The

Black

&

White

Picture

Place

Photographs of Liverpool: The Sailors' Home 7: A Short History

by Stephen P. McKay (with additions by Steve Howe)

My interest in the Liverpool Sailors’ Home started because of my love of classic British Television. The enjoyment of one series in particular, Patrick McGoohan’s enigmatic 1967 The Prisoner, took me to Portmeirion in North Wales where the series was filmed. While relaxing in one of the Village’s cottage apartments I happened to see an old recording of a BBC Wales documentary called “A Love Affair With Life”, made in 1969. In this the visionary architect Sir Clough Williams-Ellis, the creator of Portmeirion, says that he was offered the mermaid panels from the old Liverpool Sailors' Home by the University because it was being destroyed. My interest in the Liverpool Sailors’ Home started because of my love of classic British Television. The enjoyment of one series in particular, Patrick McGoohan’s enigmatic 1967 The Prisoner, took me to Portmeirion in North Wales where the series was filmed. While relaxing in one of the Village’s cottage apartments I happened to see an old recording of a BBC Wales documentary called “A Love Affair With Life”, made in 1969. In this the visionary architect Sir Clough Williams-Ellis, the creator of Portmeirion, says that he was offered the mermaid panels from the old Liverpool Sailors' Home by the University because it was being destroyed.I knew the panels well as their distinctive design of mermaids and dolphins are used in railings and as decorative grills on a number of the buildings in the Village and appear in many scenes in The Prisoner. Those who have stopped to wonder where these strange nautical images may have come from might have thought that they were made for Sir Clough Williams-Ellis to compliment his adopted logo of a mermaid or sea god. But, like the logo itself, Sir Clough had in fact adopted them because they were unwanted and would fit perfectly into the setting of Portmeirion. At the time I had recently moved to Liverpool and was contributing to a ‘Fanzine’ published by the Liverpool Prisoner Appreciation Society. I started off intending to write a short article about the architectural links between Liverpool and Portmeirion but I was inspired to find out more about a building that had been in many ways forgotten. My research into the history of the Sailors’ Home has been a fascinating and rewarding experience, the building had a dramatic and long life and its demolition in 1974 was a great loss to the city. My hope is that the following pages will enable the reader to understand a little more about Liverpool’s maritime history through the story of one magnificent building and its occupants. A Sailor Town

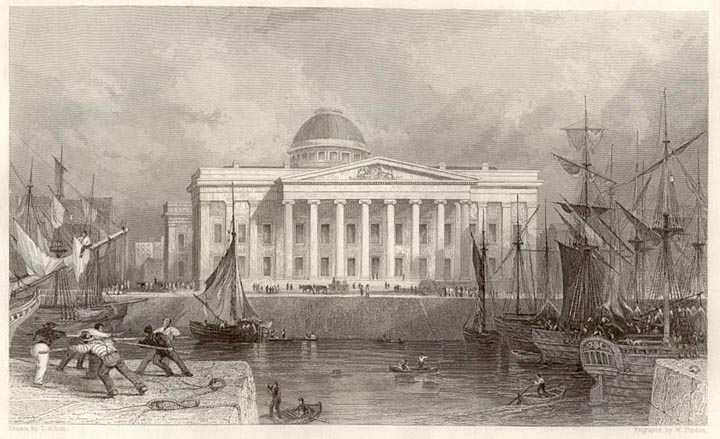

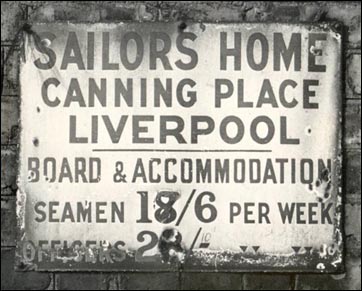

"Of all sea-ports in the world, Liverpool, perhaps, most abounds in all the variety of land-sharks, land-rats, and boarding-house loungers, the land-sharks devour him, limb by limb; while the land-rats and mice constantly nibble at his purse. Other perils he runs, also, far worse; from the denizens of the notorious Corinthian haunts in the vicinity of the docks, which in depravity are not to be matched by any thing this side of the pit that is bottomless. Yet the sailors love Liverpool". A Safe Haven "BOROUGH OF LIVERPOOL Records show that the resulting meeting was lengthy but almost all the speakers were in favour of providing safe lodgings for seafarers in the city and it was resolved to establish a Sailors' Home immediately: . "The immediate objects of this admirable institution are to provide for seamen frequenting the port of Liverpool, board, lodging and medical attendance, at a moderate charge; to protect them from imposition and extortion, and to encourage them to husband their hard-earned wages; to promote their moral, intellectual, and professional improvement; and to afford them the opportunity of receiving religious instruction. A reading-room, library, and savings bank will be attached to the institution; and with a view to securing to the able and well-conducted seamen a rate of wages proportionate to his merits, a registry of character will be kept. Among the ulterior objects in contemplation are schools for sea-apprentices, and the sons of seamen, with special regard to the care of children who have lost one or both their parents." Subscriptions were promptly collected by the committee, who also approached Queen Victoria to be patron of the institution. John Cunningham (of whom more below) was appointed architect. The Corporation offered 900 odd yards of land at the north end of the Prince's Dock for the site of the intended Home but, following planning problems, an alternative site in Canning Place was finally agreed in July 1845. Within a short period after the meeting, the sum of £13,660 was collected and in February 1845 The Sailors' Home Committee got down to the business of formalising the relationship of seamen and their employers. In temporary offices in Bath Street they carried on the duties of shipping masters, charging each seaman shipped, as the Local Marine Board did later, 1 s.6d for engaging him. The Committee undertook this work to protect seamen from the "crimping" system. The loss of this income, when the Government established their own shipping office in 1850, meant that the Home always required private donations and other sources of income to cover the cost of the loss-making boarding and lodging of seamen.

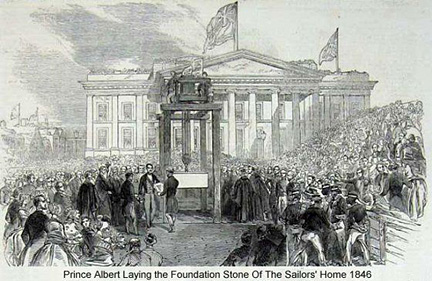

The following day, a procession formed to accompany His Royal Highness from the Judge's House to Canning Place to lay the foundation stone of The Sailors' Home. The procession being formed of: 25 Fire Policemen, a band, 250 Blue Coat Boys, a band, 600 Recabites, a band, 1000 Druids, a band, 1000 Odd-Fellows, a band, 750 Coopers and Blockmakers, a band, 500 Boiler Makers, a band, 1500 Carpenters, a band, 300 Sailors, The Sailors' Home Committee, a Commemorative Trowel, Free Masons, The Corporation, Regalia, The Mayor, The Prince and more Fire Police. The persons forming the procession gathered outside barriers around the sight of the Sailors' Home, overlooked by others perched atop John Foster's Customs House. The sailors, naval officers, the committee of the Sailors' Home and the gentlemen accompanying them, the Freemasons, members of the council, and magistrates of the borough, gathered in the area of the site. H.R.H. was conducted to his place by the Mayor. After the preliminary proceedings by the officers of the Freemasons, the commemorative trowel was presented to the Prince by the chairman of the Sailors' Home Committee who then laid the first stone of The Sailors' Home. It was intended to place copies of all Liverpool newspapers in a glass vase, to be deposited under the stone. Over this was to be placed a steel plate, engraved by Messrs. Vates and Hess, of Lord Street, containing the names of the Committee: Chairman James Akin. Vice-Chairman Charles Cotesworth. Treasurer James Tyrer. Honorary Secretary William John Tomlinson. Chaplain The Rev. William Mayland M.A. Architect John Cunningham. A prayer was offered by the Rev.J.Brooks, AM., senior rector of Liverpool. After the ceremony, His Royal Highness returned to the Judge's house and then caught a train back to London. Queen Victoria noted the events in her Journal after the Prince's return that evening: "The procession, in the morning, composed of 8,000 persons, with 20 Bands, & 5 miles in length, had lasted 4 hours. It went to the place where Albert laid the foundation Stone. He himself drove there, but all the others walked." Unfortunately, the visit of His Royal Highness did not produce all the benefits in respect of increasing the funds of the institution, which was hoped for by The Sailors' Home Committee. Despite this set-back, the construction continued, if at a slow pace and the new building gradually rose in Canning Place. . The Sailor's Home Committee In December the Sailors' Home Opened: "THE SAILORS' HOME (From The Liverpool Courier December 25th 1850).

Over the following two years the Home took on its various functions. In 1851, Schools for Nautical Instruction opened and in May, a bazaar held for the benefit of the building fund, at which curiosities gathered from around the globe by sailors were sold, produced the sum of five thousand pounds. Finally, on Monday December 6th 1852, the Home was opened to receive boarders. The total cost of construction, excluding land, was £30,000. The charge for boarders was 14 shillings per week for men, 10 shillings per week for apprentices. The largest sum received by the Savings Bank Department in any one year at the Bath Street Rooms was £3,302. But the amount at the end of the first year in the new offices was £ 13,000. The other services offered by the Home increased its popularity with seamen. The register of the character of seamen grew, which gave benefits including the ability to cash advance notes at the Savings Bank before sailing. A Dr. Mitchell was appointed as surgeon to attend the Home and in 1857 a School for Sea Apprentices for instruction in reading, writing and arithmetic was commenced, but soon closed, “not being used to the extent expected”. John Cunningham, Architect Born in 1799, John Cunningham was the son of a builder at Leitholm in Berwickshire in the Scottish Borders. At an early age he was noticed by Sir William Purves Hume Campbell, the Sixth Baronet and Third Earl of Marchmont, who helped him with his career. Cunningham’s first known design is a lodge on the Marchmont estate the drawings for which he prepared at the young age of seventeen. He was apprenticed in 1819 to Thomas Brown who was Superintendent of Works in Edinburgh. Back in Berwickshire he was commissioned to design the County Hall and Courts in Greenlaw by the Earl at whose expense the building was erected. The building is designed in the Greek Revival style with Ionic columns in the porch and temple-like wings. The Earl died in 1833 and Cunningham, with his new wife Agnes Usher, emigrated to New York. He may have felt that without the support of his patron he needed to look for work further afield. However the climate did not suit them and Cunningham and his wife returned to Edinburgh in 1834. About this time he was commissioned to design the Castle Inn Hotel opposite the County Hall in Greenlaw. Cunningham was then invited by the successful builder and local politician Samuel Holme to go to Liverpool, where he formed a partnership with Holme’s brother and built up an extensive practice as architect and waterworks engineers, Arthur Hill Holme. Samuel Holme, who was very interested of the Greek Revival style, may have known the County Hall in Greenlaw. The building showed that Cunningham was a very able designer. It is no surprise that one of their joint designs was for Crown Street Station in Liverpool as Samuel Holme was contractor for a number of large railway projects in the Liverpool area and the commission no doubt went their way because of this. Cunningham was a man of wide interests. He was well known for his interest in geology and fossils and was elected Fellow of the Geological Society. He conducted tours to inspect prehistoric footprints left in sandstone in the quarry at Storeton near Liverpool and wrote articles in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. Cunningham remained in Liverpool until 1872. He returned to Scotland and settled in Trinity, Edinburgh. He submitted designs for St Andrews Public Halls (later to become the Mitchell Library and Theatre) in association with the Glasgow-based practice Campbell Douglas & Sellars. Cunningham was seventy-three at this time and he needed help from younger associates. From the beginning it was to be a joint project but Cunningham did not see it through to completion as he died in October 2nd the following year. Perhaps he had regretted that he had not had an opportunity to build a major public hall in his homeland and this project gave him a last chance. A number of his buildings in Liverpool have sadly been destroyed but his Scottish buildings are proof of his quality as a designer. The Building Above the Hanover Street front were five projections, the tops of which were ornamented with shields bearing the "Liver Bird", the "Rampant Lion of Scotland", "St. George and the Dragon", the "Harp of Ireland", and "Anchor and Trident". Unfortunately, this detailed work was carved from the soft, local red sandstone which quickly deteriorated and, being found to be in a dangerous state in 1897, was finally removed completely in 1905 together with the upper portion of the gables above the entrance. This necessary work, sadly, diminished the original character of the building. The cabins in these floors were arranged in fours, with passages of four feet in width between, and the galleries were also each four feet wide, and had direct access on each side to cast-iron stairs, which led down to the Central Hall and up to the roof, which had been made into a promenade with unequalled views of the city, docks, River Mersey and the Welsh mountains beyond.

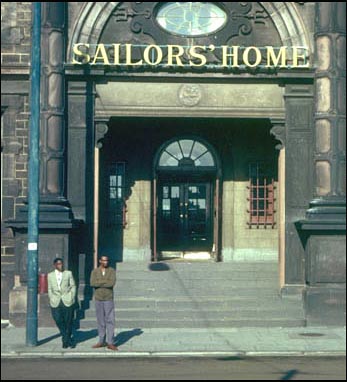

"The "Home" is naturally a centre of attraction for seamen when ashore, whether inmate or not, and crowds of them, of all sorts and nationalities, may daily be met with on the "Mariners' Parade" or in the neighbourhood, offering an excellent opportunity for observation to all who may be interested in the manners and habits of the class." (From a Guide to Liverpool C1870) It is interesting to note that a large number of the Home's residents were coloured. Originally foreign and 'African' seamen were grouped together in the poorest cabins, but by the early 1960s half the occupants of the Home were African and their custom was sorely missed when political problems during the mid 60s kept them away. The Fire From the first day of operations, fire had been identified as a potential threat to the building. Fire plugs with hoses were provided on the two stairways, fed with water from the tanks in the four towers. The Home had only three rules regarding conduct; the third being, "No smoking can be allowed anywhere but in the general hall, nor must Lucifer or other matches be kept in the Home by the boarders." Despite these precautions disaster stuck the Home all too quickly. At about half past twelve on the morning of Sunday, 29th April 1860, the Home's night watchman discovered a fire on the fifth floor which had started in the cabin of a seaman called Charles Jackson. As soon as the fire was discovered, the bedroom stewards roused the inmates. Initially, an attempt was made by Mr Williams, the Superintendent of the Home, to fight the fire using the Home's own equipment but this soon proved futile as the water pressure from the tanks housed in the towers proved insufficient to reach the fifth floor. When the fire spread to the stairways, the remaining occupants on the sixth floor were forced to break through the iron frames of their cabin windows and crawl along a two foot wide ledge which ran along the outside of the building to make their escape down ladders. By one o'clock, the fire police, with 13 or 14 ladders of various lengths and fire engines belonging to the insurance companies, arrived on the scene. The water pressure around Canning Place was unexpectedly low so the water jets could not reach roof height and the iron frames of the windows, with their small panels, also prevented firemen from getting water to the seat of the flames. The fire continued to rage furiously as it consumed the wooden cabins. At about two o'clock, a fireman, Robert Hardaker, fell 40 feet to his death on the stone pavement below when the ladder he was climbing broke. A second man, Joseph Clark, who was neither a boarder nor an employee of the Home but a kind-hearted volunteer, was killed whilst helping to save books and papers from the Savings Bank. He died from terrible injuries sustained when the floor of the dining room fell in and, although many others had a narrow escape, he was caught and crushed between the fallen wreck of the dining room and the floor of the bank. As well as the fire police, many seamen and members of the public distinguished themselves with acts of heroism whilst endeavouring to help residents escape the flames. All the boarders and staff were saved. The number of boarders in the Home at the time was 97, the smallest for some twelve months (the average being about 200). Fortunately, the Spring ships and the easterly winds had almost cleared the port of seamen.

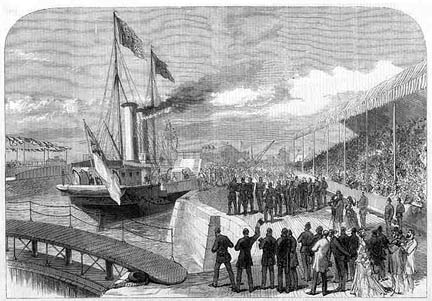

The cause of the fire was thought to be the ash from a lit pipe setting fire to bedclothes. A police officer said that he had seen a box of matches thrown from the building, possibly the third floor, just before the fire burst forth. Charles Jackson vehemently denied that he had been smoking in his room but a member of the staff said he knew him to be careless in such matters because he had seen Jackson, on the morning before the fire, with a lighted pipe burning a hole in his pocket. The insurance, of only £11,000, did not cover the amount of the destruction: "This was thought sufficient. The staircases, the principal rafters, the upright supports etc., being iron, it was imagined that no such destruction could happen as has so unfortunately occurred."- John Hanmer, Secretary, 2nd May 1860. The interior of the Home was restored to its original condition with as little delay as possible, under the direction of the building's designer, John Cunningham, who made some improvements to the original design. The angle of the roof was raised to allow more light and ventilation to the cabins. Iron stoves in the smoking rooms were replaced with open fires to make them more welcoming to the inmates. Wooden joists were replaced with iron. The highly flammable pitch pine of the original cabins was replaced with fire-resistant yellow pine. The hoists, or dumb-waiters, were fitted with iron doors so that they could be used as fire escapes. A fire-proof staircase was also built from the Superintendent's apartments, giving easy access between every floor and the street. The building re-opened on 21st April 1862, the total cost of the renovation being £ 17,000. Raising the difference between this and the £11,000 insurance was put forward to the people of Liverpool as a means of honouring the memory of the late Prince Albert, who had laid the building's foundation stone, and who had sadly died of cholera in the previous year, 1861. The Home was soon welcoming distinguished visitors again. In September 1863, the Channel Fleet, under the command of Admiral Dacers, arrived in the river. The Committee invited one hundred Royal Navy sailors to dine in the Home daily, free of charge, so long as the Fleet remained in port. Decline and Fall During the latter part of the century, the demands on the Home had increased so much that, in 1878, a second "North End Home" was opened, which operated until 1906. The original building was also in need of modernisation. In 1891, an elevator was built in the great hall; this, and its replacement in 1935, badly spoilt the appearance of Cunningham's Central Well. In 1893, re-draining of the building disfigured the exterior with visible iron pipe-work. Between 1903 and 1913, electric lighting was fitted throughout the building, the seamen's cabins being the last part to be connected. During the Great War, 34,553 seamen registered at the Home. 8,080 of these were shipwrecked or distressed mainly as a result of enemy submarine warfare. In 1919, shipping resumed more normal conditions, but the 1920s were yet more years of depression in shipping and consequently seamen found great difficulty in obtaining employment. In 1926, the General Strike caused a prolonged coal stoppage which completely disorganised shipping and increased the demand for accommodation by seamen whose vessels were temporarily placed out of commission. 1930-35 were years of even greater depression during which many vessels were laid up. German bombing of Liverpool failed to cause any serious damage, but its close neighbours were less lucky. In the Liverpool Blitz of 1941, the Customs House was bombed and gutted completely by the resulting fire. Although much of the Classical facade was left intact, it was decided to demolish the shell of the building and after twenty years as an ugly bomb-site car-park, it was replaced by an even uglier glass office block. The Albert Dock was also hit, but was saved by its Victorian fireproof construction; the damage was finally repaired in the 1980's.

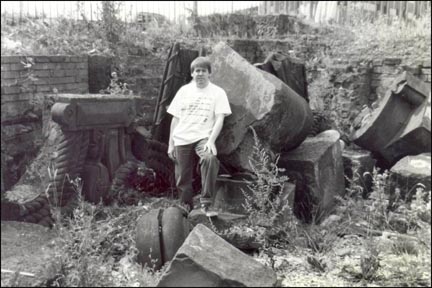

The main entrance of The Home was found to be unsound and the required strengthening necessitated the removal of the magnificent iron gateway. When removed, the Gates were found to be supporting the entrance and a concrete beam carrying the emblem of a sailing ship was used to replace it. This further diminished the beauty of the building. The total capital cost was some £60,000 and it was considered, by the Sailors' Home Committee, "to be a matter of congratulation that the cost had been kept so low in relation to the enormous size of the building and infinitesimally low cost compared with that of a new building capable of accommodating 140 men in the same standard of comfort." On April 23rd 1958, the Lord Mayor of Liverpool visited The Home to inspect all the renovations carried out over the previous few years. A statement handed-out to the Press at the time included the following passage: 'Last year the Shipping Federation Ltd. which had occupied most of the ground floor moved out, and the opportunity was taken of filling the glass ceiling over the premises which was always such an eyesore to the central well of the building. At the same time the central well has been treated to make it more pleasing to the eye and painted in bright colours.' It is during the replacement of the glass ceiling with a new floor that the first-floor balcony railings became redundant. Photographs of the central well after this time show gaps between the supporting columns left when the 65 mermaid railing panels were removed. It is not yet certain how, but approximately half of these panels were acquired by Clough Williams-Ellis who was able to incorporate them into his buildings during the second phase of building at Portmeirion in 1954 following the end of post war restrictions. Despite the sums spent on modernisation, by the early 1960's the home was showing its age and its future became increasingly under question. There were 136,853 bookings representing a daily average of 65 residents for the whole of that period, less than half the Home's total capacity. Cash received from Sailors for Board was £86,892 against ordinary expenditure of £136,625 so that seamen were subsidised to the extent of £49,733 raised by donations, profits on sale of clothing, legacies, canteen and. the interest on investments. By 1969, the Sailors' Home Committee was obviously aware that the old building was uneconomical and in the twilight of its useful life. 13th November 1971: The Committee unanimously agreed to sell the old building and site in Canning Place for the highest bid obtainable as, after a long period of waiting, Liverpool Corporation had given outline planning permission for the development of the site. In 1974, the building was demolished and redeveloped into a hole in the ground leaving the cellar area and foundations, which, apart from some cosmetic stone chippings and the erection of a forest of advertising hoardings, is how the site has been left. It is interesting to note that the hole appears much as it did 150 years earlier in 1845 when Price Albert visited the site to lay the foundation stone. The site was left untouched by developers, probably because of plans set out in the 1960's by Liverpool City Planning Department. These plans resulted in the destruction of many of Liverpool's popular City Centre shopping streets which were replaced by dual-carriageways and marked Canning Place on the intended route for an 'Inner Motorway', not an area suitable for building. It is ironic to note that the Liverpool City Planning Department is currently housed in the office block which was being built on the site of the Customs House just as the Sailors' Home was being evacuated in 1969, as part of its own policy of modernisation, and it is now thought such an eyesore that it may soon be demolished as part of its new plans of re-development for the Canning Place area.

Right: The Sailor's Home in 1970 In the 1840s, few buildings besides railway stations had used cast iron in their construction on a large scale. It was not until the 1880s that similar use was made of iron on a large scale, in American office buildings, such as the Bradbury Building (seen in the film Blade Runner). Like these later constructions, the effect of an upward glance through the balconies was rather vertiginous, yet the sight of all the elaborately articulated iron-work was nevertheless impressive. The iron-work of The Sailors' Home was cast to Cunningham's designs by a local firm, Henry Pooley & Son, who did a lot of ornamental work during the middle of the 19th. century and also supplied the gates of the Liverpool Corn Exchange. Cunningham probably relied on the experience of Henry Pooley Jr. when designing the iron-work of the Sailors' Home. Henry Pooley Senior started his business in Liverpool in about 1800. The Company moved quickly from general casting of iron grates, etc. to the manufacture of heating and ventilation systems. It is as a result of Henry Pooley's designs for these systems that Pooley's became famous for decorative yet functional iron castings. In the 1830s Pooley's also made great innovations in the field of weighing machines, particularly for the weighing of locomotives. Pooley's continued to grow until the business was amalgamated with the Birmingham based scale manufacturer, W.&.T Avery, in 1914. The two foundries "merged" in 1931 and Pooley's Liverpool foundry was probably demolished during the construction of the Mersey Tunnel. Pooley's relationship with the home was not always a smooth one. The heating apparatus was not finished on time and although completed in time for the winter of 1852, failed to 'effect' the purpose for which it was intended'. Another piece of their handiwork had a flaw which resulted in more than inconvenience. 1852 July 14th - "Mr. Cunningham and Mr. Pooley were present in reference to the accident of the falling of the outer gate upon Mrs Price, causing her death. From the explanations given, it seems to have arisen in the neglect of Mr. Pooley's foreman to replace the stop which was carried away when the gate fell before and in the hook attached to the chain having by frequent jerking opened and become detached from the loop upon the gate. Resolved - That Mr.Cunningham & Mr.Pooley arrange an effectual stop for front gate, and that they give a note conjointly, to the effect that the gate shall be made perfectly secure. " The report of the inquest before P.F.Curry on the death Mrs Price failed to mention Pooley's neglect: Mary Ann Price, 52 years of age. John Price, the husband of the deceased, is porter at the Sailors' Home. On the night of Sunday the 12th, between eight and nine O'clock, he was closing the ornamental gate,(which is maSsive iron, and divided into three compartments) which his wife, his daughter, and her child, standing by his side. There was a chain which should have been hooked on to the wall to prevent the gate sliding out of the grooves but this must have been detached by some person unknown to him during the period of divine service. He was shutting the gate in the usual way, when the centre compartment slipped out of the groove and fell upon his wife and daughter, both of whom were taken to the South Hospital where the deceased died next morning from the injuries which she had received. The verdict of the inquest was that Mrs Price had been "Accidentally Killed". 1852 July 21st. "Resolved - That a note be sent to Mr.Pooley to remind him, + to express the extreme disappointment of the Committee that this has been neglected after the late lamented accident. Despite the obvious mechanical problems cause of the fatal accident. The Home's Committee thought that action should be taken against the individual responsible for the gate falling. It was not Mr Pooley or his foreman that were brought to account but the Home's own doorkeeper, Joseph Clark who was suspended and replaced by W m Elliot at 18/- per week.

By 1852 the lower sections of the gates had been installed, decorated with a combination of elements from the interior balconies; four great panels of rope-work with central mermaid and trident figures identical to those inside. The two outer panels were fixed whilst the two centre sections rolled behind them on rails where they were hidden from sight while the Home was open for business. The iron-work of the lower gates being on such a large scale produced a solid, intimidating aspect compared with the much lighter appearance of the balcony railings. The huge mass of iron made an impassable barrier but also a massive weight which so easily crushed the life from its unfortunate victims. The upper part of the gates which reflect the sandstone carvings above the entrance were added later and show a much lighter touch, using the spaces between the iron to great effect. The Minutes of Sailors' Home Management Committee contain the following entry: April 25th. 1852 - "Mr Akin laid upon the Table a note from Mr.Pooley and 2 notes from Mr. Cunningham with a plan for supporting the arch over front gate way. When the superintendent expressed his fears as to the consequences which might result from the proposed spikes upon the top of the gate to drunken belated boarders, and also as to the sufficiency of pillar supports resting upon the top of the gate itself. After some consideration, the matter was referred to Mr. Mann who kindly offered to consult with Mr. Cunningham. " By the following meeting on May 3rd Cunningham had confirmed that he would alter the plan for supporting the front arch to meet Captn. Ainley's suggestion, and on May 24th he was given permission to proceed with the alterations to the front gate way and that Mr.Pooley would have the contract. This might have been all that could be written about the entrance gates until their removal after World War 2, but lightning does strike twice.... November - Police Officer Locke killed through front gate falling upon him. The Tragic Death of Constable Locke Early on the morning of Sunday the 24th of November, nearly an hour after midnight, Police constable number 324A, Brownlow Locke, of the Liverpool City Constabulary, met his death in a very strange and unexpected manner. Constable Locke had gone on duty at 5.45pm. on Saturday evening. A heavy downfall of hail occurred at the time when the porter of the Sailors' Home came out to close the outer gate, which was a solid and heavy iron structure, opened and shut by being wheeled across the opening. The constable, it appears, had left his waterproof cape at another part of his beat, and had stood inside the entrance of the Sailors' Home to shelter from the storm. Seeing the porter unable to pull the mid section of the gate into place, the officer went to his assistance but had evidently given so strong a pull that the gate had run sharply and snapped the hold back chains, one of which was tied with rope. The gate overshot the guide and toppled outwards from the top. The porter during the operation was inside and the policeman outside the gate. Seeing it begin to fall over, the porter made a grab at it, but was overpowered by the heavy mass, and sustained some injury in being carried with it, while the officer, being beneath, sustained the whole impetus of the downfall. Being a mass of metal weighing about half a tonne, the gate crushed the officer so severely that he was at once rendered unconscious. When removed on the ambulance to the Royal Southern Hospital it was found that the injuries, consisting of a fracture of the 'scull' and internal injuries, so serious as to preclude the hope of recovery. About 1.30 on Sunday morning Thomas Locke, who was also a constable in the City Force, was informed that his brother had been injured and taken to Hospital. He immediately proceeded to the institution. His brother, who was unconscious, expired a few minutes after he arrived. Locke, who originally came from Widnes, was described as a very promising officer of twenty six years of age, who had four years service. He left a widow and one child. The victim of the calamity was the fourth member of his family in police service, two brothers serving in the Liverpool Constabulary and one in Sf. Helens. The heavy mass of iron which caused the officer's death lay prone alongside of the front of the building for some time and was an object of curious investigation by morbid passers-by who knew of the sad affair.

At the inquest on the constable’s death, Mr. A. E. Frankland representing the Home, stated that 'he wished to take the opportunity on behalf of the management of the Sailors' Home of expressing their great regret at the accident and also their deep sympathy with the deceased's relatives'. Despite fierce public declarations, on December 5th the Committee met to consider the suggestion of Mr Duder's (the prosecuting solicitor) that the Home should make an offer to the Policeman's widow. After discussing the matter and consulting with Mr. Pedder who advised there was no legal liability in the matter, it was decided that he should see Mr Duder and repudiate liability but ascertain whether the widow would be prepared to accept an ex gratia payment as a mark of the Committee's sympathy - any such payment to be without prejudice in every way to the legal position of the Committee of the Home. The secretary was instructed to get gate inspected by Killick and Cochran and estimate from them for making it secure against such an accident in future". At the next meeting of the Committee on December 23rd - "The Chairman reported that in regard to the Policeman's widow, the matter was still in process of settlement. The Chairman presented Messrs. Killick and Cochran's suggestion an estimate for placing a new wrought iron top guide rail for gates, the Secretary was instructed to request them to proceed with the work at once and to ascertain if they consider the ground runners in good order and also if the new chains supplied by them had been tested and to what extent. A certificate was obtained from the Mersey Chain Testing Works, dated January 21/08 giving the test applied to the chains of the front gate as proof strain applied 6 Cwt, Safe load 3 Cwt the secretary reported that Messrs. Killick & Cochran had told him the chains were amply strong for the purpose. At the same time the Chairman presented the report and balance sheet for 1907, which was passed subject to £ 100 being carried to a suspense to cover a grant for Policeman Locke's widow and costs. Other authorities also made provision for the Constable's widow, but they were not overgenerous. The Merseyside Police Pensions Index for January 20th 1908, show record a gratuity of £25 4 shillings paid to Ellen Locke widow of Constable Locke aged 25. (Thanks to Tony Mossman of the Liverpool Police). Visitors to Anfield Cemetery will look in vain for any monument to Constable Locke, whose grave is unmarked despite the unusual nature of his passing and the pomp and ceremony of his burial. Disturbed by the death of Constable Locke the Chairman approached the Homes' solicitors Messrs. Weightman, Pedder & Co. to determine their liability with regards to third parties having accidents whilst in the Home. The news was not good for the individual Committee members. They were personally liable for the consequences of the negligent action of their servants and liable for injuries happening in consequence of the defective condition of the premises. Fearing the financial penalties in the event of other accidents the Committee quickly resolved that a policy be taken out for £1000 for anyone accident and a maximum of £2000 in one year. Records do not show if a claim was ever made against this policy.

On June11th 1951 it was reported that the gates were 'quite improperly' holding up the archway above them, and considerable work would be necessary before they dare be removed by the Sailors' Home Contractors. Despite this report the gate had been in place for nearly one hundred years and had supported the entrance arch, just as John Cunning ham and Henry Pooley Jnr. had intended when they set down their plans in April 1853. On December 1st. 1951 the gates were finally loaded on to a lorry for transport to the Avery Historical Museum in Soho Birmingham. These magnificent gates now stand rather forlornly at the edge of Avery's car park inside the factory grounds. They have been altered to swing open like conventional doors rather than slide apart as originally intended; the chains which would have prevented them sliding too far are however still present. The gates are now no longer used and appear to have been permanently sealed closed. The mermaids on the four iron panels have suffered fin loss and other signs of damage which photographs show occurred before the 1930's. This may be malicious damage caused by seamen angry at being locked out of the Home after curfew, or during the three occasions, two of them deadly, when the chains failed to stop the massive doors coming off the rails. Sir Clough's Acquisition Another panel was sold through the shop to Cecily Isabel Fairfield, better known as Dame Rebecca West, author of The Balkan Trilogy. List of Sailors' Home railings used by Sir Clough Williams-Ellis: Back of Bridge House (1958-9): one centre section TOTAL: 37 When it was known that despite its status as an Ancient Monument, the future of the Liverpool Sailors' Home was in doubt, efforts were made to create a lasting record, even the building itself could not be saved. In 1962 an architectural and photographic survey was made by members of the Liverpool University school of architecture. A second photographic survey of the then vacated home was made in 1969 for the National Monuments Record and a final series of photos taken by The National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside just before the buildings' destruction in 1974. Salvage Most of the salvaged mermaid railings ended up In the Museum's Stores together with three original curved windows from the officers' bedrooms. Amazingly two complete cabins were also dismantled. Fritz retained the rope-work sections and a number of the mermaid panels which, matching the architectural details, he intended to use some of these as decorative railings on his own house. Unfortunately they were stolen from outside Fritz's home despite being securely chained whilst awaiting planning permission. Although the number of a vehicle was taken when two suspicious people were seen taking an unusual interest in the iron-work and flakes of the original paint were found inside the vehicle when it was stopped by police some time after the theft; the police took the matter no further. Frltz looked In vain for the railings In the yards of Liverpool's many scrap metal dealers. The two mermaid sections he now possesses and others he has given to friends, including one in the south of England to decorate a house called Mermaid Cottage, have been given to him by Liverpool Museums in thanks for his assistance with their rescue. It is possible that the lost railings, like those from the first floor level not collected by Sir Clough, may have been re-used and just wait to be rediscovered, but it is much more likely that despite their beauty and antiquity, they were melted down for scrap. In the spirit of Sir Clough, Fritz tried to preserve some of Liverpool's architectural heritage by constructing follies from salvaged fragments in his large garden in Princes Park. He has built a summer house incorporating, as windows the curved mermaid and rope-work sections of balcony from the Sailors' Home; the roof is supported by circular pillars taken from houses on Upper Parliament Street, the door frames are half square columns from a Doctor's house in Everton and the two front windows are decorated with replica figures copied from ones at the Bluecoat Chambers. Although Fritz's summer house was built without plans and is given a slightly squashed appearance by the shallow pitch of the roof, it was built with love and would not look out of place in the woods of Portmeirion. The Museum Stores also contain the Following panels: Central Piece with two columns of dolphins

Following an open letter to the readers of the Liverpool Echo requesting more information on the Sailors' Home, I was contacted by local photographer Stan Roberts, who not only had photographs he had taken prior to the Homes' demolition but knew of some sections of the Sailors' Home railings that support the counter of the Audlem Mill Canal Shop on the Shropshire Union Canal. In Audlem can be found a unique collection of curved corner sections used with imagination by the proprietor, John Stothert to support the shop's counter. The seven sections were acquired by his brother Tom in 1976 from his old comrade from the Liverpool Philharmonic, Fritz Spiegl. A variety of panels had been created to navigate the four uneven corners of the inner court- at Audlem five can be seen; a mermaid supported by two columns of dolphins which has one straight side and one curved, mermaids with only one dolphin, mermaids but no dolphins, two columns of dolphins without a mermaid, and three columns of dolphins. John says that when he received the railings their pink paintwork was embellished with such features as red lips and purple hair, "They had so many layers of paint on them that you couldn't see the scales on the fishes or the nipples on the women". Layers of pink, red and green paint had to be removed before the panels could be repainted in white. A number of former apprentices from the training ship Conway, which was moored in the Mersey, have visited the shop over the years and recall being sent to paint the mermaids when other duties aboard ship were scarce. Tom Stothert also recalls sections of the railings going under the hammer at Sotheby’s for a surprisingly high amount sometime in the early 1980s. |

Liverpool Gallery | Gallery Introduction | Old Pictures of Chester and Liverpool | B&W

Picture Place

General Index | Site Front

Door | Contact us | Liverpool Airport

Liverpool Gallery | Gallery Introduction | Old Pictures of Chester and Liverpool | B&W

Picture Place

General Index | Site Front

Door | Contact us | Liverpool Airport

In the 1840s Liverpool was described as a 'city of palaces', after the luxurious homes built for the ship-owners who were making vast fortunes from the Slave Trade. But for the ordinary merchant seamen, the City appeared much less glamorous; in his autobiographical novel

In the 1840s Liverpool was described as a 'city of palaces', after the luxurious homes built for the ship-owners who were making vast fortunes from the Slave Trade. But for the ordinary merchant seamen, the City appeared much less glamorous; in his autobiographical novel  Prince Albert Visits Liverpool

Prince Albert Visits Liverpool Here we see the medal that was struck to commemorate the founding of the Liverpool Sailor's Home. It states at the bottom, "His R H Prince Albert laid the foundation stone July 31st 1846". The rear of the medal bears his portrait.

Here we see the medal that was struck to commemorate the founding of the Liverpool Sailor's Home. It states at the bottom, "His R H Prince Albert laid the foundation stone July 31st 1846". The rear of the medal bears his portrait.  The exterior of the building was of the style attributed to the Elizabethan architect Robert Smythson, and resembles his wonderful

The exterior of the building was of the style attributed to the Elizabethan architect Robert Smythson, and resembles his wonderful  Mass Observation

Mass Observation The fire finally died out towards six o'clock the following morning. The building was almost completely gutted; the shell was left filled with half-burnt rafters, staircases and stairs, window frames, portions of stonework and pieces of flooring. However, since the flames were able to escape up through the well of the central hall, apart from the north-west angle, the outer walls of the Home were relatively undamaged.

The fire finally died out towards six o'clock the following morning. The building was almost completely gutted; the shell was left filled with half-burnt rafters, staircases and stairs, window frames, portions of stonework and pieces of flooring. However, since the flames were able to escape up through the well of the central hall, apart from the north-west angle, the outer walls of the Home were relatively undamaged.  Reconstruction (Enter Sir Clough)

Reconstruction (Enter Sir Clough) Men of Iron

Men of Iron The Pooley Gates

The Pooley Gates Constable Locke was buried three days after the accident at Anfield Cemetery. The coffin was conveyed from his home in Rutland-street on one of the Fire Brigade's hose carriages, which was covered with wreaths. About 200 of the deceased's colleagues in uniform followed the cortege. Large numbers of people assembled all along the route. The neighbourhood of the deceased was crowded by sympathetic friends. The chief mourners were the widow and the mother of the deceased and his three brothers (Police-constables Robert, Alfred, and William Locke). Many police officials also attended included two Chief Superintendents. Among others present was Mr Hanmer, the manager of the Sailors' Home. Wreaths were sent from a liverpool's police divisions and from the Sailors' Home.

Constable Locke was buried three days after the accident at Anfield Cemetery. The coffin was conveyed from his home in Rutland-street on one of the Fire Brigade's hose carriages, which was covered with wreaths. About 200 of the deceased's colleagues in uniform followed the cortege. Large numbers of people assembled all along the route. The neighbourhood of the deceased was crowded by sympathetic friends. The chief mourners were the widow and the mother of the deceased and his three brothers (Police-constables Robert, Alfred, and William Locke). Many police officials also attended included two Chief Superintendents. Among others present was Mr Hanmer, the manager of the Sailors' Home. Wreaths were sent from a liverpool's police divisions and from the Sailors' Home. A Sailor's Farewell

A Sailor's Farewell This accounts for approximately half of the railing panels removed from the Home during the post war improvements.

This accounts for approximately half of the railing panels removed from the Home during the post war improvements. A further panel is also out on loan and on display at the Museum of Iron, part of the

A further panel is also out on loan and on display at the Museum of Iron, part of the