrogant to

the extent that they are convinced they know best and if they can't make a project

work they'll make damned sure that no-one else can. Yes they can plead constraints

by central government on expenditure but that is no excuse for preventing others

from trying to succeed where they have failed. They regard themselves as "professionals"

and all others as "amateurs" but they would do well to remember the real meaning

of those two terms. Not really interested or caring, and with only a shallow

understanding themselves, these people ridicule those with a deeper knowledge

as "elitists" or "academics". They are truly at home in the current age of the

'barbarian manager'.

To return to the case of the amphitheatre. The history of the discovery and

management of this monument well illustrates many of above points. It was discovered

in 1929 by the Chester Archaeological Society which paid for excavations to

determine its exact position and outline. At this time, a scheme for the straightening

out of Little St John Street was being planned by the council with the diverted

road planned to run right across the amphitheatre. The Society lobbied not only

the council but also the government and launched a national appeal for funds

to purchase the strategically placed St John's House and its grounds so that

the remains could be protected and eventually excavated and displayed. A tremendous

success, gaining even the support of the-then prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald,

the council was shamed into postponing the road scheme. The money raised by

the Society enabled them to buy the property and, after the interruption of

the Second World War and its aftermath, they came to an agreement with the Ministry

of Public Building and Works, later the Department of.the Environment, whereby

the property was donated to the nation so that the northern half of the amphitheatre

could be excavated and placed on public display. The Society not only gifted

the site to the government but also paid for the costs of demolishing St John's

House and even donated more than £5,000 to the costs of excavation and conservation;

a tidy sum at 1960s prices. Perhaps as a sign of things to come, when the monument

was opened to the public in 1972 the Society's instrumental role was overlooked

and is entirely without mention on the information panels or the site.

It was only two years later that the first opportunity to achieve the exposure

of the rest of the amphitheatre presented itself when the Ursuline Convent then

occupying Dee House placed it on the open market. Neither local nor central

government seized the opportunity and Dee House was sold to British Telecom.

It came onto the market again in the mid-1980s and a local businessman, Tony

Barbet, negotiated an option to purchase the site, hoping to realise his

ambition not only to expose the other half of the amphitheatre but also to build

a new museum and visitor centre at the south end of the site which could tell

far more of the story of Roman Chester than current facilities allowed.

Mr Barbet could have handled the publicity more sensitively for his scheme was

criticised for being disney-esque and hardly worth the loss of the by now listed

(but only with Grade II unstarred status) Dee House. The local branch of the Civic Trust and the national period societies objected vehemently and

vociferously. Some in the council were also upset, seeing the scheme as a threat

to the city's museum services. Yet, after years of discussion and having to

undergo the rigours and costs of a public inquiry, Barbet won the day and was

granted permission for his scheme, including the demolition of Dee House, in

1990. By then though his expenditure had become too great to bear and he was

ruined financially.

A few years later and the site was up for sale again. One might have thought

that by now English Heritage, given that the DoE had spent so much on uncovering

one half of the amphitheatre, would have stepped in and purchased the remainder

for the nation. But no, in what to many must have seemed a betrayal of the hard

work and aspirations of local people as well as the principles of the DoE in

earlier times, they stood aloof and allowed the site to be bought by the property

developer David MacLean who 'generously' allowed the city council to

buy the older part of Dee House and some of its grounds.

By now, English Heritage had adopted its "leave it undisturbed if at

all possible" policy even in cases such as this where half of the monument had

already been excavated by their predecesor organisation. A need to avoid

expenditure rather than the oft-quoted concern to await improvements in investigative

techniques was the real motive for this policy. It is a further irony that

the general public was denied access to its archaeological heritage in past

decades because it was destroyed, often even without record, and now the same

is happening because government policy says leave it untouched (though not necessarily

unaffected) by development. The council obviously had no idea of how to take

the project forward, they were merely displaying their usual dog-in-the-manger

attitude of being afraid of anyone else stepping in and taking up the existing

planning permission and thus creating a facility which would put their own museum

service in the shade.

Much publicity surrounded the council's purchase and it was announced that Dee

House would be retained and used as a heritage interpretation centre, the Civic

Trust and allied bodies being relieved at its retention, with some promised

improvements to the exposed part of the amphitheatre. This appeared to put an

end to any hopes of exposing the entire amphitheatre and David McLean's reward

was planning permission to demolish the 1930s extension at the rear of Dee House

and put a new office block in its place. English Heritage raised no objections

to this scheme and so effectively cut the legs from under those who still believed

in the attainment of a complete amphitheatre.

To take their scheme forward, the council set up a charitable trust, the Chester

Heritage Trust - whose membership consisted of city councillors, members

of the Civic Trust, and other local 'worthies' including the usual ego-tripping

architect but, astonishingly, not a single archaeologist, let alone a representative

from the Archaeological Society. In view of subsequent events, they may be thankful

they were not associated with it. Four years on and what has that body achieved?

First, it attempted unsuccessfully to get a grant from the Heritage Lottery

Fund for the costs of a feasibility study of the refurbishment of Dee House.

Then, it came up with the idea of persuading McLean to abandon his scheme and

build a hotel instead, at the same time demolishing Dee House and excavating

the southern half of the amphitheatre. This was actually supported by those

same members of the Civic Trust who only a few years earlier when Barbet attempted

to do this had supposedly been outraged at the idea. The words hypocrisy and volte face spring to mind.

Anyway, in this they also failed, apparently lacking any idea how to mount a

campaign to raise the necessary funds. Now we are in the situation where McLean

intends to implement his planning permission and erect a new building which

will hinder, but not actually prevent, the exposure of the rest of the amphitheatre.

At the same time, because of all this prevarication the deterioration of Dee

House has reached a very serious state despite it being owned by the city council.

Perhaps they will have the courage to demolish it and pursue the full exposure

of the amphitheatre as a long term goal, something which is their stated aim

in the Council minutes. Don't hold your breath though, because we now hear from

the city's Chief planning officer, Andrew Farrall, that talks are underway

to convert Dee House to mixed heritage/commercial use; perhaps moving Chester

Visitor Centre to the ground floor with commercial offices above. The organisation

with which these talks are being held is no doubt David McLean Developments.

We are told that the firm is "reluctant to link its (Dee House's) future with

work on the new county court building". However, the game is given away by the

next sentence of the statement by Mark Thomas, the company's development

director, who said "The building due to start next month is stage one of our

plans".

Mr Farrall sees this as a "win, win, win situation". No Mr Farrall! It is perfectly

clear to all those who are not obsessed solely with economic development at

any cost that if it goes ahead this will be a "lose, lose, lose situation".

The condition of Dee House is now such that it is very doubtful if any of its

historic interior, or the few features which survived BT's occupancy of the

building, can be salvaged. Indeed, I would not be at all surprised if the 'refurbishment'

being concocted by Mr Farrall and his co-conspirators at McLean's entails the

preservation merely of the building's facade with the remainder demolished and

rebuilt.

And as to the possibility of money being available from the commercial rents

obtained to pay for further excavation of the aniphitheatre, this is meaningless

as the very retention of Dee House and the space needed for access precludes

the investigation of all but a tiny section of the Roman structure; sufficient

for a 'kiddies-corner dig' but little else. So, those who wanted to see Dee

House preserved intact will lose; those who wanted to see the investigation

and exposure of the entire amphitheatre will lose; those who wanted to

see a new Roman museum on the site where more of the city's magnificent collections

could be displayed rather than packed away in a warehouse will lose;

the city itself will lose because it will have given away what is probably the

last of many opportunities it has had to be an international centre of archaeological

excellence befitting its status as one of the most important sites of Roman

Britain.

David McLean, too, will lose in the long term because he will be throwing away

the opportunity to act imaginatively and with public spiritedness to develop

the site along the lines I have described and, by using his commercial shrewdness

(just think of the popularity of the "Time Team" and similar television programmes,

Mr McLean)- guarantee its future success and himself a place in the pantheon

of local benefactors for as long as Chester exists.

Only those uncultured barbarians who pursue short-term gain or who prefer

heritage trivia over quality education facilities will stand to gain.

So rise to the occasion David McLean, English Heritage and the City Council!

Put this scheme on hold, think again, consult more widely, and take informed

advice as to how a combined amphitheatre excavation and new museum complex could

be made a reality.

Otherwise, hang your heads in collective shame and remember that the shrine

in the amphitheatre which you have dishonoured belongs to the goddess Nemesis.