arely, if ever, can an area which measures less than one

square mile have encompassed death in so many of its facets. This dubious distinction must surely be bestowed on the old village of Spital

Boughton, perched precariously on top of steep banks overlooking the River Dee,

just outside Chester. arely, if ever, can an area which measures less than one

square mile have encompassed death in so many of its facets. This dubious distinction must surely be bestowed on the old village of Spital

Boughton, perched precariously on top of steep banks overlooking the River Dee,

just outside Chester.

To

start this morbid story at the beginning, one must return to the early 12th

century when was established, on or near what we still call The Mount, a leper hospital, the Sigillum Infirmorum De Cestrie, and chapel dedicated to St. Giles (the patron saint of cripples and lepers)-

and, for those whose treatment proved less than efficacious,

an adjacent graveyard. Subsequently, they were both used to give succour to,

and then to bury, the victims of the great plagues of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Said to have been founded by Ranulph II, Earl of Chester, the hospital survived for nearly 500 years, caring first for lepers and then for the sick of Chester until it was totally destroyed during the English Civil War. It stood on the southern side of Christleton Road behind West Mount. The site, in a disused graveyard, was marked by an inscription in 1935.

In addition to the benefits provided by the Earl, the hospital came to possess land and rents in and near Chester, some of which came with new inmates. For example land in Eastgate Street was given by the relatives of Yseult, who, "smitten by the scourge of a visitation from on high", had been admitted to the hospital.

When Henry III annexed the earldom of Chester after 1237 he was a generous patron of the hospital. He also allowed the lepers a tithe of the expenses of the royal household at Chester, allegedly in continuation of a grant by the earls of Chester. When Henry III annexed the earldom of Chester after 1237 he was a generous patron of the hospital. He also allowed the lepers a tithe of the expenses of the royal household at Chester, allegedly in continuation of a grant by the earls of Chester.

On his accession, Edward I reduced alms to the hospital to the customary payment of 20 shillings a year.

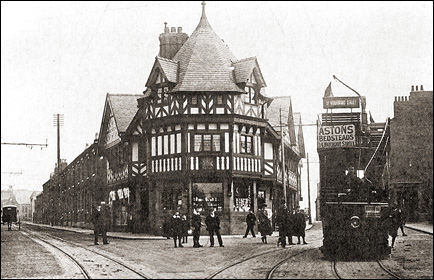

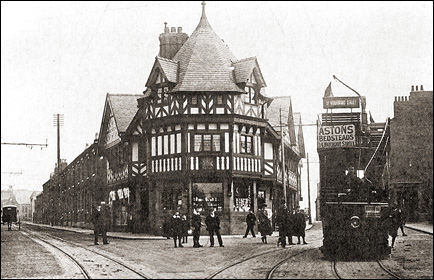

Left: This ornate building of 1900 by the prolific Chester architect John Douglas stands on the site of the ancient Boughton Chapel- demolished during the Civil War- and at the junction of two Roman roads. Among the buildings cleared to make way for it was a pub by the name of The Oddfellow's Arms (see The Vanished Pubs of Boughton).

This photograph dates from around 1910 but, except that the area is now besieged by heavy traffic, the view remains substantially the same today. The handsome building currently houses, of all things, a garage door manufacturer's showroom.

There were few signs of royal favour or interest in the 14th century apart from the regular confirmation of the privileges of the hospital and a grant of £3 6s 8d by the Black Prince in 1353.

The relations of the hospital with the citizens of Chester and the monks of St. Werburgh's Abbey were not always happy. Around 1300 the masters were involved in legal disputes concerning detention of rents, tolls or alms, the Dee fishery, and usury. The tolls claimed by the hospital on all victuals bought for sale in Chester were particularly resented by the tenants of the abbey. The privilege of collecting these tolls was threatened in 1537 when the city authorities pointed out that, whereas it had originally been granted to relieve the sick, the inmates of the hospital were by then "able-bodied"and it was ordered that admissions should be confined to the sick of the city of Chester on penalty of loss of the market tolls.

By the 16th century the inmates evidently lived in individual houses and kept animals on the land around the hospital. In 1537 they were forbidden to wash food or clothes in the newly built conduit at Boughton (which transported water from the Boughton springs to the town and abbey) and were ordered to prevent their animals damaging the conduit and to see that the pipes were properly covered.

The hospital escaped Dissolution under Henry VIII's Act of 1547, probably because of its charitable activities. The hospital escaped Dissolution under Henry VIII's Act of 1547, probably because of its charitable activities.

By the early 17th century the cottages which made up the hospital seem to have become heritable properties. In 1606 the seven inmates, six men and one woman, agreed not to receive vagabonds and beggars into their houses, to ring their swine, and to fence the hospital lands. In 1619 the right of the brothers and sisters of the hospital to be free of the payment of pannage, pontage and murage was confirmed.

Right: many fine houses now line the banks of the River Dee at Boughton

The hospital of St. Giles did not survive the English Civil War. During the seige of Chester the defending Royalist forces implemented a scorched earth policy around the city as Parliamentary troops advanced and the hospital was one of the victims. On to July 1643 the Chester garrison set fire to the hospital barns and pulled down the houses and "the old chapel of Spital Boughton with the stone barn next to it".

The displaced inmates complained to the mayor that while they were helping to defend the besieged city the soldiers destroyed their houses and plundered their possessions.

When

hostile forces reached Spital Boughton in February, 1644 and constructed entrenched

positions, the defending Royalists launched a gallant, but almost suicidal, attack upon

them. About a hundred Royalists perished and were buried in St Giles's Graveyard

as the Roundheads retreated to regroup.

The enemy returned in September to find the Royalists had, understandably but

illogically, spared the high tower of St. John's Church from their policy to deprive their opponents

of commanding positions. Four artillery batteries were mounted, one in the church tower and the others

on similar elevated vantage points on The Mount, and proceeded to rain down

their deadly lead into the walled city of Chester.

In 1657 the master retrieved one of the bells that had been plundered from the hospital chapel from the Pentice (the forefrunner of the Town Hall, situated next to St. Peter's Church) but it was never re-hung in a new hospital and in 1660 the restored Charles II granted to the mayor and citizens of Chester all the lands of "the hospital or late hospital of Boughton, otherwise Spittle Boughton"as a burial ground. Although the graveyard itself lay outside Chester's boundaries, the king presumably granted

it to the city because so many Royalist soldiers were buried there.

The last interrment took place here in 1854.

While on military matters, one must not fail to mention the Chester Shot

Tower, built in 1799, standing only a few hundred yards away across the

Shropshire Union Canal. This was one of only three such towers built to manufacture

musket shot for the Napoleonic Wars and might, therefore, have been instrumental

in the deaths of many French soldiers.

Right next to St Giles's Hospital and cemetery stood the infamous Gallows Hill (now known as 'Barrel Well Hill'). There, countless criminals were executed, their

last view of life being that of the fair River Dee far below and the Meadows beyond. Here we will only concern

ourselves with its five most contentious victims - a disparate combination of

three "witches" and two priests.

On March 31, 1656, the trial of two of the alleged witches was held in the Commonhall

of Pleas, Chester. Ellen Beach was charged with having "consulted and covenanted

with, entertayned, imployed, ffed and rewarded certayn evill and wicked spirits" to cause the death of one Elizabeth Cowper. On March 31, 1656, the trial of two of the alleged witches was held in the Commonhall

of Pleas, Chester. Ellen Beach was charged with having "consulted and covenanted

with, entertayned, imployed, ffed and rewarded certayn evill and wicked spirits" to cause the death of one Elizabeth Cowper.

Anne Osboston faced a similar charge of bringing about the deaths of Barbara

Pott, then her husband John, "a yeoman," and finally Anthony Booth, "a gentleman."

Seen from the Chester Meadows on the far bank of the River Dee,

the lovely 19th century St. Paul's Church, Boughton now dominates old Gallows Hill

At the following October Sessions Anne Thornton was charged with practising "divellish and wicked acts" to bring about the demise of the three-year-old

son of Ralphe Frinchett, of Eccleston. Despite their pleas of innocence all three were found guilty and hanged at Gallows

Hill on October 15th 1656.

Common criminals met their end at Boughton in great numbers over the centuries. From the Chester Chronicle, 7th October 1791: "To-morrow is the appointed day for the execution of Joseph Allen, alias Booth, alias Old Joe; David Aston, alias Davies; and William Knock, alias Big Joe, alias Walton, for burglary. A new temporary gallows is made for the melancholy occasion, which is intended to be placed opposite the old tree in Boughton, near this city."

The following extract, from a letter dated Chester, September 7th 1771, appeared in the Annual Register for that year :—

"The following is an account of John Chapman, who was executed here for robbing Martha Hewitt, of this county. At the hour appointed he was conducted to the place of execution by a greater number of constables than usual, as there was some suspicion of a rescue by the vast concourse of sailors (he being one of that profession) that accompanied him.

On his setting out, a book was put into his hand by the hangman, which he no sooner received than he threw among his brother shipmates, as he termed them; and they immediately tore it to pieces.

A clergyman then got into the cart, and exhorted him to behave with more decency, and to think of his sudden change; but instead of attending to this admonition, he got up in the cart, and (being pinioned) drove his head in the clergyman's belly, and tumbled him out of the cart. After this he flung himself out, and attempted to run into the midst of the sailors, but was prevented by the irons with which he was loaded. He was then seized and tied by ropes in the cart, and in that manner was tied to the fatal tree. At his arrival there he refused either to hear prayers or to pray himself; therefore two men, together with the hangman, attempted to lift him up, to fix the rope about his neck, in doing of which, he by some means got the hangman's thumb in his mouth, which he almost separated from the hand: he was at last tied up, but with great difficulty."

Besides the Gallows, there was a whipping post, of which it is told that one evening in January 1792, "some daring offenders, not having the fear of the magistracy before their eyes, stript the Whipping Post in Boughton of its furniture, and left it as naked as the backs of the culprits are likely to be in case of detection."

This Whipping Post, though, was not always ussd for that purpose, the place of punishment being changeable; for "at the Quarter Sessions for this city in June 1778, Thomas Griffith was found guilty of maliciously breaking and throwing down a rail belonging to the Canal Company, and was ordered to be whipped from the Northgate to Cow-lane Bridge" and on Saturday, April 16th 1791, a man, convicted at the Sessions for milking a cow and stealing the milk, was publicly whipped through the streets of the city. This Whipping Post, though, was not always ussd for that purpose, the place of punishment being changeable; for "at the Quarter Sessions for this city in June 1778, Thomas Griffith was found guilty of maliciously breaking and throwing down a rail belonging to the Canal Company, and was ordered to be whipped from the Northgate to Cow-lane Bridge" and on Saturday, April 16th 1791, a man, convicted at the Sessions for milking a cow and stealing the milk, was publicly whipped through the streets of the city.

At what date the punishment of burning at the stake for murder was abolished by statute I am unable to state with any certainty, but the last instance in Chester occurred when Mary Heald, a Quakeress, suffered that extreme penalty of the law for the murder of her husband. The long-defunct Chester Courant for October, 1762 recorded that "Mary Heald, of Mere, charged upon oath of having poisoned Samuel Heald, her husband, was committed to Chester Castle, by George Heron, Esq on the 23rd of October, 1762."

Right: a view of Chester from Boughton c.1810.

The affair created intense local interest and hundreds of persons, through the winter of 1762, sought and obtained permission to visit the dungeon in our old Castle in which the unhappy woman was confined, the gaolers taking large amounts as largesse for permitting the wretched exhibition. This went on, winked at by the authorities, until the Easter of 1763, when the County Assizes commenced at the Castle. The Courant again:

"

Chester, April 19th 1763. Last week ended the assize here, when Mary Heald, widow of Samuel Heald, late of Mere, near Knutsford, in this county, yeoman (both of the people called Quakers), was convicted of Petit Treason, in killing her said husband, after twenty years cohabitation; by giving him a certain quantity of arsenick, in a mess of fleetings, on the nineteenth day of October last: of which poison he died, in about four days after taking the same. For which crime she was condemned to be burned, on the day after sentence; but upon application to the judges, they were pleased to respite her execution until Saturday, the 23'd of this instant."

Doubtlessly in this interval of four days efforts were made to try and save the life of the convict; but if so, and whatever they were, they failed: for on the Market Day following, the two Sheriffs of Chester City had most uncongenial work upon their hands, as the following paragraph from the Courant gravely assured us:—

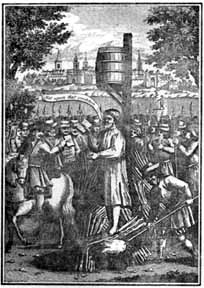

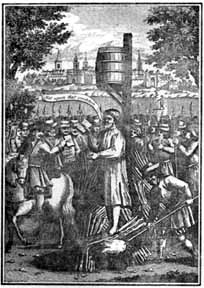

"Chester, April 26th. In our last issue were mention'd the trial and condemnation of Mary Heald; as also, that the judges had been pleased to respite her execution until Saturday, the 23'd inst. Accordingly, soon after ten of the clock in the forenoon of that day, the sheriffs of Chester, with their attendants, came to Gloverstone [neutral ground between City and Castle, just outside the latter's main gate], where the gaoler of the Castle deliver'd to them the said Mary Heald; who, pursuant to sentence, was drawn from thence in a sledge, through the city to Spital Boughton; where after due time having been allowed for her private

devotion, she was affixed to a stake, on the north side of the great road, almost opposite to the gallows: and having been first strangled, faggots, pitch barrels, and other combustibles, were properly placed all around her, and the fire being lighted up, her body was consumed to ashes. This unhappy woman behaved with much decency, and left an authentick written declaration, confessing her crime and expressing much penitence and contrition”.

Now to the luckless, but unrepentant clerics. When the spread of Lutheran protest

was gaining momentum on the continent in the 16th century, and encroaching across

the Channel, George Cotes, only the second Bishop of Chester, became a self-appointed,

vigorous defender of the established faith. It came to his notice, in 1555,

that a clergyman in Lancaster, one George Marsh, was preaching Luther's doctrine. Marsh, a 40-year-old widower with children, was summoned to Chester. There,

in the Lady Chapel of the Cathedral, which was then used as the Consistory Court

of the Diocese, he was charged with having "preached and openly published most

heretically and blasphemously..... directly against Pope's authority and the

Catholic Church of Rome." He was condemned to death and led through the streets

of Chester on his way to Spital Boughton, reading his Bible. There, on Gallows

Hill, he was burned at the stake, his immolation (by all accounts an inefficient

and drawn-out affair, the fire being "mismanaged") being officially witnessed by the Sheriff of Chester.

He was buried in St Giles' Cemetery or, as the Official History of Chester more

graphically puts it, "in it are deposited such of the ashes of the martyr, George

Marsh, as could be collected".

After the Reformation, of course, the boot was on the other foot. In 1674 the

Government instructed Chester's Justices of the Peace to "encourage and quicken

the convictions of popish recusants in the city." From

what one can gather this was pursued with an only token enthusiasm. That is,

until Titus Oats' 'Popish Plot' burst upon the scene in 1678. Oats was a novice

monk who had been rejected as unsuitable from a Jesuit monastery. In revenge he contacted influential Protestants in London and, with their aid,

spread the rumour that the Jesuits were plotting to assassinate King Charles

II. A nationwide panic ensued, followed by a pogrom against the Catholics. After the Reformation, of course, the boot was on the other foot. In 1674 the

Government instructed Chester's Justices of the Peace to "encourage and quicken

the convictions of popish recusants in the city." From

what one can gather this was pursued with an only token enthusiasm. That is,

until Titus Oats' 'Popish Plot' burst upon the scene in 1678. Oats was a novice

monk who had been rejected as unsuitable from a Jesuit monastery. In revenge he contacted influential Protestants in London and, with their aid,

spread the rumour that the Jesuits were plotting to assassinate King Charles

II. A nationwide panic ensued, followed by a pogrom against the Catholics.

The aftermath in Chester was the arrest of John Plessington,

a practicing Catholic priest. He was tried and found guilty of High Treason,

on account of his priesthood.

Taken to Gallows Hill on July 19th 1679, he was allowed to make a speech. Defiantly

he declared: "But I know it will be said that a priest ordayned by authority

derived from the See of Rome is, by the Law of the Nation, to die as a Traytor,

but if that be so what must become of all the Clergymen of the Church of England,

for the first Protestant Bishops had their Ordination from those of the Church

of Rome, or not at all, as appears by their own writers so that Ordination comes

derivatively from those now living."

To the dispassionate observer this may have seemed to have a certain logic.

But, if so, it was lost on his executioners and the unfortunate cleric was hanged, drawn and quartered.

This most horrible and barbaric of punishments prevailed for hundreds of years in England for the most serious of crimes- most notably High Treason. It involved the unfortunate criminal being dragged around the town, and from there to the place of execution on a wooden sledge or pallet, being there hung for a short period, but cut down while still conscious, then having his private parts cut off and burned before his eyes, followed by his belly being slit open and his bowels similarly burned. Trouble was taken to ensure the victim remained conscious and observant throughout the process, which was witnessed by large crowds. Finally, he was beheaded and his torso roughly chopped into four pieces which, together with his head, would be publicly displayed- after being sprinkled with certain spices to prevent the birds pecking at it- in prominent positions around the town, such as upon the city gates- or even in different cities throughout the country.

There the tale of such copious bloodshed might have finished, had it not been

for a lengthy footnote added by one Nessie Brown, who decided in 1898 to erect

a memorial to George Marsh on Gallows Hill. Once the news had spread a furore ensued. There was a considerable number of

Catholics in the city and they staged a series of vehement protests. To their aid came a Mr J. W. Carter, a member of the City Council, who owned

the (recently-demolished) Royalty Theatre in City Road. In those days pantomimes were not solely for

the innocent entertainment of young children, but were also used as vehicles

for the public airing of local political satire. Thus, in his Xmas pantomime he included the following,

Something happened many years ago,

To harp on which stirs strife and animosity.

The folks liked not this fuss about a martyr

And showed their sense by plumping straight for Carter. |

Despite all the hostile feeling engendered, the erection of the memorial received

the sanction of the City Council, and one of the inscriptions carved on it,

which can still be seen, is the name of the mayor in 1898, Dr Henry Stolforth.

The base of the frontispiece states that George Marsh was buried a martyr, "who

was burned for the truth's sake April 24th 1555." On the memorial itself is engraved, "I saw under the altar the souls of them that were slain for the word of God." Despite all the hostile feeling engendered, the erection of the memorial received

the sanction of the City Council, and one of the inscriptions carved on it,

which can still be seen, is the name of the mayor in 1898, Dr Henry Stolforth.

The base of the frontispiece states that George Marsh was buried a martyr, "who

was burned for the truth's sake April 24th 1555." On the memorial itself is engraved, "I saw under the altar the souls of them that were slain for the word of God."

Right: a tram travels through Boughton on a snowy day in 1904

A more harmonious end to the tale was added as recently as 1980 when the memorial

was temporarily taken down to allow for the adjacent road to be widened. During

this interlude it was taken to stonemasons to be renovated, and the suggestion

was made that Plessington's name should be appended to it, as both had been

martyred on Gallows Hill for their respective faiths.

The City Council gave its consent, as did Stephen Brown, nephew of the donor,

Nessie Brown. Restored to its original site, the plinth now bears the inscription "John Plessington Catholic Priest, martyred here on 19th July 1679. Canonised

Saint 25th October 1970."

At long last the religious acrimony has been buried, along with all those departed

souls, whether stricken, courageous, innocent or guilty, and now largely forgotten.

Requiesent in pace. |

arely, if ever, can an area which measures less than one

square mile have encompassed death in so many of its facets. This dubious distinction must surely be bestowed on the old village of Spital

Boughton, perched precariously on top of steep banks overlooking the River Dee,

just outside Chester.

arely, if ever, can an area which measures less than one

square mile have encompassed death in so many of its facets. This dubious distinction must surely be bestowed on the old village of Spital

Boughton, perched precariously on top of steep banks overlooking the River Dee,

just outside Chester. When Henry III annexed the earldom of Chester after 1237 he was a generous patron of the hospital. He also allowed the lepers a tithe of the expenses of the royal household at Chester, allegedly in continuation of a grant by the earls of Chester.

When Henry III annexed the earldom of Chester after 1237 he was a generous patron of the hospital. He also allowed the lepers a tithe of the expenses of the royal household at Chester, allegedly in continuation of a grant by the earls of Chester.

The hospital escaped Dissolution under Henry VIII's Act of 1547, probably because of its charitable activities.

The hospital escaped Dissolution under Henry VIII's Act of 1547, probably because of its charitable activities.  On March 31, 1656, the trial of two of the alleged witches was held in the Commonhall

of Pleas, Chester. Ellen Beach was charged with having "consulted and covenanted

with, entertayned, imployed, ffed and rewarded certayn evill and wicked spirits" to cause the death of one Elizabeth Cowper.

On March 31, 1656, the trial of two of the alleged witches was held in the Commonhall

of Pleas, Chester. Ellen Beach was charged with having "consulted and covenanted

with, entertayned, imployed, ffed and rewarded certayn evill and wicked spirits" to cause the death of one Elizabeth Cowper. This Whipping Post, though, was not always ussd for that purpose, the place of punishment being changeable; for "at the Quarter Sessions for this city in June 1778, Thomas Griffith was found guilty of maliciously breaking and throwing down a rail belonging to the Canal Company, and was ordered to be whipped from the Northgate to Cow-lane Bridge" and on Saturday, April 16th 1791, a man, convicted at the Sessions for milking a cow and stealing the milk, was publicly whipped through the streets of the city.

This Whipping Post, though, was not always ussd for that purpose, the place of punishment being changeable; for "at the Quarter Sessions for this city in June 1778, Thomas Griffith was found guilty of maliciously breaking and throwing down a rail belonging to the Canal Company, and was ordered to be whipped from the Northgate to Cow-lane Bridge" and on Saturday, April 16th 1791, a man, convicted at the Sessions for milking a cow and stealing the milk, was publicly whipped through the streets of the city.

After the Reformation, of course, the boot was on the other foot. In 1674 the

Government instructed Chester's Justices of the Peace to "encourage and quicken

the convictions of popish recusants in the city." From

what one can gather this was pursued with an only token enthusiasm. That is,

until Titus Oats' 'Popish Plot' burst upon the scene in 1678. Oats was a novice

monk who had been rejected as unsuitable from a Jesuit monastery. In revenge he contacted influential Protestants in London and, with their aid,

spread the rumour that the Jesuits were plotting to assassinate King Charles

II. A nationwide panic ensued, followed by a pogrom against the Catholics.

After the Reformation, of course, the boot was on the other foot. In 1674 the

Government instructed Chester's Justices of the Peace to "encourage and quicken

the convictions of popish recusants in the city." From

what one can gather this was pursued with an only token enthusiasm. That is,

until Titus Oats' 'Popish Plot' burst upon the scene in 1678. Oats was a novice

monk who had been rejected as unsuitable from a Jesuit monastery. In revenge he contacted influential Protestants in London and, with their aid,

spread the rumour that the Jesuits were plotting to assassinate King Charles

II. A nationwide panic ensued, followed by a pogrom against the Catholics. Despite all the hostile feeling engendered, the erection of the memorial received

the sanction of the City Council, and one of the inscriptions carved on it,

which can still be seen, is the name of the mayor in 1898, Dr Henry Stolforth.

The base of the frontispiece states that George Marsh was buried a martyr, "who

was burned for the truth's sake April 24th 1555." On the memorial itself is engraved, "I saw under the altar the souls of them that were slain for the word of God."

Despite all the hostile feeling engendered, the erection of the memorial received

the sanction of the City Council, and one of the inscriptions carved on it,

which can still be seen, is the name of the mayor in 1898, Dr Henry Stolforth.

The base of the frontispiece states that George Marsh was buried a martyr, "who

was burned for the truth's sake April 24th 1555." On the memorial itself is engraved, "I saw under the altar the souls of them that were slain for the word of God."