he

building

of

the

weir contributed

greatly

to

the

gradual

silting

of

the

river

Dee-

from

early

times,

Chester

was

the

major

seaport

of

northwest

England,

trading

widely

throughout

Europe

and

supporting

a

thriving

shipbuilding

industry.

he

building

of

the

weir contributed

greatly

to

the

gradual

silting

of

the

river

Dee-

from

early

times,

Chester

was

the

major

seaport

of

northwest

England,

trading

widely

throughout

Europe

and

supporting

a

thriving

shipbuilding

industry.

By

the

reign

of

Henry

VII,

however,

it

was

impossible

for

large

ships

to

reach

Chester

and,

during

the

next

few

hundred

years,

other

harbours

further

along

the

Wirral

coast had

to

be

utilised, or new ones specially built,

as

the

waters

receded,

the

goods

being

unloaded

and

brought

to

the

city

by

flat-bottomed

boats

or

packhorses.

These

harbours, which were collectively known to mariners as the Chester Water, included

Blacon

Point, Burton, Shotwick, Neston, Parkgate, Dawpool, Hoylake and Meols.

Such

have

been

the

changes

that

no commercial ports now exist along the Dee coast of the Wirral Peninsula; the

first

three

of

these

are

now

inland while

the

site

of

the

port

of

Meols,

at

the

tip

of

the

peninsula,

is

now

lost

under

the

waters

of

the

Irish

Sea.

Rich

archaeological

finds

in

this

area

indicate

that

Meols

had

a

long

history

as

a

port,

predating

even

the

Roman

occupation

of

the

region.

Parkgate was,

for

a

period

in

the

18th

century,

the

North

West's

premier

port

for

trade

with

Ireland, Jonathan Swift, Handel and John

Wesley being

but

some

of

the

travellers

who

passed

through

here. It took ships up to 400 tons, some in the Atlantic trade, and it was from here that the troops of Oliver Cromwell embarked to create carnage in Ireland.

Today,

Parkgate

retains

much

of

the

atmosphere

of

an

old

port,

and

its

many

visitors

are

often

surprised

to

see

the

old

harbour

wall

and

period

buildings

surviving

almost

completely

intact-

but

with

hardly

a

sign

of

the

river

that

brought

about

their

establishment. This remarkable 360 degree panorama dramatically illustrates the situation. See also our photograph of the place below...

Today,

Parkgate

retains

much

of

the

atmosphere

of

an

old

port,

and

its

many

visitors

are

often

surprised

to

see

the

old

harbour

wall

and

period

buildings

surviving

almost

completely

intact-

but

with

hardly

a

sign

of

the

river

that

brought

about

their

establishment. This remarkable 360 degree panorama dramatically illustrates the situation. See also our photograph of the place below...

One Emma Lyon, later Lady Hamilton (26th April 1765 –15th January 1815), best remembered as the mistress of Lord Nelson and as the muse of the portrait painter George Romney often visited

Parkgate

for

the

sea

bathing.. She was born Amy Lyon at nearby Ness near Neston, the daughter of a blacksmith, Henry Lyon, who died when she was two months old. She was brought up by her mother at Hawarden in North Wales.

Around

1730,

one Nathaniel

Kindersley, "supported

by

a

number

of

spirited

gentlemen" made

a

survey

of

the

estuary,

and

offered

to

restore

the

navigation

of

the

river

in

return

for

certain

dues

of

tonnage

and

the

profits

of

the

lands

which

would

be

recovered

from

the

sea.

An

Act

of

Parliament

was

passed

to

sanction

the

venture

in

1732,

the

first

turf

cut

in

April

1733,

and

the

waters

of

the

old

channel

were

turned

into

that

of

the

new

just

three

years

later.

Vessels

of

250

tons

could

come

up

to

the

city

for

a

short

time

after

that

with

no

difficulty,

and

in

1740,

The River

Dee

Company was

formed

to

maintain

the

new

cut.

Unfortunately,

a

clause

in

the

Act

stipulated

that

there

should

be "16

feet

of

water

in

every

part

of

the

river at

a

moderate

spring

tide",

but

opinions

varied

widely

as

to

what

was

meant

by

'moderate'

and,

as

a

result,

the

members

of

the

company

had

to

be

"urged

strenuously

and

often" to

fulfill

their

obligations.

The

new,

artificial

watercourse

was

much

narrower

than

the

old

natural

one

and

it

silted

rapidly

and

the

banks

deteriorated.

Arguments

and

litigation

dragged

on,

amazingly,

for

the

next couple

of

hundred

years,

until

1938.

The anonymous author of A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, published in the first years of the nineteenth century, described the situation so, "The act of parliament passed in 1735 gave a number of adventurers, incorporated as 'The River Dee Company', all the land on the north-east side of the channel; this much to the injury of the trade and port of Chester, induced them to conduct the river in a circuitous course, which nearly choaked the navigation; but, from a circumstance of a clause in the act, enabling trustees to seize possession of the land so taken, in case the channel should not be a certain depth, the citizens of Chester, are much indebted to the present laudable exertions of C. Dundas, Esq. and other patriotic gentlemen in the neighbourhood, who have recently adopted measures (agreeable to the intention of the bill) to clear the channel, which we hope may eventually prove a considerable advantage to the City of Chester; the Port of which will in stormy seasons be a haven, void of the great risk of the dangerous banks of Hoyle, which are in the course to Liverpool".

This was sadly not to be and the

increasingly

uneconomic

and

absurdly

self-destructive

situation

contributed

greatly

to

the

rise

of

the

great

port

of Liverpool,

just

a

few

miles

away

on

the River

Mersey,

where

the

world's

first

enclosed

wet

dock

had

been

opened

as

early

as

1715.

The

building

of

the Manchester

Ship

Canal in

the

19th

century

took

even

more

trade

away

from

the

Port

of

Chester.

This was sadly not to be and the

increasingly

uneconomic

and

absurdly

self-destructive

situation

contributed

greatly

to

the

rise

of

the

great

port

of Liverpool,

just

a

few

miles

away

on

the River

Mersey,

where

the

world's

first

enclosed

wet

dock

had

been

opened

as

early

as

1715.

The

building

of

the Manchester

Ship

Canal in

the

19th

century

took

even

more

trade

away

from

the

Port

of

Chester.

Our

little sketch map

dramatically

illustrates

the

decline

of

the

once-mighty

River

Dee: Green indicates

the

riverbank

in

Roman

times, Brown is

land

reclaimed

from

the

marshes-

the 'Sea Lands'- Yellow shows

the

dangerous

and

constantly-shifting

sandbanks,

the Sands

of

Dee and

the

thin Blue line

indicates

the

modern,

greatly-reduced

course

of

the

river. A

number

of

the

ancient

harbours

are

also

indicated.

'The Bar of Chester'

A bar is a bank of sand, silt, etc., deposited at the mouth of a river and, in an estuary so much encumbered by sandbanks as the River Dee, the term applies, in particular to the West Hoyle Bank. The first reference to the Bar of Chester appears to be the one contained in a description of the district written in the 16th century by John Leland, the King's Antiquary. He states that "The Barre called Chester Barre, that is at (the) very mouth of the sandes spuid out of Dee Ryvor, is an 8 or 10 mile west south west from Hilbyri, that is, near the north coast of Flintshire somewhere between Prestatyn and a point two miles west of it."

Inelegant as is the expression used by Leland in modern ears, it aptly describes the continuous unrest of the shifting sands in the Dee Estuary.

It would appear that the position of the "Bar," as given by Leland, was not of the main sand-bank itself but of that part of it which extended across the channel used by ships and covered by sufficient water to allow them passage at the higher phases of the tides. The main sand-bank extended as far as Hilbre Island, adjoining to which the Horse and Rock Channels permitted an alternative access to the Dee by way of the Hoyle Lake, near the north coast of Wirral. At low states of the tide the sandbanks at the mouth of the Dee were uncovered, and this condition is well illustrated by an account of a disaster which occurred in l806 in which the King George packet with 165 passengers and the whole of the crew, with one exception, were lost. The boat set out from Parkgate for Dublin on the ebb tide in fair weather, but  grounded near Hilbre and was soon high and dry. The only course was to wait for the next tide, and to pass the time, most of the passengers descended from the vessel and spent the day walking and running on the sand-bank. In the night a gale blew up, before the King George was fully afloat, and she was driven higher up the bank, and broke up.

grounded near Hilbre and was soon high and dry. The only course was to wait for the next tide, and to pass the time, most of the passengers descended from the vessel and spent the day walking and running on the sand-bank. In the night a gale blew up, before the King George was fully afloat, and she was driven higher up the bank, and broke up.

Right: Parkgate, the best preserved of the lost ports of the River Dee. The quay wall (your guide is standing on it to take the photograph) and many old buildings survive intact but, as can clearly be seen, the water has long since vanished. Parkgate today is a wonderfully evocative place and a visit there is highly recommended- its ice cream, fish and chips, beer and view of the setting sun are unmatched. Learn more about it here.

In 1808 Hoyle Lake is described, on account of its lights, as a fit place for vessels bound up the River Dee "when towards evening they have not tide sufficient to go over Chester Bar".

The extent of the Bar in the direction of Chester appears to have been of rather elastic application. For instance, the tower and spire of the church of the White Friars in Chester was taken down in 1597 and an old chronicler laments this for a number of reasons, one being that it was "the only seaman's mark for direction over the Barre of Chester."

Although this spire was a particularly lofty one it certainly would not be visible from the neighbourhood of Rhyl, and a vessel would probably have to be a considerable distance up the estuary itself before the spire could be seen, owing to the high ground at Blacon Point intervening.

A lightship was formerly moored off the Point of Air ('Y Parlwr Du'), called the Bar Lightship. Dr. Crick, Bishop of Chester, wrote that, when he was chaplain to the Mersey Mission to Seamen, and in charge of the steam launch "Good Cheer" he paid regular visits to various lightships, and, on one occassion, when visiting the Bar Lightship, his boat ran aground on part of the Hoyle Bank.

The

Bridgegate

Returning our attention to Chester, standing

opposite

the

end

of

the

Old

Dee

Bridge

is

another

of

the

ancient

entrances

through

the City Walls-

this

is

the Bridgegate,

designed

by the architect Joseph

Turner and

erected

in

1782.

On

a

marble

tablet

over

the

western

postern,

is

the

following

inscription:

Returning our attention to Chester, standing

opposite

the

end

of

the

Old

Dee

Bridge

is

another

of

the

ancient

entrances

through

the City Walls-

this

is

the Bridgegate,

designed

by the architect Joseph

Turner and

erected

in

1782.

On

a

marble

tablet

over

the

western

postern,

is

the

following

inscription:

"THIS

GATE

WAS

BEGUN

APRIL

MDCCLXXXII,

PATTISON

ELLAMES,

MAYOR,

AND

FINISHED

DECEMBER

OF

THE

SAME

YEAR,

THOMAS

PATTISON,

MAYOR.

THOMAS

COTGREAVE,

HENRY

HESKETH

ESQ.,

MURENGERS,

JOSEPH

TURNER,

ARCHITECT."

On

another

tablet,

on

the

south

side:

"THIS

GATE,

HAVING

BEEN

LONG

INCONVENIENT,

WAS

TAKEN

DOWN

A.D.

MDCCLXXXII.

JOSEPH

SNOW,

ESQ.

MAYOR.

THOMAS

AMERY,

HENRY

HEGG,

TREASURERS"

At

the

time

of

the

Bridgegate's

completion,

news

came

through

of

the

victory

over

the

French

fleet

in

the

West

Indies,

and

on the

back

of

the

tablet

was

engraved:

At

the

time

of

the

Bridgegate's

completion,

news

came

through

of

the

victory

over

the

French

fleet

in

the

West

Indies,

and

on the

back

of

the

tablet

was

engraved:

"The

great

and

joyful

news

was

announced

this

day

of

the

British

fleet,

under

the

command

of

Admirals

Rodney,

Hood

and

Drake,

having

defeated

the

French

fleet,

in

the

West

Indies,

taking

the

French

Admiral

de

Grasse,

and

five

ships

of

the

line,

and

sunk

one.

The

battle

continued

close

and

bloody

for

eleven

hours".

(Joseph Turner's massive tomb is in the Overleigh Cemetery, Handbridge. Today it is shamefully neglected, virtually invisible among the undergrowth but here is a photograph of it by the author, taken about 20 years ago when it was somewhat more accessible...)

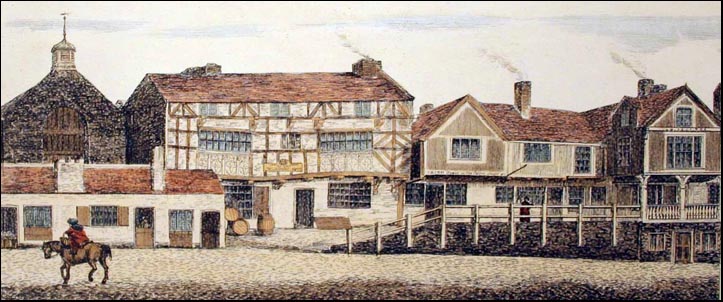

Turner's

arch

replaced

a

strongly-fortified medieval

entrance-

shown

here

in

an

etching

by George

Batenham-

comprising

a

massive

arched

gateway

with

two

strong

towers

on

either

side,

sometimes

known,

because

it

guarded

the

only

direct

approach

to

Chester

from

Wales,

as

The Welshgate.

On

the

gate's

west

side

once stood

a

high,

square-built

water

tower- not the one in our picture-

known

as John

Tyrer's

Tower which

was

constructed

in

1600

to

supply

water

pumped

up

from

the

river

and

distributed

through

lead

pipes

to

wooden

troughs

located

throughout

the

city.

You can see it in the old illustration of the bridge on the previous page.

William

Webb wrote,

about

1615, "This

bridge-gate,

being

a

fair

strong

building

of

itself,

hath

of

late

been

more

beautified

by

a

seemly

water-work

of

stone,

built

steeple-wise

by

the

ingenious

industry

and

charge

of

a

late

worthy

member

of

the

city,

John

Terer,

gent (also

a

lay

clerk

at

the Cathedral) and

hath

served

ever

since,

to

great

use,

for

the

conveying

of

the

river

water

from

the

cistern,

in

the

top

of

that

work

to

the

citzens

houses

in

almost

all

parts

of

the

city,

in

pipes

of

lead

and

wood,

to

their

no

small

contentment

and

commodity".

In

1601,

Gamull

became

a

partner

with

Tyrer

and

agreed

to

supply

water,

in

return

for

which,

it

was

alleged,

Tyrer

agreed

not

to

supply

water

to

those

citzens

who

did

not

deal

with

the

Dee

corn

mills.

The

tower

worked

well

enough

for

half

a

century,

until

being

badly

damaged

during

the

Siege

of

Chester,

and

was

eventually

demolished,

along

with

the

rest

of

the

old

Bridgegate.

(If

you

wish

to

see

for

yourself

how

Chester's

ancient

gates

would

once

have

appeared,

I

recommend

you

pay

a

visit

to beautiful Conwy along

the

North

Wales

coast,

where

the

massive

medieval

defences

remain in

situ,

including

a

complete

circuit

of

walls

and

one

of

the

most

spectacular

of

Britain's

castles).

The octagonal water tower we see in the Batenham picture above was built in 1692 by John Hadley and John Hopkins to replace the one destroyed in the war and this remained until the old gate was demolished in 1782.

The

gates

of

Chester,

with

the

exception

of

the Northgate,

which

was

the

charge

of

the

Mayor

and

citizens,

were

held

in serjeancy,

or

wardenship,

by

noble

families

who

were

responsible

for

maintaining

them

as

defences.

In

turn,

they

were

allowed

the lucrative privilege of

charging

taxes

on

goods

brought

into

the

town

through

their

gate.

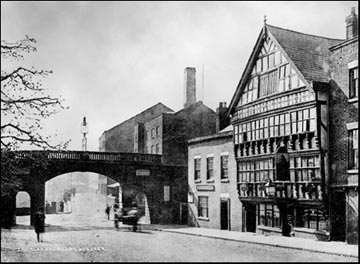

In

the

17th

century,

the

Bridgegate

was

in

the

charge

of

the Talbots,

Earls

of

Shrewsbury,

who,

when

in

Chester,

resided

in

the

splendid

timber

house

you

can

see

on

the

left

inside

the

gate

and

long

known

as

the Bear

and

Billet

Inn,

whose

interior

has been

sympathetically

restored

and

is

well

worth

visiting.

Notice

the

large

doors

at

the

top-

the

opening

to

the

loft

where

goods

were

stored

after

being

hoisted

up

from

the

street.

This

was

common

practice

at

the

time,

the

loft

being

the

part

of

a

house

deemed

most

free

of

damp,

vermin-

and

thieves.

The

windows

on

the

first

and

second

floors

extend

right

across

the

front

of

the

building

and

contain

1,620

quarries,

or

small

leaded

panes

of

glass. It

is

unsure

when

the

building

first

became

an

inn,

though

it

is

said

that

the

Earls

of

Shrewsbury

had

leased

it

to

an

innkeeper,

on

condition

that

a

suite

of

rooms

was

always

kept

available

for

the

Earl

and

his

family.

A

drawing

of

1820

shows

it

as

the Bridgegate

Tavern and

is

believed

to

have

acquired

its

present

name

soon

after.

In

the

17th

century,

the

Bridgegate

was

in

the

charge

of

the Talbots,

Earls

of

Shrewsbury,

who,

when

in

Chester,

resided

in

the

splendid

timber

house

you

can

see

on

the

left

inside

the

gate

and

long

known

as

the Bear

and

Billet

Inn,

whose

interior

has been

sympathetically

restored

and

is

well

worth

visiting.

Notice

the

large

doors

at

the

top-

the

opening

to

the

loft

where

goods

were

stored

after

being

hoisted

up

from

the

street.

This

was

common

practice

at

the

time,

the

loft

being

the

part

of

a

house

deemed

most

free

of

damp,

vermin-

and

thieves.

The

windows

on

the

first

and

second

floors

extend

right

across

the

front

of

the

building

and

contain

1,620

quarries,

or

small

leaded

panes

of

glass. It

is

unsure

when

the

building

first

became

an

inn,

though

it

is

said

that

the

Earls

of

Shrewsbury

had

leased

it

to

an

innkeeper,

on

condition

that

a

suite

of

rooms

was

always

kept

available

for

the

Earl

and

his

family.

A

drawing

of

1820

shows

it

as

the Bridgegate

Tavern and

is

believed

to

have

acquired

its

present

name

soon

after.

'J. H.', a contributor to the Cheshire Sheaf in December 1878 wrote of the old inn, "Not having been touched for many years, the front of the Bear and Billet has assumed a very dilapidated appearance, yet is undoubtedly rich in effect.

The painting of the timber is white, which seems to be unique, and certainly gives a very great contrast, especially in Chester, where we usually look for black timber. I suppose it is a matter o£ taste but I prefer the black, as a more suitable colour both for effect and endurance.

The glazing in the windows of the first floor is also very strange, reminding one of the patchwork counterpanes that are almost peculiar to Cheshire, the quarries are so very much varied.

But I have heard that the front is to be restored and freshened up. I have no doubt that the old building will be tenderly handled under the architect employee to carry out this and the needful alterations to the premises".

But I have heard that the front is to be restored and freshened up. I have no doubt that the old building will be tenderly handled under the architect employee to carry out this and the needful alterations to the premises".

The pub's character changed greatly during modern times- when your guide first visited it in the early 1970s, it was a lively (to say the least) venue popular with the motorcycling fraternity. The passing years found it becoming increasingly neglected and scruffy until, in September 1999, closed

its doors as a public house for the last time (or so we thought) having been taken over by

Benson's Bistro, whose former premises, the historic Gamul House- also in Lower

Bridge Street- was sold to a pizza company. The new owners, in their wisdom- and without planning permission- renamed the

old pub Benson's at the Billet- a decision that found little local

support. But then, in late 2001, it was announced that the ancient name was to be restored and the ground floor once again put back in service as a pub. Some three years later, the pub was indeed once more serving pints but the silly new name unfortunately remained. But, soon after, the long-troubled Billet passed into the care of the Isle of Man based Okell's Brewery and has thankfully once again become an excellent traditional pub offering decent food and a very wide choice of real ales and lagers from around the world.

Collectors of obscure Beatles information will be interested to know that John Lennon's (and his half-sister Julia Baird's) grandmother, Annie Jane Millward, was born in the Bear and

Billet in 1873 and lived there until she was in her 20s. Julia, a longtime former Chester resident, recalled, "Our great-grandfather (John Denbry Millward) and great-grandmother (Mary Elizabeth Millward nee Morris) lived there. Our great-grandfather was the clerk to the Earl of Shrewsbury, because of that he had the freedom to the city of Chester. During childhood, John and I used to spend a lot of time in Chester. We also used to come to Chester on the train from Liverpool as we always knew that Chester was the best place for clothes shopping. We used to go for lunch at Brown's and walk down by the river. Chester has always been in the family. We are the classic family that moved from Wales to Chester to Liverpool. John was very fond of Chester. We always thought Chester was the place to be, not Liverpool."

Annie married George Ernest Stanley, had seven children (the first two died in infancy) - one of whom was John's mother Julia. Annie died in 1941.

The ancient Bear & Billet is thriving but many others have not been so fortunate- go here to

learn

about

the

many Chester

pubs

that

have

ceased to be. A

little

further

on,

on

the

corner

of Shipgate

Street,

and

prominent

in

this

old

engraving,

is

just

such

an

ancient

tavern,

The Old

Edgar,

dating

from

around

1500,

which,

after

years

of

dereliction

was

restored

and

now

serves

as

a

private

residence. A

1905

postcard

advertised

the Edgar

Tavern,

as

it

was

then

called,

as

offering "refreshment

rooms

and accomodation

for cyclists". More pictures of it may be seen in our lost pubs gallery.

The ancient Bear & Billet is thriving but many others have not been so fortunate- go here to

learn

about

the

many Chester

pubs

that

have

ceased to be. A

little

further

on,

on

the

corner

of Shipgate

Street,

and

prominent

in

this

old

engraving,

is

just

such

an

ancient

tavern,

The Old

Edgar,

dating

from

around

1500,

which,

after

years

of

dereliction

was

restored

and

now

serves

as

a

private

residence. A

1905

postcard

advertised

the Edgar

Tavern,

as

it

was

then

called,

as

offering "refreshment

rooms

and accomodation

for cyclists". More pictures of it may be seen in our lost pubs gallery.

Left: a fine Victorian view of the bottom of Lower Bridge Street; the Bear & Billet Inn is on the right, beyond which is the Bridgegate leading to the Old Dee Bridge. With the exception of the looming presence of the Dee Mills beyond the bridge (which burned down in 1914) and, of the course, the absence of traffic, this attractive scene has remained largely unchanged to this day.

Shipgate Street was for centuries a principal entrance to the wharves of Chester's busy seaport and was a place of merchant's houses and sailor's inns until the silting of the River Dee brought about the destuction of the river trade here and its relocating to a new harbour constructed on what was once the bed of the receding river, its site continuing to be be called The Old Port today, even though this, too, has long ceased to be commercially viable. Access to the waterside from Shipgate Street was finally blocked, first by the construction of Harrison's gaol at the end of the eighteenth century and then by County Hall which opened on the same site in 1959. The ancient Shipgate itself was removed and eventually re-erected in Grosvenor Park, where it remains today.

By the 1970s, much of this area had become derelict and a report was drawn up by architect Donald Insall in 1978 which led, in the nick of time, to a programme of radical restoration. Many of the Victorian, Georgian and older houses in the area were restored and some fine new ones constructed and today this part of Lower Bridge Street and Shipgate Street are a delight and well worth visiting when you come to Chester.

There remains one notable exception to this, however, for across the road, on the corner of Duke Street, stands an appalling blot on the face of a beautiful old thoroughfare- an extremely large, ugly and insensitively-situated car showroom / office block. It stands on the site of an ancient group of buildings which went by the name of Old Coach Row which, as may be seen in the detail below from a painting by Louise Raynor (and also in our unmissable gallery of her work here) had steps between the changes in level as it descended steeply southwards towards the Bridgegate and River Dee. The dilapidated condition of the old houses eventually gave rise to the nickname, 'Rotten Row'. Some of the buildings had the characteristics of a true Chester Row, with a covered gallery above cellars entered from the street, whilst others boasted merely an arcade over a raised pavement. Most of the true Rows had gone by 1880 and, by the mid-twentieth century, the frontages had become utilitarian with occasional street-level arcading.

The site immediately to the right of St. Olave's Church was long occupied by a large stone-built structure, resembling a small castle, with a tall tower. This was the home of Richard the Engineer (Richard L'Engenour), the master mason of Chester Castle and, around 1277, the builder of Flint Castle. He was leaseholder of the lucrative Dee Mills just down the road, and was elected Mayor of Chester in 1305. Five years later, the Abbot of St. Werburgh's Abbey (now the Cathedral) commissioned him to build a new Choir.

In 1321, the old building was sold to one Robert Pares (or Praers) and henceforth became known as Pareas Hall- also recorded as Paris's Hall. When this ancient house was demolished is unknown. A building that arose on its site was utilised for some years as a brewery and maltings during the mid and late 19th century. In 1896, for example, the building is recorded as "Chester Northgate Brewery Co, malt kilns". The drawing below, dating from 1880, shows the brewery with St. Olave's on the left (behind a block of long-vanished stables) and Old Coach Row on the right.

In the early 1960s, all of the old buldings between St. Olave's Church and Duke Street were demolished and replaced by a vast and artless concrete showroom- illustrated here- built for the Grosvenor Motor Company and opened in 1962. At the time of writing, December 2010, it has stood empty for several years, boarded up and for sale. Perhaps it's time to knock the awful thing down and replace it with something more in keeping with the area?

Above we see a wonderful image of Lower Bridge Street by the artist Martin Moss, showing the view down towards the Bridgegate as it was in the 19th century compared with today. St. Olave's Church is seen on the immediate left of both pictures but then things rapidly change for the worse as we compare the sadly-vanished Old Coach Row with the ghastly modern building on the same site. You can see a larger version of the older image, plus some other interesting ones, in our Louise Rayner painting gallery...

St. Olave's Church is a charming small sandstone building, standing high above the pavement- a last reminder of that old Row. St. Olave Haraldson was an 11th century king of Norway who helped to establish Christianity in his country. He died in 1030. The church was founded soon afterwards to serve a community of traders from the Norse settlement of Dublin who made this area, situated just outside the line of the Roman wall, their home. The church and its parish were always the smallest and poorest in the city and in 1841 the building was closed and the parish united with that of neighbouring St. Michael's. In 1858-9, Chester architect James Harrison restored the ancient structure to serve as the parochial Sunday school. Since then, it has served in a number of purposes, including aduly education centre, gallery and sale room. A few years ago, however, it was acquired by a Christian group and serves once again, under the name the Chester Revival Centre, in its 1,000-year-old role as a place of worship.

Looking

up Lower

Bridge

Street,

you

can

see

at

the

next

junction St. Michael's

Church which,

standing

as

it

does

close

to

the

site

of

the

vanished

Roman South Gate,

or Porta

Praetoria,

gives

a

clear

indication

of

the

scale

of

the

Saxon

enlargement

of

the

fortress. There has been a church on this spot since the 10th century. Exactly when St Michael's was built is not known, although there are several references to the church towards the end of the 12th century. It was rebuilt in 1582 when thirty-one 'tymber treese' were obtained from Wrexham.

Looking

up Lower

Bridge

Street,

you

can

see

at

the

next

junction St. Michael's

Church which,

standing

as

it

does

close

to

the

site

of

the

vanished

Roman South Gate,

or Porta

Praetoria,

gives

a

clear

indication

of

the

scale

of

the

Saxon

enlargement

of

the

fortress. There has been a church on this spot since the 10th century. Exactly when St Michael's was built is not known, although there are several references to the church towards the end of the 12th century. It was rebuilt in 1582 when thirty-one 'tymber treese' were obtained from Wrexham.

During the Siege of Chester in 1644-6 the church was used as a prison. The Royalist prisoners kept there were "not to have meat, drink, candles, light or tobacco by especial order from the Commissioners, such were their cruelty". Perhaps because of the damage caused during this violent period, the Chancel of the church had become ruined by 1679 and was rebuilt. By 1708, the old wooden steeple and 'clockhouse' was said to be in a poor state and was replaced with a stone tower, surmounted by a cupola.

By the 1840s, the parish had been amalgamated with St Olave's but the interior of St Michael's had become dilapidated and the new tower declared unsafe. The South and East walls were also revealed to be in poor condition, so between 1849 and 1851 virtually the entire church was rebuilt under the supervision of James Harrison (who also, as we read above, was to restore St. Olave's ten years later). Apart from the North Aisle and Chancel roof, which date from the 15th century, most of what can be seen today is Harrison's work.

The church was de-consecrated in 1972 and, after being acquired by Chester City Council, became Britain's first Heritage Centre, opening in 1975. In March 2000, the City Council's archives- all the original documents which were held at the Town Hall- were transferred here and the old building is now the home of Chester History & Heritage, a matchless ambassador for our city and a superb source of information when you want to discover your Chester ancestors or find out about the history of Chester and District.

Just across the road from St. Michael's

long stood

a

church

dedicated

to

the Irish Saint Bridget,

which

was

founded

around

the

year

797

by

King

Offa.

There

is

little

coincidence

in

the

situation;

probably

the

founders

made

use

of

a

ruined

Roman

gatehouse

that

formerly

formed

part

of

the Porta

Praetoria for

their

first

church. The

very

same

situation

seems

to

have

applied

at Holy Trinity

Church (The Guildhall) in

Watergate

Street,

a

Saxon

foundation

sitting

on

top

of

the

site

of

the

vanished

West

Gate

of

the

fortress,

the Via

Principalis

Dextra.

Just across the road from St. Michael's

long stood

a

church

dedicated

to

the Irish Saint Bridget,

which

was

founded

around

the

year

797

by

King

Offa.

There

is

little

coincidence

in

the

situation;

probably

the

founders

made

use

of

a

ruined

Roman

gatehouse

that

formerly

formed

part

of

the Porta

Praetoria for

their

first

church. The

very

same

situation

seems

to

have

applied

at Holy Trinity

Church (The Guildhall) in

Watergate

Street,

a

Saxon

foundation

sitting

on

top

of

the

site

of

the

vanished

West

Gate

of

the

fortress,

the Via

Principalis

Dextra.

St.

Bridget's

was

demolished

in

1825

to

make

way

for

a

road

leading

to

the

newly-constructed Grosvenor

Bridge.

Looking

at

the

site

today,

it

is

difficult

to

believe

that

a

church

stood

for

over

a

thousand

years-

preceded

by

a

great

Roman

gateway-

in

what

is

now

the

middle

of

the

busy

junction

of

Bridge

Street

and

Grosvenor

Street.

A

new

church

of

the

same

dedication,

designed

by the prolific Chester architect Thomas

Harrison (no relation to James),

was

erected

soon

after

close

to

the Castle,

but

this,

too,

was

demolished

during

the

1960s

to

make

way

for

a

traffic

island

as

part

of

the

Inner

Ring

Road.

Chester's

ancient

circuit

of

walls and

gates

are

constantly

monitored

by

its city

council

for

damage

and

movement.

In

the

Spring

of

2000,

it

was

noticed

that

the

parapet

of

the Bridgegate-

a

section

of

which

had

previously

been

pushed

to

the

street

by

vandals-

had

experienced

some

weakening

and

the

spandrel

of

the

arch

had

started

to

move

outwards.

Consequently,

a £40,000

programme

of

repairs

was

undertaken

involving

the

insertion

of

38

stainless

steel

rods

through

the

structure

and

16

horizontal

rods

drilled

through

the

parapet. So carefully was the work done that no trace of the radical repairs are visible to the casual observer.

Sadly, it appears that these remedial works proved inadequate as, not too long afterwards, the entire upper structure was encased in scaffolding and protective plywood. Remarkably, at the time of this latest update in July 2015, it remains that way all these years later!

And now it is time to rejoin the wall and amble on towards Chester Castle...