| |

If you walk a short distance past the racecourse and under the arches of the 1840s railway viaduct, you encounter a part of

Chester very different to that of ancient walls, picturesque rows and timbered

houses, known as the Old Port. If you walk a short distance past the racecourse and under the arches of the 1840s railway viaduct, you encounter a part of

Chester very different to that of ancient walls, picturesque rows and timbered

houses, known as the Old Port.

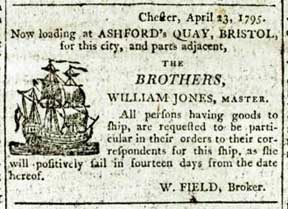

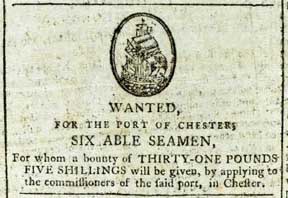

In earlier centuries, the River Dee was a far mightier waterway than it is

today, and large ships could discharge their cargoes at wharves situated immediately

alongside the City Walls.

If you walk down the steps to the racecourse on the Roodee and grub about

behind a lot of brambles, debris and portable buildings, you will be rewarded

with the sight of the massive stones of the Roman

harbour wall, where once war gallies tied up and the trading

ships of the empire discharged their cargoes. Although only a few courses

of these stones now show above ground, they extend for at least another 15

feet underground for much of the length of the wall between here and the Watergate,

with traces of groin walls running off at right angles.

Until the start of the 14th century, the existing structure of the ancient

walls and towers proved adequate to the port's defence, but, as the silting

of the Dee estuary started to badly affect the depth of water available to

shipping, it was deemed necessary to extend the defences further out into

the river, and as a result, in 1322 the Watertower was built.

Try to imagine the scene as early illustrations show it: of armed men looking

down from this spot to where the Watertower stands solidly in the river with

ships moored to its base, the bustle of soldiers, mariners and merchants going

about their business. 16th and 17th century maps of Chester show the River Dee approaching close to the Watergate,

allowing just enough room for a quay for goods to be loaded and unloaded into

waiting vessels or the carts which would be dragged up the steep incline of

Watergate Street to the markets in the city.

Right: Crane Bank in the 1930s Right: Crane Bank in the 1930s

Over succeeding centuries the river silted further, nautical trade seriously

declined and Chester lost its ancient position as the principal seaport of

northern England.

Majestic and gay were the vessels adorning

Thy banks, lovely Dee! as I wandered along;

Where I loved to inhale the pure breath of the morning,

And listen with glee to the mariner's song.

How proudly I gaz'd on thy port that was crowded

With barks that were freighted from India's shore;

Nor thought of the time when thy hopes would be clouded,

And commerce and industry bless thee no more!

But

a

renaissance

came

in

the

1730s

when

the

Dee

was

canalised,

new

quays

and

shipyards

were

established

and New

Crane

Street was

laid

out

to

link

the

new

wharves

to

the

city.

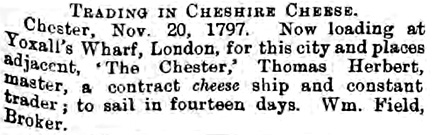

Joseph

Hemingway,

writing

in

1836,

stated

that

the

river

here

"is

navigable

for

ships

of

350

tons

burthen.

From

the

quays

are

exported

some

of

the

richest

cargoes

of

that

excellent

commodity

which

affords

to

the

taste

of

the

Londoners

the

most

grateful

flavour,

and

presents

the

Cockney

with

what

he

calls

"the

fattest

Velsh

rabbits

in

the

Vorld"-

good

old

Cheshire

Cheese".

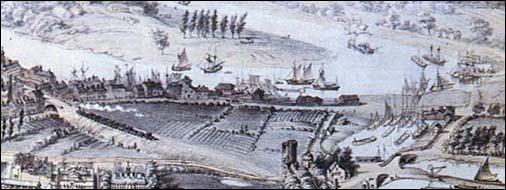

Twenty

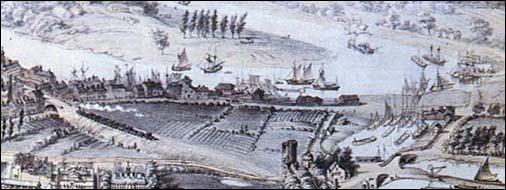

years

later, this remarkable

aerial

view-

a

detail

from

John

McGahey's

famous View

of

Chester

from

a

Balloon- was published,

showing

the

Old

Port

and

its

surroundings

as

they

appeared

around

the

year

1855. A small section of it is illustrated below.

At the end of the nineteenth century, it was proposed that Chester's revolutionary new electricity generating station should be built in the Hop Pole Paddock- better known to us today as The Kaleyards- much to the distress of many, including the Cathedral authorities, who in October 1893 wrote to the council that it "would be a grievous eyesore and a permanent injury to the city itself if that site is so used... Architecturally, the works would seriously effect the Cathedral which is now such an attractive feature of the city... The Chapter have always been desirous of the Hop Pole Paddock being kept as open space for the benefit of the city at large and they are quite willing to approach the Ecclesiastical Commissioners in order to see whether some substantial step can be taken to place the Paddock in trust for the enjoyment of the citizens".

The Mayor assured the Dean and Chapter that their appeal would "receive the careful consideration of the Council" but, by the following January (1894) they had formerly decided that the thing would be built here anyway, despite objections, and also that "having settled on the site, it was not for them to deal with suggestions for keeping open space." (sounds familiar, doesn't it?) The Mayor assured the Dean and Chapter that their appeal would "receive the careful consideration of the Council" but, by the following January (1894) they had formerly decided that the thing would be built here anyway, despite objections, and also that "having settled on the site, it was not for them to deal with suggestions for keeping open space." (sounds familiar, doesn't it?)

In March 1894, the Cathedral authorities offered to pay the sum of £1,000 to purchase the Paddock, but their offer was initially rejected, the committee declaring that this was still the best site for the generating station. A mere month later, however, came an abrupt about-turn when the council decided to accept the Cathedral's £1,000 subject to the following conditions, 1. That it never be built upon and be forever kept open and, 2. That the Chapter relinquish theCorporation a strip of land 12 feet wide at the back of Frodsham Street if and whenever the Corporation require it for widening that street".

The electricity generating station was eventually opened in 1897 here in the Old Port instead, where, after a long resident's battle to fight off a developer's bid to demolish it, it (or at least a token part of it) remains with us today, as we will learn shortly...

With the continuing silting of the Dee and the meteoric rise of the Port of Liverpool,

the shipping faded away (although steam coasters continued to visit Crane

Wharf until the 1930s) and the area continued to decline, to the degree that

if you walk around today, it is difficult to imagine the bustle during the

two hundred years or so of the so-called Old Port's

existence. To the sharp-eyed, however, numerous reminders remain, in the form

of weed-covered harbour walls, the 1730s warehouses (currently serving as

the Sea Cadet's HQ) and quayside buildings such as the Harbourmaster's house

illustrated above. The area nontheless maintained- and continues to maintain-

a thriving residential community and many small businesses: garages, engineers,

hire companies and the like occupy the arches of the railway viaduct. Above

their heads thunder the trains travelling from London to Holyhead and the

boats for Ireland, as they have done for 150 years. With the continuing silting of the Dee and the meteoric rise of the Port of Liverpool,

the shipping faded away (although steam coasters continued to visit Crane

Wharf until the 1930s) and the area continued to decline, to the degree that

if you walk around today, it is difficult to imagine the bustle during the

two hundred years or so of the so-called Old Port's

existence. To the sharp-eyed, however, numerous reminders remain, in the form

of weed-covered harbour walls, the 1730s warehouses (currently serving as

the Sea Cadet's HQ) and quayside buildings such as the Harbourmaster's house

illustrated above. The area nontheless maintained- and continues to maintain-

a thriving residential community and many small businesses: garages, engineers,

hire companies and the like occupy the arches of the railway viaduct. Above

their heads thunder the trains travelling from London to Holyhead and the

boats for Ireland, as they have done for 150 years.

Recently, much new building has occured around the Canal Basin and facing

South View Road- much of which was undertaken by housing associations to provide

new social- and young people's accomodation. This is to be followed by more

new houses on cleared land between Tower Road and South View Road.

So far so good. The area's restoration has been long overdue and the new,

low-rent homes were badly needed. Unfortunately, proposals for the second

phase of the Old Port redevelopment- involving the needless demolition of

the handsome Victorian Electric Lighting Company Building (illustrated right) and its replacement by a series of ugly, overlarge and

inappropriate office blocks- 'artist's impression's' of which may seen below- received, as we shall see,

an extremely hostile reception by the people of Chester.

The Electric Light Building was Chester's first electric

generating station, designed by I. Matthews Jones and built by a forward-looking Corporation in

New Crane Street in 1896, under the auspices of the eminent Professor Kennedy

and overseen by no less than the world famous scientist Lord Kelvin. The men

responsible for the distribution of the electricity were the engineers

F. Thursfield (until 1904) and S. E. Britton (until 1946)- both, sadly, rarely remembered today. The Electric Light Building was Chester's first electric

generating station, designed by I. Matthews Jones and built by a forward-looking Corporation in

New Crane Street in 1896, under the auspices of the eminent Professor Kennedy

and overseen by no less than the world famous scientist Lord Kelvin. The men

responsible for the distribution of the electricity were the engineers

F. Thursfield (until 1904) and S. E. Britton (until 1946)- both, sadly, rarely remembered today.

The three original generators have long disappeared, but in recent years the attractive

office building of the former power station had been occupied by local electricity

provider Manweb. With the ending of their lease, thought had to be

given to the future of the building- considered by many to be an eloquent

symbol of our region's industrial heritage and as such, eminently worthy of

preservation. Architect Francis Graves presented

the case in the Sunday Times for its conversion to a possible exhibition

or 'heritage' centre and restaurant. Not only did Graves recommend retaining

the building for its appearance but noted it as a "central landmark" suitable

for public use, etc. There was, after all, ample space for office development

across the road on the land recently vacated by the gasworks, together with

more houses- which may do something to lift the threat of development in other

parts of the city, such as the much-valued allotments on Cheyney Road and

the Blacon Meadows, to name just two.

Chairman of the Chester Civic Trust, Stephen Langtree, wrote in the Trust's newsletter that "no economically

viable new use could be found for the building" and the council therefore

decided to hold an architectural competition in conjunction with Wilmslow-based

developers F T Patten- with Langtree himself as

one of the judges- to "see whether a scheme might emerge which would enhance

the area and justify the loss of the Victorian building".

These experts plumped

for a design by architects Mills Beaumont Leavey Channon which, believe it or not, "evoked the maritime context through the use of glass cladding, lighting

and external water features." Consequently, we're told, "some of the more

exuberant aspects" of the design were subsequently done away with during the

planning permission process- leaving us with the delightful escapees from

Milton Keynes illustrated here and below... These experts plumped

for a design by architects Mills Beaumont Leavey Channon which, believe it or not, "evoked the maritime context through the use of glass cladding, lighting

and external water features." Consequently, we're told, "some of the more

exuberant aspects" of the design were subsequently done away with during the

planning permission process- leaving us with the delightful escapees from

Milton Keynes illustrated here and below...

Langtree

continued, "I know some of you are deeply unhappy about the loss of the old

Lighting Company Building. It is undoubtedly one of important local interest but is not, we believe, of any great architectural merit. Retaining the facade might have been an option, but part of it straddles a

large old sewer over which no new construction would have been allowed". This

was a crude, easily-exposed untruth, which, as the apparent major reason for

demolition, somehow continued to be repeated- most recently by City Council

Head of Planning Andrew Farrall in the Chester Standard of 6th

August 1998.

Curiously, both Welsh Water and the city council's

own engineers said there was absolutely nothing wrong with the Victorian sewer and no remedial action would be necessary should

the building be retained. Only in the event of its replacement would a three-metre

wide 'exclusion zone' come into operation. And even if there were a problem,

as is pointed out in a letter below, the repair

and replacement of sewers, however large, has been going on for some time

now. The process can be tricky, but is hardly high tech, and certainly does

not require the demolition of existing buildings- otherwise there would be

a lot of gaps in most city centres!

In the words of Councillor Steve Davies (one of the very few elected

representatives to speak up against these absurd proposals)- "I believe the

developers don't want this building, so we are looking at ways to get rid

of it". He felt that the developers- doubtless backed up by elements within

the city council and Civic Trust- did not want to retain the building because

it did not fit in with their bright new 'high tech' image, and would therefore not attract

the 'right sort' of company to occupy it- "This is a historic city, so why

should we welcome developers who want to put up modern offices you could see

in Milton Keynes? The people of Chester placed their trust in us when they

voted for us. Let us not betray that trust or we will earn the same contempt

from future generations that we have for those who pulled down the old Market frontage". In the words of Councillor Steve Davies (one of the very few elected

representatives to speak up against these absurd proposals)- "I believe the

developers don't want this building, so we are looking at ways to get rid

of it". He felt that the developers- doubtless backed up by elements within

the city council and Civic Trust- did not want to retain the building because

it did not fit in with their bright new 'high tech' image, and would therefore not attract

the 'right sort' of company to occupy it- "This is a historic city, so why

should we welcome developers who want to put up modern offices you could see

in Milton Keynes? The people of Chester placed their trust in us when they

voted for us. Let us not betray that trust or we will earn the same contempt

from future generations that we have for those who pulled down the old Market frontage".

In sharp contrast, back to Stephen Langtree: "Retaining a partial facade was,

in the opinion of the Civic Trust Council, a less satisfactory solution than

making way for a new group of three buildings which will untie the space,

providing a 'gateway' to the city and be a commercially stimulating centrepiece

for the revival of the area".

In a similar vein, in the course of reviewing 15 years of conservation

'progress' since European Architectural Heritage Year in 1975, one David

Pearce wrote, "Now the emphasis is on preservation and conservation of

old buildings, and their intelligent adaptation to new uses. And in a bizarre

reversal, old buildings are now too often assumed to have greater intrinsic

merit than any new design". In other words, as this same individual remarked

when adressing Chester Civic Trust in 1989, "We cannot, and must not, try

to keep everything". In a similar vein, in the course of reviewing 15 years of conservation

'progress' since European Architectural Heritage Year in 1975, one David

Pearce wrote, "Now the emphasis is on preservation and conservation of

old buildings, and their intelligent adaptation to new uses. And in a bizarre

reversal, old buildings are now too often assumed to have greater intrinsic

merit than any new design". In other words, as this same individual remarked

when adressing Chester Civic Trust in 1989, "We cannot, and must not, try

to keep everything".

Music, we're sure, to the ears of the planners and developers...

Attempts were made to protect the Electric Light

Building by getting it listed- buildings not needing be particularly ancient

to qualify for this. Harry Weedon's Odeon Cinema of 1936 in Northgate

Street is an example- but 'national experts' declared it to be "only

of local interest" and therefore not worth saving.

Speaking in response to the deeply depressing news that, despite the massive

public outcry against the destruction of the building by people who considered

it a vital part of Chester's industrial history, local campaigner Avril Coady referred to Langtree's weasel words when she said, "We looked to the council

to protect us, but developers have been given the priority yet again. They

took the Civic Trust's comments into consideration when the Civic Trust has no mandate to represent the people of the area. We DO have a mandate.

We've got a 1000-plus signatures from the people who matter- the people who

live in the district".

We heard around this time that the compulsory purchase order on the attractive

Victorian cottages in Kitchen Street, directly opposite the Electric Light

building had been rescinded. Also that the City Council Property Development

Officer responsible for dealing with the Old Port scheme, Craig Booton,

had taken up a job with FT Patten, the developers who wanted to build the

office blocks- presumably taking all his valuable inside knowledge with him.

In

mid-September 1998, Manweb's 50-odd maintainance workers started to "reluctantly"

move from the site where electricity workers have been based for over a century

to their new depot on the Chester West Business Park. The company were unhappy about the move, which was

requested by the city council, but nevertheless said that they left "in order

to assist the council plans for redevelopment in the Old Port area".

Reader Alan Edwards has kindly supplied some of his reminisciences of working for Manweb in the old building:

"I joined Manweb (Merseyside and North Wales Electricity Board) in 1972 as an apprentice telecoms in the Technical Section. I was to be based in Chester at various sites. One of these was Crane Street, the 'New' (of New Crane Street) never seemed to feature in Manweb.

So what was in the Depot? Well, the main job of an Electricity Board was to keep the lights on as it were, aka supply electricity. The main building was a former generating station for Chester and the mountings for the machinery could still be found in the stores area. Various “trades” worked in the depot, electricians who would do repairs and re-wires of properties both industrial and people's homes. Fitters who would maintain and construct substations electrical equipment. Linesmen who maintained and constructed overhead lines. Jointers who worked on underground cables and Engineers who designed the network, looked for faults and switched circuits in and out, these were highly trained people usually with degrees in Electrical Engineering.There was a garage to maintain all the vehicles needed to do these jobs. These were the norm across all of Manweb from Aberystwyth to Southport and over to Oswestry. So what was in the Depot? Well, the main job of an Electricity Board was to keep the lights on as it were, aka supply electricity. The main building was a former generating station for Chester and the mountings for the machinery could still be found in the stores area. Various “trades” worked in the depot, electricians who would do repairs and re-wires of properties both industrial and people's homes. Fitters who would maintain and construct substations electrical equipment. Linesmen who maintained and constructed overhead lines. Jointers who worked on underground cables and Engineers who designed the network, looked for faults and switched circuits in and out, these were highly trained people usually with degrees in Electrical Engineering.There was a garage to maintain all the vehicles needed to do these jobs. These were the norm across all of Manweb from Aberystwyth to Southport and over to Oswestry.

Crane Street, however, had some unique departments. There was the Polyphase Meter Test. This tested and calibrated industrial metering. Ordinary domestic meters were tested in Liverpool. There was protection where the equipment was tested, this stuff was used to “protect” substations and cables and had to be precisely calibrated. In short if someone dug up a cable in the Road or damaged an overhead line the power needed to be disconnected more or less instantly to avoid a fire or even an explosion in the substation. Finally there was the Radio Workshop where I was to spend quite a lot of time though I worked in the other areas too. Manweb had a large radio network right across the company and the equipment to go into the base stations and vehicles was maintained here.

What was it like working there? Pretty good actually, we didn’t take ourselves too seriously and wind ups were very common. Quite a few people worked in the depot obviously, but most people knew each other and would stop for a chat and how's tricks. It was a happy place and people generally looked forward to going to work, I know I did. A colleague once told me that in the 60s when people generally didn’t have cars, everyone would leave the depot en masse and walk into Chester, most would pause in the Watergate Pub for a pint and a natter before heading home.

Privatisation was to end our happy existence and conditions went downhill sadly. Many depots including Crane Street closed and as we know it is now a collection of flats with very little of the original building left. Progress- NOT."

Also in September 1998, and despite the inevitable resident's objections,

the council planning sub-committee unanimously voted for the obliteration

of the last piece of green open space in the vicinity of the Old Port- the

so-called Stone Park (illustrated right in its final days with new

developments rising behind)- by the building of houses and flats. The original

council 'masterplan' for the area showed this proposed development, but also

the closure of Tower Road and the extension of Tower Gardens to reach the

canal bank, thus creating a replacement, easily-accessible park for the benefit

of the community. Also in September 1998, and despite the inevitable resident's objections,

the council planning sub-committee unanimously voted for the obliteration

of the last piece of green open space in the vicinity of the Old Port- the

so-called Stone Park (illustrated right in its final days with new

developments rising behind)- by the building of houses and flats. The original

council 'masterplan' for the area showed this proposed development, but also

the closure of Tower Road and the extension of Tower Gardens to reach the

canal bank, thus creating a replacement, easily-accessible park for the benefit

of the community.

However, once planning permission was obtained, this 'masterplan' was mysteriously

altered, omitting the promised extension to the park. Thus existing- and future-

residents of the area would be deprived of anywhere for their children to

play in safety- the nearby, and very attractive- Tower Gardens contains

a putting course, tennis courts and bowling greens, but nowhere for rollerblades,

bikes and dogs (and in addition is closed all Winter)- and the city as a whole

is to be robbed of yet another badly-needed 'green lung'.

How then, in the face of this ongoing saga of

greed and stupidity, was the citizen to equate the attitudes and actions of

our City Council and their developer friends with the words of Prime Minister

Tony Blair that "Community takes precedence over developers, and people count

for more than buildings"- or of their own, much-vaunted environmental guide, Agenda 21, which declared "The history and heritage of the city and

district are constant reminders of how important the environment is. Agenda

21 will help us to meet the needs of today's society without damaging the

environment, the history and the heritage for future generations".

'Seranus'

Now go on to part two of our brief history of Chester's Old Port...

|

If you walk a short distance past the racecourse and under the arches of the 1840s railway viaduct, you encounter a part of

Chester very different to that of ancient walls, picturesque rows and timbered

houses, known as the Old Port.

If you walk a short distance past the racecourse and under the arches of the 1840s railway viaduct, you encounter a part of

Chester very different to that of ancient walls, picturesque rows and timbered

houses, known as the Old Port. Right: Crane Bank in the 1930s

Right: Crane Bank in the 1930s The Mayor assured the Dean and Chapter that their appeal would "receive the careful consideration of the Council" but, by the following January (1894) they had formerly decided that the thing would be built here anyway, despite objections, and also that "having settled on the site, it was not for them to deal with suggestions for keeping open space." (sounds familiar, doesn't it?)

The Mayor assured the Dean and Chapter that their appeal would "receive the careful consideration of the Council" but, by the following January (1894) they had formerly decided that the thing would be built here anyway, despite objections, and also that "having settled on the site, it was not for them to deal with suggestions for keeping open space." (sounds familiar, doesn't it?)  With the continuing silting of the Dee and the meteoric rise of the Port of

With the continuing silting of the Dee and the meteoric rise of the Port of  The Electric Light Building was Chester's first electric

generating station, designed by I. Matthews Jones and built by a forward-looking Corporation in

New Crane Street in 1896, under the auspices of the eminent Professor Kennedy

and overseen by no less than the world famous scientist Lord Kelvin. The men

responsible for the distribution of the electricity were the engineers

F. Thursfield (until 1904) and S. E. Britton (until 1946)- both, sadly, rarely remembered today.

The Electric Light Building was Chester's first electric

generating station, designed by I. Matthews Jones and built by a forward-looking Corporation in

New Crane Street in 1896, under the auspices of the eminent Professor Kennedy

and overseen by no less than the world famous scientist Lord Kelvin. The men

responsible for the distribution of the electricity were the engineers

F. Thursfield (until 1904) and S. E. Britton (until 1946)- both, sadly, rarely remembered today. These experts plumped

for a design by architects Mills Beaumont Leavey Channon which, believe it or not, "evoked the maritime context through the use of glass cladding, lighting

and external water features." Consequently, we're told, "some of the more

exuberant aspects" of the design were subsequently done away with during the

planning permission process- leaving us with the delightful escapees from

Milton Keynes illustrated here and below...

These experts plumped

for a design by architects Mills Beaumont Leavey Channon which, believe it or not, "evoked the maritime context through the use of glass cladding, lighting

and external water features." Consequently, we're told, "some of the more

exuberant aspects" of the design were subsequently done away with during the

planning permission process- leaving us with the delightful escapees from

Milton Keynes illustrated here and below... In the words of Councillor Steve Davies (one of the very few elected

representatives to speak up against these absurd proposals)- "I believe the

developers don't want this building, so we are looking at ways to get rid

of it". He felt that the developers- doubtless backed up by elements within

the city council and Civic Trust- did not want to retain the building because

it did not fit in with their bright new 'high tech' image, and would therefore not attract

the 'right sort' of company to occupy it- "This is a historic city, so why

should we welcome developers who want to put up modern offices you could see

in Milton Keynes? The people of Chester placed their trust in us when they

voted for us. Let us not betray that trust or we will earn the same contempt

from future generations that we have for those who pulled down the old

In the words of Councillor Steve Davies (one of the very few elected

representatives to speak up against these absurd proposals)- "I believe the

developers don't want this building, so we are looking at ways to get rid

of it". He felt that the developers- doubtless backed up by elements within

the city council and Civic Trust- did not want to retain the building because

it did not fit in with their bright new 'high tech' image, and would therefore not attract

the 'right sort' of company to occupy it- "This is a historic city, so why

should we welcome developers who want to put up modern offices you could see

in Milton Keynes? The people of Chester placed their trust in us when they

voted for us. Let us not betray that trust or we will earn the same contempt

from future generations that we have for those who pulled down the old  In a similar vein, in the course of reviewing 15 years of conservation

'progress' since European Architectural Heritage Year in 1975, one David

Pearce wrote, "Now the emphasis is on preservation and conservation of

old buildings, and their intelligent adaptation to new uses. And in a bizarre

reversal, old buildings are now too often assumed to have greater intrinsic

merit than any new design". In other words, as this same individual remarked

when adressing Chester Civic Trust in 1989, "We cannot, and must not, try

to keep everything".

In a similar vein, in the course of reviewing 15 years of conservation

'progress' since European Architectural Heritage Year in 1975, one David

Pearce wrote, "Now the emphasis is on preservation and conservation of

old buildings, and their intelligent adaptation to new uses. And in a bizarre

reversal, old buildings are now too often assumed to have greater intrinsic

merit than any new design". In other words, as this same individual remarked

when adressing Chester Civic Trust in 1989, "We cannot, and must not, try

to keep everything".  So what was in the Depot? Well, the main job of an Electricity Board was to keep the lights on as it were, aka supply electricity. The main building was a former generating station for Chester and the mountings for the machinery could still be found in the stores area. Various “trades” worked in the depot, electricians who would do repairs and re-wires of properties both industrial and people's homes. Fitters who would maintain and construct substations electrical equipment. Linesmen who maintained and constructed overhead lines. Jointers who worked on underground cables and Engineers who designed the network, looked for faults and switched circuits in and out, these were highly trained people usually with degrees in Electrical Engineering.There was a garage to maintain all the vehicles needed to do these jobs. These were the norm across all of Manweb from Aberystwyth to Southport and over to Oswestry.

So what was in the Depot? Well, the main job of an Electricity Board was to keep the lights on as it were, aka supply electricity. The main building was a former generating station for Chester and the mountings for the machinery could still be found in the stores area. Various “trades” worked in the depot, electricians who would do repairs and re-wires of properties both industrial and people's homes. Fitters who would maintain and construct substations electrical equipment. Linesmen who maintained and constructed overhead lines. Jointers who worked on underground cables and Engineers who designed the network, looked for faults and switched circuits in and out, these were highly trained people usually with degrees in Electrical Engineering.There was a garage to maintain all the vehicles needed to do these jobs. These were the norm across all of Manweb from Aberystwyth to Southport and over to Oswestry.  Also in September 1998, and despite the inevitable resident's objections,

the council planning sub-committee unanimously voted for the obliteration

of the last piece of green open space in the vicinity of the Old Port- the

so-called Stone Park (illustrated right in its final days with new

developments rising behind)- by the building of houses and flats. The original

council 'masterplan' for the area showed this proposed development, but also

the closure of Tower Road and the extension of Tower Gardens to reach the

canal bank, thus creating a replacement, easily-accessible park for the benefit

of the community.

Also in September 1998, and despite the inevitable resident's objections,

the council planning sub-committee unanimously voted for the obliteration

of the last piece of green open space in the vicinity of the Old Port- the

so-called Stone Park (illustrated right in its final days with new

developments rising behind)- by the building of houses and flats. The original

council 'masterplan' for the area showed this proposed development, but also

the closure of Tower Road and the extension of Tower Gardens to reach the

canal bank, thus creating a replacement, easily-accessible park for the benefit

of the community.