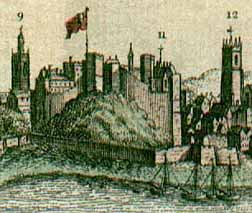

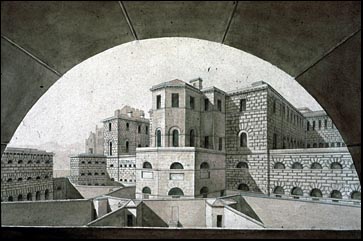

|

n

the

right,

we

see

Chester

Castle-

in

a

small

detail

from

this view

of

Chester-

which

appeared

in

the London

Magazine in

1753.

A

quarter

of

a

century

later

this

mighty

structure

would

be

almost entirely gone,

swept

away

to

make

room

for

the

buildings

that

occupy

the

site

to

this

day. n

the

right,

we

see

Chester

Castle-

in

a

small

detail

from

this view

of

Chester-

which

appeared

in

the London

Magazine in

1753.

A

quarter

of

a

century

later

this

mighty

structure

would

be

almost entirely gone,

swept

away

to

make

room

for

the

buildings

that

occupy

the

site

to

this

day.

The

rebuilding

of

Chester

Castle

took

37

years,

delays

being

caused

by

financial

problems,

the

need

for

two

separate

Acts

of

Parliament,

and

the

fact

that

much

of

the

building

work

was

undertaken

by

a

badly-housed

and

often

undernourished

population

of

convicts.

Architect Thomas Harrison himself

was

also

occasionally

found

to

be

at

fault-

he

was

threatened

with

dismissal

for

failing

to

produce

plans

and

drawings

on

time,

and

did

not

actually

move

from

his

home

in

Lancaster

to

supervise

the

project

until

1794,

three

years

after

work

had

started.

He

spent

the

rest

of

his

life

in

Chester,

living first in Folliot House in Northgate Street and then building

himself

a

fine house,

in

close

proximity

to

his

new

castle. This was St. Martin's Lodge, a simple and elegant, understated piece of Regency architecture, which remains with us today and, until recently, was utilised for administrative purposes by Cheshire Police. With their relocation in 2003 to a new HQ in Winsford and the demolition of their Chester HQ, the building became redundant and, at the time of writing, is for sale- boarded up and looking rather forlorn. Of recent times, we have heard of two potential buyers, one of whom wishes to establish a school there and the other a pub! We shall just have to wait and see..

Harrison

became

County

Surveyor,

his

only

public

appointment,

in

1815

at

the

age

of

71,

and

he

eventually

died

in

1829

at

the

ripe

old

age

of

85,

with

a

national

reputation

for

a

range

of

fine

public

buildings,

bridges

and

country

houses. Harrison

became

County

Surveyor,

his

only

public

appointment,

in

1815

at

the

age

of

71,

and

he

eventually

died

in

1829

at

the

ripe

old

age

of

85,

with

a

national

reputation

for

a

range

of

fine

public

buildings,

bridges

and

country

houses.

Architectural critic Nikolas

Pevsner wrote

of

Harrison's

remodelled Castle: "what

he

has

achieved

here

is

one

of

the

most

powerful

monuments

of

the

Greek

Revival

in

the

whole

of

England".

When

Grosvenor

Street

had

been

created

in

1825

to

link

the

city

with

Harrison's

new Grosvenor

Bridge,

it

had

been

necessary

to

demolish

an

ancient

church

dedicated

to St. Bridget and

he

designed

a

new

church

bearing

the

same

dedication,

which

was

erected

close

to

the

recently-rebuilt

castle.

The first stone was laid by the Bishop of Chester on October 12th 1827. Harrison

himself was

laid

to

rest

in

the

churchyard

here less than two years later, in March 1829.

When

this

church

(you

can

see

a

picture

of

it

on

the previous

page)

was

in

turn

demolished

during

the

1960s

to

make

way

for

a

traffic

island

on

the

new

Inner

Ring

Road,

his

remains

were

transferred

to

Blacon

Cemetery

on

the

edge

of

the

city.

The

exact

location

of

Harrison's

former

vault

is

not

certain

but

is

thought

to

lie

somewhere

under

the

pavement

in

Grosvenor

Street-

and

marked

by

a

manhole

cover- not

much

of

a

memorial

to

such a

great

man!

Old Soldiers

Some

sorry traces

of

the

second

St. Bridget's

churchyard

do remain

with

us

today,

however.

Should

you

ever

pass

this

way,

you

will

observe

that

a

number

of

gravestones

remain,

shockingly neglected,

still under their yews on

a

dusty

patch

of

land

next

to

the

new

magistrate's

court

building.

More surprisingly, some may be seen on

the

traffic

island

itself! Numerous burials remain beneath the grass but just two stones are now visible- and only one of these is an actual gravestone. A tall obelisk is a memorial to the great nonconformist biblical commentator Matthew Henry (1662-1714) which was paid for by public subscription and erected in St. Bridget's Churchyard in 1860. Henry himself lies in an unmarked grave within Holy Trinity Church- the Guildhall- in Watergate Street.

The other, a humbler affair, unnoticed by virtually all who pass by, is the grave of a truly remarkable old soldier. Its lengthy inscription reads (excuse any mistakes- it is quite faded now):

"In memory of Thomas Gould, late of the 52nd Regiment L. I. (Light Infantry). Died 1st November 1865 aged 72 years, 46 of which were spent in the service of his country. He was present at the following engagements: Vimeara, Corunna, crossing the Coa near Almeida, Eusago, Pumbal, Redinha, Condeixe, Foz d'Avoca, Sabugal, Fuentis D'ongle, storming of Ciudral, Rodrigo and Fadajos, Salamanca, San Munos (taken prisoner), St. Millan, Pyrenees, storming of the French entrenchments at Vera (wounded), Nivelle, passage of the Neve, Orthez, Tarrez, Toulouse and WATERLOO. He received the Peninsula Medal with 13 clasps and the Waterloo Medal. This stone is placed over him by a few friends." "In memory of Thomas Gould, late of the 52nd Regiment L. I. (Light Infantry). Died 1st November 1865 aged 72 years, 46 of which were spent in the service of his country. He was present at the following engagements: Vimeara, Corunna, crossing the Coa near Almeida, Eusago, Pumbal, Redinha, Condeixe, Foz d'Avoca, Sabugal, Fuentis D'ongle, storming of Ciudral, Rodrigo and Fadajos, Salamanca, San Munos (taken prisoner), St. Millan, Pyrenees, storming of the French entrenchments at Vera (wounded), Nivelle, passage of the Neve, Orthez, Tarrez, Toulouse and WATERLOO. He received the Peninsula Medal with 13 clasps and the Waterloo Medal. This stone is placed over him by a few friends."

It is easy to imagine the old warrior, having, against all odds, surviving all those terrible battles of the Napoleonic Wars, returning to Chester and growing old, enjoying his retirement and sitting in a favoured corner of his local pub (doubtlessly, as befits a military man, somewhere here in the vicinity of the Castle) regailing his friends with all manner of blood-curdling tales from his long career. They, and doubtlessly also the young and as-yet unblooded members of the garrison, would have been glad to buy him a pint or two and, when the time came, give him a good send-off and a decent burial. We wonder what he would make of his present situation!

Our photograph shows Thomas' grave on the busy traffic island with Matthew Henry's memorial and the Castle behind. A larger version of it may be seen here.

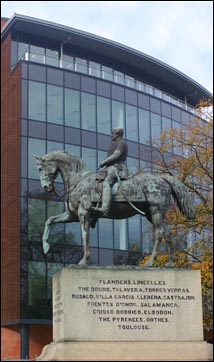

Standing before gateway to Chester Castle is a bronze equestrian statue of Stapleton Cotton, Viscount Combermere, which was erected in 1865. The second son of Robert Cotton of Combermere Abbey in Cheshire, Stapleton began his military career at 16 years of age, serving as a Second Lieutenant with the Welsh Fusiliers. He later purchased a Captaincy with the 6th Dragoon Guards and served in Flanders during the campaigns of the Duke of York. Still in his early twenties he was a comrade ofKing George III and served with the Light Dragoons at Cape Colony in 1796. Three years later he was involved with the storming of Seringapatam and following the death of his brother became heir to the Baronetcy and returned home to England.

Cotton soon after undertook further military service, helping to suppress a rebellion in Ireland and by 1805 had achieved the rank of Major General. In 1808 he was campaigning in Portugal and was promoted once again, to the rank of Commander serving under Wellington. He was cited for his actions during the Battle of Salamanca in 1812 and was wounded shortly after the conflict. Thomas Gould probably served under him there. Within two years he was raised to the peerage and by 1817 had been appointed as Governor of Barbados. Between 1822 and 1825 he was commanding British troops in Ireland, but actually ended his military career in India. His capture of the seemingly impregnable fortress at Bhurtporea was so remarkable that he was created a Viscount and by 1834 had been appointed as a Privy Councillor. In 1855 he was promoted to the rank of Field Marshal and 10 years later, 21st February 1865, died peacefully at his home at Clifton, aged 92 years. Cotton soon after undertook further military service, helping to suppress a rebellion in Ireland and by 1805 had achieved the rank of Major General. In 1808 he was campaigning in Portugal and was promoted once again, to the rank of Commander serving under Wellington. He was cited for his actions during the Battle of Salamanca in 1812 and was wounded shortly after the conflict. Thomas Gould probably served under him there. Within two years he was raised to the peerage and by 1817 had been appointed as Governor of Barbados. Between 1822 and 1825 he was commanding British troops in Ireland, but actually ended his military career in India. His capture of the seemingly impregnable fortress at Bhurtporea was so remarkable that he was created a Viscount and by 1834 had been appointed as a Privy Councillor. In 1855 he was promoted to the rank of Field Marshal and 10 years later, 21st February 1865, died peacefully at his home at Clifton, aged 92 years.

Returning once more to the first St. Bridget's Church, in early May 2002, while investigating a reported leak at the junction of Grosvenor and Bridge Streets, gas engineers started unearthing large quantities of human bones! An engineer at the scene conjectured, "The gas main must have been laid through the old crypt of St. Bridget's and it was completely surrounded by bones. We must have dug out at least a hundred skulls".

As the discovery became noticed by passers-by, an amazed crowd "three deep" started to assemble, at which point the gas company called in the council archaeology service to investigate. City archaeologist Keith Matthews, said that the bones were between 200 and 600 years old and he was starting a full investigation to find out how they could have been left behind when the church was demolished and its incumbents supposedly moved in 1832.

The remains had been buried under the chancel of the old church. They were described as being "in remarkably good condition"- but it turned out that the quantity of bones found had been, unsurprisingly, grossly exaggerated by the local press.

Today,

the

Castle

houses Chester

Crown

Court,

some

of

the

departments

of Cheshire West and Chester Council (formerly Cheshire

County

Council)

and

the

fascinating Cheshire

Regiment

Military

Museum.

With

the

exception

of

occasional

patches

of

medieval

walling,

the

only

survivor

of

the

great

castle

in

which

Henry

Bolingbroke

imprisoned

Richard

II

in

1399

is

the

three-storey

red

sandstone

tower

of

c.1200

curiously

named Agricola's

Tower-

it

certainly

has

no

Roman

connection-

and

even

this

was

refaced

by

Harrison.

This

was

one

of

the

towers

of

the

Inner

Bailey.

The

site

of

the

Outer

Bailey

is

represented

by

Harrison's

courtyard,

the Shire

Hall occupies

the

site

of

the

medieval

Great

Hall,

and

the

barracks

wing

that

of

the

outer

gatehouse.

(Curiously,

there

is

a

record

that,

in

1581,

the

city

magistrates

bought

the

old

Shire

Hall

in

the

Castle "for

six

Cheshire

cheeses",

and

moved

it

to

the Market

Square where

it

was

first

served

as

a

granary,

and

was

then

appropriated

by

the

city's

butchers,

and

became

the flesh

shambles). (Curiously,

there

is

a

record

that,

in

1581,

the

city

magistrates

bought

the

old

Shire

Hall

in

the

Castle "for

six

Cheshire

cheeses",

and

moved

it

to

the Market

Square where

it

was

first

served

as

a

granary,

and

was

then

appropriated

by

the

city's

butchers,

and

became

the flesh

shambles).

The

Inner

Bailey

was

to

the

south,

beyond

Harrison's

armoury

wing,

and

the

so-called Agricola's

Tower was

sited

between

the

inner

gatehouse

and

the

Inner

and

Outer

Bailey

walls.

Its

top

floor

houses

the

fine

Norman

/

Early

English Chapel

of St. Mary

de

Castro,

where

have

recently

been

discovered

some

very

fine

ceiling

paintings,

hidden

under-

and

preserved

by-

chemical

deposits

from

the

gunpowder

which

was

once

stored

here.

In

the

middle

of

April

2001,

we

learned

that

two

of

the

buildings

within

the

castlecomplex,

Colvin

and

Napier

Houses,

had

been

lying

unused

for

the

past

three

years

and

had

been

put

into

the

hands

of

an

estate

agent

with

a

view

to "redeveloping

them

for

commercial

use". Critics

at

the

time

pointed

out

the

absurd

situation

of

the

Lord

Chancellor-

in

the

face

of

great

public

criticism-

choosing

to

establish

his

new

County

Courthouse

in

the

grossly-inappropriate

setting

of

the

McLean

office

block

newly

erected

on

top

of

a

portion

of

Chester's

Roman amphitheatre when

all

the

time

these

dignified

buildings,

located

right

next

door

to

the

Crown

Court

and

just

over

the

road

from

the

Magistrate's

Court,

were

sitting

empty (and remain empty thirteen years later, in 2014!)

Promoters of Chester's 'heritage industry' have long been aware that our Castle, despite its remarkable historic connections, attracts relatively few visitors. Few indeed would deny that its buildings lack the magnificence of ancient castles such as that at Conwy, fifty miles or so along the North Wales coast. Perhaps the unattractive large car parking area puts them off, or the presence of the courts and council offices leads visitors to believe that they would not be welcome here.

But then, in November 2002, the local press reported that plans were afoot to "raise the profile" of Chester Castle. Planners and councillors will apparently "seek to balance the need to conserve the historic site with the need for a 'here and now' solution that would attract visitors into the area". Further reading revealed that the essence of the plan involved the inviting of commercial developers to  submit proposals for restaurants, bars, offices, even a hotel was envisioned. Just the types of businesses appearing in over-large numbers throughout the rest of the city, and consequently hardly an original or particularly exciting idea. Depending upon the quality of the businesses invited to participate in the scheme- and the levels ofrents demanded for the new commercial premises- the end result could be a vibrant and welcoming addition to our city's historic attractions- or it may be vulgar beyond belief. Only time will tell. submit proposals for restaurants, bars, offices, even a hotel was envisioned. Just the types of businesses appearing in over-large numbers throughout the rest of the city, and consequently hardly an original or particularly exciting idea. Depending upon the quality of the businesses invited to participate in the scheme- and the levels ofrents demanded for the new commercial premises- the end result could be a vibrant and welcoming addition to our city's historic attractions- or it may be vulgar beyond belief. Only time will tell.

As for making the Castle more accessible- while visiting the Castle in October 2009 this writer was surprised to find access to Agricola's Tower and much else blocked off by a large locked gate! A sign on it informed him that these areas, formerly open to anyone who was interested, would only be accessible during 'official' visits conducted exclusively by the Chester Guild of Registered Tourist Guides. We are informed that the closure has been reluctantly imposed due to drug taking and other antisocial behaviour taking place in the Castle precinct.

The good news is that the excellent nearby Grosvenor Museum is the keyholder for the Castle and will be pleased to conduct supervised visits by appointment- 01244 402033. And English Heritage are determined that an answer will eventually be found to the problems of increasing public accessibility versus those of protecting the building and staff security.

In November 2009, 'Piloti', the eminent architecture correspondent of Private Eye magazine wrote the following damning criticism of the manner in which both the Castle and the Grosvenor Bridge have been treated of recent years:

"Chester Castle is listed at Grade I. As designed by Thomas Harrison in 1785, the Castle was rebuilt as a grand composition of county buildings. Pevsner described the result as “one of the most powerful monuments of the Greek Revival in England”. But today you will find it a supreme example of municipal neglect and philistinism.

Electric cables and pipes disfigure the once magnificent ashlar stonework, which is also being damaged by plants growing from joints and parapets. A tree rises from the roof of the entrance gate or propylaeum. This was pointed out to Chester city council four years ago. Nothing has happened since– except that the tree has grown bigger. English Heritage looks after the surviving medieval parts of the castle: why doesn’t it do something?

Nearby is the Grosvenor Bridge across the river Dee, also designed by Harrison and listed at grade I. When it opened in 1833, it was the largest single arch stone bridge in the world with a span of 200 feet. This amazing, beautiful structure is also neglected and vandalised. Chester is as wealthy as it is pleased with itself; is there any reason why its council should not try to look after buildings in the city of national importance?"

Five years after the Eye report- October 2014- nothing at all would appear to have changed, except that more chunks of masonry have reportedly fallen from Harrison's grand Propylaeum.

The Prison

From

earliest

times,

prisoners

of

every

rank

from

King

to

peasant

were

confined

at

Chester

Castle. People

were

imprisoned-

and

frequently

executed-

for

trifling

offences,

and

inprisonment

in

those

ancient

dungeons

must

always

have

been

a

terrible

experience;

crowded

together

in

filthy

conditions

and

suffering

an

existence

of

almost-total

inactivity,

often

in

shackles

fastened

to

the

wall. From

earliest

times,

prisoners

of

every

rank

from

King

to

peasant

were

confined

at

Chester

Castle. People

were

imprisoned-

and

frequently

executed-

for

trifling

offences,

and

inprisonment

in

those

ancient

dungeons

must

always

have

been

a

terrible

experience;

crowded

together

in

filthy

conditions

and

suffering

an

existence

of

almost-total

inactivity,

often

in

shackles

fastened

to

the

wall.

The Chester Plea Roll in 1435 recorded the terrible punishment of 'pressing', meted out to one who refused to defend himself: "Thomas Broune of Irby complained to the Justice of Chester that John Strete of Nantwich stole a horse of his, worth 12s. Strete was arrested, but refused to plead; he could speak but of his malice he would not. The jury convicted him and the sentence was pronounced: let him be sent back to prison in the King's Castle of Chester and there be kept under strict custody, lying naked upon the floor; let iron above what he can carry be placed upon his body; as long as he lives let him have a morsel of bread one day and the next a drink of water from the nearest prison gate, until he shall die there in the said prison."

By

the

middle

of

the

'civilised'

18th

century-

and

the

massive

increase

in

prisoners

of

war "brought

in

by

the

cartload" following

the Jacobite

Rebellion of

1745,

overcrowding,

bad

food

and

filthy

conditions

led

to

outbreaks

of

disease-

notably

typhus-

resulting

in

large

numbers

of

deaths

among

the

inmates.

In

addition,

the

advent

of

the American

War

of

Independence made

it

more

difficult

to

transport

prisoners

to

the

plantations,

as had been the norm previously, leading

to

a

further

increase

in

the

population.

In

the

following

year,

a

letter

recorded "There

is

a

very

contagious

and

mortall

Distemper

in

the

Castle

of

which

the

Gaoler

and

his

wife

are

dead

and

Rebells

and

Debtors

in

abundance.

Since

the

Gaoler's

death

the

Rebells

have

attempted

to

knock

the

Turnkey's

brains

out

and

have

cutt

and

mangled

him

desperately".

In

1783,

the

great prison

reformer John

Howard visited

Chester.

(His

name

lives

on

in

today's Howard

League

for

Penal

Reform). On

a

visit

overseas,

he

had

been

captured

by

privateers

and

imprisoned

in

terrible

conditions

in

France.

After

his

release,

this

bitter

experience

led

him

to

devote

his

considerable

energies

and

fortune

to

campaigning

for

an

improvement

in

prison

conditions. He

persuaded

the

government

to

order

gaolers

to

be

paid

properly-

formerly

they

were

forced

to

live

on

what

they

could

extort

for

the

inmates-

and

prisons

to

be

kept

clean

and

their

occupants

decently

fed. He

described

the

medieval Northgate

Gaol as "insufficient,

inconvenient

and

in

want

of

repair" and

compared

it

to

the Black

Hole

of

Calcutta.

Stung

by

Howard's

criticisms,

the

city

authorities

realised

something

had

to

be

done,

so,

as

part

of

the

rebuilding

of

the

Castle,

a

new

prison

was

commissioned

and

opened

in

1792. Stung

by

Howard's

criticisms,

the

city

authorities

realised

something

had

to

be

done,

so,

as

part

of

the

rebuilding

of

the

Castle,

a

new

prison

was

commissioned

and

opened

in

1792.

Harrison

paid

attention

to

the

recommendations

of

the

reformers,

and

consuted

the

leading

prison

architect

of

the

day, William

Blackburn.

His

design

aimed

to

provide

the

inmates

with

dry

and

airy

cells,

and

the

sexes

were

separated

for

the

first

time.

Different

classes

of

prisoner

were

also

segregated-

debtors

were

housed

in

'airy

yards'

on

the

upper

level,

said

to "command

a

delightful

view

of

the

fine

ruins

of

Beeston

Castle".

Upon

completion,

Harrison's

gaol

was

praised

as "in

every

respect

one

of

the

best-constructed

goals

in

the

Kingdom". However,

in

1817

the

architect James

Elmes commented "No-one

viewing

this

edifice

can

possibly

mistake

it

for

anything

but

a

gaol,

the

openings

as

small

as

convenient

and

the

whole

external

appearance

made

as

gloomy

and

melancholy

as

possible".

On 14th August 1878, the London Times reported and exciting event at the Castle: "A fire broke out at Chester Castle on Monday evening, beneath the new court, which has recently been erected at a cost of £10,000. As soon as the flames were observed the men stationed at the Castle turned out and manned their engine. A window in the carpenter's store-room, in which the fire was raging, was broken, and volumes of water were poured in. The scene was exciting, for on one side the county prisoners were incarcerated, and on the other, in immediate proximity to Caesar's Tower, separated only from the burning building by a guard's box, immense quantities of ammunition are stored. To prevent the fire from extending to this tower, therefore, was the chief object of the men, as an explosion would have inevitably been terribly destructive to life and property. In a short time the rmen mastered the flames though the fire continued to burn for some time afterwards. The Chester fire brigade was unable to be present in time to render assistance, in consequence of a failure of the telegraphic apparatus. The storage of so large a quantity of ammunition in the city will forthwith be the subject of discussion in the Town Council".

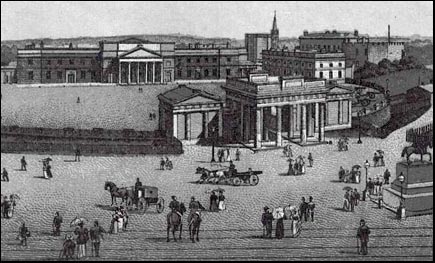

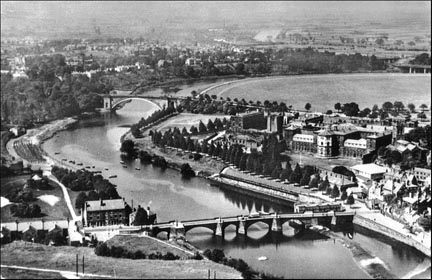

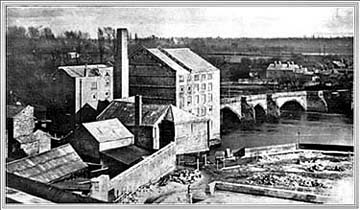

The

Castle

Gaol

is seen above in a view from 1835 and it and the Castle's

magnificent

setting

are made clear

in

the

fascinating

aerial

photograph

above that, dating from the early years of the twentieth century.

In

the

foreground

is

the Old

Dee

Bridge and

beyond

are

the Grosvenor

Bridge and

the Roodee.

You

can

also

see

another

photograph

of

the

gaol

as

viewed

from

the

river here. In addition, a fine watercolour of it by Louise Rayner is here and it may also be seen in this detail from John McGahey's remarkable 1855 View of Chester From a Balloon..

Improvements

In

the

area

between

the

Castle

walls

and

River Dee

formerly

ran

a

thoroughfare

known

as Skinner's

Lane where

many

of

the

less

glamorous

trades

of

the

town

were

practiced-

animal

skinners,

renderers

and

tanners,

among

others-

as

well

as

an

acid

factory.

By

modern

standards,

it

must

have

been

an

awful

place

and

a

major

source

of

pollution,

especially

at

a

time

when

the

Dee

supported

a

thriving

fishery

and

most

people's

domestic

water

supplies

came

straight

from

the

river! In

the

area

between

the

Castle

walls

and

River Dee

formerly

ran

a

thoroughfare

known

as Skinner's

Lane where

many

of

the

less

glamorous

trades

of

the

town

were

practiced-

animal

skinners,

renderers

and

tanners,

among

others-

as

well

as

an

acid

factory.

By

modern

standards,

it

must

have

been

an

awful

place

and

a

major

source

of

pollution,

especially

at

a

time

when

the

Dee

supported

a

thriving

fishery

and

most

people's

domestic

water

supplies

came

straight

from

the

river!

In

the

early

1830s,

the

city

authorities,

anxious

to

improve

the

situation,

acquired

this

area

and

extended

the

city

wall

to

enclose

it.

The long-defunct Chester

Courant in

July

1831

described

the

changes: "Most

of

the

buildings

have

been

taken

down,

as

well

as

a

great

portion

of

the

walls,

for

the

purpose

of

extension.

The

walls

will

be

diverted

from

their

original

course,

to

the

river

edge,

about

30

feet

from

the Bridgegate and,

having

continued

in

a

straight

line

along

the

river

for

285

feet,

will

make

an

angle

at

that

extent

and

join

the

old

walls

70

feet

from

the

present

west

boundary

wall

of

the

County

Gaol.

The

bulk

of

the

new

part

will

be

600

feet,

the

boundary

of

the

Gaol

will

follow

the

course

of

the

city

walls,

which

are

now

building

along

the

river,

at

low

watermark,

so

that

they

will

overhang

the

Dee

at

high

water..."

Thus,

the

wall

now

makes

a

right-angled

turn

to

the

south

east

and

drops

to

the

level

of

present-day Castle

Drive.

By

the

end

of

the

nineteenth

century,

the

prison

came

to

be

seen

as "inadequate

and

undesirable".

This

judgement

was

no

doubt

in

part

due

to

the

fact

that

it

occupied

a

prime

site

next

to

the

river,

considered

better

utilised

for

other

purposes.

Consequently,

in

the

early

years

of

this

century,

the

gaol

was

demolished,

along

with

the

fire-damaged Old

Dee

Mills nearby,

and

for

a

few

years

after,

the

site

was

utilised

as

a

drill

ground

for

the

local

artillery.

Today,

only

the

gaoler's

house

and

one

row

of

cells

survives.

The

photograph

above

shows

the

scene

just

before

the

prison,

the

old

mills

and

the

adjoining

industrial

premises

were

about

to

disappear

forever. By

the

end

of

the

nineteenth

century,

the

prison

came

to

be

seen

as "inadequate

and

undesirable".

This

judgement

was

no

doubt

in

part

due

to

the

fact

that

it

occupied

a

prime

site

next

to

the

river,

considered

better

utilised

for

other

purposes.

Consequently,

in

the

early

years

of

this

century,

the

gaol

was

demolished,

along

with

the

fire-damaged Old

Dee

Mills nearby,

and

for

a

few

years

after,

the

site

was

utilised

as

a

drill

ground

for

the

local

artillery.

Today,

only

the

gaoler's

house

and

one

row

of

cells

survives.

The

photograph

above

shows

the

scene

just

before

the

prison,

the

old

mills

and

the

adjoining

industrial

premises

were

about

to

disappear

forever.

Left: the Judge's coach leaves the Assizes at Chester Castle, guarded by the 'Javelin Men'. Another photograph of them may be seen on our Roodee pages...

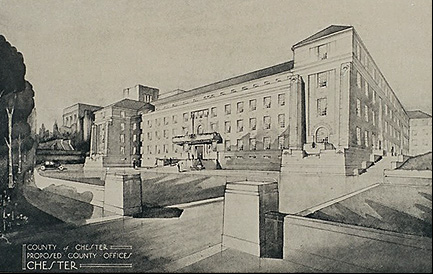

As

previously

mentioned,

the

central

block

of

the

Castle

had

been

used

as

the

administrative

HQ

of Cheshire

County

Council since

its

formation

in

1888.

Over

time,

the

increasing

complexity

of

the

council's

functions

made

the

need

for

more

office

space

necessary,

and

as

a

result

the

large

neo-Georgian County

Hall,

illustrated

right,

was

built

between

1938

and

1957

(work ceased between 1940-47,

delayed

by

the

war)

and designed

by

the

then

County

Architect,

E.

Mainwaring

Parkes,

occupying

the

site

of

the

old

prison

and

Skinner's

Lane.

It was officially opened by the Queen on July 11th 1957.

The materials with which the building was faced, Wattscliffe stone and Stamforstone grey facing bricks, were chosen in 1938, for a fee of 100 guineas, by the architect of the great Liverpool Anglican Cathedral, Sir Giles Gilbert Scott. The stone coat-of-arms above the main entrace was carved by the Liverpool sculptor H Tyson Smith.

The

architectural

historian

and

critic Nikolas

Pevsner dryly

commented

of

County

Hall

that

it

was: "not

an

ornament

to

the

riverside

view".

This attractive railway poster from 1938 shows an artist's impression of how the area looked immediately before it was built.

In the Summer of 2009, an almighty row broke out when it was proposed by the leadership of the newly-formed Cheshire West and Chester Council (a new creation recently risen from the ashes of the old Chester City and Cheshire County Councils) that County Hall should be sold to the rapidly-expanding Chester University for £10 mllion and that the council should take up offices within the newly-built HQ Building overlooking the Roodee. In the Summer of 2009, an almighty row broke out when it was proposed by the leadership of the newly-formed Cheshire West and Chester Council (a new creation recently risen from the ashes of the old Chester City and Cheshire County Councils) that County Hall should be sold to the rapidly-expanding Chester University for £10 mllion and that the council should take up offices within the newly-built HQ Building overlooking the Roodee.

Right: an architect's concept drawing of County Hall 1937

There was a considerable amount of opposition to the proposals on a number of grounds; value for money- County Hall was owned outright by the people of Cheshire whereas office space within HQ would have to be leased from the private developer, Liberty Properties at an as-yet unknown rent. Our council leader, however, claimed that the new building was energy-efficient and that, once scattered council services were brought together under one roof, there would be a considerable saving of money. It was claimed by some- but denied by others- that local people would be restricted in their access to their council in the new building.

Much discussion also took place among the residents of Handbridge, just across the Old Dee Bridge from County Hall, some of whom feared that their community would be turned into a 'student ghetto' like the Garden Lane area, with the large houses there being split into multi-occupancy student flats and a rise in parking problems, noise and unruly behaviour. Others, however, observed that most of us were students once, that they are by no means the disorderly rabble that some would have you believe and that an influx of bright young people would bring great benefits to the area (weighing the issues up, we were inclined to agree with them). And certainly, it seemed infinitely better that the building should be used for edcation rather than being flogged off to a hotel chain or being split up into yet more 'luxury' apartments, our city surely having reached saturation point in both of these.

Many pointed out the irony of the fact that the Conservatives, the current political administration, came to power largely because of widespread public opposition to a plan by the previous long-standing group- a dominant alliance of Labour and Lib Dem councillors- to build and move into a vast and ugly modern office complex on the Gorse Stacks car park, a structure that soon came to be derisively nicknamed 'The Glass Slug'. Yet here were the Tories now proposing to dump the premises they once so vocally defended and move into a spanking new glass palace of their own!

The 'Slug' was to have been built by the developers of the long-delayed Northgate Redevelopment Proposals in return for the use of the land behind the Town Hall where they would erect their vast complex of shops and apartments, together with a new theatre, library and market hall. Certain thwarted politicians blamed the people's unanimous rejection of the 'Slug' for the failure of the Northgate plan- leaving us today with an unsightly wasteland of rubble in the heart of our city- but most others ascribed its failure to the effect of the current economic climate upon large scale building projects such as this and consequent lack of demand for their shops and apartments. And many, including Chester's MP, Christine Russell, felt that it was "already out of date" and on many levels an unsuitable scheme for the heart of a beautiful and historic city anyway. The 'Slug' was to have been built by the developers of the long-delayed Northgate Redevelopment Proposals in return for the use of the land behind the Town Hall where they would erect their vast complex of shops and apartments, together with a new theatre, library and market hall. Certain thwarted politicians blamed the people's unanimous rejection of the 'Slug' for the failure of the Northgate plan- leaving us today with an unsightly wasteland of rubble in the heart of our city- but most others ascribed its failure to the effect of the current economic climate upon large scale building projects such as this and consequent lack of demand for their shops and apartments. And many, including Chester's MP, Christine Russell, felt that it was "already out of date" and on many levels an unsuitable scheme for the heart of a beautiful and historic city anyway.

It was observed that the very fact that the building of HQ continued to rise when all others failed seems to indicate that the council move was a 'done deal', agreed long before it ever came to the attention of the public. Some also said that it is the vanity of high-ranking members of the administration that has led to the move. As well as its swish hotel, conference centre, restaurants and bars, HQ was built to provide apartments and office accomodation of luxurious standards, providing spectacular views over the Roodee racecourse and beyond. It promised high levels of security from intruders to its tenants- and some expressed fears that those 'intruders' may include we, the residents who were actually paying for it. Add to all this the alleged funding shortfalls that were leading to mass council redundancies (at least 1,000 to date with more to come) and cuts to all manner of local services.

Whatever the pros and cons, in September 2009 the Planning Board of CWAC granted themselves planning permission for the sale and change of use of County Hall to take place and by Novemember the council had acquired all of the office space within the HQ development. An article on the Hill Dickinson website explains all. We were amused by the brief final sentence in this piece, "The council advised itself"...

The

Shipgate

As

we

pass

along

this

stretch

it

apppears

that

we

seem

to

have

somehow

mislaid

the

city

wall...

In

fact,

as

we

saw

earlier,

the

short

section

from

just

after

the Bridgegate and

passing

in

front

of

County

Hall

was

removed

at

the

time

of

the

construction

of

the

prison,

together

with

the

ancient Shipgate which

formerly

stood

in

this

place. As

we

pass

along

this

stretch

it

apppears

that

we

seem

to

have

somehow

mislaid

the

city

wall...

In

fact,

as

we

saw

earlier,

the

short

section

from

just

after

the Bridgegate and

passing

in

front

of

County

Hall

was

removed

at

the

time

of

the

construction

of

the

prison,

together

with

the

ancient Shipgate which

formerly

stood

in

this

place.

This narrow entrance, or postern,

was

known

as

the 'Hole

in

the

Wall' and

its

former

position

may

be

spotted

in

the

stonework

just

past

the

Bridgegate,

though

most

of

its

site

has

now

disappeared

below

the

level

of

the

roadway.

This

raising

of

ground

levels

is

a

normal

situation

in

ancient

towns-

generation

after

generation

of

buildings

rising,

being

demolished

and

new

ones

taking

their

place,

each

contributing

a

little

to

the

elevating

ground

level.

Thus,

the

remains

of

the

streets

and

buildings

inhabited

by

the

citizens

of

Roman

Deva

today

often

lie

many

feet

below

the

present

surface.

The

Shipgate

was

at

one

time

a busy

entrance

to

Chester

from

the

River

Dee

and,

before

the

silting

of

the

river

destroyed

the

port,

was

the

main

place

were

ships

would

discharge

their

cargo

and

send

it

into

the

city via packhorses up steep St. Mary's Hill.

An entry in the city assembly books from the 13th century tells us that, "ther was a waye for horse and man that went to a gate in the waules of the said cittie, the which way was cauled Shipgate; and Anendz this gate before the Bruge was mayde ther was a fferye bott that that brought bothe hors and man o'er Dee"

This

landing

place

for

the

ferry

from

Handbridge

stood

on

the

line

of

an

ancient

(pre?)

-Roman

ford

which

crossed

the

river

at

this

point. Another, long-forgotten, postern was once situated on the other side of the Bridgegate, known as the Horsegate or Capelgate, through which horses were led to be watered. The keeper of the Bridgegate was responsible for keeping these posterns securely locked at night and for collecting tolls from those who used them. Further to the west, the castle, too, had its own postern, "made for the benefit of them who lived in the castle to go down to the river".

The Horsegate was permanently blocked up in 1745, when there were fears of the city being attacked during the Jacobite Rebellion and the Shipgate was similarly closed up and reopened several times during periods of emergency over the centuries until it was

finally removed

in

1828

and,

after

spending

some

years

as

a

folly

in

a

private

garden

in Abbey

Square,

was

re-erected

in

1897

in Grosvenor

Park where it remains today,

as

you

may

see

in this

photograph.

And

now

we

will

go

in

search

of

Thomas

Harrison's

greatest

work-

one

he

did

not

live

to

see

completed-

the Grosvenor

Bridge...

Curiosities

from

Chester's

History

no. 20

- 1645 February: Parliament attacked the surburb of Handbridge, but were driven

off. The entire area razed to the ground by the citizens. In May, Brereton

withdrew his forces, the siege was raised and King Charles' forces relieved

the city. On September 19th, Colonel Jones marched from Beeston Castle and,

storming the outworks before dawn, gained Boughton and St.

John's Church, the tall tower of which was utilised most effectively

as an observation point and battery. (Byron had realised that the tower was

likely to be used for just this purpose, and early on ordered its demolition.

But, no doubt due to the people's affection for the venerable structure, his

order was never carried out, and the town was now paying the price. The tower

fell down of its own accord in 1881).

Parliamentary forces also besieged the

Mayor's house and seized his sword and mace, before being eventually repulsed.

The King arrived from Chirk Castle on 23rd September, entering via the Bridgegate and stayed at Sir Francis Gamul's house (still standing today: the Brewery Tap pub)- in Lower Bridge

Street. The decisive Battle of Rowton Heath (or Rowton Moor) took place on the 25th, when Sir

Marmaduke Langdale and Major Poyntz engaged the Parliamentary forces, but

were routed- 600 men were killed and 1,000 taken prisoner.

The King, after

watching the remnants of his army being harried through the suburbs from the Phoenix Tower (also known, because of this, as King Charles'

Tower) and later from the tower of the Cathedral-

where a stray shot killed an officer by his side- spent a final night in Chester

before fleeing to Denbigh Castle over the Old Dee Bridge accompanied by Sir

Francis Gamul, Captain Thropp, Mayor Cowper and 500 horsemen. These three

stayed with their King for three days before returning to Chester. Before

leaving, the King commanded the town to hold out for another 10 days, and

then surrender if they had not been relieved before then.

The loyalty of the

citizens was such that they held out for over four months, being reduced to

a diet of horseflesh, vermin and domestic pets. With the departure of the

King, the besiegers made a fierce attack on the city, overran the outer defences

and made a large breach in the City Wall near the Newgate (the repairs are still visible today)- before being driven off. During the

first 2 weeks of October, many further unsuccessful attacks were made upon

the Walls. They made a bridge of boats to cross the Dee, which the defenders

unsuccessfully tried to destroy- to this day, the city walls nearest to this

point bear the marks of cannon balls. The Dee

Mills and Watertower were several

times attacked by the besiegers and the citizens "kept in perpetual alarm"

by renewed assaults, and the explosions of cannon and grenados.

On 10th December, Brereton was joined by Colonel Booth and a body of Lancashire

troops, and Chester was attacked even more fiercely. The starving residents

refused nine summonses of surrender, until eventually the last shot was fired

on Christmas Day 1645, and a treaty was entered into- finally surrendering

on 3rd February 1646, "the terms being honourable to both sides".

It was later estimated that the siege had cost the city around £200,000, a

vast sum at the time, and the City Plate had been melted down to help fund

the defence. The number of lives that were lost during the conflict and the famine that

followed it will probably never be known.

Randle Holme III, who had been Mayor in 1643, wrote a moving description

of the massive destruction the Civil War had caused in Chester, which you

can read here.

We also recommend a stirring and well-researched novel by local author Norman

Tucker entitled Master of the Field, which evokes the atmosphere of the times like nothing else we've come across. Published in Chester in 1949

and unfortunately no longer in print, it is well worth trying to obtain.

|