elcome! We

commence

our exploration of Chester's ancient city walls by

standing

here, on

top

of

the Northgate. elcome! We

commence

our exploration of Chester's ancient city walls by

standing

here, on

top

of

the Northgate.

This

is

the

highest

point

in

the

city

and

from

here

you

can

observe

the

course

of

its ancient defensive ramparts

running

gently

downhill

on

each

side,

east

to

the Phoenix

Tower,

west

towards St. Martin's

Gate,

the Watertower and

the

Clwydian

hills

of

North

Wales

and,

less

obviously,

south

towards

the

city

centre,

the High

Cross and

beyond

to

the River

Dee.

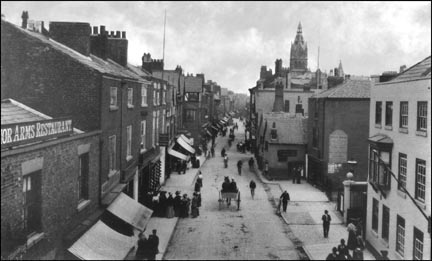

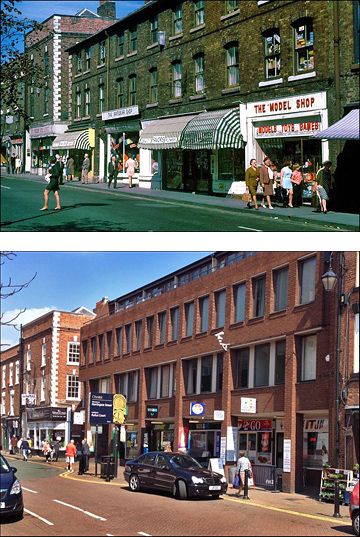

Right: Northgate Street 1967.

Courtesy of Phil Wilson

This Chester Virtual Stroll is but the latest in a long line

of guides to the splendours of our ancient city- many of which have been consulted and are named in the bibliography- but is the first to

be published exclusively on the World Wide Web, instantly and freely available

to you, wherever you may be (although your donations, sponsorship and advertising help keep us going and are always gratefully received!)

Bear in mind that our intention is not to provide a definitive history

of the City of Chester, many of which already exist (by far the richest online source is at British History Online) - but rather to provide a pleasant and illuminating

day out with a few anecdotes, pictures and personal comments thrown in at no extra cost.

Nevertheless, if you do need specific information about Chester,

Liverpool or their surrounding areas, don't hesitate to get in touch and

we will do our best to help or pass your enquiries on to those who can. All of your letters will be answered- and may even be published on our lively reader's comments pages!

Our first photographs show the view along Northgate Street as seen from the top of the Northgate; above on a sunny day in 1967, 'the summer of love' half a century ago, and below, as it appeared at the end of the nineteenth century. Not a lot of difference- and should the visitor compare them with the same view as seen today, it is truly remarkable how little seems to have changed, only the buildings in the right hand foreground of the Victorian image having since been replaced, as we shall learn later.

Close to where the ladies in the lower picture are queuing up for a bargain is the entrance to Abbey Green and Rufus Court, a fascinating community of bars, restaurants, cafes and specialist shops. Close to where the ladies in the lower picture are queuing up for a bargain is the entrance to Abbey Green and Rufus Court, a fascinating community of bars, restaurants, cafes and specialist shops.

You can read more about Rufus Court in our North Wall chapter and explore the fascinating businesses to be be found there both on ChesterTourist.com and on their own website..

It is interesting to compare these photographs with this painting of the same location and from around the same time as the earlier by the famous watercolourist Louise Rayner (some of her other fine images of Chester are here).

Two

thousand ago,

on

this

very spot

stood

the Roman gateway, the Porta

Decumana of

the

great

regional capital and military

fortress

of Deva. The Via

Decumanus was

the

name

given

to

the

main

north-south

street

of

a

Roman

town,

and

occasionally

to

other

large

streets

parallel

to

it.

It

entered

the

fortress

at

the

point

were

we

now

stand,

but

then

ran

slightly

to

the

right

(west)

of

the

modern

street

line,

at

an

angle

that

would

end

where

you

see

the

present

tower

of St. Peter's

Church,

at

the

Cross. In Roman times the open space we see today was filled with all manner of buildings but for many centuries it served as the home of Chester's markets and fairs, indeed being known, both then and now, as Market Square. However, since the opening of the great Town Hall on its west side in 1869, it has also been commonly referred to as Town Hall Square.

During your wanderings around our city, you may be intrigued to note how the main streets are named, in tribute to our founders, in both English and Latin. Chester is the only city in Britain where this occurs. During your wanderings around our city, you may be intrigued to note how the main streets are named, in tribute to our founders, in both English and Latin. Chester is the only city in Britain where this occurs.

The Dead Men's Room

The

Norman / medieval

gate

which, after a thousand years or so,

rose upon and incorporated the foundations of its

Roman predecessor,

was

in

the

care

of

the

sheriffs

of

the

city,

who

received

the

tolls

taken

on

goods

entering

here,

in

return

for

which

they

maintained

the

gate

and

the

terrible prison

housed

within

it,

attended

to

the

pillory

and

the

stocks,

executed

felons

and

robbers

sentenced

by

courts

throughout

the

whole

of

Cheshire (Chester being the County Town),

published

the

Earl's

proclamations

and

called

the

citizens

to

assembly "by

sound

of

the horn."

This

second

Northgate,

first

mentioned

in

documents

in

1096,

comprised

a "dark,

narrow

and

inconvenient

passage,

under

a

pointed

arch,

over

which

was

a

mean

and

ruinous

gaol." It was defended on the outside by a drawbridge. Almost five centuries later, in the city's accounts for 1569, we read, "For making the north-gate bridge new, grette joists and thick planks: £4 3s 2d". This

second

Northgate,

first

mentioned

in

documents

in

1096,

comprised

a "dark,

narrow

and

inconvenient

passage,

under

a

pointed

arch,

over

which

was

a

mean

and

ruinous

gaol." It was defended on the outside by a drawbridge. Almost five centuries later, in the city's accounts for 1569, we read, "For making the north-gate bridge new, grette joists and thick planks: £4 3s 2d".

The bridge we see in its place today was constructed in October 1772 as part of the construction of the Chester Canal. The following month, "Henry Bullock and Robert Mason, masons, were to compleate the bridge at the Northgate for the sum of eighty two pounds ten shillings".

People could be confined in the Northgate Goaol for all manner of offences, some quite trivial such as rowdyism, non payment of debts- and even the baking of poor quality bread (loaves had to marked with the 'baker's mark' so that they could, if necessary, be traced back to those responsible). The worst parts

of

the

prison- the main entrance to which was on the west side of the gate

were

excavated

from

the

bedrock

up

to

30

feet

below

the

street. Descriptions

written

in

the

17th

century

talk

of

them

being "noisome,

pestilential,

stinking,

and

crowded

with

venomous

creatures". One cell was known as 'the snake pit'-

and

another

a "dark

and

stinking

place

called

the Dead

Men's

Room" where

prisoners

who

had

been

condemned

to

death

were

confined,

"in

order

to make

them

more

callous

to

their

impending

fate". It had no windows, and was accessible only by a trapdoor in the roof.

Another

infamous cell

was known

as

the Chamber of Little

Ease, which was described by a contemporary visitor as "a hole hewed out in a rock; the breadth and cross from side to side was seventeen inches from the back to the great door; at the top seven inches, at the shoulders eight inches and at the breast nine inches and a half; with a device to lessen the height as they were minded to torture the person put in, by drawboards which shot over across the

two sides, to a yard in height or thereabouts".

Another account described it thus, "In the court of the said House of Correction in a hole in the side of a rock is a little prison place called the Little Ease in which stubborn youths are thrust, and a grate locked upon them, where they can neither stand, sit, kneel nor ly, but are bent in all their joyntes, & have no resting place for any part". Another account described it thus, "In the court of the said House of Correction in a hole in the side of a rock is a little prison place called the Little Ease in which stubborn youths are thrust, and a grate locked upon them, where they can neither stand, sit, kneel nor ly, but are bent in all their joyntes, & have no resting place for any part".

Right: Martin Moss has produced this evocative recreation of the old Northgate in its final, forbidding, form, as it would have appeared around the year 1750. The view is from outside the City Walls with Bishop Stratford's Bluecoat Charity School on the right. This was erected in 1717 and, unlike the dreadful Northgate Gaol, remains with us today.

The view also illustrates clearly what a great obstruction to traffic the old gate must have been, even in those days. It seems remarkable that its presence was tolerated into the early years of the nineteenth century.

A wonderful animated recreation of the old Northgate and its neighbourhood by Martin Moss may be viewed on his channel on YouTube.

You will also find there the talented Mr Moss's fly-bys of Beeston, Ewloe and Chester Castles among much else..

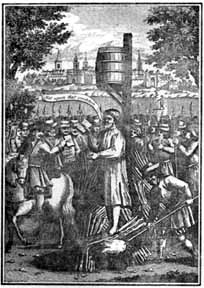

During the reign of Queen Mary, the clergyman and martyr George Marsh was held at the Northgate before being burned at the stake for heresy at nearby Boughton in April 1555. His brief stay there after his trial in the Lady Chapel of the Cathedral was recorded thus in chapter XVI of Foxe's Book of Martyrs (1563):

"After this the Bishop delivered him unto the Sheriffs of the city (then his late keeper bade him: Fare well, good George!- with weeping), which caused the officers to carry him to a prison at the Northgate where he was very straightly kept until the time he went to his death. During which time he had small comfort or relief of any worldly creature, for being in the dungeon none that willed him good could speak with him, or at least durst enterprise so to do for fear of accusation. And some of the citizens which loved him in God for the gospel's sake (whereof there were but a few), although they were never acquainted with him, would sometimes in the evening (at a hole upon the wall that went into the said prison) call to him and ask him how he did. He would answer them most cheerfully that he did well, and thanked God most highly that He would vouchsafe of His mercy to appoint him to be witness unto His truth and to suffer for the same. Once or twice he had money cast him in at the same hole, about ten pence at one time, and two shillings at another time, for which he gave God thanks and used the same to his necessity".

At the place of execution, he "was chained to the post, having a number of fagots under him, and a thing made like a firkin, with pitch and tar in it, over his head. The fire being unskilfully made, and the wind driving it in eddies, he suffered great extremity, which notwithstanding he bore with Christian fortitude. When he had been a long time tormented in the fire without moving, having his flesh so broiled and puffed up that they who stood before him could not see the chain wherewith he was fastened, and therefore supposed that he had been dead, suddenly he spread abroad his arms, saying, "Father of heaven have mercy upon me!" and so yielded his spirit into the hands of the Lord". At the place of execution, he "was chained to the post, having a number of fagots under him, and a thing made like a firkin, with pitch and tar in it, over his head. The fire being unskilfully made, and the wind driving it in eddies, he suffered great extremity, which notwithstanding he bore with Christian fortitude. When he had been a long time tormented in the fire without moving, having his flesh so broiled and puffed up that they who stood before him could not see the chain wherewith he was fastened, and therefore supposed that he had been dead, suddenly he spread abroad his arms, saying, "Father of heaven have mercy upon me!" and so yielded his spirit into the hands of the Lord".

The place where poor Marsh and countless others died so horribly, at the top of Barrel Well Hill in Boughton, just a mile or so from Chester Cross, is today marked by a commemorative obelisk which bears the inscription, "George Marsh born Dean, Co. Lancaster. To the memory of George Marsh martyr who was burned to death near this spot for the truth sake April 24th 1555. Also John Plessington 19th July 1679. Canonised Saint 25th October 1970."

A further memorial to him is in the lovely Church of St. John the Baptist which we will have the pleasure of visiting later in our journey.

From the reign of Elizabeth I in the 1560s, the Spanish Armada in 1588 to the so-called 'Popish Plot' concocted by Titus Oates in 1678, persecution of the Catholics resulted in many being imprisoned both here in the Northgate and at Chester Castle. One such was the above-named John Plessington, who suffered the ghastly punishment of being hanged, drawn and quartered at Boughton in 1679 for the crime of being a Catholic priest.

In

the

17th

century,

during

Oliver

Cromwell's

English

Commonweath,

Chester's Quakers were

actively

persecuted

by

the

Puritans

and

Prebyterians,

and

many

of

them

were

imprisoned

at

the

Northgate.

Of

one

unfortunate, Richard Sale, it

is

recorded: "that,

being

a

portly

man,

he

was

too

large

vilWor

the

dungeon

known

as

Little

Ease,

but

was

nevertheless

squeezed

into

it

and

the

door

shut,

which

caused

the

blood

to

run

from

his

nostrils".

The Northgate was a foul place out of which few escaped and many died- but in which one or two conformed and went to church. One Ralph Langton, however, was confined here after he rashly boasted that "he would never go to church for any man's pleasure in Chester".

The

cells

were

continually

wet

and

the

only

way

air

could

enter

was

by

the

way

of

pipes

which

led

from

the

street

above.

There

is

a

story

that

when

some

men

were

suspected

of

sheep

stealing

and

one

of

them

was

captured

and

placed

in

the

Dead

Man's

Room,

his

accomplices

stuffed

rags

into

these

pipes,

suffocating

the

prisoner

overnight

before

he

had

a

chance

to

reveal

their

names.

In 1494, it was recorded that, "Mistress Marion Houghton, wife of a servant of the Abbot of St. Werburgh, in Northgate Street did assault Elizabeth - and struck her on the head with her right fist, dragged her hair, and struck her face so that blood flowed freely. Sir John Savage, Mayor, ordered two Sheriffs to arrest both women and deliver them to Oliver Hepay, Keeper of the Northgate Gaol, there to remain until they could find sufficient security to keep the peace". In 1494, it was recorded that, "Mistress Marion Houghton, wife of a servant of the Abbot of St. Werburgh, in Northgate Street did assault Elizabeth - and struck her on the head with her right fist, dragged her hair, and struck her face so that blood flowed freely. Sir John Savage, Mayor, ordered two Sheriffs to arrest both women and deliver them to Oliver Hepay, Keeper of the Northgate Gaol, there to remain until they could find sufficient security to keep the peace".

In 1663, a widow named Elizabeth Powell was convicted of witchcraft. Debatably more fortunate than others, such as the three women who a few years earlier had been hanged at the Castle for the same offence, she was confined in the Northgate Gaol and remained there until she died six years later.

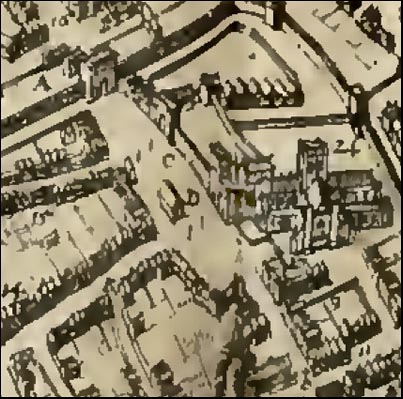

Right: Northgate Street and the Market Square as recorded in pen-and-ink in Daniel King's 'Vale Royal of England', 1656, a decade after the end of the Civil War. The old Northgate is at the top, giving access to a street that appears to be very much wider at its northern end than it is today.

In the 18th century, debtors, too, were confined at the Northgate, where they could be held for a decade or more, but their treatment was, relatively speaking. not as severe as for other classes of criminal. They were allowed to stroll about on the North Wall and even wander a little way down Northgate Street and 'gentlemen' could, for a weekly rent of five shillings, live in the relative comfort of the 'Blue Room'. Felons, too, had the use of a day room but they had to wear irons and return to their windowless cells at night.

Intriguingly, this debtor's prison seems also to have made itself available to paying guests! In the May 1879 edition of the Cheshire Sheaf, we read about "an old Cheshire character" by the name of Captain Robert Thomas, who had served in the American War and who "armed with a tremendous shillelagh after a Baccanalian debauch, would sally through the Rows and streets of the city, and fortunate was the sconce which avoided the indiscriminate sway of his arm; occasionally he played in the Rows upon his flute, which at times served him as a cudgel, and his music therefore must have been frequently out of tune"... He died in 1824, aged 77, "near the Northgate, where for over twenty years he had been a voluntary tenant of the debtor's side of the Chester City Gaol".

When

prison

reformer John

Howard visited

the

Northgate

Gaol

in

1787,

he

reported

that

both

convicted

prisoners

and

those

awaiting

trial

had

shackles

around

the

necks,

hands,

waists

and

feet

which

would

be

attached

to

the

floors

during

the

day

and

their

beds

at

night.

They

were

allowed

to

beg

for

several

hours

a

day-

a

necessity,

because

they

were

not

given

enough

food

to

live

on

by

the

authorities,

a

situation

Howard

described

as

a "disgrace

to

such

an

opulent

city." We

will

be

meeting

with

the

great

John

Howard

again

later

in

our

stroll,

when

we

visit Chester

Castle.

In addition to those at the scaffold and stake at Boughton, outside the city walls, untold numbers of public executions were carried out over the centuries at the Northgate Gaol. As late as 1801 it was recorded that two burglars, Aaron Gee and Thomas Gibson were hung here by being pushed out of windows in the attics on the gaol's south (city) side, a drop of just forty inches: "by means of the Drag, a machine of clumsy construction, both men were propelled from the aperture of a window without respect for decency. Forty feet above the roadway, their bodies beat against the windows and walls in a frighful manner, so as to break the glass in them".

On September 10th 1802, one Thomas Griffiths was sentenced to death here for stealing "one Gelding, the property of Samuel Jackson". In 1786, James Buckley was convicted of burglary and received the same harsh penalty. These sentences certainly appear severe when compared with the "six months imprisonment, and fine of 6s 8d with a recognizance of £100 to keep the peace for three years" imposed on John Davies on October 24, 1805. Mr Davies was found guilty of "wilfully, maliciously and with malice of aforethought drowning John English in the waters of the Ellesmere Canal". It would seem that, in Chester, property was deemed of greater value than life.

Immediately next to the Northgate on the east side of the street once stood a timber-built

tavern

known

as

the Hen

&

Chickens which

is

said

to "have

reaped

golden

harvests

when,

in

the

days

of

the

old

Northgate

Prison,

unfortunate

malefactors

suffered,

close

to

this

spot,

the

last

penalty

of

the

law

at

the

hands

of

the

public

hangman" (Hughes

1858). You can readily imagine the regulars, chairs out in the street and pots in hand, enjoying a grandstand view of their unfortunate fellow citizens being consigned to eternity.. Immediately next to the Northgate on the east side of the street once stood a timber-built

tavern

known

as

the Hen

&

Chickens which

is

said

to "have

reaped

golden

harvests

when,

in

the

days

of

the

old

Northgate

Prison,

unfortunate

malefactors

suffered,

close

to

this

spot,

the

last

penalty

of

the

law

at

the

hands

of

the

public

hangman" (Hughes

1858). You can readily imagine the regulars, chairs out in the street and pots in hand, enjoying a grandstand view of their unfortunate fellow citizens being consigned to eternity..

The old inn was entirely rebuilt in the early 19th century and in 1809 was called The Wheatsheaf- it appears as this in a list of polling stations in that year- but soon after becoming The Grosvenor Arms. The wheatsheaf is the Arms of the Grosvenor family. The 'hen & chickens' is a Christian emblem of Divine Providence and the name may have been chosen by the ecclesiastical authorities at the Abbey- today's Cathedral- upon whose land the inn stood. It seems somewhat irreverent to have bestowed the name on an ordinary inn so it is possible the premises once served as accomodation for pilgrims who sought the hospitality of the monks.

The licence was withdrawn in 1912 and the inn was divided to house three shops; it was later reunited to become a branch of Sayer's the Bakers until this closed in 2008. A restaurant now occupies the premises. Learn more about the many lost inns of Northgate Street here.

The dreadful Northgate Gaol

was

in

regular

use

for

over

700

years. By 1801 it was recognised as being desperately inadequate for its purpose and calls were made for its replacement. It was described by the Mayor, Daniel Smith, the Recorder, Hugh Leycester and other worthies as "insufficient, inconvenient and in want of repair. The place whereon the present gaol is situate is improper and inconvenient, the gaol ought to be removed to another part of the city". In 1807, this came about when a new City Gaol was erected across the city on a site near the walls overlooking the Roodee now occupied by the Queen's School. When

the old one

was

demolished

in

the

following

year,

abundant

proof

of

its

Roman

origin

was

found;

large

stones,

regularly

laid

without

mortar,

and

not

nearly

so

weathered

as

the

upper

courses,

laid

probably

five

or

six

hundred

years

later. Chester

guide

and

author Thomas

Hughes remarked

of

its

passing "the

gaol,

with

its

attendant

miseries,

has

gone,

but

the

dungeons

we

have

pictured

abide

there

still,

beneath

the

ground

we

are

now

standing

on-

though

filled

up,

it

is

true,

and

for

ever

absolved

from

their

ancient

uses".

And

such

remains

the

case

to

this

day.

Spare a moment to think of those awful dungeons still lying beneath your feet when you visit the place for yourself.

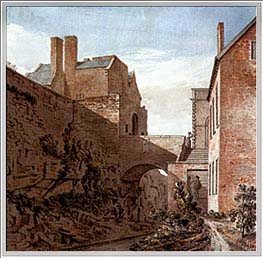

Here

is

a

beautiful

watercolour

of

the

final days of the medieval

Northgate

by Moses

Griffith (1747-1819).

The

stone

bridge

seen

crossing

the

canal

cutting

is

still

in

use

today

but

protective

iron

railings

have

since

been

added.

Notice

how

the

wall-top

walkway

went

round

three

sides

of

the

Northgate.

On

the

far

left,

you

can

see

the

diagonal

line

where

the

large

weathered

blocks

of

the

2nd

century

Roman

wall

ends

and

the

medieval

work

begins,

much

as

we

see

it

today. Here

is

a

beautiful

watercolour

of

the

final days of the medieval

Northgate

by Moses

Griffith (1747-1819).

The

stone

bridge

seen

crossing

the

canal

cutting

is

still

in

use

today

but

protective

iron

railings

have

since

been

added.

Notice

how

the

wall-top

walkway

went

round

three

sides

of

the

Northgate.

On

the

far

left,

you

can

see

the

diagonal

line

where

the

large

weathered

blocks

of

the

2nd

century

Roman

wall

ends

and

the

medieval

work

begins,

much

as

we

see

it

today.

This

writer,

for

one,

had

thought

that

the

Roman

wall

had

formerly

existed

beyond

this

point,

joining

with

the

medieval

gate,

and

that

it

had

been

cut

back

to

its

present

extent

when

the

gate

was

replaced

in

1808.

This

painting

shows

this

not

to

have

been

the

case.

It

may

have

been

an

oversight

by

the

artist,

but

he

was

60

years

old

when

the

old

gate

was

demolished, had a keen eye

and

presumably

knew

it

well.

The

other

side

of

the

canal,

where

a

utilitarian

electricity

substation

now

stands,

was

occupied

by

the House

of

Correction,

seen

on

the

right

of

the

picture- and more clearly, in the anonymous black and white drawing above- where 'petty'

crimes were

punished

by

confinement

and

hard

labour. In 1693, it was ordered that three apprentices, Joseph Harrison, John Litherland and George Eaton, were to be "committed to the House of Correction, and be there severally whipped for their disorderly behaviour within the hearing of this court and continue there until further notice".

The punishment seems to have had a beneficial effect as all three are recorded as being admitted as Freemen of the City in later years. One Richard Geary Smith was sentenced to one month's stay in the House of Correction on March 13, 1799, for being a 'rogue and vagabond'. On January 19th of the same year, Samuel Starkie received a month's sentence for deserting his wife and child, therefore leaving them chargeable on the Parish. Starkie also had to pay 2/6d to his wife or the Parish before he could be discharged.

The House of Correction also served as a sort of workhouse; in 1685, Ann Mynshull left in her will "rents for the maintainance of poor freemen's children at work in a house called the House of Correction standinge neare unto the Northgate".

Beyond

this at the top of the steps,

a

corner

of

the Bluecoat

School is

just

visible.

We

will

learn

much more

about

this

in our next chapter.

The

old Northgate

saw

much

action

during

the

Civil

War Siege

of

Chester in

1645-6.

Most

of

the

buildings

standing

beyond

it

outside

the

city

walls,

if

not

burned

by

the

besiegers

were

deliberately demolished

by

the

townspeople

themselves

so

as

not

to

afford

shelter

to

Parliamentary

snipers.

The

city's

principal

entrance,

the Eastgate had

been

blocked

with

earth

and

rubble

as

a

defensive

measure,

so

the

Royalist

defenders

used

this

gate

when

sallying

forth

to

attack

their

foes

surrounding

the

town.

More happily, a century later, a 1750 edition of the long-defunct news sheet, the Chester Courant, gave notice of a series of plays to be performed "for every night during the Fair-Week at the theatre near to the Northgate". We now have no clue where this theatre was located. More happily, a century later, a 1750 edition of the long-defunct news sheet, the Chester Courant, gave notice of a series of plays to be performed "for every night during the Fair-Week at the theatre near to the Northgate". We now have no clue where this theatre was located.

Also, in an August 1750 edition of the Courant, appeared the following announcement, "Notice of Benefit Performances. For the benefit of the prisoners in the Northgate and the Castle, on Thursday next will be presented "The Suspicious Husband" with a musical entertainment called "The Chaplet".

The

terrible medieval

Northgate

was

eventually replaced by

the

structure

upon

which

we

now

stand,

a miniature masterpiece of Neo-Classicism

designed

by Thomas

Harrison (1744-1829), a prolific architect whose works we will frequently encounter throughout our stroll around Chester, and

built

in

1808-10,

the

last

of

Chester's

ancient

fortified

gates

to

be

so

replaced.

On

the

north

side

is

the

inscription-

and

a

test

for

your

Latin:

PORTAM

SEPTEMTRIONALEM

SUBTRACTA

A

ROMANIS

VETUSTATE

JAM

DILAPSAM

IMPENIS

SUIS

AB

INTEGRO

PRESTITUENDAM

CURAVIT

ROBERTUS

COMES

GROSVENOR,

A.R.

GEORGII

TERTII

LI.

"The north gate built by the Romans being now about to disintegrate, Robert Earl Grosvenor has had it entirely restored at his own expense in the 51st year of the reign of George III."

And

on

the

south

appears

the

following:

INCHOATA

GULIELMO

NEWELL,

ARM,

MAI,

MDCCCVIII.

PERFECTA

THOMA

GROSVENOR,

ARM,

MAI.

MDCCCX.

THOMA

HARRISON,

ARCHITECTO.

'Gulielmo' (William) Newell served as Mayor of Chester in 1808-9.

Built of finely cut grey Runcorn sandstone, this

new

arch

was

commisioned

by Robert,

2nd

Earl

Grosvenor,

when

he

became

Mayor

of

Chester

in

1807-08.

Grosvenor initially wanted a 'Gothic' design so Harrison produced drawings of a "pretty confection" (illustrated right) with a parapet of arches carrying a vaulted passage over the road. He also, however, pointed out that the new gate would stand on the site of a Roman predecessor and was located close to an impressive surviving stretch of Roman wall and so persuaded Earl Grosvenor of the merits of an alternative design which, with its Doric columns, paid homage to Chester's Roman origins. Built of finely cut grey Runcorn sandstone, this

new

arch

was

commisioned

by Robert,

2nd

Earl

Grosvenor,

when

he

became

Mayor

of

Chester

in

1807-08.

Grosvenor initially wanted a 'Gothic' design so Harrison produced drawings of a "pretty confection" (illustrated right) with a parapet of arches carrying a vaulted passage over the road. He also, however, pointed out that the new gate would stand on the site of a Roman predecessor and was located close to an impressive surviving stretch of Roman wall and so persuaded Earl Grosvenor of the merits of an alternative design which, with its Doric columns, paid homage to Chester's Roman origins.

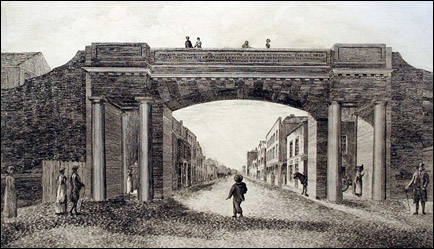

Left: Harrison's new Northgate in 1815

Harrison duly presented his proposals to the City Council's Assembly Committee,

but, when a vote was taken, only two were in support, the other ten preferring a copy of Joseph

Turner's Watergate,

built

twenty

years

earlier, in 1789

(Turner had also, in 1782, designed the replacement Bridgegate). Mr Anderson, the contractor who was supplying the stone for the project, said that he could build Turner's design for £280 rather than the £350 which Harrison estimated his would cost. Money considerations aside, there were also hints in the Minutes and in the ensuing public controversy that that some people considered Harrison a "pushy outsider" and party politics also enterered into the row, some supporting the recently-elected tory MP and others the city's other MP- Earl Grosvenor's own brother- who was a Whig.

Within a fortnight, Anderson had commenced the foundations for the Turner design but strong opposition was already being expressed in the city to the idea of a copy of an 'old-fashioned' gate when a more modern alternative was available. Grosvenor's faction, who were willing and able to pay the higher price, were eventually successful and the new gateway was built to Harrison's design. It was modified somewhat during the construction process; Harrison had wanted fluted columns on each side of the arch, rather than the plain Doric columns we see today, on the grounds that they were "more authentically Greek" but had been persuaded to drop the idea by the Town Clerk, who feared that the delicate flutings would be damaged by the mob "at a time of disputed elections". The modifications resulted in a more severe appearance that gained something of the "quiet simplicity and quiet grandeur" of his Shire Hall portico at the Castle, erected a few years earlier.

The

Northgate

hasn't

changed

much

since it was built 200 years ago.

The engraving above shows it in 1815, looking exactly as it does today. In stark contrast, the Market Square (or Town Hall Square, as it is generally known now) has altered a great deal. To illustrate the point,

below

is

an

interesting

old

etching

by George

Batenham showing

the

area

as

it

appeared

around

1817, a decade after the gate was rebuilt.

Virtually

all

the

buildings

shown

have

now

vanished. The

Northgate

hasn't

changed

much

since it was built 200 years ago.

The engraving above shows it in 1815, looking exactly as it does today. In stark contrast, the Market Square (or Town Hall Square, as it is generally known now) has altered a great deal. To illustrate the point,

below

is

an

interesting

old

etching

by George

Batenham showing

the

area

as

it

appeared

around

1817, a decade after the gate was rebuilt.

Virtually

all

the

buildings

shown

have

now

vanished.

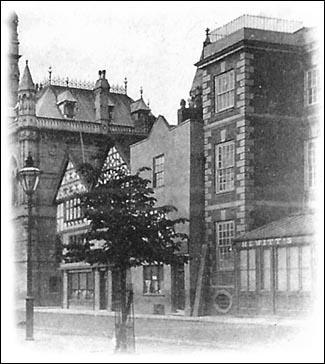

The

large

Georgian

house

on

the

extreme left

was

the

city

residence

of

the

Massey

Family

of

Moston. Next door, the family of Sir Hugh Cholmondeley, who owned a very large amount of property in various parts of Cheshire, owned a grand town house which formed the centre section of the buildings between Princess Street and Hunter Street. This house was in the occupation of the Chamberlaine family in the early years of the 19th century and later in that century the premises were occupied by William Hewitt, a coach builder- you can see the premises with his name above the door on the right of this rare old photograph, which also shows the long-vanished Elephant & Castle Inn next door. (go here to learn much more about this and hundreds more of the lost pubs of Chester). About the year 1900 they were taken over by a similar firm and re-built. They were rebuilt once again on a grander scale in 1913 to a design by Philip Lockwood for the Westminster Coach and Motor Car Works and this remains with us today as the facade of Chester Library. This was, controversially, due to be demolished as part of the Northgate Redevelopment Scheme, the elegant terracotta facade would then have formed an entrance into the promised new public square and a new, brutalist gass-and-steel library was to have been erected where the ghastly Forum Council Offices and Market Hall now stand. All that seems to have changed, however, as money men and politicians play their game. At the time of this most recent re-editing, Summer 2011, the massive shopping development has failed to materialise- and its site has been landscaped to form St. Martin's Park- the cinema remains closed and we still have no theatre or Arts Centre. Our valued library, however, remains for the moment just where it was.

The

site

of the old mansion was replaced in the 19th cenury by a fine building in a similar style which is

now

occupied

by

the Shropshire

Arms public

house and a florist's shop.

The

fine half-timbered

house

to its right was to be demolished shortly after this print was made. Its

last

tenant

was

the

artist

James

Hunter,

who

gave

his

name

to

the

adjoining

lane, Hunter's

Passage-

later widened and known

since the 1890s as Hunter

Street.

In its place rose

the imposing Northgate House, a private residence which was later used as offices and later still as lodgings for the judges at Chester Assizes. This in turn was demolished and the handsome Grade II listed Art Deco Odeon

Cinema was built here in 1936. Before its construction commenced, an archaeological dig took place, conducted by the great Professor Robert Newstead. This unearthed some interesting Roman and medieval remains, some of which were put on show in the upper lounge and may still be seen there today. The

site

of the old mansion was replaced in the 19th cenury by a fine building in a similar style which is

now

occupied

by

the Shropshire

Arms public

house and a florist's shop.

The

fine half-timbered

house

to its right was to be demolished shortly after this print was made. Its

last

tenant

was

the

artist

James

Hunter,

who

gave

his

name

to

the

adjoining

lane, Hunter's

Passage-

later widened and known

since the 1890s as Hunter

Street.

In its place rose

the imposing Northgate House, a private residence which was later used as offices and later still as lodgings for the judges at Chester Assizes. This in turn was demolished and the handsome Grade II listed Art Deco Odeon

Cinema was built here in 1936. Before its construction commenced, an archaeological dig took place, conducted by the great Professor Robert Newstead. This unearthed some interesting Roman and medieval remains, some of which were put on show in the upper lounge and may still be seen there today.

Also soon after the print was made,

the

wooden

stalls

of

the meat

shambles on

the

far

left

of

the

picture

were

replaced

by

a

stone

and

brick

market

building,

shown

in this fine

illustration

of

the

old Exchange.

It

is

recorded

that,

in

1581,

the

city

magistrates

bought

the

old

Shire

Hall

at

the Castle "for

six

Cheshire

cheeses",

and

had

it

moved

to

the

Market

Square,

where

it

was

first

served

as

a

granary,

and

was

then

appropriated

by

the

city's

butchers, becoming

adapted to form the

flesh

shambles.

The

house

on

the

far

right

is the once-grand Folliot

House,

built in 1778 by the merchant W H Folliot, who appears in Cowdroy's Directory in 1789. It later became

for a time the

home

of

the

architect and designer of the Northgate, Thomas

Harrison. Though

now

converted

to

offices (home to the Citizen's Advice Bureau and other social services), closely

hemmed-in

by

commercial

premises and robbed of its extensive gardens,

it is

the

only

building

in

the

illustration

that

remains with us

to

this

day, albeit in a brutally truncated form, as shown by the photographs below...

|

|

|

The picture on the left was taken during the Second World War when when the house served in the unglamorous but vital role of a storage depot for ARP (air raid precautions) equipment such as respirators and waterproof garments. Training exercises for the AFS (Auxilliary Fire Service) volunteer firemen were also carried out here. (The main fire station was a short distance up the street, out of shot to the right. See below..)

At an undetermined date since, the fine old Georgian mansion was unceremonially 'chopped in half'- the bricked-in shapes of former interior windows and doors can still be clearly seen on the blank wall nearest to the camera in the later views. Our middle photograph shows it like this in the late 1960s. Note the changed arrangement of the side windows between this and the modern view. The space between the house and the currently closed-down Odeon Cinema is now occupied by a mundane bookmaker's premises. However, the near future may bring exciting changes to old Folliot House and its surroundings as this artist's impression on the next page shows...

The ancient Pied Bull public house next door looks exactly the same except for the reduction in height of its tall chimney. We will learn more of it and other neighbouring inns in the third part of our wanderings around Northgate Street... The ancient Pied Bull public house next door looks exactly the same except for the reduction in height of its tall chimney. We will learn more of it and other neighbouring inns in the third part of our wanderings around Northgate Street...

Thomas Harrison was a prolific architect here in Chester- in addition to the Northgate, he was responsible for the great Grosvenor Bridge, the rebuilding of the Castle and its (now-demolished) County Gaol, the Commercial Newsrooms at the further end of Northgate Street, the refacing of St. Peter's Church after the removal of the Pentice at the Cross and much else. Elsewhere, his most noted surviving buildings include the Skerton Bridge and the recently-closed County Gaol at the Castle in Lancaster, the Portico Library in Manchester and Europe's first lending library, the Lyceum and the rebuilt tower of the Parish Church of Our Lady & St. Nicolas in Liverpool.

The

attractive

timber

building

next

to

the former Blue Bell

Inn was

built

in

1911

as

a

fire

station,

designed

in the Vernacular Revival style by James

Strong,

a

pupil

of

John

Douglas, complete with oriel windows beneath picturesque overhanging gables- in Chester, even the fire station had to be a half-timbered building!

It was designed to house three horse-drawn fire engines and later, motorised ones such as the example shown in our picture. However, unable to accomodate larger modern appliances, the station

closed

in

1970

and

served

for a while as

retail

premises,

but

has now

been

transformed

into

a

smart French

restaurant.

When the firemen moved to their new station on nearby St. Anne Street, they left behind Jack, the resident ghost. Jack used to be seen sitting on the engines, an old fireman with whiskers, dressed in an old-fashioned uniform and a brass helmet... When the firemen moved to their new station on nearby St. Anne Street, they left behind Jack, the resident ghost. Jack used to be seen sitting on the engines, an old fireman with whiskers, dressed in an old-fashioned uniform and a brass helmet...

An

earlier

fire

station

of

sorts,

known

as

'The Engine

House' existed

further

up

the

road

in

the

late

18th

century.

The

1792

directory

refers

to

it

as "a

neat

building,

with

fluted

columns

and

a

rich

cornice,

of

the

Corinthian

order.

The

fire

engines

are

kept

here

at

the

expense

of

the

Corporation,

and

the

keys

at

the

Exchange

Coffee

House,

also

by

persons

in

different

parts

of

the

city."

Fourty-odd

years

later, Joseph

Hemingway noted: "After

King

Street

on

the

left,

an

open

space,

used

as

a

potato

market,

is

discovered.

At

the

extremity

of

this

area,

a

good

brick

building

has

been

erected,

and

the

upper

part

converted

into

a

reservoir,

which

is

constantly

filled

with

water

to

supply

the

city

with

that

necessary

article,

and

to

be

in

readiness

in

case

of

fire.

The

apartments

beneath

are

occupied

as

depositories

for

the

fire

engines".

We remarked earlier, with reference to Centurion House, that Northgate Street had otherwise largely managed to escape the attention of the planners and developers that have brought (and continue to bring) so much mediocre architecture to our beautiful city centre. On the right we see two views of the section of the street between the two Abbey Gateways, taken in the 1960s and today. The terrace of 19th century houses, whose ground floors were later converted to shops, have been replaced by a brash development of shops and offices by the name of Gateway House.

The University Cathedral Free School also now operates out of this utilitarian building, following the surprise failure of its plan to take up much more prestigious premises in a fine mid-18th century house in nearby Abbey Square (which nontheless continues to feature prominently on the school's website logo..)

More Dodgy Developments

In 2005, the local press reported that the days of the St. Anne Street fire station were apparently numbered as plans were afoot for the building to be demolished- together, scandalously, with the award-winning Northgate Arena next door, a replacement for which was to be built at the Greyhound Retail Park on the edge of the city. On its site it was proposed to erect a Hilton Hotel, of all things, even more 'luxury' apartment blocks- plus an inevitable 'sweetener' in the form of Extra Care housing for the elderly. In 2005, the local press reported that the days of the St. Anne Street fire station were apparently numbered as plans were afoot for the building to be demolished- together, scandalously, with the award-winning Northgate Arena next door, a replacement for which was to be built at the Greyhound Retail Park on the edge of the city. On its site it was proposed to erect a Hilton Hotel, of all things, even more 'luxury' apartment blocks- plus an inevitable 'sweetener' in the form of Extra Care housing for the elderly.

Expecting the worst, Chester's people were pleasantly surprised when our councillors, being advised that the plans were worrying on many counts, wisely rejected the planning application. The plot reared its head once more, however, in November 2007 when aspiring developer, Steeltower Ltd, headed by one Patrick Davies, submitted an 'amended' version of their proposals.

An unconvinced, and unnamed, local developer was quoted in the Chester Chronicle as saying, "I am a bit confused. I don't understand where the land value would be created. How are you going to generate the millions to pay for all these goodies?" (What goodies would they be then, we wondered?)

Concerned local individuals, such as

City Councillor Ruth Davidson and Geoff Alderton, took steps to ensure that the Northgate Arena was protected from predatory attacks such as this by being made a listed building. English Heritage, thought differently however, saying that the building "lacks the high level of architectural quality necessary", that its styling is "typical rather than exceptional" and that "its interior has been compromised by later alterations". We would disagree strongly- and also remind you that these are the people that, just across town, have for years fought tooth and nail to defend a rotting Victorian ex-convent that happens to stand on top of the largest Roman military amphitheatre in Great Britain...

The Northgate Arena stands on the site of the old Northgate railway station which closed in 1969. It was designed by the Building Design Partnership, a design we personally like very much. It is managed by the Chester and District Sports and Recreation Trust (CADSART), a non-profit making charitable trust. In January 2008, it beat over 450 other entrants to be named the best leisure centre in the UK by the Association for Public Service Excellence (APSE). Will this stunning achievement finally put paid to SteelTower's aspirations? Certainly, to the relief of all, nothing more has since been heard from them and a new 'Doubletree by Hilton' hotel has instead been recently opened at the historic Hoole Hall on the edge of Chester. The Northgate Arena stands on the site of the old Northgate railway station which closed in 1969. It was designed by the Building Design Partnership, a design we personally like very much. It is managed by the Chester and District Sports and Recreation Trust (CADSART), a non-profit making charitable trust. In January 2008, it beat over 450 other entrants to be named the best leisure centre in the UK by the Association for Public Service Excellence (APSE). Will this stunning achievement finally put paid to SteelTower's aspirations? Certainly, to the relief of all, nothing more has since been heard from them and a new 'Doubletree by Hilton' hotel has instead been recently opened at the historic Hoole Hall on the edge of Chester.

A second threat to the Northgate Arena occured soon after when a madcap plot to relocate West Cheshire College to its car park was announced (together, of course, with the flogging off of its original attractive site in Handbridge for housing). After massive objections and the wasting of lots more money and words, this idiocy, too, thankfully came to nothing.

Most recently, in September 2010, we're starting to learn of yet another plan to provide "state of the art" leisure facilities elsewhere in the city and get rid of the "ageing" Arena (an ironic description in a city of truly 'ageing' buildings- are they therefore for the chop too? Nothing would surprise us). These include such indispensables as a 'regional diving centre' and a 'centre for swimming development', whatever that may be. How have we managed without so far? Some of the proposed new developments have been publicised as being "in the green belt", as if that was somehow a good thing.

A sweetener to all this would be the setting aside of money for the redevelopment of the much-loved John Douglas City Baths in Union Street- unlike the Arena, a listed building. Note the term 'redevelopment' as opposed to 'restoration'- another one for those who care about this city to keep a watchful eye upon...

A great deal of local upset has recently been caused by the appearance of some truly awful new buildings in the immediate vicinity of the Arena, most notably a vast, ugly and inappropriately-situated Travelodge hotel. Can we assume that the Arena's site has been quetly earmarked for more of the same, God help us? Watch this space.

• A stunning panoramic movie of Northgate Street may be seen at Chester 360º

On to part II of our exploration of Northgate Street...

Curiosities from Chester's History no. 1

(To help put the events listed here and on the following pages into context,

we have also included the reigns of the Kings and Queens of England and a

selection of major world events- these latter are shown in blue). Links to further reading are also provided.

- BC

55

First,

short-lived,

Roman

expedition

to

Britain

by Julius

Caesar.

- BC 54 Caesar's second invasion of Britain. British forces led, this time, by Cassivellaunus. Despite early Roman advances, the British continued to effectively harass the invaders. A deal struck with the Trinovantes, tribal enemies of Cassivellaunus, and the subsequent desertion of other British tribes, finally guaranteed the Roman victory. Caesar's first two expeditions to Britain were only exploratory in nature, and were never intended to absorb Britain into the Roman sphere at that time.

- 54 BC-43 AD - Roman influence increases in Britain as a direct result of trade and other interaction with the continent and despite the absence of a military presence.

- 7BC Birth of Jesus Christ in Bethlehem

- AD 5 Rome acknowledges Cunobelinus (Shakespeare's Cymbeline), King of the Catuvellauni, as king of Britain.

- AD 43 The Romans, under Aulus Plautius, land at Richborough in Kent for a full-scale invasion of the island. In the same year, the

Emperor Claudius visited

the

site

of

Chester

when

campaigning

against the Welsh.

London

was

founded

and

the

British

under Caractacus were

defeated

at

the

Medway.

- AD

45

St.

Paul

sets

out

on

his

missionary

travels

- AD

48

The

Roman

General Ostorius

Scapula made

camp

here

as

part

of

his

expedition

into

the

territory

of

the Deceangli (N E

Wales).

They appear to have surrendered with little resistance, unlike the Silures and the Ordovices who put up a long and bitter resistance to Roman rule. The

Romans

learned

the

use

of

soap

from

the

Gauls

around

this

time.

- AD

58-60 Suetonius

Paulinus attacks

the

Ordovices

and

decimates

the Druids on the island of

Anglesey.

- AD 61 Boudica, queen of the Iceni, led her uprising against the Roman occupiers, but is defeated and killed by the Roman governor, Suetonius Paulinus.

- AD 63 Joseph of Arimathea came to Glastonbury on the first Christian mission to Britain.

- c.

AD

70

The

Legion

II Adiutrix

Pia

Fidelis ('dutiful

and

faithful')

were

posted

to

Britain

and

within

four

years

had

commenced

the

construction

of

their

fortress

in

timber

and

turf

at

what would become the future site of Chester. AD 79 is generally given as the 'official' date for this. Revolt

of

the

Jews

against

Rome;

Jerusalem

captured

and

destroyed.

- c.AD 75-77 The Roman conquest of Britain is complete, as Wales is finally subdued; Gnaeus Julius Agricola is imperial governor (to AD 84).

- AD 79 Eruption of Mount Vesuvius on August 23-24. Pompeii destroyed. The Colloseum opens in Rome.

- AD

86

Legion

II

are

posted

to

the

Danube

and

replaced

in

Chester

by

XX

Legion Valeria

Victrix ('strong

and

victorious')

under

Julius

Agricola.

They

were

to

remain

here

until

until

c.

AD

395.

(The

last

Roman

troops

left

Britain

in

436)

- c.

AD

102

The fortress

and amphitheatre rebuilt

in

high-quality masonry.

- c AD 120-165 Much of the XXth Legion were posted north to build and garrison the Hadrianic and Antonine frontiers of the province; a skeleton garrison remain in Deva

- c AD 160 A major rebuilding and expansion of the fortress commences upon the XXth Legion's return from the north.

- AD 209 St. Alban, first British martyr, was killed for his faith.

- AD 311 The Edict of Toleration proclaimed at Milan, in which Christianity is made legal throughout the empire. In 314, three British bishops, for the first time, attend a continental church gathering, the Council of Arles.

- c AD 380 The Romans abandon Deva as

Magnus Maximus takes all of the Legions out of Britain as part of a revolt against Rome. They never return.

- c 475 In legend, Arthur fights his ninth battle at 'the City of the Legions'- likely Chester.

476

End

of

the

Western

Roman

Empire.

First

Shinto

shrines

appear

in

Japan. 476

End

of

the

Western

Roman

Empire.

First

Shinto

shrines

appear

in

Japan.

- c AD 500-600 Chester forms part of the Welsh kingdom of Powys.

- 537 Arthur,

King

of

the

Britons,

reputedly

killed

at

the Battle

of

Camlan

- c AD 600 Chester and the surrounding area absorbed into the English kingdom of Mercia.

- c.

603 Augustine, the first Archbishop of Canterbury, meets

with

Celtic

bishops "in

the

city

of

the

Legions".

The Annales

Cambrie (Annals

of

Wales)

mention

a

Synod

of

The

City

of

the

Legions

in

a

year

which

might

be

603

or

606 (they

follow

an

eccentric

chronology

all

of

their

own,

and

it's

often

difficult

to

place

an

event

into

the

correct

calendar

year).

This

Synod

is

the

one Bede mentions

when

describing

how

the

British

church

rejected

Saint

Augustine's

authority.

In

Bede-

who

refers

to "The

City

of

the

Legion,

which

is

called

Carlegion

by

the

Britons

and

Legacaistir

by

the

English"-

this

then

becomes

the

cause

of

the Battle

of

Chester (in

the

year

613

or

616),

when

the

monks

from

Bangor-is-y-Coed (Bangor-on-Dee),

who

had

prayed

and

chanted

in

support

of

the

enemy,

were

slaughtered

by

the

pagan Aethelfrith (reigned

592-616).

- 620 Edwin,

King

of

Northumbria,

Deira

and

Bernicia

(616-632AD)

gathered

a

large

fleet

at

Chester

with

which

he

attacked

the

isles

of

Anglesey

and

Man,

capturing

both

of

them.

- 622

Mohammed's

flight

from

Mecca

to

Medina.

Year

one

in

the

Moslem

calendar

- 660 King Wulphere founds a church and convent dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul on the site of the present Cathedral

|

![]() You're proud to be in business in Chester so tell the world-

You're proud to be in business in Chester so tell the world-

elcome! We

commence

our exploration of Chester's ancient city walls by

standing

here, on

top

of

the Northgate.

elcome! We

commence

our exploration of Chester's ancient city walls by

standing

here, on

top

of

the Northgate.