aving

safely negotiated busy Grosvenor Road, we, until very recently, would have been immediately struck by the large,

ugly and to my mind, extremely inappropriately-sited building at the junction

with Nicolas Street- the busy Inner Ring Road- on our right. This was the County Police Headquarters, designed by the County architect,

Edgar Taberner and built between 1964 and 1967, at the astonishing cost

for the time of over half a million pounds. aving

safely negotiated busy Grosvenor Road, we, until very recently, would have been immediately struck by the large,

ugly and to my mind, extremely inappropriately-sited building at the junction

with Nicolas Street- the busy Inner Ring Road- on our right. This was the County Police Headquarters, designed by the County architect,

Edgar Taberner and built between 1964 and 1967, at the astonishing cost

for the time of over half a million pounds.

The 'sculpted' ends of this otherwise

drab block were designed by W. G. Mitchell and were made by pouring concrete

onto polystyrene moulds. They actually won a National Civic Trust award in 1969, even though the local branch objected to the building's design. Mind you, three decades later in the pages of 2000 Years of Building, they were praising it again: "It makes an important and positive townscape contribution... a particulary successful link with the castle opposite."

Architectural commentator Nikolaus Pevsner wrote of the building: "Extremely objectionably sited, an eight-storey block immediately

by the propylaea of the castle and turning towards it a windowless wall

with an agressive all-over concrete relief".

The Royal Fine Art Commission criticised the design around the same time. However, Donald Isall, in his influential report of 1968, cited the building as "an example of beneficial change within the city". He found it to be "well related to Grosvenor Street and the Castle."

Incorporated

into

the

lower

parts

of

the

Police HQ

were

sandstone

blocks

from

the

castle-like Militia

Buildings which

formerly

occupied

the

site.

Built

just

after

the

Crimea

War

in

1854-6,

they

were

used

as

married

quarters

for

the

families

of

troops

serving

at

the Castle.

You

can

see

them

in

the

photograph

below,

which

also

shows

Chester's

forgotten

'Beefeaters'-

dressed

similarly

to

their

surviving

brethren

at

the

Tower

of

London-

the Javelin

Men who

once

escorted

the

Judge's

coach

to

the

assizes

at

the

Castle. A fascinating short British Pathé newsreel of them from 1926 may be seen here...

In

February

1998 it

was

reported

that

the

police

intended

to

move

out

of

their "crumbling"

30

year-old

building,

as

it

was

"too

cramped".

The

city

force

had

confirmed

a move

to

the

site

of

the

recently-demolished

Arts

Centre

in

Blacon

and

were

looking

for

a location

for

a city

centre

base

while

their

County

colleagues

wished

to

relocate

elsewhere

in

Cheshire.

The

date

for

this

move

was

said

to

be

sometime

in

2003.

What

then

would

be

the

fate

of

their

present

building

was,

at

the

time,

anybody's

guess-

a

report

that

it

was

to

demolished

to

make

way

for

a hotel

had

been

officially

denied,

which

led most locals to believe that

there was

probably

something

in

it.

Whatever

the

case,

few

would

be

sorry

to

see

it

go-

they

only

hoped

that

the

building

that

eventually

replaced

it

would

be,

for

a change,

something

the

city

could

be

proud

of.

Three years later, in February 2001, the building was formerly put up for

sale and, it was reported, "A number of potential developers, including leading

hotel chains, have made their interest known".

The city council's Design

and Conservation Manager commented that "There are two alternatives, either

keep the building and refurbish it, or replace it. There has been a lot of debate

about the present building and there are mixed feelings about it, but it is of

architectural importance, is a gateway site for the city and is in a conservation

area. In addition, the space around the building is protected and contains very significant archaeology".

A year later, in February 2002, city council planners duly recommended that the building be demolished to make way for a "prestigious" new development. They have made it known thay they would favour a three or four-storey building that would create jobs, such as a hotel, leisure or conference centre. It had emerged that Cheshire Police would be relocating to their new purpose-built headquarters at Woodford Business Park in Winsford at the end of 2003 and the site would become available for redevelopment soon after.

Even those self-appointed guardians of our city's heritage, the Chester Civic Trust, who, just a few years ago, thought it would be a good idea to build a bunch of glass-and-steel office tower blocks at the Old Port, to "provide a 'gateway' to the city and be a commercially stimulating centrepiece

for the revival of the area" decided not to campaign for the preservation of the building. They were, however, "cautious" about the prospect of outright demolition and were said to recognise the value of a building "so clearly of its time"- and suggested that a "sensitive refurbishment" may have been more appropriate. Even those self-appointed guardians of our city's heritage, the Chester Civic Trust, who, just a few years ago, thought it would be a good idea to build a bunch of glass-and-steel office tower blocks at the Old Port, to "provide a 'gateway' to the city and be a commercially stimulating centrepiece

for the revival of the area" decided not to campaign for the preservation of the building. They were, however, "cautious" about the prospect of outright demolition and were said to recognise the value of a building "so clearly of its time"- and suggested that a "sensitive refurbishment" may have been more appropriate.

Right and below left: these early 'artist's impressions' were how the HQ Building was first presented to the public. The final design, below right, was, in the opinion of many, a great improvement.

In this, they were as successful as they were trying to save the Militia Buildings, the police HQ's predecessor. But then,

their national organisation did give the thing an award, "for its outstanding architectural contribution to the local scene" back in 1969.

Above we present a final photograph of the half-demolished Police HQ in October 2006- and (right and below) some first views of the brave new building by Liberty Properties PLC now (Summer 2008) rapidly rising as its replacement.

This enormous new structure, to be known as 'HQ', was to feature a hotel, conference centre, offices and apartments as well as bars and restaurants set around an internal circular public piazza.

But then, in the Summer of 2009, a row broke out when it was proposed by the leadership of the newly-formed Cheshire West and Chester Council ( a new creation formed after the demise of the old Chester City and Cheshire County Councils) that County Hall, home of the County Council since 1957, should be sold to the rapidly-expanding Chester University for £10 million and that the council should take up offices within the newly-built HQ Building instead. The details may be found here.

Novemember 2009: Our council have now acquired all of the office space within the HQ development. An article on the Hill Dickinson website explains all. (We were amused by the brief final sentence in this piece, "The council advised itself").

The Minor Religious Houses

In Roman times, all of the land we see ahead of us between here and the distant towers on the NW corner of the City Walls was part of the civil settlement, lying west of the Legionary fortress and adjacent to the quays situated along the banks of a much more substantial river than we see today. In its southern part have been discovered the remains of several substantial houses and north of these, a small tributary river once ran westwards to join the Dee but this had been drained and partially infilled during Roman times- although the land remained low-lying and boggy for centuries to come. In Roman times, all of the land we see ahead of us between here and the distant towers on the NW corner of the City Walls was part of the civil settlement, lying west of the Legionary fortress and adjacent to the quays situated along the banks of a much more substantial river than we see today. In its southern part have been discovered the remains of several substantial houses and north of these, a small tributary river once ran westwards to join the Dee but this had been drained and partially infilled during Roman times- although the land remained low-lying and boggy for centuries to come.

Little is known of the area in the centuries following the withdrawal of the Legions but it seems have been relatively little used. The River Dee, however, was undergoing major changes as falling sea levels and silting resulted in the once-busy harbour becoming landlocked and the large tract of land that now lies between the river and the city- the Roodee we know today- started to be formed.

The other major change to the area was the creation of the City Wall upon which we now stand- which, to the surprise of many, did not actually exist on this side of the city until the early 12th century- to enclose this area within the defended circuit. This did not apparently result in any great immediate outburst of urbanisation, however, and most of the great area between the Castle and the North Wall long remained open land- known as The Crofts- and was utilised as smallholdings, gardens and orchards- land of relatively little value that could freely be granted for the founding of religious houses. Which, as we will learn, between the mid-12th to mid-13th centuries, is exactly what happened. The other major change to the area was the creation of the City Wall upon which we now stand- which, to the surprise of many, did not actually exist on this side of the city until the early 12th century- to enclose this area within the defended circuit. This did not apparently result in any great immediate outburst of urbanisation, however, and most of the great area between the Castle and the North Wall long remained open land- known as The Crofts- and was utilised as smallholdings, gardens and orchards- land of relatively little value that could freely be granted for the founding of religious houses. Which, as we will learn, between the mid-12th to mid-13th centuries, is exactly what happened.

In Roman times, the ground on this side of the city west of the present day Inner Ring Road sloped sharply westwards down to the river bank and this slope was eventually cut into three terraces to produce level platforms for buildings and agriculture. The lowest of these terraces was fronted by the massive stone retaining wall which formed the Roman quayside, parts of which may still be seen on the Roodee today (see photograph below).

The City Wall was eventually built on top of this lower terrace, about five metres back from its edge. Immediately north of the site, however, the quay ran across the mouth of the small drained river valley, presumably in the form of a causeway, isolating the valley from the river. Behind the causeway there was only soft ground, unsuitable for erecting a large wall on, so consequently the wall deviates westward and was built close to the quay edge- probably on top of the causeway itself.

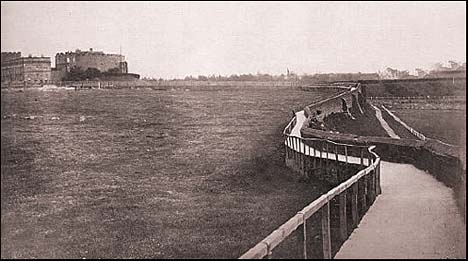

The erection of this great wall produced a barrier at the foot of the hillside against which deposits washed down from the slopes above could accumulate, a process that continued from the 12th century right through to fairly recent times. The result is that the entire sloping hillside has disappeared beneath around five metres of accumulated deposits and the ground level we walk on today is now more or less level with the top of the wall. Looking over the parapet at the drop below (see the old photograph below) and the City Wall's great supporting buttresses makes the situation dramatically clear and explains why the walls appear so different on this side of the city to those elsewhere in the circuit.

The last traces of the boggy former tributary valley were filled in around 1827 by the construction of the great embankment to carry the approach road to the Grosvenor Bridge. The last traces of the boggy former tributary valley were filled in around 1827 by the construction of the great embankment to carry the approach road to the Grosvenor Bridge.

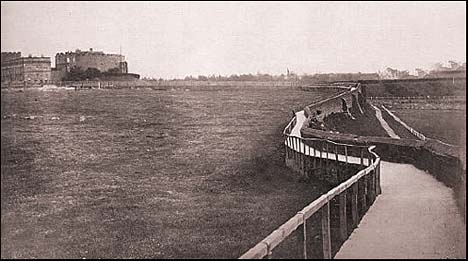

Left: Even 150 or so years ago, things hereabouts looked very different from today, as you see in these interesting photographs, showing the Roodee much as we know it, but, above, Nun's Road was an uneven grassy track snaking its way along the top of the wall. Below, earlier- and stranger- still, before villas started to appear, there is nothing but open land from the West Wall to the Castle.

Commencing in the 1150s most of the Crofts were to be occupied by the houses of religious communities. Nontheless, much of the land remained unbuilt-upon, serving in its ancient role as the fields and vegetable gardens of the monks and nuns. After the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s and 40s, their estates were gradually split up and developed- the final section, Lady Barrow's Hey, at the far end of the road, as late as 1963, when the site was occupied by the extension of the Chester Royal Infirmary (which we will visit soon)- which itself was demolished in 1998 to make way for new housing.

Passing the boarded-off site of the recently-demolished Police HQ, we

find ourselves

standing

in Nun's

Road,

so

called

because

it

occupies

part

of

the

lands

of

the

Benedictine Nunnery

of St. Mary's which

stood

on

the

site which was later occupied by the

Police

HQ

from

Saxon

times

until

the

reign

of

Henry

VIII- when, in

1537,

along

with

the

neighbouring

houses

of

the

Black,

White

and

Greyfriars,

it

was

dissolved

and

the

nuns

cast

out

to

fend

for

themselves. (it

was,

however,

recorded

that

the

Prioress

and

eleven

other

nuns

were

given

pensions

which

they

were

still

receiving

21

years

later,

in

1556). Passing the boarded-off site of the recently-demolished Police HQ, we

find ourselves

standing

in Nun's

Road,

so

called

because

it

occupies

part

of

the

lands

of

the

Benedictine Nunnery

of St. Mary's which

stood

on

the

site which was later occupied by the

Police

HQ

from

Saxon

times

until

the

reign

of

Henry

VIII- when, in

1537,

along

with

the

neighbouring

houses

of

the

Black,

White

and

Greyfriars,

it

was

dissolved

and

the

nuns

cast

out

to

fend

for

themselves. (it

was,

however,

recorded

that

the

Prioress

and

eleven

other

nuns

were

given

pensions

which

they

were

still

receiving

21

years

later,

in

1556).

Their

estate and

buildings

survived,

and in 1542 were granted to Urian Brereton and became the Chester house of the Breretons of Handforth for the next hundred years. By the time of the Civil war in 1642-6, this was

the

home

of Sir

William

Brereton- at least until he became leader of the Cheshire Parliamentary forces- early in 1643 the buildings were attacked and pillaged by Welsh soldiers who formed part of the Chester garrison loyal to the King.

Norman

Tucker's

stirring

novel

of

1949, Master

of

the

Field (unfortunately

no

longer

in

print but well worth trying to find)

dramatically

recreates

Sir

William's

home

as

it

was

at

this

time,

as

well

as

being

a powerful

evocation

of

the

stirring

event

during

the

long

and

bloody Siege

of

Chester,

when,

along

with

many

other

buildings

within

and

without

the

walls,

the

Priory

buildings

were largely

destroyed and

their remains left to fall into decay.

The site was finally cleared and grassed over to form a fitting approach to the newly rebuilt Castle and today

not

a trace

remains

above

ground. An

archway

from

the

old

priory

was,

however,

re-erected

to form a 'folly' at St. John's Priory, a private house that once stood in the churchyard at St. John's Church and was the home of the mother of the 'English Opium Eater', Thomas De Quincey.

When that house was removed, the arch was transferred to Grosvenor

Park,

where

it

may

still

be

seen today

(together

with

an

arch

from St. Bridget's

Church which

stood

for a thousand years in

Lower

Bridge

Street before being demolished to make way for Grosvenor Street,

and

the

ancient Shipgate,

which

we

learned

about

earlier

in

our

walk). Some of the old convent's stones were also incorporated into the rebuilt porch of the church of St. Mary-Within-the-Walls, next to the Castle. It was recorded that, when the site was cleared, many bones were uncovered, together with fragments of doors and windows and other masonry- some of Norman style others in the richer manner of the 15th century, painted and gilt-encrusted. When that house was removed, the arch was transferred to Grosvenor

Park,

where

it

may

still

be

seen today

(together

with

an

arch

from St. Bridget's

Church which

stood

for a thousand years in

Lower

Bridge

Street before being demolished to make way for Grosvenor Street,

and

the

ancient Shipgate,

which

we

learned

about

earlier

in

our

walk). Some of the old convent's stones were also incorporated into the rebuilt porch of the church of St. Mary-Within-the-Walls, next to the Castle. It was recorded that, when the site was cleared, many bones were uncovered, together with fragments of doors and windows and other masonry- some of Norman style others in the richer manner of the 15th century, painted and gilt-encrusted.

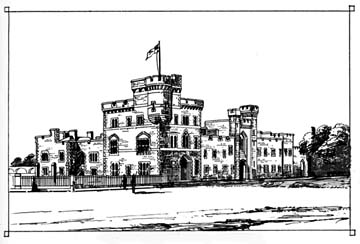

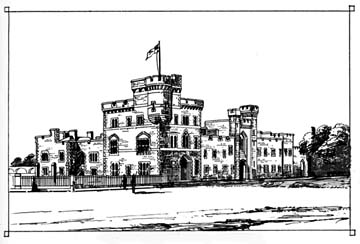

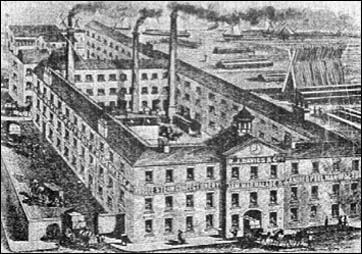

Left: Guarded by the Javelin Men, the coach carrying the Judge and High Sheriff to the Chester Assizes at the Castle pass before the impressive Militia Buildings which stood where the new HQ development is now. The inner courtyard of the Militia Buildings may be seen below. Another photograph of the Javelin Men may be seen on our Chester Castle pages and they and the Militia Buildings may be seen again in our Chris Langford gallery.

As previously mentioned, the construction of later buildings on the site have resulted in the probable complete destruction of the remains of the nun's church and its cloister. Much else, including the outer court and the 16th century mansion of the Breretons still survive beneath the formerly-landscaped area to the north west of the site. Will they be properly investigated this time- even, who knows, preserved in situ- before the new development takes place?

Today's developers allow, and may even help to fund excavations, but frequently commercial pressure to build on ancient sites, especially those incorporating basements or underground car parks, often allow archaeologists only a brief time to complete their work before the remains are obliterated. Dennis Petch's terse description of the destruction of a great Roman bath house on the site of the Grosvenor Shopping Precinct is a classic example. Future generations will doubtless think us very foolish.

The

Nuns

of

St.

Mary's originated

as

a poor

order,

and

indeed

for a long period had

great

difficulty

making

ends

meet.

Later,

Royal

patronage

and

liberal

bequests

ensured

the

nunnery

became

very

rich, owning property in most of the streets of Chester as well as land in Cheshire, Lancashire and even as far as South Wales.

Though they are centuries dead and the stones of their church scattered and lost, a part of them remains with us today, for, around the year 1425 was composed within the walls of the nunnery the beautiful Carol (or Song) of the Nuns of Chester which forms part of the repertoire of choirs throughout the world and is widely available in numerous recordings. Go

here to

learn

more

about

them.

Passing along Nun's Road, we soon come to a narrow lane on the right bearing the evocative name of Blackfriars. This marks the approximate boundary between the precincts of the nuns of St. Mary's and the Dominican Friary, whose lands extended from here almost as far as Watergate Street. Passing along Nun's Road, we soon come to a narrow lane on the right bearing the evocative name of Blackfriars. This marks the approximate boundary between the precincts of the nuns of St. Mary's and the Dominican Friary, whose lands extended from here almost as far as Watergate Street.

The Dominicans, or Black Friars, were the first to establish themselves in Chester, founding their house here around 1236 (only fifty years after the first English Dominical foundation, at Oxford) and they dedicated their church to St. Nicolas. Documents show that a previous chapel, also dedicated to that saint, already existed on the land they acquired and they presumably used it before their own church was completed. By 1276, work had progressed so far that the monks built a pipeline from the natural springs (that had been in use since Roman times) at Boughton, 2 kilometers away, to supply their domestic quarters and kitchens with fresh water. The monastery was completed sufficiently for the Provincial Chapter of the Dominican order to be conducted here over three days in 1312.

Their church was rebuilt and expanded at least three times during the three centuries of occupation of the site and the last, and grandest, was still incomplete when the Friary was dissolved. During the decade before the Dissolution, the monks made many leases of land, perhaps in an attempt to make provision for themselves when the end came or possibly in an optimistic attempt to raise funds to complete their ambitious building programme in the unlikely event of their house being spared. One such was to Ralph Waryn in May 1537 and included "lands, gardens and orchards with two old chambers and a ruinous building, with the surrounding stone walls on the east and north of the house and church" and another, a mere two months before the surrender, to Richard Hope for "three houses lying together at the lower end of the church with the parish of Saint Martin".

All was to no avail however, and the Dominicans, together with the other two Chester friaries, surrendered their house to Henry VIII's commissioners on 15th August 1538. An inventory of the buildings and contents were made which, aside from the stained glass in the windows and the lead on the roofs, found "little of value"- the monks having presumably disposed of all vestments, plate and other valuables bore the inevitable befell them. All was to no avail however, and the Dominicans, together with the other two Chester friaries, surrendered their house to Henry VIII's commissioners on 15th August 1538. An inventory of the buildings and contents were made which, aside from the stained glass in the windows and the lead on the roofs, found "little of value"- the monks having presumably disposed of all vestments, plate and other valuables bore the inevitable befell them.

Right: the inner courtyard of the vanished Militia Buldings which once stood where the brand-new HQ development is now.

The estate was leased to Thomas Smythe and Richarde Sneyde who (or perhaps their successors) eventually 'asset stripped' it, demolishing the buildings and disposing of the finely-cut blocks of masonry and the fixtures and fittings for use elsewhere. Their demolition and levelling of the site was so thorough that subsequent archaeological excavation (which was much more thorough than at St. Mary's Convent) found very little masonry surviving above the foundations- and even much of that had been dug out.

Pits discovered on the site were used for lead smelting, probably from the recovery of lead from the monastery's roofs and windows. There were some survivals, however, at least for a while. One early 17th century record, referring to the church, stated, "it stood in St. Nicolas Street and belonged to the Black Friars, and the great gate is yet remaining in the wall on the west side about the middle of the street". This gate may be seen on John Speed's 1610 map of Chester.

Some fragments survived for much longer- in his 1856 work, The Stranger's Guide to Chester, Thomas Hughes, after a description of the Roodee, wrote, "we will now return to the Walls, noticing as we pass through the Water Gate, to the right, the remains of the wall of the Black Friars' Monastery". Some fragments survived for much longer- in his 1856 work, The Stranger's Guide to Chester, Thomas Hughes, after a description of the Roodee, wrote, "we will now return to the Walls, noticing as we pass through the Water Gate, to the right, the remains of the wall of the Black Friars' Monastery".

In the course of time, the estate was split up and developed but many of these modern property boundaries are aligned on the long-vanished Friary church and its associated buildings. We shall learn a little of the third of the monasteries, that of the Franciscans, that once existed on this side of the city- and also of a further religious community, the Carmelite White Friars- when we reach the Watergate.

Looking

over

the

parapet

here

we

see

the

great

buttresses

which

support

the

wall

all

along

this

side

together

with

the

immense

weight

of

earth

and

masonry

behind. If

you

look

at

the

triangular

coping

atop

this

stretch

of

wall,

you

will

see

a number

of

gaps-

unnoticed

by

virtually

all

who

pass

by-

but

in

fact

truly

remarkable

survivors

of

a savage

age:

original

relics

of

Chester's

ancient

battlements,

representing

the

lower

part

of

the crenelles or embrasures-

the

openings

through

which

soldiers

discharged

their

weapons

before

retiring

behind

the

higher

parts,

the merlons,

to

reload.

At

that

time

of

course,

these

battlements

stood

much

higher

relative

to

the

walkway

and

would

have

afforded

considerable

protection.

The

Roodee

From

this

point

until

we

reach

the Watergate,

below

us

stretches

the

beautiful

65-acre Roodee,

the

"sweet

rood

of

Chester"

(Gascoigne

1575)-

whose

curious

name

derives

from

the

Saxon Rood-

a

cross

or

crucifix

and

the

Norse

suffix Eye-

meaning

an

island,

thus

literally

'The

Island

of

the

Cross'.

In

Saxon

times,

the

waters

of

the

Dee

covered

the

whole

of

this

area

with

the

exception

of

a

small

island

upon

which

stood

a

stone

cross,

the

stump

of

which

you

may

still

see

in

the

middle

of

the

racecourse

today.

It

seems,

however,

to

have

been

moved

during

the

last

150

years-

Batenham's

map

of

1823

shows

it

situated

further

north

on

the

Roodee,

opposite

the

end

of

Greyfriars,

and

Hemingway,

thirteen

years

later,

records

that

it

was

placed "to

mark

the

boundary

of

the

land

there

belonging

to

the

Nuns

of

Chester", which

confirms

its

former

location.

Tradition

tells

us

that,

around

AD946,

the

cross

was

erected

over

a

statue

of

the

Virgin

Mary,

which

floated

to

Chester

up

the

river,

having

been

ejected

from Hawarden

Church for

falling

on-

and

killing-

the

Lady

Trawst,

wife

of

Sytsylht

(a

nobleman

and

governor

of

Hawarden

Castle)

whilst

she

was

at

prayer

asking

for

rain-

there

being

at

the

time

a

severe

drought.

Her

Lord

was

outraged,

assembled

a

jury,

recorded

as:

Hincot

of

Hancot,

Span

of

Mancot,

Leech

and

Leach,

and

Cumberbeach;

Peet

and

Pate,

with

Corbin

of

the

Gate,

Milling

and

Hughet,

with

Gill

and

Pughet,

- and

put

the

statue

on

trial

for

murder!

She

was

convicted-

also

being

found

guilty

of

not

answering

her

accusers-

and

condemned

to

be

hanged.

One

juryman

opposed

that,

saying

that,

as

they

wanted

rain,

it

would

be

best

to drown her.

Another

argued

that,

as

she

was

'Holy

Rood',

they

had

no

right

to

kill

her,

but

he

suggested

that

they

lay

her

on

the

sands

on

the

river

below

Hawarden

Castle,

that

God

might

do

what

he

would

with

her.

This

they

did,

and

the

tide

took

her

down

river

to

Chester,

where

the

inhabitants

found

her,

"dead

and

drowned"

upon

which

they

buried

her

where

she

was

found

and

raised

over

her

a

stone

cross,

which

is

said

to

have

borne

the

following

inscription:

The

Jews

their

God

did

crucify,

The

Hardener's

theirs

did

drown,

Cause

with

their

wants

she'd

not

comply;

And

lies

under

this

cold

ground.

Even

earlier,

in

Roman

times,

the

river,

which

was

then

much

wider

and

deeper,

flowed

right

up

to

what

is

now

the

base

of

the

medieval

city

wall.

Remember

that

the

Roman

wall

was

set

much

further

back

than

this,

running

along

the

line

of

the

present

inner

ring

road,

between St.

Martin's

Gate and

the Newgate-

the

present

wall

resulting

from

the

Saxon

expansion

of

the

fortress

in

the

10th

century.

If

you

walk

down

the

steps

to

the

racecourse

and

grub

about

behind

a

lot

of

brambles,

debris

and

portable

buildings,

you

will

be

rewarded

with

the

sight

of

the

massive

stones

of

what was once the Roman

harbour

wall,

(right)

where

once

war

gallies

tied

up

and

the

trading

ships

of

the

empire

discharged

their

cargoes

of

wine

and

spices.

Although

only

a

few

courses

of

these

stones

show

above

ground,

they

extend

for at

least another

15

feet

underground

for

much

of

the

length

of

the

wall

between

here

and

the Watergate,

with

traces

of

groin

walls

running

off

at

right

angles.

(Investigation

beyond

this

depth

was

curtailed

because

of

flooding

by

the

water

which

still

endures

below

ground

level). If

you

walk

down

the

steps

to

the

racecourse

and

grub

about

behind

a

lot

of

brambles,

debris

and

portable

buildings,

you

will

be

rewarded

with

the

sight

of

the

massive

stones

of

what was once the Roman

harbour

wall,

(right)

where

once

war

gallies

tied

up

and

the

trading

ships

of

the

empire

discharged

their

cargoes

of

wine

and

spices.

Although

only

a

few

courses

of

these

stones

show

above

ground,

they

extend

for at

least another

15

feet

underground

for

much

of

the

length

of

the

wall

between

here

and

the Watergate,

with

traces

of

groin

walls

running

off

at

right

angles.

(Investigation

beyond

this

depth

was

curtailed

because

of

flooding

by

the

water

which

still

endures

below

ground

level).

The

visitor

passing

by

at

pavement

level

is

told

a

little

of

the

vanished

Roman

harbour

on

one

of

a

series

of

information

panels

which

of

recent

times

have

sprouted

at

strategic

locations

around

the

walls-

but

it

is

nontheless

a shame

that

this

most

evocative

of

relics

of

the

founders

of

our

city

should

currently

be

so

poorly

presented.

Roman Cemetery

It is strange that, so close to the bustle of the old harbour, a cemetery also existed here in those far-off Roman times and a number of burials have been discovered along the grassy embankment beneath the City Wall. A contributor to The Cheshire Sheaf, one F. H. W., told of a number of these in that journal in 1882- at the same time giving us a vivid impression of the exceedingly casual attitude with which ancient finds such as this were treated at the time- "The first interment we are acquainted with occurred near here in the ground under the south, end of the Dee Stands, I cannot furnish particulars, but have been told that a small, though perfect, Samian-ware vessel now in the collection of Mr. Frederick Potts was taken from this tomb.

In repairing the steps above-mentioned several years ago, the bones of a young person were found in the ground beneath: indeed the grave was described to me as being partly situated in an oblique position, and under the Walls; also that a Roman coin (second brass I think) had been deposited with the body. Mr. Shrubsole possesses the lower jawbone of the skeleton. At the same spot, only lower down the bank, a third grave was uncovered; but in this case the remains were surrounded by a coffin-like cist composed of small squared pieces of red sandstone.

The next to be noticed was found on the top of this bank in 1865, between the first and second buttresses, counting from the steps referred to. It lay at about a foot below the surface, and was composed of the ordinary red clay Roman roofing tiles (tegulae). A silver denarius of the Emperor Otho accompanied the skeleton, which was almost entire, and in its original position.

At no great distance from this, an interment was met with which may be considered as one of the most interesting yet discovered at Chester; from the circumstance that a head-stone was disinterred at the same time, which there is every reason to believe once marked the grave. This occurred in June 1874, when a cutting was made across the Roodeye, in order to form the intercepting sewer from Boughton, and running under the County Gaol. I shal here give one or two quotations from the description of Mr G W Shrubsole, who was present after its discovery:-

"The excavation commenced near the Castle, along the south face of the little-Roodee. On passing the angle of the Walls, clay and rock were found, and when the Grosvenor Bridge embankment was reached, tunnelling through rock was resorted to. Reaching the Roodee- proper, an open cutting was begun, and continued across to the Watergate. Soon after passing the Grosvenor Bridge embankment the workmen came upon a large flat stone, which proved to have an inscription of the Roman age."

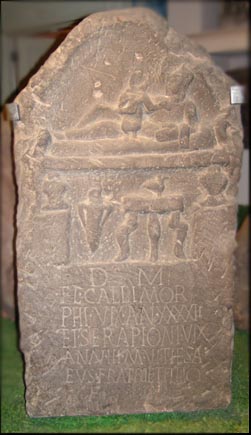

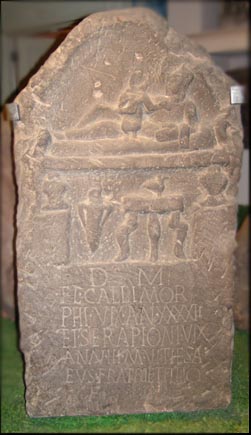

This slab, formed of the ordinary red sandstone of the district, is inscribed in perfectly legible characters—

D. M.

F. L. CALLIMOR

PHI . VIX . AN . XXXXIi .

ET . SERAPIONI . VIX .

ANN . III . M. VI . T . HE . SA .

EVS . FRATRI . ET . FILIO .

F. C. |

Which has been thus translated by Mr Hughes,— "To the divine shades of Flavius Lucius Callimorphus, who lived 42 years, and to Serapion, who lived 3 years and 6 months. Thesa caused this to be erected to her Brother and his Son."

As is frequently the case in monuments of this class, the upper portion is obtusely pointed, and has a species of tympanum or recessed compartment, with a carving in relief, representing Callimorphus on a couch in a recumbent posture, with his son Serapion resting on his lap. Near the side of this couch or bed is a small, gracefully formed stand; and, to the left of this, an unmistakeable amphora. Height of the slab, 4 feet 2 inches; width, 2 feet 3 inches; and average thickness about 6 inches. As is frequently the case in monuments of this class, the upper portion is obtusely pointed, and has a species of tympanum or recessed compartment, with a carving in relief, representing Callimorphus on a couch in a recumbent posture, with his son Serapion resting on his lap. Near the side of this couch or bed is a small, gracefully formed stand; and, to the left of this, an unmistakeable amphora. Height of the slab, 4 feet 2 inches; width, 2 feet 3 inches; and average thickness about 6 inches.

Right: the gravestone of Callimorphus and Serapion, resting now in the wonderful Roman Stones Gallery in the Grosvenor Museum.

I again quote Mr. Shrubsole's remarks: "The Inscribed Stone was found between the second and third buttresses of the Walls, counting from the Grosvenor Road, and 40 feet west from the Walls, and within the ring of posts which spans the Roodee, but 6 feet from the outer line. It narrowly escaped being broken up to facilitate its removal from the trench. The grave had been dug nearly east and west; the head was towards the river, the feet to the Walls. The excavation cut through only a portion of the grave. The only bones I saw were two human skulls, one of them larger than the other, and some belonging to the upper part of the body. Other bones could be seen protruding on the east side of the cutting, and were not disturbed by me. I declined the gift of them, and in the filling in of the trench they were deposited close to their former resting place. The finding of a gold ring and a Roman coin among the filled-in rubbish composing the grave, is quite in accordance with what we should expect to find at a Roman burial. With regard to the ring, I ought to say that I never saw it. It was described to me as large, and massive in character. The man who found it left the city the next day. The Roman coin I examined- it was a second brass of Domitian in poor condition.

Passing again over the bank in May 1881, 1 noticed, washed bare by the rain, some osseous substance protruding from the soil within a foot or so to the south of the third buttress counting from the steps below Black Friars. Being well aware of the nature of the ground, I suspected that it might be a human skull; and on removal with the point of my stick it proved to be so. A subsequent examination revealed the rest of the skeleton, which lay with its head to the north and the feet to the south, about a foot from and parallel with the Walls.

On re-visiting the spot in the June of the same year another rounded object, from which the soil had been denuded, was presented to my view. This I at first mistook for the polished surface of a boulder, but soon recognised its real nature. The body had been laid in the same position as the last, and parallel with the Walls, only lower down, and a little further south. I searched carefully among the earth from within and around each skull, in the hope of finding a coin- Charon's toll- but did not succeed. And in neither case did I meet with any traces of a coffin, or with any of the objects usually found in such situations. The two skulls, the first of which came all to pieces, I have restored as far as possible and placed in the Museum of the Chester Archaeological Society [now the Grosvenor Museum]. The skull from the upper grave was broken in through the right side (which was exposed) before I saw it. The second is almost perfect; yet so great is the contempt with which the lower classes regard such matters, that had I not removed them they would, possibly shortly afterwards, have been utilised as footballs on the green sward below”.

Many more fascinating and well-preserved Roman gravestones are displayed alongside that of Callimorphus and Serapion in the Grosvenor Museum- a visit to which should be considered essential when you come to Chester. Most of these were, remarkably, discovered embedded within the North City Wall when repairs were being undertaken there in the nineteenth century. Learn more about them here.

While

you

are

down

here, walking upon the Roodee,

look

out

for

the

square

stone

column

surmounted

by

a

railed

enclosure,

known

as

the Judge's

Chair-

a

relic

of

18th

century

racing

days.

This

column

is

the

surviving

one

of

a

pair,

the

other

having

stood

directly

opposite,

on

the

far

side

of

the

course.

Around

1615,

the

Roodee

was

described

as "a

very

delightful

meadow

place,

used

for

a

cow

pasture

in

the

summertime;

and

all

the

year

for

a

wholesome

and

pleasant

walk

by

the

side

of

the

Dee,

and

for

recreations

of

shooting,

bowling

and

such

other

exercises

as

are

performed

at

certain

times

by

men;

and

by

running

horses

in

presence

and

view

of

the

mayor

of

the

city

and

his

brethren;

with

such

other

lords,

knights,

ladies

and

gentlemen

as

please

at

these

times,

to

accompany

them

for

that

view".

In

1636, "The

mayor

caused

the

durt

of

many

foule

lanes

in

Chester

to

be

carried

to

make

a

banke

to

enlarge

the

Roodey

and

let

shipps

in.

It

cost

about

£100".

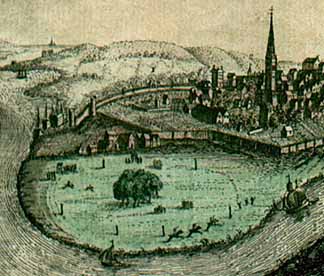

Here we

see

a

view

of

the

Roodee-

a

small

detail

from

this view

of

Chester-

which

appeared

in

the London

Magazine in

1753.

Sailing

ships

navigate

the River

Dee and

beyond

the Watertower at

the

angle

of

the

city

walls,

open

land

stretches

as

far

as

the

eye

can

see.

Within

the

walls,

too,

are

large

areas

of

cultivated

fields.

(Just

eight

years

after

this

view

was

published,

the Infirmary would

be

built

on

part

of

these). On

the

right

rises

the

tall

spire

of Holy Trinity Chuch in Watergate Street. Here we

see

a

view

of

the

Roodee-

a

small

detail

from

this view

of

Chester-

which

appeared

in

the London

Magazine in

1753.

Sailing

ships

navigate

the River

Dee and

beyond

the Watertower at

the

angle

of

the

city

walls,

open

land

stretches

as

far

as

the

eye

can

see.

Within

the

walls,

too,

are

large

areas

of

cultivated

fields.

(Just

eight

years

after

this

view

was

published,

the Infirmary would

be

built

on

part

of

these). On

the

right

rises

the

tall

spire

of Holy Trinity Chuch in Watergate Street.

As the Dee continued to silt up, the area of permanently dry land increased and was declared to be part of the parish of this church, but, doubtless to the irritation of the clergy, could not be tithed as it was deemed to be land reclaimed from the sea. On

the

Roodee

itself,

a

horserace

is

in

progress.

Notice

the

apparent

lack

of

any

facilities

other

than

the

crude

marker

posts

erected

to

help

jockeys

navigate

the

course-

and this

despite

the

fact

that

organised

horse

races

had,

by

this

time,

been

held

here

for

well

over

200

years.

1753,

when

this

picture

appeared,

was,

interestingly,

the

year

that

a

permanent

racecourse

was

first

established

at Newmarket.

All of these interesting features may be better seen in a similar image of the Roodee, a detail from Nathaniel Buck's 1728 view of Chester.

The

Roodee's

rural

nature

survived

into

living

memory.

Writing

in

the

local

press

in

1999,

Mrs

J

Moore

recalled,

"I've

been

reminiscing

about

the

days

of

my

youth

when

cows

and

sheep

grazed

on

the

middle

of

the

big

Roodee

when

the

grass

was

higher

than

me.

It

was

cows

in

summer

and

sheep

in

winter.

I

can't

remember

when

they

started

to

cut

the

grass

by

machine-

some

time

after

the

war,

I

think. I

recall

cows

coming

up

and

down

Lower

Bridge

Street

on

their

way

to

the

cattle

market

at

Gorse

Stacks.

Tuesdays

and

Thursdays

were

days

when,

if

you

had

any

sense,

you

kept

away

from

the

Cow

Lane

Bridge

and

Brook

Street

area

unless

you

were

at

ease

with

cows,

bulls,

sheep,

pigs

etc.

The

cows

were

the

worst

(unless

the

occasional

bull

escaped)

They

went

into

shops,

and

so

did

the

public

trying

to

dodge

them-

hopefully

not

the

same

shops!

My

sister

worked

in

Brook

Street

and

remembered

many

a

heart-stopping

occasion.

At

least,

she

said,

in

Brook

Street

you

could

avoid

them,

but

if

you

met

the

herds

on

Cow

Lane

Bridge,

there

was

nowhere

to

hide!"

The Roodee Workhouse

In centuries gone by, each parish was responsible for the welfare of its poor and destitute. By the start of the 18th century, a system of Poor Houses was introduced, one for each parish. The records of St Mary’s Parish show that the appointed Master of its Poor House was expected to abide by many rules, just a few examples being: In centuries gone by, each parish was responsible for the welfare of its poor and destitute. By the start of the 18th century, a system of Poor Houses was introduced, one for each parish. The records of St Mary’s Parish show that the appointed Master of its Poor House was expected to abide by many rules, just a few examples being:

“He cause the house to be swept from top to bottom every morn and washed once a week at the least.”

“A cloth be laid at every meal and the Poor sit at table in a decent manner and that grace be constantly said.”

“Neither children nor others go abroad on Sundays, but continue together in the House and read the Holy Scriptures or other good book.”

How far the reality corresponded with these ideals we shall never know. Much would depend of course on the type of person the Master was. Despite the regimented way of life, it is possible that the “inmates” were in fact better off than some of those parishioners struggling to make a living on the ‘outside’. They could at least expect three square meals a day and there is a record in St Oswald’s Parish of a woman being employed to teach the children of the Poor House to read.

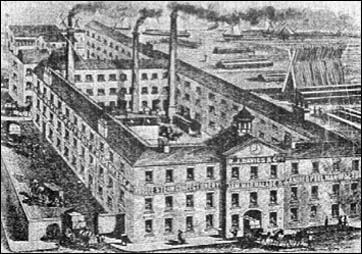

With the cost of caring for the increasing numbers of poor becoming a great burden upon the individual parishes, a decision was made in 1757 to set up a general Workhouse or House of Industry for the whole of the city. Work began in 1758 on a “four-square rectangular brick building round a courtyard, at the north-west extremity of the Roodee,” and for over a century this building played a large part in the lives of many Cestrians. Not far from this was The Tower Field, of which in 1836 Hemingway wrote that it had "recently been rented by the guardians of the poor by the cultivation of which, by spade husbandry, able-bodied paupers were very properly and advantagiously employed". This Tower Field is known to us today as Water Tower Gardens, a pleasant little park, complete with tennis courts and a popular bowling green.

The Workhouse survived here by the Roodee until the late 1870s, when the Board of Guardians, formed in 1869, built a new workhouse in Hoole Lane (which later became the City Hospital before being demolished in the 1970s to make way for new housing. Only its chapel and graveyard survive today).

After the city’s paupers left, the Roodee Workhouse was put to use as a confectionery works by the Cheshire Preserving Company and it was apparently demolished between 1902 and 1906.

Go

on

to part

II of

our

exploration

of

Chester's

beautiful

Roodee...

Curiosities

from

Chester's

History

no. 22 Curiosities

from

Chester's

History

no. 22

- 1659

Sir

George

Booth,

on

hearing

that

the

Parliamentarian

General

Lambert

was

appoaching

the

city,

marched

on

him

with

3,000

troops

and

engaged

him

in

battle

at

Northwich,

where

Booth

was

defeated.

Lambert

then

carried

on

to

Chester.

As

a

punishment,

Parliament

dissolved

the

Chester

Corporation

and

ordered

that

the

city

should

no

longer

be

a

separate

county.

However,

the

Parliamentarians

did

not

hold

power

long

enough

to

enforce

the

order.

- 1660

Parliament

invites Charles

II (1630-1685) to

return

to

England.

The

communion

table

from

St.Mary's-on-the-Hill

was

found

to

be

missing,

so

6d

was

spent

on

a

warrant

to

search

for

it

and

4d

spent

on

constables

"in

going

about

to

search

for

the

table". Samuel

Pepys starts

to

write

his

diary.

1661

Coronation

of

King

Charles

II.

No

Michaelmas

Fair

held

in

Chester

this

year

because

of

the

Plague. Daniel

Defoe born (-1731) . 1663

Turnpike

roads

introduced

into

England.

First

golden

guineas

coined-

and the Hearth

Tax was introduced in order to support the household of Charles II. 1664

The

'Bear

and

Billet

Inn'

in

Lower

Bridge

Street

was

built-

or

rebuilt-

this

year.

Standing

in

its

own

grounds,

it

was

originally

the

town

house

of

the

Talbot

family-

the Earls

of

Shrewsbury-

who

were

Sergeants

of

the

nearby Bridgegate.

They

later

leased

it

to

an

innkeeper,

on

condition

that

a

suite

of

rooms

was

always

kept

available

for

the

Earl

and

his

family.

It remains a fine pub to this day. (Go here to

read

about

some

more

old

Chester

pubs)

Charles

II

granted

the

city

a

new

Charter.

1669

The

spire

of

St.

Peter's,

at

the

High

Cross,

was

found

to

be

in

a

dangerous

condition,

and

taken

down.

- 1677

Mr

Andrew

Yarranton

took

a

survey

of

the River

Dee and

published

the

results

in

a

book

called

'England's

Improvement

by

Sea

and

Land'.

He

made

a

proposal

to

the

Duke

of

York

to

reclaim

a

large

area

of

land

from

the

sea

by

making

a

new

channel

which

would

carry

the

water

to

the

walls

of

Chester.

However,

no

interest

was

aroused

in

his

proposals,

so

he

abandoned

the

scheme.

The Roodee, 450 Years of Racing in Chester by R M Bevan. Available from Cheshire Books Direct www.cc-publishing.co.uk

Top

of

Page | Site

Index | Site

Front

Door | Chester

Stroll

Introduction | Grosvenor

Bridge | Roodee

part

II

|

Even those self-appointed guardians of our city's heritage, the

Even those self-appointed guardians of our city's heritage, the  In Roman times, all of the land we see ahead of us between here and the distant

In Roman times, all of the land we see ahead of us between here and the distant  The other major change to the area was the creation of the City Wall upon which we now stand- which, to the surprise of many, did not actually exist on this side of the city until the early 12th century- to enclose this area within the defended circuit. This did not apparently result in any great immediate outburst of urbanisation, however, and most of the great area between the

The other major change to the area was the creation of the City Wall upon which we now stand- which, to the surprise of many, did not actually exist on this side of the city until the early 12th century- to enclose this area within the defended circuit. This did not apparently result in any great immediate outburst of urbanisation, however, and most of the great area between the  The last traces of the boggy former tributary valley were filled in around 1827 by the construction of the great embankment to carry the approach road to the

The last traces of the boggy former tributary valley were filled in around 1827 by the construction of the great embankment to carry the approach road to the  Passing the boarded-off site of the recently-demolished Police HQ, we

find ourselves

standing

in Nun's

Road,

so

called

because

it

occupies

part

of

the

lands

of

the

Benedictine

Passing the boarded-off site of the recently-demolished Police HQ, we

find ourselves

standing

in Nun's

Road,

so

called

because

it

occupies

part

of

the

lands

of

the

Benedictine  When that house was removed, the arch was transferred to

When that house was removed, the arch was transferred to

Passing along Nun's Road, we soon come to a narrow lane on the right bearing the evocative name of Blackfriars. This marks the approximate boundary between the precincts of the nuns of St. Mary's and the Dominican Friary, whose lands extended from here almost as far as

Passing along Nun's Road, we soon come to a narrow lane on the right bearing the evocative name of Blackfriars. This marks the approximate boundary between the precincts of the nuns of St. Mary's and the Dominican Friary, whose lands extended from here almost as far as  All was to no avail however, and the Dominicans, together with the other two Chester friaries, surrendered their house to Henry VIII's commissioners on 15th August 1538. An inventory of the buildings and contents were made which, aside from the stained glass in the windows and the lead on the roofs, found "little of value"- the monks having presumably disposed of all vestments, plate and other valuables bore the inevitable befell them.

All was to no avail however, and the Dominicans, together with the other two Chester friaries, surrendered their house to Henry VIII's commissioners on 15th August 1538. An inventory of the buildings and contents were made which, aside from the stained glass in the windows and the lead on the roofs, found "little of value"- the monks having presumably disposed of all vestments, plate and other valuables bore the inevitable befell them.  Some fragments survived for much longer- in his 1856 work, The Stranger's Guide to Chester, Thomas Hughes, after a description of the Roodee, wrote, "we will now return to the Walls, noticing as we pass through the

Some fragments survived for much longer- in his 1856 work, The Stranger's Guide to Chester, Thomas Hughes, after a description of the Roodee, wrote, "we will now return to the Walls, noticing as we pass through the  If

you

walk

down

the

steps

to

the

racecourse

and

grub

about

behind

a

lot

of

brambles,

debris

and

portable

buildings,

you

will

be

rewarded

with

the

sight

of

the

massive

stones

of

what was once the Roman

harbour

wall,

(right)

where

once

war

gallies

tied

up

and

the

trading

ships

of

the

empire

discharged

their

cargoes

of

wine

and

spices.

Although

only

a

few

courses

of

these

stones

show

above

ground,

they

extend

for at

least another

15

feet

underground

for

much

of

the

length

of

the

wall

between

here

and

the

If

you

walk

down

the

steps

to

the

racecourse

and

grub

about

behind

a

lot

of

brambles,

debris

and

portable

buildings,

you

will

be

rewarded

with

the

sight

of

the

massive

stones

of

what was once the Roman

harbour

wall,

(right)

where

once

war

gallies

tied

up

and

the

trading

ships

of

the

empire

discharged

their

cargoes

of

wine

and

spices.

Although

only

a

few

courses

of

these

stones

show

above

ground,

they

extend

for at

least another

15

feet

underground

for

much

of

the

length

of

the

wall

between

here

and

the  As is frequently the case in monuments of this class, the upper portion is obtusely pointed, and has a species of tympanum or recessed compartment, with a carving in relief, representing Callimorphus on a couch in a recumbent posture, with his son Serapion resting on his lap. Near the side of this couch or bed is a small, gracefully formed stand; and, to the left of this, an unmistakeable amphora. Height of the slab, 4 feet 2 inches; width, 2 feet 3 inches; and average thickness about 6 inches.

As is frequently the case in monuments of this class, the upper portion is obtusely pointed, and has a species of tympanum or recessed compartment, with a carving in relief, representing Callimorphus on a couch in a recumbent posture, with his son Serapion resting on his lap. Near the side of this couch or bed is a small, gracefully formed stand; and, to the left of this, an unmistakeable amphora. Height of the slab, 4 feet 2 inches; width, 2 feet 3 inches; and average thickness about 6 inches. Here we

see

a

view

of

the

Roodee-

a

small

detail

from

this

Here we

see

a

view

of

the

Roodee-

a

small

detail

from

this  In centuries gone by, each parish was responsible for the welfare of its poor and destitute. By the start of the 18th century, a system of Poor Houses was introduced, one for each parish. The records of St Mary’s Parish show that the appointed Master of its Poor House was expected to abide by many rules, just a few examples being:

In centuries gone by, each parish was responsible for the welfare of its poor and destitute. By the start of the 18th century, a system of Poor Houses was introduced, one for each parish. The records of St Mary’s Parish show that the appointed Master of its Poor House was expected to abide by many rules, just a few examples being: