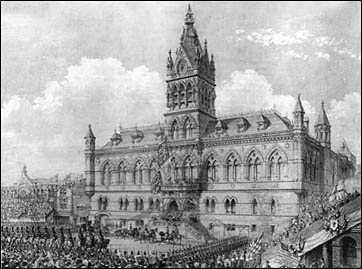

rominent

in

Chester's

Market

Square, and

seen here in a photograph taken on a snowy day in 1917,

is the Town

Hall,

which

was

built

in

1864-9

in

an interpretation of the

Gothic

style

of

the

late

13th

century

by William

Henry

Lynn (1829-1915) of

Belfast,

to

replace

the

17th

century Exchange which

stood

in

the

middle

of

the

square

before

burning

down

in

1862. rominent

in

Chester's

Market

Square, and

seen here in a photograph taken on a snowy day in 1917,

is the Town

Hall,

which

was

built

in

1864-9

in

an interpretation of the

Gothic

style

of

the

late

13th

century

by William

Henry

Lynn (1829-1915) of

Belfast,

to

replace

the

17th

century Exchange which

stood

in

the

middle

of

the

square

before

burning

down

in

1862.

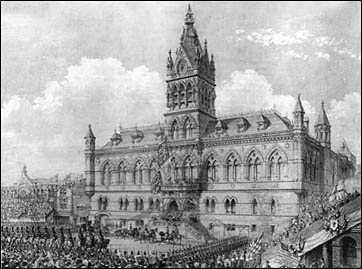

Lynn had been apprenticed to the architect Charles Lanyon in Belfast in 1846, serving as clerk of works on Lanyon's Queen's College and County Court House. In 1854 he was taken into partnership by Lanyon and remained with him until 1872 when the firm was dissolved and Lynn set up practice on his own. He was a prolific designer with an eclectic taste and a scholarly interest in historic styles, at first mainly medieval but later also classical.

Referring back briefly to the old Exchange, you

can

see

some

fine

engravings

of it-

and

also

a

very

early

photograph

by Henry

Fox

Talbot- here. And here are

some

contemporary

photographs

of

the grand

Victorian

replacement we are to discuss now.

The

design of the new

building

came about as the result of a competition which specified that the new Town Hall should be "substantial and economical rather than ornamental... and costing no more than £16,000".

Its design was

inspired

by

the

beautiful medieval Cloth

Hall in

Ypres,

Belgium. Finished in 1304, this was

the

most

impressive

commercial

building

of

medieval

northern

Europe and leading example for the Flemish profane building style.

During the First World War, it was completely destroyed, with the exception of the lower portion of the belfry and a few pieces of wall on the west wing, but was later lovingly rebuilt in its original form.

Lynn, seemingly ignoring the Corporation's request for an 'economical' building, incorporated all manner of fancy Gothic features into his design and utilised two types of local sandstone, pink and grey.

Construction was considerably delayed when the stonemasons, for a variety of reasons, fell out with the management, resulting in their going on strike for nine months. Nontheless, the new Town Hall was eventually opened, amid great pomp and ceremony in October 1869 by the Prince of Wales- the future King Edward VII.

Preparations for the royal visit were discussed at great length by the Corporation and, aware that the nation's eyes would be upon them, it was agreed that no cost was to be spared to make the event a success. Roads were dug up to lay gas pipes to provide the necessary extra illumination- the Prince was due to arrive as dusk fell- and three large viewing galleries with room for 2,500 spectators were erected in the Market Square. To preserve public order, an additional 500 police and 22 detectives were hired and fireworks for a grand display at the Roodee, Chester's ancient racecourse, were ordered. Houses and shops throughout the city were repainted and the Eastgate railings were painted bright blue tipped with gold. Preparations for the royal visit were discussed at great length by the Corporation and, aware that the nation's eyes would be upon them, it was agreed that no cost was to be spared to make the event a success. Roads were dug up to lay gas pipes to provide the necessary extra illumination- the Prince was due to arrive as dusk fell- and three large viewing galleries with room for 2,500 spectators were erected in the Market Square. To preserve public order, an additional 500 police and 22 detectives were hired and fireworks for a grand display at the Roodee, Chester's ancient racecourse, were ordered. Houses and shops throughout the city were repainted and the Eastgate railings were painted bright blue tipped with gold.

Upon arrival at Chester Station, the Prince was met by Earl Grosvenor and the Prime Minister, William Gladstone. The party travelled by coach from there, passing en route under a grand ceremonial arch which had been constructed on City Road (itself laid out only five years earlier) in half-timbered 'Chester' style, to his accomodation at the Grosvenor Hotel in Eastgate Street.

On the following afternoon, to the acclamation of the assembled crowds, the Prince officially opened the Town Hall and this was followed by a grand dejeuner and a ball in the evening, attended by the great and good of the city and county.

The following day, the Cheshire Observer observed that "the city may now lay aside its toys, take down the bunting, remove the barriers and arches and once more return to its ordinary, everyday life". The following day, the Cheshire Observer observed that "the city may now lay aside its toys, take down the bunting, remove the barriers and arches and once more return to its ordinary, everyday life".

The event attracted national press coverage; the engraving on the left, showing the crowds before the great new building, appeared soon after the event in the Illustrated London News. The visitor, looking upon the same location today, would note no noticeable change to the Town Hall itself but would note the addition of The Forum, a mediocre jumble of modern structures to the left of the picture- a site at the time occupied by the venerable White Lion Inn and a number of other hostelries and later the ornate- and still much missed- Market Hall.

The cost of building the Town Hall somewhat overran the original budget of £16,000- eventually costing almost £50,000- around two and a half million pounds in today's money. The cost of building the Town Hall somewhat overran the original budget of £16,000- eventually costing almost £50,000- around two and a half million pounds in today's money.

On the left we see both faces of the commemorative medal that was issued at the time and given to all involved in the building and opening of the Town Hall. (Thanks to Keith Hobbs for the loan of this interesting piece of Chester history).

When the building was planned, the question of adding a clock arose and a fine example actually considered, which had originally been intended for Woolwich Arsenal. The mighty mechanism was described as "more powerful than Big Ben" but would require one hour's winding each and every day. In the face of the rapidly over-running budget, the costs of purchase, installation and maintainance of the clock were considered extravagences too many and the idea was scrapped. Space for a future installation was, however, provided in the Town Hall's 160 foot tower and the clock we see today was commissioned as recently as 1979 and installed in 1980 to commemorate Chester's 1900th anniversary. It is curious to note that only three clock faces look out from the four-sided tower- the west side, facing towards neighbouring Wales, has none, giving rise to a cynical local saying that "Chester people wouldn't give the time of day to the Welsh"!

The City Council meet in a grand chamber on the first floor which had to be rebuilt by the prolific local architect Thomas Lockwood (possibly best remembered as the designer of the Grosvenor Museum and the much-photographed ornate buildings at the Cross) - after a disastrous fire which completely destroyed it in 1897. Today, as well as the affairs of local government, the Town Hall is used for concerts, receptions, exhibitions and the like- and you can even get married here! The ornate interior is well worth viewing. The City Council meet in a grand chamber on the first floor which had to be rebuilt by the prolific local architect Thomas Lockwood (possibly best remembered as the designer of the Grosvenor Museum and the much-photographed ornate buildings at the Cross) - after a disastrous fire which completely destroyed it in 1897. Today, as well as the affairs of local government, the Town Hall is used for concerts, receptions, exhibitions and the like- and you can even get married here! The ornate interior is well worth viewing.

A major programme of restoration was embarked upon in early Summer 2008 and, for many months, the exterior was shrouded in a great mass of scaffolding. The stonework was cleaned and pointed and guttering and roofs repaired, and, now the scaffolding has been removed, this handsome building is looking better than it has done in years. A major programme of restoration was embarked upon in early Summer 2008 and, for many months, the exterior was shrouded in a great mass of scaffolding. The stonework was cleaned and pointed and guttering and roofs repaired, and, now the scaffolding has been removed, this handsome building is looking better than it has done in years.

Two stunning

panoramic movies of the interior of Chester Town Hall may, along with much else, be seen at the excellent Chester 360°.

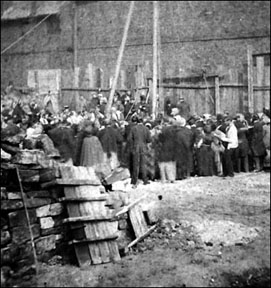

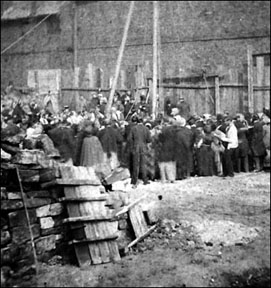

Right: a rare image of the laying of the Town Hall foundation stone in October 1865.

Chester's main police station was situated on the Town Hall's ground floor until 1967, when its replacement was opened on a prime site opposite the Castle. (This huge and unsightly structure was thankfully demolished in 2006- you can see some pictures and learn a little about it in our chapter about the Roodee). The old police station's cells still exist, however; in April 1966, the infamous moors murderers, Ian Brady and Myra Hindley were held here before facing trial at the Chester Assizes in the Castle. Whether connected or not, some have claimed to have felt an 'evil presence' about the old cells; lights are said to switch on and off for no reasson and a mysterious 'figure in brown' has occassionally be seen wandering about...

Since Chester Police relocated to their new HQ, out of the city centre in Blacon, (the County police moved too, to a new HQ in Winsford) a small station has been re-established in its original location, accessible from the Princess Street side of the Town Hall.

At

the

north

end

of

the

square stands

the

handsome

1936

Art

Deco Odeon

Cinema by

Harry

Weedon-

one

of

numerous

provincial

'picture

palaces'

designed

by

him.

Most

Odeons

of

the

period

were

faced

with

ceramic

tiles,

but, in keeping with the surrounding architecture,

a

more

traditional

red

brick

facing was

used

on just two, here

in

Chester and at its sister house, which it closely resembles, in the lovely city of York.

The

upstairs

foyer

housed

an

interesting

display

of

Roman

and

medieval

artifacts

discovered

during

its At

the

north

end

of

the

square stands

the

handsome

1936

Art

Deco Odeon

Cinema by

Harry

Weedon-

one

of

numerous

provincial

'picture

palaces'

designed

by

him.

Most

Odeons

of

the

period

were

faced

with

ceramic

tiles,

but, in keeping with the surrounding architecture,

a

more

traditional

red

brick

facing was

used

on just two, here

in

Chester and at its sister house, which it closely resembles, in the lovely city of York.

The

upstairs

foyer

housed

an

interesting

display

of

Roman

and

medieval

artifacts

discovered

during

its

A few years ago, the owners of this, the very last of our once-numerous city centre picture palaces, declared it to be no longer profitable and- to the distress of Chester's people, sold it to a developer. Unlike York, where their Odeon was rapidly acquired by their council and re-opened as a cinema- the new owners declared their intention in converting ours into a nightclub of all things. By a couple of years later, October 2009- and despite the continuing demand of local people for the building to be re-opened, nothing had been achieved, save for our councillors' wise decision to refuse permission for the nightclub and its subsequent dropping by the owners and the addition of some jolly posters advertising 'Petal Power: Chester in Bloom', 'The Northgate Quarter' and suchlike ironies being stuck onto its decaying facade.

Eventually, in September 2011, the building was finally re-acquired by the local authority and soon after it was announced that it will indeed become the home of Chester's new theatre. Whether there will also be room for a cinema as well is currently unknown. Eventually, in September 2011, the building was finally re-acquired by the local authority and soon after it was announced that it will indeed become the home of Chester's new theatre. Whether there will also be room for a cinema as well is currently unknown.

On the right we see one of the 'artist's impressions' of the completed project that appeared in the ages of the local press around this time. On the far right is the 18th century Folliot House and the space between it and the Odeon proper, currently occupied by a mundane bookmaker's premises, has been replaced by a large glass structure.

In the 1990s and the coming of pedestrianisation to most of Chester city centre, there was a spirited debate regarding Northgate Street, which was not at that time pedestrianised despite many people believing it should have been. Two decades later with the advent of the One City Plan for Chester's future development, the debate has reared its head once again

and the majority of the area's traders and residents have joined together to demand that this lovely and historic thoroughfare should also enjoy the numerous, proven benefits of being traffic-free. Despite traffic and other authorities unsurprisingly claiming that such would be impossible, the above illustration clearly shows people relaxing in what appears to be a pleasant, car-free plaza! So who knows. Watch this space for news...

Find out more of our splendid and much-missed Odeon and of its future in our History of the Cinema in Chester.

On the right we see a rare photograph of the 18th century Northgate House which was demolished to make way for the Odeon. It once offered lodging to the judges presiding over the Chester Assizes at the Castle. It may be seen again in several old pictures of Chester's former town hall, The Exchange..

Across Northgate Street from the Odeon, the ground floors of the buildings between the Little Abbey Gateway (see below) and the Northgate are all converted into shops but, looking up (which few people do), it is evident that the southern range were once gracious Georgian mansions housing affluent families. The spout head on the one nearest to the gateway bears the date 1749. Another, nearer to the gate- and the location of the author's studio and gallery, The Handel's Court Gallery, says 1799. Across Northgate Street from the Odeon, the ground floors of the buildings between the Little Abbey Gateway (see below) and the Northgate are all converted into shops but, looking up (which few people do), it is evident that the southern range were once gracious Georgian mansions housing affluent families. The spout head on the one nearest to the gateway bears the date 1749. Another, nearer to the gate- and the location of the author's studio and gallery, The Handel's Court Gallery, says 1799.

Opposite the Town Hall may be observed a great, weathered sandstone archway giving access to the elegant Abbey Square. This is the 14th century Abbey Gateway with once gave access to the precincts of Chester Abbey but now to the elegant Abbey Square, which was developed here, "in the London fashion" in the 18th century. learn more about the Gateway and Abbey Square here. Visit also our gallery of pictures of the Gateways.

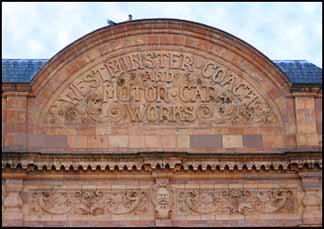

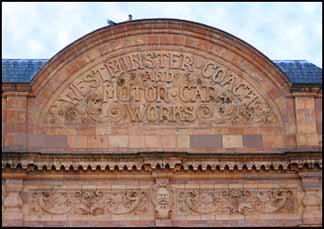

Across from these, and a

little

further

along

the

square

is

the

elaborately-moulded

terracotta

and

red

brick

facade

of Chester

Library which

moved

here

from

its

now-demolished original

home

in

St. John

Street.

It

had

been

built

in

1913

to

a

design

by the Scottish architect Philip

H Lockwood for

the

Westminster

Coach

and

Motor

Car

Works,

serving

as

a

coachbuilders

and

motor

showroom.

From

1973-79

it

housed

a

lively

arts

centre,

'The

Chester

Arts

&

Recreation

Trust'.

When

the

building

was

converted

to

house

the

library,

which

was

built

in

1981-4,

retaining

the

original

facade,

a

replacement

for

the

arts

centre

was

promised

but

never

materialised

and,

three decades

later,

studio

and

gallery

facilities

are

still

sorely

needed

by

Chester's

community

of

creative

artists.

You

may

be

interested

in these pictures

of

the

changing

face

of

the

Chester

Market

Hall

and this traffic-free

view

of

the

square

as

it

appeared

at

the

start

of

the

20th

century...

In

April

1998,

we

heard

the

first

of

a

city

council

plan

to

"Improve

the

layout

and

appearance

of

Town

Hall

Square

and

its

surroundings"

and

three

years

later,

during

the

Summer

of

2001,

news

started

to

appear

in

earnest

about

their

radical

redevelopment

proposals

in

partnership

with

a

company

called London

&

Amsterdam

Developments for

the

entire

area

between

here

and

the

Inner

Ring

Road.

Information

about

the

so-called Northgate

Development

Proposals and their sponsors ING having

grown

considerably,

we

have

now

given

them

their

own

here(which is sorely in need of an update! Enough to say that, as of this update of November 2011, nothing has been built and the land has been laid out as a temporary park). Information

about

the

so-called Northgate

Development

Proposals and their sponsors ING having

grown

considerably,

we

have

now

given

them

their

own

here(which is sorely in need of an update! Enough to say that, as of this update of November 2011, nothing has been built and the land has been laid out as a temporary park).

One

much-discussed

change that has taken

place

in

Northgate

Street,

however,

was

the

addition,

in March

2001,

of

a

contra-flow cycle

lane running

from

the

Odeon

to

the

Northgate

in

order

to

allow

cyclists

to

exit

the

city

centre

against

the

flow

of

one-way

traffic

in

a

northerly

Upon introduction,

the

scheme

produced

a

storm

of

criticism

from

local motorists,

traders,

councillors

and

even the

police,

who

declared

that

the

lane

would

prove

an

obstruction

to

delivery

vehicles

and

actually

be dangerous to

those

cyclists

foolish

enough

to

use

it.

The

police

claimed

it

posed "an

unacceptably

high

risk"

and

one

councillor,

Neil

Fitton,

branded

it

"irresponsible"

and

feared

cyclists

would

be

forced

into

the

path

of

oncoming

traffic.

The

road

is

currently

used

by

around

4,000

vehicles

per

day,

mostly

slow-moving

but

including

a

number

of

large

delivery

vehicles.

Only

time

will

tell.

This

writer

uses

the

lane

often

and

encounters

no

problems

at

all.

The

lane

is

hardly

attractive

but

seems

well

planned

and

allows

ample

room

for

all

responsible

users

of

the

street.

The

scheme

was evaluated

over its first

12

months

but has now

become

a

permament

feature

of

the old Via Decumana..

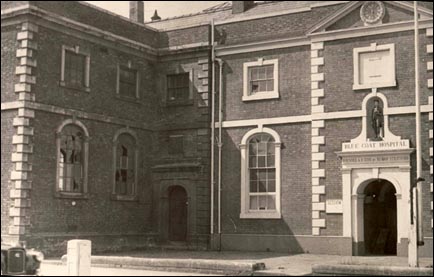

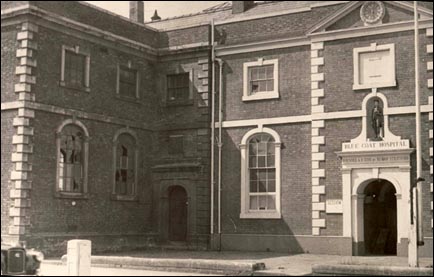

A brief history of the Bluecoat (updated August 2014)

Back

atop

the

Northgate

and

standing

with

our

backs

to

the

city,

across

the

spectacular

canal

cutting

we

see

on

our

left

the Bluecoat

School,

the

first

charity

school

built

outside

London

by

the Society

for

the

Promotion

of

Christian

Knowledge.(The

SPCK

still

exists

today

of

course,

and

until recently maintained

a

bookshop

in

nearby

St. Werburgh

Street). Back

atop

the

Northgate

and

standing

with

our

backs

to

the

city,

across

the

spectacular

canal

cutting

we

see

on

our

left

the Bluecoat

School,

the

first

charity

school

built

outside

London

by

the Society

for

the

Promotion

of

Christian

Knowledge.(The

SPCK

still

exists

today

of

course,

and

until recently maintained

a

bookshop

in

nearby

St. Werburgh

Street).

Architectural

critic

and

author Nikolas

Pevsner was

rather

unkind

about

the

building:

"It

has

all

the

usual

ingredients,

but

somehow

the

composition

seems

lame".

We

find

it

difficult

to

agree

with

him,

and

here

is

a

photograph

of

the

Bluecoat

looking

gorgeous

in

the

Winter

sunshine.

It

is

interesting

to

compare

it

with

the

very

similar

Bluecoat

building

in Liverpool,

which

now

serves

as

an

excellent

arts

centre-

sadly

an

unknown concept

here

in

Chester.

Behind

the

Bluecoat,

and

reached

by

way

of

its

main

entrance,

are

a

charming

group

of almshouses built

around

a

central

courtyard- of which more later.

They

were

also

rebuilt

in

1854,

but

are

historically

linked

to

a

much

older

institution

that

formerly

stood

here,

the Hospital

of

St John

the

Baptist, the Sigillum Hospitalis Sancti Iohannus Baptiste Cestrie,

founded

around the year 1190 by

Randal Blundeville,

Earl of Chester and Richmond and Duke of Brittany.

He gave the site in free alms and free of all services except the reception and care of the poor and ordered that the brothers of the hospital who travelled through Cheshire preaching and collecting alms should be honourably treated. The Earl's grant was made to the Virgin and All Saints but within a few years the hospital had acquired its dedication to St. John the Baptist and was usually known as the Hospital of St. John without the North Gate.

In the 13th century the hospital community, apart from the poor and the sick, evidently consisted of a prior, brethren, and lay servants living under religious rule.

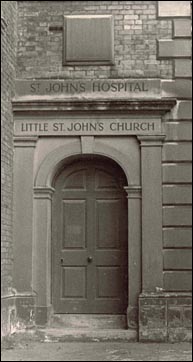

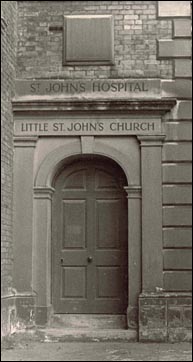

Around 1240 the brethren were given permission to build a chapel "beyond the Foregate" (actually the Northgate) and within the precincts of the hospital, known

as

St. John

Without

the

Northgate or

Little

St. John

to

distinguish

it

from St. John's

Church located

outside

the

SE

corner

of

the

city

walls

close

to

the

Roman amphitheatre.

The extensive privileges given to the hospital by Ranulph III were a potential cause of conflict and early in its history arrangements were made to protect the interests of the existing churches in Chester. It was agreed between the brethren of the hospital and the Abbot of Chester Abbey that all servants of the hospital wearing secular clothes, apart from the gardener, the porter (claviger), the Prior's groom, and the woman who attended the sick, were to pay tithes and offerings to the mother church of St. Werburgh, as were those staying in the hospital and wearing secular clothes. Any servants engaging in trade were also to pay tithes and offerings to the mother church. Strangers and travellers, however, were allowed to receive the Sacraments and make offerings at the hospital church. A similar agreement concerning burial rights was reached in the early 13th century with the Abbot and Convent of St. Werburgh's and the Dean of St. John's. The brethren of the hospital were allowed to have a graveyard to bury the poor who died there and also men and women in confraternity with the hospital who had worn its habit in good health and for at least eight days. The extensive privileges given to the hospital by Ranulph III were a potential cause of conflict and early in its history arrangements were made to protect the interests of the existing churches in Chester. It was agreed between the brethren of the hospital and the Abbot of Chester Abbey that all servants of the hospital wearing secular clothes, apart from the gardener, the porter (claviger), the Prior's groom, and the woman who attended the sick, were to pay tithes and offerings to the mother church of St. Werburgh, as were those staying in the hospital and wearing secular clothes. Any servants engaging in trade were also to pay tithes and offerings to the mother church. Strangers and travellers, however, were allowed to receive the Sacraments and make offerings at the hospital church. A similar agreement concerning burial rights was reached in the early 13th century with the Abbot and Convent of St. Werburgh's and the Dean of St. John's. The brethren of the hospital were allowed to have a graveyard to bury the poor who died there and also men and women in confraternity with the hospital who had worn its habit in good health and for at least eight days.

Besides granting the site of the hospital and taking it under his special protection, Ranulph Ill agreed to maintain three beds for the poor and infirm at the rate of one penny a day in alms for each pauper; these alms of £4 11s a year were continued by the Crown after 1237 and were still being paid in the 16th century.

By the early 14th century the hospital had endowments worth £33 4s 10p a year. Members of the leading families of Chester made gifts to the hospital. However, much of the property lying outside Chester was alienated in return for small rent charges, doubtless for reasons of convenience. An inquiry in 1316 found that this short sighted policy had been carried out by successive priors and, in 1311 the master, William de Bache, was said to "have so impoverished the hospital as to impair its work of mercy and hospitality" and was removed from office.

A succession of inquisitions held between 1311 and 1341 revealed that the administration of the hospital had undergone a transformation similar to that of other hospitals at the period and was controlled by a master rather than a prior and chapter of brethren. Three chaplains celebrated there daily- two in the church and one in the hospital before the feeble and infirm inmates.

The hospital was to take in as many poor and sick as possible but thirteen beds were to be kept ready for the

housing

of

"thirteen

poore

and sillie citizens,

whereof

each

shall

have

for

daily

allowance

a

loaf

of

bread,

a

dish

of

pottage,

half

a

gallon

of

competent

ale

and

a

piece

of

fish

or

flesh,

as

the

day

shall

require". The hospital was to take in as many poor and sick as possible but thirteen beds were to be kept ready for the

housing

of

"thirteen

poore

and sillie citizens,

whereof

each

shall

have

for

daily

allowance

a

loaf

of

bread,

a

dish

of

pottage,

half

a

gallon

of

competent

ale

and

a

piece

of

fish

or

flesh,

as

the

day

shall

require".

In 1316 the hospital was unwisely transferred to the guardianship of Birkenhead Priory, which impoverished by the cost of providing hospitality to travellers crossing the River Mersey to Liverpool. The priory took over the responsibility of maintaining the services and almsgiving of the hospital on inadequate and diminished resources and the annual revenues of the hospital declined.

Right: some of the almshouses still in use behind the old Bluecoat School

Then, in June 1341 the Black Prince took the hospital with its estates into his own hands and an inquiry was ordered into its government. Before the inquiry was held the custody of the hospital, which was reported to be "burdened with heavy charges and suffering from misrule", was given to a royal clerk. The inquiry found that the church, chapel, and hospital buildings were not adequately roofed and that two large houses had collapsed from age and lack of repair.

In the later Middle Ages most of the masters must have been non-resident with livings and official duties elsewhere and it became the practice of such masters to appoint chaplains to administer the hospital for them. In 1414 Henry V confirmed the privileges of the hospital: its tenants enjoyed freedom from jury service and suit of court in the city and county and freedom from local tolls and taxes. Nevertheless, the hospital remained impoverished and was exempted from taxation in the later 15th century. In the later Middle Ages most of the masters must have been non-resident with livings and official duties elsewhere and it became the practice of such masters to appoint chaplains to administer the hospital for them. In 1414 Henry V confirmed the privileges of the hospital: its tenants enjoyed freedom from jury service and suit of court in the city and county and freedom from local tolls and taxes. Nevertheless, the hospital remained impoverished and was exempted from taxation in the later 15th century.

There were complaints from the city authorities in the 1520s that, in the absence of the master, the hospital's constitution was not being properly observed and, in particular, "foreign people" were being given places.

Left: Bishop Stratford and the Bluecoat in a stained glass window in the cloisters of Chester Cathedral

The role of the hospital in housing the infirm poor of the city of Chester doubtless saved it from dissolution under the Henry VIII's Act of 1547 and the commissioners who visited Chester in May 1553 to list church goods found "nothing worth selling".

In the latter half of the 16th century many of the hospital's lands were leased out for very long periods by a succession of unscrupulous masters and in 1601 a commission was appointed to visit and reform the hospital. They found that the master, Richard Young, had not visited the hospital for over three years as he had been imprisoned for debt in Chester Castle. He was immediately removed from the office of master.

In February 1644 all the stone buildings of the hospital and chapel and the surrounding wall were demolished so

as

not

to

provide

cover to the

Parliamentary

forces

then

besieging

the

city. No trace is left of the original hospital church or other buildings and nothing, sadly, is known of their appearance.

But

for

the

Civil

War-

and

allowing

for

the

philistinism

of

modern

developers-

Chester

would

doubtless

today

be

blessed

with

considerably

more

ancient buildings

outside

the

Walls,

as

may

be

plainly

seen

by

the

melancholy

account

written

after

the

siege

by Randle

Holme

III.

In June 1658 Oliver Cromwell granted the site and the lands of the hospital and the office of keeper or warden to the town corporation. The mayor was to act as warden and use the revenues to relieve the poor and rebuild the hospital. At the Restoration the corporation petitioned the Crown for the continuation of the arrangement to relieve the increasingly numerous poor in the city but the wardenship was granted for life to Colonel Roger Whitley who is said to have rebuilt the hospital. In 1685 the corporation secured the reversion of the wardenship with all the hospital lands but, although Whitley died in 1697, the corporation did not obtain the hospital seal and records until 1703. In June 1658 Oliver Cromwell granted the site and the lands of the hospital and the office of keeper or warden to the town corporation. The mayor was to act as warden and use the revenues to relieve the poor and rebuild the hospital. At the Restoration the corporation petitioned the Crown for the continuation of the arrangement to relieve the increasingly numerous poor in the city but the wardenship was granted for life to Colonel Roger Whitley who is said to have rebuilt the hospital. In 1685 the corporation secured the reversion of the wardenship with all the hospital lands but, although Whitley died in 1697, the corporation did not obtain the hospital seal and records until 1703.

In 1717 fine new buildings were erected on the site including the Bluecoat Charity School facing Northgate Street. The public subscription towards its erection had actually commenced some years earlier, in 1700 under the auspices of Dr. Nicholas Stratford, who was Bishop of Chester 1689-1707. He had

been

dead

for

ten

years

when

the

the

school

was

eventually

built.

The

25

boys

attending

the

school

as

boarders

were

clothed

in

blue

and

educated

at

the

expense

of

the

charity

and

120

others,

known

as Green

Caps were

taught

there

as

day-scholars.

A new chapel was built in

the

southern

wing- closest to the Northgate- commemorated

today by

the

little

cross

and

bell

which

still

exist

on

its

roof.

One surprising aspect of the training of the young men at the Bluecoat School is discussed in the following extract from a letter from a Mr. Samuel Derrick, Master of the Ceremonies at Bath, "to the Right Hon. Lord Southwell, Chester, July 17,1760”...

“Your worship is so well acquainted with the city of Chester, that it would be ridiculous in me to give you any account; yet in this ancient city, there is an article, my lord, which you will permit me to mention, as it may probably have escaped your notice: it is a charity-school absolutely appropriated io the education of jockeys.

The truth of the matter is this: there is a charity-school without the North- gate, well-endowed, having a large fund, intended by the donor to be laid out in putting the children here educated, at a certain age, to trades. Some years ago it was usual to bind them out to the tradesmen and artificers of Chester; and consequently, when out of their time they were admitted freemen, and had a right to vote in the election of members to represent the town in Parliament; but it having often happened that many of them were too honest, or too obstinate, to receive directions in that material point from any superior but their own consciences, the practice of making them saucy rebellious tradesmen has been discontinued, and they are put out to horse-hirers and jockeys, not free of the city. This account I had from an old ill-natured fellow, who hates all mankind, and fattens on scandal, sarcasm, and ridicule”.

Around the same time that the school was founded, to its rear were raised six single storeyed almshouses. The almswomen, or "chapel-yard widows", were supported from the revenues of the hospital lands but the bulk of the considerable income of the hospital was diverted by the corporation for other purposes. Indeed, in 1835 it came to light that the corporation had grossly mismanaged the property- only £85 of the annual income of £600 was applied to the purposes of the hospital- including the repair of the buildings, the stipend of a chaplain, and small allowances to the inmates. An action alleging misappropriation of funds was brought against the corporation in Chancery. Around the same time that the school was founded, to its rear were raised six single storeyed almshouses. The almswomen, or "chapel-yard widows", were supported from the revenues of the hospital lands but the bulk of the considerable income of the hospital was diverted by the corporation for other purposes. Indeed, in 1835 it came to light that the corporation had grossly mismanaged the property- only £85 of the annual income of £600 was applied to the purposes of the hospital- including the repair of the buildings, the stipend of a chaplain, and small allowances to the inmates. An action alleging misappropriation of funds was brought against the corporation in Chancery.

In 1836 the Lord Chancellor ordered the appointment of a body of independent trustees to administer the hospital estates, a move which the corporation opposed until 1848. The almshouses have since that time been administered by trustees under successive schemes of management. A scheme of 1891, still in operation in 1926, provided for the support in the almshouses, with the assistance of a chaplain and a beadle, of thirteen poor of either sex and over 50 years of age who had been reduced by misfortune from better circumstances. The numbers and qualifications were thus similar to those found in the 14th century.

The Chester Infirmary was founded here during the second half of the eighteenth century at a time that saw a new era on many signs of social conscience and philanthropic ventures in its contribution to the poor. The infirmary was founded as a charitable institution for the treatment of the sick poor, largely owing to a bequest of £300 from Dr Stratford in 1753. It was housed in an unoccupied part of the upper floor of the Blue Coat School. At a meeting in June 1755, it was decided that part of the school should be fitted up on a temporary basis until the completion of a fine new building on the other side of the city close to the Roodee (a building that survives to this day, albeit converted into luxury apartments). The infirmary was support by subscriptions and donations. The first patient was one William Thomson of St. Mary's Parish, who was admitted with a wounded hand on November 11th 1755.

The

Bluecoat

School

was

restored and the almshouses rebuilt

in

1854,

at

which

time

various

Roman

roof

tiles

and

bronze

articles

were

found.

The

recently-repainted

figure

of

a

Bluecoat

boy

visible

in

a

niche

on

the

front

of

the

building

(illustrated above) was

also

added

at

this

time.

The

model

for

this

statue

was

one John

Coppack,

who

was

14

years

old

at

the

time.

After

leaving

the

Bluecoat

School,

he

went

to

work

for

the

Shropshire

Union

Canal

Company,

lived

in

Garden

Lane

(just

round

the

corner)-

and

became

the

father

of

14

children! The

Bluecoat

School

was

restored and the almshouses rebuilt

in

1854,

at

which

time

various

Roman

roof

tiles

and

bronze

articles

were

found.

The

recently-repainted

figure

of

a

Bluecoat

boy

visible

in

a

niche

on

the

front

of

the

building

(illustrated above) was

also

added

at

this

time.

The

model

for

this

statue

was

one John

Coppack,

who

was

14

years

old

at

the

time.

After

leaving

the

Bluecoat

School,

he

went

to

work

for

the

Shropshire

Union

Canal

Company,

lived

in

Garden

Lane

(just

round

the

corner)-

and

became

the

father

of

14

children!

The

school

finally

closed

in

1949

and rather fell into decline, as the old photograph on the right shows; missing its railings and with its windows broken. Since

when

the

buildings

have

been

used

for

a

variety

of

purposes,

such

as

retail

and

office

premises,

adult

education

and

a

youth

club.

In

September

1996,

it

became

the

new

home

of

the

history

department

of

the University of Chester.

Various

lecture

rooms

were

created

from

the

former

dormitories

and

headmaster's

study,

the

old

chapel

became

the

reception

area

and

the

former

schoolroom

was

used

by

the

city's

archaeologists. In early 2003, the Bluecoat's basement

was converted to house a new employment and 'enterprise' centre.

In April 2006, a brand new almshouse- the first to be built since the mid-19th century- was opened in the square behind the Bluecoat. Watched by its first tenant, Mary Pritchard, the formal opening of the new one-bedroom self-contained property was carried out by the Lord Mayor and the Chairman of the body that today administers the almshouses, the Chester Municipal Charities.

All of these enterprises eventually moved out and the building sat unused until early 2014, when a radical programme of restoration took place to prepare it to become The Bluecoat Centre for Charities and Voluntary Organisations. Chester Municipal Charities already owned the northern wing but they purchased the rest from the Bluecoat Foundation to prepare a place for such worthy causes as the Citizen's Advice Bureau and Chester Community Action, both of whom had been occupying cramped officed in the once-grand Folliott House, further down Northgate Street. The new Bluecoat Centre will provide a much-need 'one-stop shop' for advice services in the city as well as providing training suites and meeting rooms available for hire to groups not based in the building.

Opposite

the

Bluecoat

formerly

stood

a Bridewell or House

of

Correction where 'petty'

crimes were

punished

by

confinement

and

hard

labour. It seems also to have served as a sort of workhouse; in 1685, Ann Mynshull left in her will "rents for the maintainance of poor freemen's children at work in a house called the House of Correction standinge neare unto the Northgate". Opposite

the

Bluecoat

formerly

stood

a Bridewell or House

of

Correction where 'petty'

crimes were

punished

by

confinement

and

hard

labour. It seems also to have served as a sort of workhouse; in 1685, Ann Mynshull left in her will "rents for the maintainance of poor freemen's children at work in a house called the House of Correction standinge neare unto the Northgate".

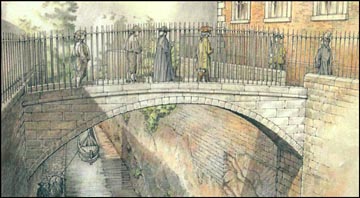

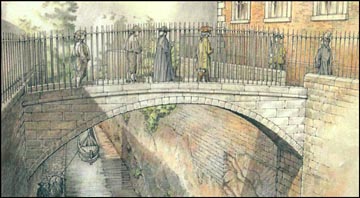

Crossing

the

canal

between

the

Bluecoat

and

the

wall

of

the

former

toll house

outside

the

Northgate,

you

can

see

a

dangerous-looking

stone

footbridge-

illustrated

here-

known

as

the Bridge

of

Sighs. This

was

built

by Joseph

Turner (who

was

also

the

architect

of

the Bridgegate and

the Watergate)

in

July

1793

for

the

sum

of £20

in

order

to

prevent

the

many,

often

successful,

attempts

to

rescue

condemned

prisoners

in

the

Northgate

Gaol

when

they

crossed

the

canal

cutting

to

the

chapel

of

Little

St. John

and

the

'apartment

made

for

prisoners'

to

receive

the

last

rites

of

the

church

before

their

execution.

For

a

while

after

the

cutting

was

made,

these

services

were

held

within

the

gaol

itself,

but

when

the

over-fastidious

chaplain

protested

at

having

to

hold

services

there,

it

was

another factor that brought about the erection

of the

the

bridge.

That

it

would

also

serve

as

a

buttress

to

hold

apart

the

sides

of

the

deep

cutting

doubtless

made

the

money

easier

to

raise.

As may be seen in this artist's impression of the bridge when it was in use, it

was

formerly

equiped

with

iron

railings

on

either

side

to

prevent

suicidal

escape attempts

into

the

deep chasm

below. These, in common with many of those throughout the Kingdom-

including the author's home- were

taken

away to be recycled into munitions

during

both

World

Wars. As may be seen in this artist's impression of the bridge when it was in use, it

was

formerly

equiped

with

iron

railings

on

either

side

to

prevent

suicidal

escape attempts

into

the

deep chasm

below. These, in common with many of those throughout the Kingdom-

including the author's home- were

taken

away to be recycled into munitions

during

both

World

Wars.

Though

the

chapel

and

the

dreadful

prison

are

long

gone,

the

Bridge

of

Sighs

remains-

despite

the

city

authorities

ordering

its

removal

in

1821-

accessible

now

only

to

the

pigeons,

a

source

of

great

fascination

for visitors to

this

day.

The long, low building on the left of our photograph- (and seen again below) to which the bridge attaches but, curiously, allows no access, is today a private residence but once served as a school- reader Charles Jones wrote to tell us that it was run by a Miss Smith and that his mother Dorothy, born in 1919, had studied there. Before that, it served as a toll house from where monies were collected from those entering the town to conduct business and attend the fairs and markets. These tolls, known as murage, were used specifically for the upkeep of the City Walls.

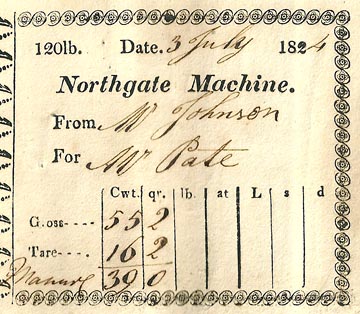

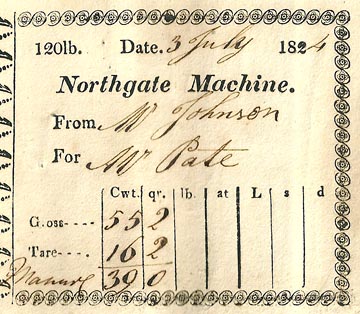

The tale is told that once, a farmer coming in from the countryside with a great load of hay, refused to pay the demanded money and so the toll collector attempted to remove the bridle from his horse in lieu of payment. His rough handling of the beast caused it to rear up and bolt down Northgate Street, shedding the load, scattering people and causing all manner of damage. It is said that the collecting of tolls ceased from this time. On the left we see a rare survivor, one of the tickets issued by the toll collector at the 'Northgate Machine', one Mr Pate, in 1824.

•

We will be further discussing both the murage of the past and recent concern over the present condition of Chester's venerable walls when we shortly reach our North Wall chapter.. •

We will be further discussing both the murage of the past and recent concern over the present condition of Chester's venerable walls when we shortly reach our North Wall chapter..

Standing

upon

the

Northgate, looking

away

from

the

town,

on

our

right

is

a large and

ornate

Victorian

pub,

the Bull

&

Stirrup,

whose

interesting

name

recollects

the

presence

of

the

Cattle

Market

formerly

situated

on

the nearby, curiously-named Gorse

Stacks,

and

also

the

'stirrup

cup' -

or

'one

for

the

road'-

doubtless

frequently

enjoyed

by

the

market's

customers

before

departing

for

their

farms.

Directly opposite

this

is Canal

Street which,

if

followed,

would

take

you

downhill

to

the

Shropshire Union Canal

and

the

fascinating

area

around Tower

Wharf,

which

we

will

be

visiting

later

in

our

stroll.

Looking

ahead,

we

see

at

the

further

end

of

Upper

Northgate

Street

another

large

public

house,

the George

&

Dragon (illustrated below) at

which

point

the

road

divides-

the

right

branch

to

Eastham

and

Liverpool

and

the

left

to

Chester's

ancient

outlying

harbours

at Neston,

Dawpool, Parkgate and Meols on

the Wirral

Peninsula. Meols is of particular antiquity, trading as it did for centuries before the arrival of the Legions. It still exists today as a pleasant residential suburb but the venerable seaport is long lost beneath the waves.

This

road junction

certainly

existed

in

Roman

times-

and

probably

much

earlier-

and,

as

with

the

other

main

routes

leading

to

their

fortress,

the

rough-hewn

memorial

stones

of

a

Roman

cemetery

for centuries occupied

each

side

of

the

road.  Later, the

site

of

the

modern pub

was

occupied

by

a

church

dedicated

to St. Thomas Becket,

shown

on

Daniel

King's

plan

of

Chester

c.1620.

It

was

converted

into

a

private

house

by

Richard

Dutton,

who

was

Mayor

in

1627,

and

was

afterwards

known

as Jolly's

Hall.

In

1645,

during

the

Civil

War,

it

shared

the

fate

of

most

of

the

other

buildings

standing

outside

the

City

Walls,

being

either

burned

by

the

besiegers

or

demolished

by

the

townspeople

themselves

so

as

not

to

afford

shelter

to

Parliamentary

snipers.

It

is

mentioned

by

Randle

Holme

III

in

his

moving description of

the

devastation

inflicted

upon

the

city

at

that

time: Later, the

site

of

the

modern pub

was

occupied

by

a

church

dedicated

to St. Thomas Becket,

shown

on

Daniel

King's

plan

of

Chester

c.1620.

It

was

converted

into

a

private

house

by

Richard

Dutton,

who

was

Mayor

in

1627,

and

was

afterwards

known

as Jolly's

Hall.

In

1645,

during

the

Civil

War,

it

shared

the

fate

of

most

of

the

other

buildings

standing

outside

the

City

Walls,

being

either

burned

by

the

besiegers

or

demolished

by

the

townspeople

themselves

so

as

not

to

afford

shelter

to

Parliamentary

snipers.

It

is

mentioned

by

Randle

Holme

III

in

his

moving description of

the

devastation

inflicted

upon

the

city

at

that

time:

"Without

the

Northgate,

from

the

said

gate

to

the

last

house,

Mr.

Duttons (Jollye's

Hall),

all

burned

and

consumed

to

the

ground,

with

all

the

lanes

to

the

same,

with

the

Chappelle

of

Little

St. John,

not

to

be

found..."

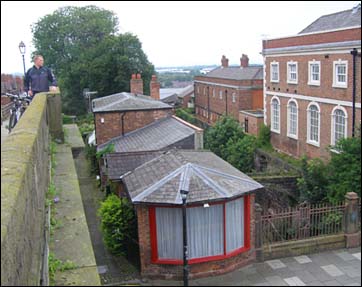

Right: standing atop the Northgate, we see the curious little house where tolls were once collected upon goods entering the city. Behind it, the Bridge of Sighs may jst be seen crossing the deep chasm in which the Shropshire Union Canal flows. On the right may be seen the Bluecoat with its almshouses standing behind. Photographed by the author in 2008.

However,

at

least

part

of

it

must

have

survived,

as

the

1795

Chester

Directory

mentions

the

old

church "being

used

as

a

barn".

Later still,

the

site

was

occupied

by

John

Fletcher's

large

mansion,

"Surmounted

by

a

glass

cupola,

forming

an

excellent

observatory."

Our photograph shows

the

fine, timber and brick-built George

and

Dragon, newly built by the Birkenhead Brewery Company in the 1930s, but it looks much the same today and is well worth examining, being rich with decorative carvings, leaded lights and heavy oak doors.

With

such

a

colourful history,

it

is

not

surprising

that this

is

yet

another

Chester

pub

with

a

reputation

for

being haunted.

The

etherial

occupant

is

known

to

the

staff

as

'George'

(a name shared in common with many of Chester's pub ghosts) and

one

of

them

told

us

he

commonly

made

his

presence

known

at

the

end

of

the

night

when

they

were

cleaning

up- "He

really

hates

the

vacuum

cleaner!"

'George' may actually have been around for quite some time, as legend has it that it is the ghost of a Roman soldier who paces the pub. We may ask why he should eternally revisit this particular spot? Chester was, of course, a fortress town filled once with such men, but the site of the George & Dragon is outside the Porta Decumana, or North Gate and was utilised as a burial ground. As the practical Romans, not wishing to waste space within the fortress, always laid their dead to rest outside the defensive walls, this upper part of Parkgate Road would once have been lined with elaborate memorials to depated citizens and servicemen.

Our particular Roman soldier is said to have fallen in love with a beautiful Welsh girl. While he should have been on sentry duty at the Decumana Gate, he was in the habit of slipping off beyond the walls to meet his love. This young lady was not what she seemed however, and one night, while she kept the sentry occupied, a raiding party led by her brothers gained entry into the garrison, massacring many of its complement of soldiers who were sleeping in their beds. Our particular Roman soldier is said to have fallen in love with a beautiful Welsh girl. While he should have been on sentry duty at the Decumana Gate, he was in the habit of slipping off beyond the walls to meet his love. This young lady was not what she seemed however, and one night, while she kept the sentry occupied, a raiding party led by her brothers gained entry into the garrison, massacring many of its complement of soldiers who were sleeping in their beds.

The hapless soldier would have certainly been executed after such dereliction of duty. For this transgression of the strict Roman code of honour and obedience there would have been no mercy. The unfortunate man perhaps even took his own life out of remorse, and his ghost is now said to pass backwards and forwards through the walls of the George & Dragon, never seen, only heard, forever pacing, to this day. As an honourable burial would not have been afforded him, perhaps the soldier seeks his rest at the site of the former cemetery. Could he be seeking his murdered comrades to ask their forgiveness? Whatever the reason for his wanderings, he remains "the lost legionary".

(Until the 1960s, across town on the corner of Frodsham Street and Foregate Street stood for centuries the Bear's Paw Inn. Today, the site is occupied by a utilitarian structure which houses a branch of H. Samuels jewellers. Conversing with the staff recently, we were fascinated to discover that they were all familiar with a ghost of their own- also familiarly known as George, doubtless a long-standing habituee of the long-vanished pub, who just didn't want to go home at closing time!)

Of the

inns

of

Northgate

Street

it was once said that "they are as common as blackberries". We will be visiting some of them in

our next

chapter and here is a list of the many, many other Chester pubs that have sadly ceased to be over the years...

Of

more

recent

times,

the

view

beyond

the

Northgate

has

been

considerably

altered

by

the

construction

of

the Fountains

Roundabout as

part

of

the

1960s Inner

Ring Road scheme.

This

was

described

by

the

press

at

the

time

of

its

opening

in

1967

as "Chester's

most

notable

non-place"-

it

was

laid out

with

attractive lawns,

flowerbeds

and

fountains,

but

allowed

no

safe

pedestrian

access.

The eminent architectural critic Nikolas Pesvenor

commented,

"The

roundabout

with

its

well-intentioned

fountain

destroys

the

street

continuity,

and

indeed

the

town

scale". Of

more

recent

times,

the

view

beyond

the

Northgate

has

been

considerably

altered

by

the

construction

of

the Fountains

Roundabout as

part

of

the

1960s Inner

Ring Road scheme.

This

was

described

by

the

press

at

the

time

of

its

opening

in

1967

as "Chester's

most

notable

non-place"-

it

was

laid out

with

attractive lawns,

flowerbeds

and

fountains,

but

allowed

no

safe

pedestrian

access.

The eminent architectural critic Nikolas Pesvenor

commented,

"The

roundabout

with

its

well-intentioned

fountain

destroys

the

street

continuity,

and

indeed

the

town

scale".

Even

worse,

to

cross

the

busy

Ring Road,

one

is

forced

to

burrow

under

it

via

a

series

of

unpleasant

subways.

Many

local

people

felt

that,

after

thirty

years,

this

sorry

piece

of

town

planning

was

long

overdue

for

improvement

and, in fact,

a

couple

of

these

subways

have

already

been

filled

in

and

replaced

with

Pelican

crossings.

We often hear it said by Chester's current crop of planners and politicians that follies of this sort are a thing of the past, that lessons have been learned and that much more care is now taken when considering the nature of new architecture in our ancient and beautiful city. That said, let us finally draw your attention to this brand new addition to the landscape of Upper Northgate Street- a 160-bed Travelodge hotel, a vast, ugly and deeply inappropriate structure that, since emerging from its scaffolding in the Summer of 2011 has been soundly panned by Chester's shocked residents and visitors, few of whom (planners and politicians aside) had entertained the slightest suspicion that such a monstrosity was to be foisted upon their fair city, not a mention of it having been made in the local press or elsewhere. And who can blame them. What a ghastly blot.

The architects, Manchester-based Stephenson-Bell, wrote of their brief (for client Rufus Estates) on their website- make of it what you will- "The site is an important ‘gateway’ to the northern entrance to the historic city, which demands a powerful design that is simultaneously sensitive to the historic neighbours. A limited material palette of black brick, render and glass is proposed as a modern interpretation of the ‘wattle and daub’ facades that typify many of Chester’s historic buildings". The architects, Manchester-based Stephenson-Bell, wrote of their brief (for client Rufus Estates) on their website- make of it what you will- "The site is an important ‘gateway’ to the northern entrance to the historic city, which demands a powerful design that is simultaneously sensitive to the historic neighbours. A limited material palette of black brick, render and glass is proposed as a modern interpretation of the ‘wattle and daub’ facades that typify many of Chester’s historic buildings".

You couldn't make it up.

Consider the words of the statesman, Prime Minister and local lad William Ewart Gladstone (1809-1898)- who was born in Liverpool and lived in Hawarden- "The manufacturer [and architect] whose daily thought is to cheapen his productions, endeavouring to dispense with all that can be spared, is under much temptation to decline letting beauty stand as an item in the account of the costs of production. So the pressure of economical law tells severely upon the finer elements of trade. And yet it may be argued that, in the case of the durability and solidity of articles, that which appears cheapest at first may not be cheapest in the long run… there seems to be a way by which the law of nature arrives at its revenge upon the short-sighted lust for cheapness. We begin, say, by finding beauty expensive. We decline to pay the artists for producing it. Their employment ceases; and they disappear. Presently we find that works reduced to utter baldness do not satisfy. We have to meet a demand for embellishment of some kind. But we have starved out the race who knew the laws and modes of its production. We substitute strength for flavour, quantity for quality; and we end by producing incongruous excrescences, or even hideous malformations, at a greater cost than would have sufficed for the nourishment among us of chaste and virgin art".

And also of Canadian architect and urban planner Arthur Erickson: "Today's developer is a poor substitute for the committed entrepreneur of the last century for whom the work of architecture represented a chance to celebrate the worth of his enterprise".

Within a mere two years, the hotel was deemed a failure and the building was taken over by Chester University to serve as a student hall of residence, which contains 160 en-suite rooms and opened in late September 2013. It has been re-named Sumner Hall after Bishop of Chester John Sumner, one of the University's founders in 1839, 174 years ago. From 1848 until his death in 1862, he served as Archbishop of Canterbury.

None of which makes the place anything less of a carbuncle. Ironically, in October 2013, a proposed student housing development just across the roundabout, on the site of a vile 1960s building next door to the Northgate Church, was refused on the grounds that it was too large..

But now

we'll

move

on

to

the

final

part

of

our

exploration

of

the

Northgate

Street

area: Inns

and

Brewers ...

Curiosities

from

Chester's

History

no. 2

|

rominent

in

Chester's

Market

Square, and

seen here in a photograph taken on a snowy day in 1917,

is the Town

Hall,

which

was

built

in

1864-9

in

an interpretation of the

Gothic

style

of

the

late

13th

century

by William

Henry

Lynn (1829-1915) of

Belfast,

to

replace

the

17th

century Exchange which

stood

in

the

middle

of

the

square

before

burning

down

in

1862.

rominent

in

Chester's

Market

Square, and

seen here in a photograph taken on a snowy day in 1917,

is the Town

Hall,

which

was

built

in

1864-9

in

an interpretation of the

Gothic

style

of

the

late

13th

century

by William

Henry

Lynn (1829-1915) of

Belfast,

to

replace

the

17th

century Exchange which

stood

in

the

middle

of

the

square

before

burning

down

in

1862. Preparations for the royal visit were discussed at great length by the Corporation and, aware that the nation's eyes would be upon them, it was agreed that no cost was to be spared to make the event a success. Roads were dug up to lay gas pipes to provide the necessary extra illumination- the Prince was due to arrive as dusk fell- and three large viewing galleries with room for 2,500 spectators were erected in the Market Square. To preserve public order, an additional 500 police and 22 detectives were hired and fireworks for a grand display at the Roodee, Chester's ancient racecourse, were ordered. Houses and shops throughout the city were repainted and the Eastgate railings were painted bright blue tipped with gold.

Preparations for the royal visit were discussed at great length by the Corporation and, aware that the nation's eyes would be upon them, it was agreed that no cost was to be spared to make the event a success. Roads were dug up to lay gas pipes to provide the necessary extra illumination- the Prince was due to arrive as dusk fell- and three large viewing galleries with room for 2,500 spectators were erected in the Market Square. To preserve public order, an additional 500 police and 22 detectives were hired and fireworks for a grand display at the Roodee, Chester's ancient racecourse, were ordered. Houses and shops throughout the city were repainted and the Eastgate railings were painted bright blue tipped with gold.  The following day, the Cheshire Observer observed that "the city may now lay aside its toys, take down the bunting, remove the barriers and arches and once more return to its ordinary, everyday life".

The following day, the Cheshire Observer observed that "the city may now lay aside its toys, take down the bunting, remove the barriers and arches and once more return to its ordinary, everyday life".

The cost of building the Town Hall somewhat overran the original budget of £16,000- eventually costing almost £50,000- around two and a half million pounds in today's money.

The cost of building the Town Hall somewhat overran the original budget of £16,000- eventually costing almost £50,000- around two and a half million pounds in today's money. The City Council meet in a grand chamber on the first floor which had to be rebuilt by the prolific local architect

The City Council meet in a grand chamber on the first floor which had to be rebuilt by the prolific local architect  A major programme of restoration was embarked upon in early Summer 2008 and, for many months, the exterior was shrouded in a great mass of scaffolding. The stonework was cleaned and pointed and guttering and roofs repaired, and, now the scaffolding has been removed, this handsome building is looking better than it has done in years.

A major programme of restoration was embarked upon in early Summer 2008 and, for many months, the exterior was shrouded in a great mass of scaffolding. The stonework was cleaned and pointed and guttering and roofs repaired, and, now the scaffolding has been removed, this handsome building is looking better than it has done in years.

Eventually, in September 2011, the building was finally re-acquired by the local authority and soon after it was announced that it will indeed become the home of Chester's new theatre. Whether there will also be room for a cinema as well is currently unknown.

Eventually, in September 2011, the building was finally re-acquired by the local authority and soon after it was announced that it will indeed become the home of Chester's new theatre. Whether there will also be room for a cinema as well is currently unknown. Across Northgate Street from the Odeon, the ground floors of the buildings between the Little Abbey Gateway (see below) and the Northgate are all converted into shops but, looking up (which few people do), it is evident that the southern range were once gracious Georgian mansions housing affluent families. The spout head on the one nearest to the gateway bears the date 1749. Another, nearer to the gate- and the location of the author's studio and gallery,

Across Northgate Street from the Odeon, the ground floors of the buildings between the Little Abbey Gateway (see below) and the Northgate are all converted into shops but, looking up (which few people do), it is evident that the southern range were once gracious Georgian mansions housing affluent families. The spout head on the one nearest to the gateway bears the date 1749. Another, nearer to the gate- and the location of the author's studio and gallery,  Information

about

the

so-called Northgate

Development

Proposals and their sponsors ING having

grown

considerably,

we

have

now

given

them

their

own

Information

about

the

so-called Northgate

Development

Proposals and their sponsors ING having

grown

considerably,

we

have

now

given

them

their

own

Back

atop

the

Northgate

and

standing

with

our

backs

to

the

city,

across

the

spectacular

canal

cutting

we

see

on

our

left

the Bluecoat

School,

the

first

charity

school

built

outside

London

by

the Society

for

the

Promotion

of

Christian

Knowledge.(The

SPCK

still

exists

today

of

course,

and

until recently maintained

a

bookshop

in

nearby

St. Werburgh

Street).

Back

atop

the

Northgate

and

standing

with

our

backs

to

the

city,

across

the

spectacular

canal

cutting

we

see

on

our

left

the Bluecoat

School,

the

first

charity

school

built

outside

London

by

the Society

for

the

Promotion

of

Christian

Knowledge.(The

SPCK

still

exists

today

of

course,

and

until recently maintained

a

bookshop

in

nearby

St. Werburgh

Street). The extensive privileges given to the hospital by Ranulph III were a potential cause of conflict and early in its history arrangements were made to protect the interests of the existing churches in Chester. It was agreed between the brethren of the hospital and the Abbot of

The extensive privileges given to the hospital by Ranulph III were a potential cause of conflict and early in its history arrangements were made to protect the interests of the existing churches in Chester. It was agreed between the brethren of the hospital and the Abbot of  The hospital was to take in as many poor and sick as possible but thirteen beds were to be kept ready for the

housing

of

"thirteen