here

is

much

that

remains

mysterious

about

the

early

history

of

the

site

now occupied

by the beautiful

Chester

Cathedral. here

is

much

that

remains

mysterious

about

the

early

history

of

the

site

now occupied

by the beautiful

Chester

Cathedral.

Certainly,

it

occupies

a

large

central area

within

the

former

Roman

fortress

of Deva and

substantial

traces

of

this

doubtlessly still

lie

beneath the present building,

even

including,

it

is

conjectured,

remains

of

a

Roman

temple

dedicated

to Apollo.

And,

in

the

words

of

the

19th

century

Chester

guide

and

author Thomas

Hughes, "that

this

temple

had

itself

supplanted

a

still

older

fane

of

the

superstitious

Druids".

The

later

continuous

occupation

of

the

site

for

well

over

a

thousand

years

by

a

succession

of

church,

abbey

and

cathedral

buildings

has,

however,

understandably

prevented

attempts to substantiate

these

claims.

According

to Henry

Bradshaw,

a

16th

century

Chester

monk

and

scholar,

Christianity

was

introduced

here

in

about

AD140

by Lucius,

King

of

the

Britons.

This

is

entirely

unproven,

but

King

Lucius

certainly

existed

and

is

mentioned

by Bede and Geoffrey

of

Monmouth.

Contemporary

opinion

places

the

coming

of

Christianity

to

Britain

to

c.

AD175-200

and

it

seems

certain

that

missionaries

would

early

on

have

found

their

way

to

the

fortress

of

Deva, home as it was to a cosmopolitan population of soldiers, sailors, merchants and others hailing from all parts of the vast Roman Empire. Just

when

and

where

they

erected

their

first

church

we

have

no

idea,

indeed,

a

permanent

building

may

not

have

appeared

at all until

after

the

abandonment

of

the

fortress

by

the

Legions

early

in

the

5th

century. Recognising

the

inherent

power

of

ancient

Pagan

sites

and

the

reverence

in

which

they

were

held

by

the

people,

the

early

Christians

commonly

utilised

them

for

their

new

churches,

and

an

abandoned

temple

here

in

the

heart

of

the

old

fortress

would

doubtless

have

qualified

as

such

a

prestigious

location.

We

know

that

other

ancient Chester

ecclesiastical foundations were

founded

upon

the

sites

of less venerated structures

such as abandoned Roman

gatehouses- St. Michael's

in Bridge

Street  stands where Deva's South Gate once was and

Holy

Trinity

in Watergate

Street is on the site of the long-vanished West Gate.

(These once-important entrances fell out of use when the City Walls were extended to their present positions by the Saxon re-occupiers over a thousand years ago). stands where Deva's South Gate once was and

Holy

Trinity

in Watergate

Street is on the site of the long-vanished West Gate.

(These once-important entrances fell out of use when the City Walls were extended to their present positions by the Saxon re-occupiers over a thousand years ago).

The Saxon church appears upon this Chester penny of c. AD 920

Evidence of the practice of reoccupying ancient holy sites can be found in a letter from Pope Gregory to Abbot Mellitius (dated to 601 AD) asking him to help Augustine with the conversion of the Anglo Saxons:

"We wish you to inform him that we have been giving careful thought to affairs of the English, and have come to the conclusion that the temples of the idols among that people should on no account be destroyed. The idols are to be destroyed, but the temples themselves are to be aspersed with holy water, alters set up in them, and relics deposited there. For these temples are well-built, they must be purified from the worship of demons and dedicated to the service of the true God. In this way, we hope that the people, seeing that their temples are not destroyed, may abandon their error and, flocking more readily to their accustomed resorts, may come to know and adore the true God."

Interestingly, in October 2001, while investigating the site of a former telephone exchange half a mile or so from the Cathedral in Boughton, archaeologists unearthed a small slab of slate bearing a fragmentary portion of a Latin inscription, susceptum solvit laetus merito- ("gladly and with joy he fulfilled his undertaking to the god who well deserved it").

It was found on the bed of a Roman water channel, 2 metres wide and lined with wood and stone, which eventually dried up and then used as a rubbish tip. A local expert commented "the obvious inference is that this inscription came from a temple. If this is so, then we have the first written reference to a temple in Chester. Because the piece was essentially found in an ancient rubbish tip, it is hard to pinpoint the exact location of where the temple once stood. Chester was such a prominent place in Roman times, it is unusual that we have never found any record of a Roman temple before but this discovery now sets the record straight". It was found on the bed of a Roman water channel, 2 metres wide and lined with wood and stone, which eventually dried up and then used as a rubbish tip. A local expert commented "the obvious inference is that this inscription came from a temple. If this is so, then we have the first written reference to a temple in Chester. Because the piece was essentially found in an ancient rubbish tip, it is hard to pinpoint the exact location of where the temple once stood. Chester was such a prominent place in Roman times, it is unusual that we have never found any record of a Roman temple before but this discovery now sets the record straight".

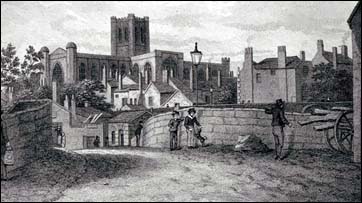

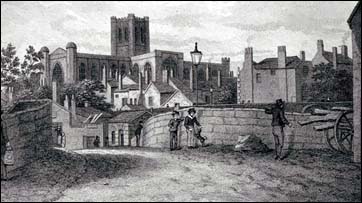

Right: an interesting early 19th century view of the Cathedral as seen from Cow Lane Bridge.

In the winter of 1921-2, during the construction of the War Memorial (illustrated here) between the South Porch and the entrance to the South Transept, the extensive remains of a grand Roman building (the temple?) were unearthed. Lying beneath seven feet of earth and built upon the solid bedrock, were discovered well-built walls four feet in thickness with fine ashlar faces on both sides and built in thin courses of 4-5 inches in depth. Some sections were, curiously, built on top of

flat paving stones, themselves lying on the sandstone bedrock- a rather unnecessary procedure, one would have thought, but one which may point to the fact that this wall was built upon the remains of an even earlier building. Well formed pieces of cornice were also found, each weighing up to

10 cwt.

It

seems

likely

that

Chester's

first

Christians

suffered

along

with

their

fellows

during

the

waves

of

persecution

which

regularly

swept

over

the

Roman

Empire.

During the course of describing the death of the first English martyr, Alban,

at Verulamium (modern St. Albans)

in

AD

301, Bede recorded that, "Diocletian

in

the

East

and

Herculius

in

the

West ordered

all

churches

to

be

destroyed,

and

all

Christians

to

be

hunted

out

and

killed.

This

was

the

tenth

persecution

since

Nero

and

was

more

protracted

and

horrible

than

all

that

had

preceded

it.

It

was

carried

out

without

any

respite

for

ten

years,

with

the

burning

of

churches,

the

outlaw

of

innocent

people

and

the

slaughter

of

martyrs". It

seems

likely

that

Chester's

first

Christians

suffered

along

with

their

fellows

during

the

waves

of

persecution

which

regularly

swept

over

the

Roman

Empire.

During the course of describing the death of the first English martyr, Alban,

at Verulamium (modern St. Albans)

in

AD

301, Bede recorded that, "Diocletian

in

the

East

and

Herculius

in

the

West ordered

all

churches

to

be

destroyed,

and

all

Christians

to

be

hunted

out

and

killed.

This

was

the

tenth

persecution

since

Nero

and

was

more

protracted

and

horrible

than

all

that

had

preceded

it.

It

was

carried

out

without

any

respite

for

ten

years,

with

the

burning

of

churches,

the

outlaw

of

innocent

people

and

the

slaughter

of

martyrs".

Bede,

who

wrote

his

great History

of

the

English

Church

and

People at Jarrow in

remotest

Wearside

in

North

East

England

in

the

first

half

of

the

eighth

century, during the so-called Dark Ages, also

recorded

that, "In

the

same

persecution

suffered

Aaron

and

Julius,

citizens

of

the City

of

the

Legions" ( that being the meaning of Chester's name).

The Cloisters at Chester Cathedral: left, by George Cuitt (1779-1854) and below, by Steve Howe 1992

St. Werburgh

So far, very much is romantic conjecture but what is certain

is

that,

around

the

year

690,

the

Anglo-saxon

princess Werburgh (also here),

daughter

of Wulfhere,

King

of

Mercia,

and

grand-daughter

of

King Penda,

after "a

life

of

pious

works",

died

and

was

buried

at

Hanbury

in

Staffordshire. Not

much

more

is

now

known

about

her,

beyond

her

royal liniage, her reputation

for

sanctity

and

her

powerful

connections,

with

several

sainted

aunts

and

a

revered

grandmother, St. Sexburgh.

The

author

of

the

1792 Chester

Directory wrote

of

her

early

life: "Werburgh...

who,

the

good

wives

of

the

present

day

will

wonder

to

hear,

took

the

veil

after

living

for

three

years

with

her

husband,

Ceolredus,

in

a

state

of

vestal

purity!

Whether

the

chaste

lady's

immaculacy

was

was

more

ascribable

to

a

constitutional

coldness

or

to

a

spiritual

heat,

historians

have

not

been

kind

enough

to

inform

us;

nor

even

have

they

vouchsafed

to say

what

sort

of

a

man

her

husband

was..."

She

first

became

a

nun

at Ely,

lived

most

of

her

life

at Weedon,

Northamptonshire,

died

at Threckingham in

Linclolnshire

and

was

buried

in Hanbury, Stafforshire. An

account

of

her

life,

written

by

the

Flemish

monk Goscelin at

Canterbury

at

the

end

of

the

10th

century,

told

how

she

was

kind

to

every

creature

of

God,

even

the

wild

geese

that

ravaged

her

fields

at

Weedon.

It

is

said

that,

after

shutting

a

large

flock

of

them

indoors

overnight

as

punishment,

she

pardoned

and

released

them.

Upon

discovering

that

one

of

their

number

was

missing,

having

been

stolen

by

a

servant,

the

birds

came

winging

noisily

back

to

her. Werburgh

understood

the

meaning

of

their

cries,

and,

having

secured

the

release

of

their

fellow,

she

rejoiced

with

them,

saying, "Birds

of

the

air,

bless

the

Lord!" The

whole

flock

then

flew

away

and

never

again

interfered

with

the

land

of

the

blessed

Werburgh. She

first

became

a

nun

at Ely,

lived

most

of

her

life

at Weedon,

Northamptonshire,

died

at Threckingham in

Linclolnshire

and

was

buried

in Hanbury, Stafforshire. An

account

of

her

life,

written

by

the

Flemish

monk Goscelin at

Canterbury

at

the

end

of

the

10th

century,

told

how

she

was

kind

to

every

creature

of

God,

even

the

wild

geese

that

ravaged

her

fields

at

Weedon.

It

is

said

that,

after

shutting

a

large

flock

of

them

indoors

overnight

as

punishment,

she

pardoned

and

released

them.

Upon

discovering

that

one

of

their

number

was

missing,

having

been

stolen

by

a

servant,

the

birds

came

winging

noisily

back

to

her. Werburgh

understood

the

meaning

of

their

cries,

and,

having

secured

the

release

of

their

fellow,

she

rejoiced

with

them,

saying, "Birds

of

the

air,

bless

the

Lord!" The

whole

flock

then

flew

away

and

never

again

interfered

with

the

land

of

the

blessed

Werburgh.

A

few

years

after

her

death,

her

body

was

found

to

be "miraculously

uncorrupted" and

her

tomb

became

an

object

of

veneration.

But,

a

century

and

a

half

later,

around

875,

an

invading

Danish

army

advancing

upon

nearby Repton ("The historic capital of Mercia") made

it

necessary

for

the

Saint's

remains

to

be

moved

to

a

place

of

safety.

The

nuns

made

for

the

famous

walled

city

of

Chester

and

re-interred

their

charge

in

a

Saxon

church

dedicated

to

St. Peter

and

St. Paul,

which

had

been

founded

by Werburgh's father Wulfhere around

AD660, possibly incorporating parts of the old Roman temple.

The

church

was

re-dedicated

to

St. Werburgh

and

St. Oswald

in

907- just over 1100 years ago-

by Aethelflaed,

daughter

of Alfred

the

Great,

who

had

recently

reoccupied

and

extended

the

abandoned

Roman

fortress

as part of here campaign against the Norsemen and

who rebuilt

St. Peter's

at

the

Cross-

where

its

successor

still

stands-

and

to

which

the

dedication

was

transferred. The

church

was

re-dedicated

to

St. Werburgh

and

St. Oswald

in

907- just over 1100 years ago-

by Aethelflaed,

daughter

of Alfred

the

Great,

who

had

recently

reoccupied

and

extended

the

abandoned

Roman

fortress

as part of here campaign against the Norsemen and

who rebuilt

St. Peter's

at

the

Cross-

where

its

successor

still

stands-

and

to

which

the

dedication

was

transferred.

Not

a

trace

of

the Saxon

church

where

Werburgh

was

laid

to

rest

remains

visible

above

ground

today,

although

excavations

during

the

recent

replacement

of

the

nave

floor

revealed stonework which

may

have

formed

part

of

it.

Right: This statue of Werburgh graces the front of the Roman Catholic church also dedicated to her in Park Street, which was founded in 1873.

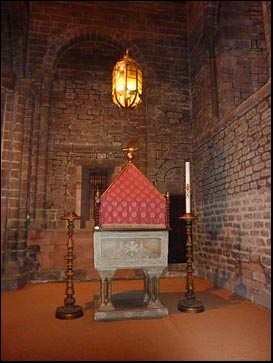

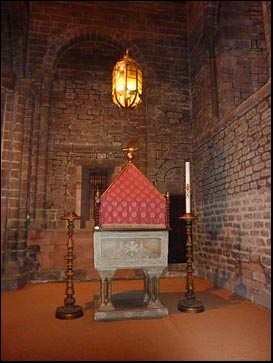

The

Shrine

When

the

mortal

remains

of

Saint

Werburgh

was

brought

to

Chester,

they

were

put

into

a

casket

which

was

eventually,

around

1340,

housed

in

a

beautiful

and

ornate

carved

shrine.

Upon

the

efficacy

of

this

shrine

and

its

relics,

the

church

was

to

gain

a

considerable-

and

exceedingly

lucrative-

reputation

as

a

place

of

pilgrimage.

Henry Bradshaw (died 1513), a monk of the Abbey whom wrote a famous life of the saint,

claimed

that

the

shrine

had

been

responsible

for

miraculous

interventions

that

had

saved

Chester

in

times

of

peril.

For

example,

when

the

Welsh

under

King

Gruffydd

besieged

the

city,

the

shrine

was

lifted

up

onto

the

battlements;

as

soon

as

the

King

looked

upon

it,

he

was

struck

blind

and

the

siege

was

abandoned.

The presence of the saint was given as the reason the Abbey was untouched when much of Chester was destroyed by a succession of disastrous fires.

The

shrine,

once

brightly

painted

and

containing

a

jewel-encrusted

casket

housing

the

relics

of

the

saint,

was

broken

up

on

the

order

of

Henry

VIII

at

the

reformation

when

the

Abbey

itself

was

dissolved,

and

parts

of

it

were actually

incorporated

into

the

fabric

of

a grand throne

contructed soon after for the new Bishop.

In

1876,

its

scattered

portions,

as

many

as

could

be

found,

were

re-assembled

by

one

of

the

cathedral's

restorers, Sir

A. W.

Blomfield,

and

today

the understandably

battered-looking

result

stands

in

the

Lady

Chapel. It no longer houses the bones of Werburgh however, and nobody now knows what became of them.

In

the

time

of King

Aethelstan,

around

AD

975,

a

monastery

was

founded

here and

dedicated

to

St. Werburgh

and

St. Oswald.

In

1057,

Leofric,

Earl

of

Mercia,

largely

rebuilt

the

church

and

gave land for the support of

the

foundation.

After

the

Norman

conquest (Chester was the last city in England to fall, a full three years after the battle of Hastings)

the

Conqueror's nephew and first

Earl, Hugh

D'Avranches, known as Lupus ('the Wolf') and Ermetrude,

his

wife,

transformed

the

building

into

a

grand

Benedictine

monastery,

assisted

by Anselm,

who

later

became

Archbishop

of

Canterbury.

The

first

monks

came

from

the

abbey

of Bec in

Normandy. Work

started

in

1092,

and,

over

the

next

couple

of

centuries,

the

modest

church

was

transformed

into

a

great

monastic

complex,

built

in

the Romanesque style.

Parts

of

this

Norman

building

may

still

be

seen

today,

most

notably

in

the

North

Transept,

where

a

great

arch

and

triforium

survive

unchanged

after

more than

900

years.

The

north-west

corner

of

the

Cathedral

is

the

oldest

part

of

the

nave,

its

original

Norman

end,

with

imposing

rounded

arches

built

around

1140. After

the

Norman

conquest (Chester was the last city in England to fall, a full three years after the battle of Hastings)

the

Conqueror's nephew and first

Earl, Hugh

D'Avranches, known as Lupus ('the Wolf') and Ermetrude,

his

wife,

transformed

the

building

into

a

grand

Benedictine

monastery,

assisted

by Anselm,

who

later

became

Archbishop

of

Canterbury.

The

first

monks

came

from

the

abbey

of Bec in

Normandy. Work

started

in

1092,

and,

over

the

next

couple

of

centuries,

the

modest

church

was

transformed

into

a

great

monastic

complex,

built

in

the Romanesque style.

Parts

of

this

Norman

building

may

still

be

seen

today,

most

notably

in

the

North

Transept,

where

a

great

arch

and

triforium

survive

unchanged

after

more than

900

years.

The

north-west

corner

of

the

Cathedral

is

the

oldest

part

of

the

nave,

its

original

Norman

end,

with

imposing

rounded

arches

built

around

1140.

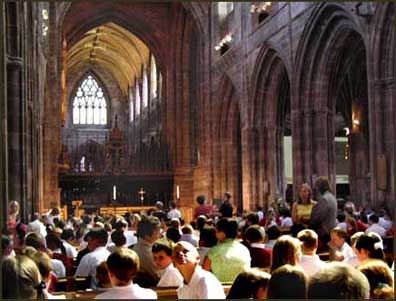

The Cathedral Baptistry set in the Norman North West Tower.

(The

finest

Norman

ecclesiastical

architecture

in

Chester,

however,

is

to

be

seen

in

the

wonderful

building

we

are

to

visit

later

in

our

stroll:

the Church

of

St. John

the

Baptist)

In

1101,

after

a

lifetime

of

excess,

Hugh

the

Wolf, oppressor of the people and father of numerous illegitiate children,

having

over

the

years

become Hugh

the

Fat-

took

Holy

Orders

and

became

a

monk of the Abbey,

doubtlessly

in

a

last-minute

attempt

to

atone

for

his

numerous

sins.

In

the

mid-13th

century,

the

new Gothic style

of

architecture

spread

from

Europe,

first

appearing

at

Chester

in

the

beautiful Lady

Chapel of

c.1260

and

the Chapter

House of

c.1250,

from

where

the

abbey

was

administered

and

the

monks

would

listen

to

a

daily

chapter

from

the

rule

of St.

Benedict.

This

was

also

the

burial

place

of

the

Abbots

and

also

of

most

of

the

Earls

of

Chester.

This

has

one

of

the

finest

vaulted

interiors

of

its

type

anywhere,

a

splendid

example

of

the

first

period

of

native

Gothic

architecture,

the Early

English.

For

the

best

part

of

the

next

three

centuries-

to

the

very

eve

of

the

Abbey's

suppression

in

1538-

work

went

on

continuously

to

produce

the

building

much

as

we

know

it

today. For

the

best

part

of

the

next

three

centuries-

to

the

very

eve

of

the

Abbey's

suppression

in

1538-

work

went

on

continuously

to

produce

the

building

much

as

we

know

it

today.

Set high in the Lady Chapel is this ceiling boss depicting the murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket in 1170. He engaged in conflict with Henry II over the rights and privileges of the Church and was assassinated by knights loyal to the king in Canterbury Cathedral. He was canonized soon after his death. In 1220, Becket's remains were relocated from his first tomb to a grand shrine where it long attracted great numbers of pilgrims. This was destroyed in 1538, during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, on the orders from Henry VIII, who also scattered Becket's bones and ordered that all images of him be obliterated. Even to mention his name was forbidden. Hence Chester Cathedral's relic of Becket is a very great rarity.

The Baptistry (above) is housed in one of the oldest surviving sections of the Cathedral, the Romanesque (Norman) north-west tower, built in the middle of the 12th century. The white marble font was found in a ruined church in Italy and is carved with early Christian symbols such as peacocks (representing the resurrection) and bears the Greek letters alpha and omega. Said to have been made in the sixth or seventh century, its original purpose remains a mystery- perhaps it was the well-head in some long vanished village.

In the Baptistry, also, is to be found a centuries-old board for the ancient game of nine men's morris or merrills scratched into the stone of the plinth of the north east tower- where, perhaps, the monks whiled away some of the little leisure time they enjoyed between services.

The

Chapel

of

St. Nicolas

Like

the

Saxon

minster

before

it,

the

Abbey

served

the

townspeople

as

a

parish

church,

services

being

held

in

the

south

aisle

of

the

nave

at

an

altar

dedicated

to St. Oswald.

With

the

rebuilding

of

the

nave

in

the

14th

century,

they

were

required

by

the

monks

to

move

to

a

former

guild

chapel

dedicated

to St. Nicolas,

which

had

been

built

in

1280,

and

which

is

still

standing

just

across

the

road

from

the

Cathedral

in

what

is

now

St.Werburgh

Street.

Their

new

accomodation

seems

to

have

been

unpopular

with

the

parishioners

as

they

later

returned

to

worship

in

the

exceptionally-large south

transept

of

the

Abbey,

which

was

designated

as

the

Parish

Church

of

St.

Oswald

and

actually walled

off from

the

rest

of

the

building.

This

unusual

situation

continued

until as late as

1872,

when

the

new

Church

of

St. Thomas

of

Canterbury in

Parkgate

Road, one of hundreds of churches designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott-

became

the

church

of

the

Parish

of

St. Oswald.

The

abandoned

chapel

fell

into

disuse

until

the

Abbey

was

dissolved,

when

for

a

time

it

housed

the King's

School before

being

purchased

by

the

town

to

serve

as

a

new

Common

Hall. The

lower

room

was

used

for

the

storage

of

bulk

goods

such

as

cloth,

wool

and

grain "to

be

vended

and

sold

by

Forreiners

and

Strangers,

at

times

allowable

in

the

city"

and

the

upper

room

for "assemblies,

elections

and

courts". The

abandoned

chapel

fell

into

disuse

until

the

Abbey

was

dissolved,

when

for

a

time

it

housed

the King's

School before

being

purchased

by

the

town

to

serve

as

a

new

Common

Hall. The

lower

room

was

used

for

the

storage

of

bulk

goods

such

as

cloth,

wool

and

grain "to

be

vended

and

sold

by

Forreiners

and

Strangers,

at

times

allowable

in

the

city"

and

the

upper

room

for "assemblies,

elections

and

courts".

When

the

new Exchange was

built

in

nearby

Market

Square

in

1695,

the

old

chapel

became

the

Wool

Hall

and

thirty

years

later

was

adapted

for

the

showing

of

plays,

being

greatly

upgraded

in

1773

to

become

the Theatre

Royal,

where

appeared

such

stars

of

their

day

as Sarah

Siddons in

1786

and Edmund

Kean.

Both an Act of Parliament and the personal assent of the Monarch were necessary at this time in order to obtain a licence to open a public theatre and copies of that pertaining to Chester still exist, dating from the early part of the reign of George III, 1761. Audiences didn't sit quietly to enjoy a play as they do today, but would argue and fight among themselves and throw objects and abuse at the performers if their efforts failed to please. Of the Act relating to Chester, it is interesting to note that it was allied to an Act of Queen Anne for "reducing the laws relating to Rogues, Vagabonds, Sturdy Beggars and Vagrants".

The theatre long after remained a source of official suspicion

and plays were required to be licenced by the Lord Chancellor right up to the 1960s.

In

1854

the

building

was

enlarged-

the

new

frontage

being

designed

by James

Harrison-

and

then

became

a

Music

Hall. Charles

Dickens,

who

read

here in 1867,

described

it

thus: "The

hall

is

like

a

Methodist

Chapel

in

low

spirits,

and

with

a

cold

in

its

head".

Dickens seemed to have suffered from the cold excessively in Chester. He wrote that, while staying at the Queen Hotel, "he felt like a piece of meat hanging in a larder". (The Queen, opposite the railway station, remains one of Chester's finest hotels- and is doubtessly rather warmer these days). Dickens seemed to have suffered from the cold excessively in Chester. He wrote that, while staying at the Queen Hotel, "he felt like a piece of meat hanging in a larder". (The Queen, opposite the railway station, remains one of Chester's finest hotels- and is doubtessly rather warmer these days).

The 13th century Chapel of St. Nicolas- much altered and enlarged over the years to accomodate a school, Common Hall, theatre, cinema and a variety of shops- as seen from the roof of Chester Cathedral in 1997. In front of it stands St. Werburgh's Row and in the background the tower of St. Peter's Church at The Cross.. Photograph by the author.

In

1921,

the

Music

Hall

became

the

oldest

building

in

the

world

to

be

used

as

a

cinema

and

showed Al

Jolson's 'talkie' The Singing Fool six

years

later, September 23rd 1929.

(Read about it in our brief history of the cinema in Chester here). It

closed

in

1961

and

became

a

branch

of Lipton's,

the

first

supermarket

within

the

City

Walls.

Since

that

time,

it

has

housed

a

number

of

retail

businesses

and

today

the

venerable

13th

century

Chapel

of

St. Nicolas

plays

host

to

a

branch

of Superdrug.

• It

was

announced

in May

2001 that

Chester's other surviving

old

music

hall

and

theatre,

the Royalty in

City

Road,

was

to

be

demolished, eventually to be replaced by a hotel.

Go here to

see

some

photographs

and learn a little of its fascinating history...

Before

moving

back

into

the

Cathedral,

notice

the

fine

row

of

shops

facing

it

and

adjoining

the

old

chapel: St. Werburgh's

Row,

built

for the Hodkinson Trustees in a sensitive Arts and Crafts style

in 1935. The row was

designed

by Maxwell

Ayrton (1874-1960) who, in partnership with Sir John Simpson,

was

more famously

the

architect

of

the

first Wembley

Stadium,

with

its

world-famous

twin

towers.

Go on to Part II of our exploration of Chester Cathedral...

Curiosities from Chester's

History no. 8 Curiosities from Chester's

History no. 8

- 1354

The

title

'Admiral

of

the

Dee'

first

conferred

upon

the

Mayor

by Edward

the

Black

Prince.

In

the

following

year,

he

granted

the Dee

Mills to

Sir

Howell

Fwyell

for

life,

in

recognition

of

his

bravery

at

the Battle

of

Poitiers.

- 1357

A

fat

ox

sold

for

6s

8d,

a

fat

sheep

for

6d,

a

pig

for

1d.

Labourers

earned

6d

per

day.

- 1362 Piers

Plowman,

poem

in

Middle

English,

ascribed

to

William

Langland

of

Malvern

- 1363

Thomas

de

Newport

becomes

seventeenth

Abbot

of

St.

Werburgh's

(-1386)

- c.1375

The Chester

Mystery

Plays first

performed.

- 1376

Edward

the

Black

Prince

died.

The

following

year,

Edward

III

died

and

his

grandson

Richard,

son

of

the

Black

Prince,

assumed

the

throne

as Richard

II (1367-1400). Robin

Hood first

appears

in

English

popular

literature.

Having

become

an

infamous

refuge

for

vagabonds

and

outlaws,

the Wilderness

of

Wirral,

"was,

on

the

petition

of

the

citizens

of

Chester,

deforested

by

the

order

of

Edward

III:

"His

way

was

wild

and

strange,

by

banks

where

none

had

been...

into

the

wilderness

of

Wirral,

where

few

dwelled

who

granted

any

good

to

God

or

man"

(Sir

Gawain

and

the

Green

Knight)

- 1377

The

Abbot

was

granted

permission

to

crenellate

his

gates

and

boundary

walls

and

the

great

Abbey

Gateway

was

built.

- 1379

A

bushel

of

wheat

sold

for

6d,

a

gallon

of

white

wine

for

6d,

a

gallon

of

claret

for

4d,

a

fat

goose

for

2d

and

a

fat

pig

for

1d.

The Old

Dee

Bridge reconstructed

in

stone,

as

we

know

it

today.

- 1380

The

magnificent

choir

stalls

in

the Cathedral were

installed

this

year.

- 1387-1400

Chaucer: The

Canterbury

Tales. Henry

de

Sutton becomes

eighteenth

Abbot

of

St.

Werburgh's

(-1413)

- 1393

Sir

Baldwyn

Rudistone

and

other

desperados

excite

a

dreadful

riot

in

the

Abbey

Precincts

and

city.

After

killing

one

Sheriff,

taking

the

other

prisoner

and

injuring

the

Mayor,

they

were

finally

expelled

but

returned

a

few

days

after

with

300

men,

and

attempted

to

take

the

place

by

surprise,

but

were

repulsed

and

many

taken

prisoner.

- 1396

Richard

II

marries Isabella

of

France.

The

following

year,

he

visited

Chester

and

was

provided

with

2000

loyal

archers

as

his

bodyguard,

who

wore

his

personal

motif

of

the

White

Hart.

He

was

very

popular

with

the

citizens

and

adopted

the

outlandish

title

of "Prince

of

Chester

for

the

love

he

bare

to

the

Gentlemen

and

Commoners

of

the

Shire

of

Cheshire".

In

September

1397

began

the

Parliament

in

London

for

which

the

King

had

around

him

"a

great

guard

of

Cheshire

men

to

secure

his

person".

|

It was found on the bed of a Roman water channel, 2 metres wide and lined with wood and stone, which eventually dried up and then used as a rubbish tip. A local expert commented "the obvious inference is that this inscription came from a temple. If this is so, then we have the first written reference to a temple in Chester. Because the piece was essentially found in an ancient rubbish tip, it is hard to pinpoint the exact location of where the temple once stood. Chester was such a prominent place in Roman times, it is unusual that we have never found any record of a Roman temple before but this discovery now sets the record straight".

It was found on the bed of a Roman water channel, 2 metres wide and lined with wood and stone, which eventually dried up and then used as a rubbish tip. A local expert commented "the obvious inference is that this inscription came from a temple. If this is so, then we have the first written reference to a temple in Chester. Because the piece was essentially found in an ancient rubbish tip, it is hard to pinpoint the exact location of where the temple once stood. Chester was such a prominent place in Roman times, it is unusual that we have never found any record of a Roman temple before but this discovery now sets the record straight".

She

first

became

a

nun

at

She

first

became

a

nun

at  The

church

was

re-dedicated

to

St. Werburgh

and

St. Oswald

in

907- just over 1100 years ago-

by

The

church

was

re-dedicated

to

St. Werburgh

and

St. Oswald

in

907- just over 1100 years ago-

by  After

the

Norman

conquest (Chester was the last city in England to fall, a full three years after the battle of Hastings)

the

Conqueror's nephew and first

Earl,

After

the

Norman

conquest (Chester was the last city in England to fall, a full three years after the battle of Hastings)

the

Conqueror's nephew and first

Earl,  The

abandoned

chapel

fell

into

disuse

until

the

Abbey

was

dissolved,

when

for

a

time

it

housed

the

The

abandoned

chapel

fell

into

disuse

until

the

Abbey

was

dissolved,

when

for

a

time

it

housed

the  Dickens seemed to have suffered from the cold excessively in Chester. He wrote that, while staying at the

Dickens seemed to have suffered from the cold excessively in Chester. He wrote that, while staying at the