|

oregate

and Eastgate Streets lay on the line of Watling Street, the

Saxon name for the great Roman road which commenced at Dover, passed through

London and crossed the country to enter the fortress of Deva at the now-vanished

South Gate and leave by the Eastgate, the Porta Principalis Sinistra,

on its way to Manchester and York. oregate

and Eastgate Streets lay on the line of Watling Street, the

Saxon name for the great Roman road which commenced at Dover, passed through

London and crossed the country to enter the fortress of Deva at the now-vanished

South Gate and leave by the Eastgate, the Porta Principalis Sinistra,

on its way to Manchester and York.

(Of particular interest to students of Chester is a chapter in Thomas Codrington's

1903 Roman Roads in Britain dealing with ancient Watling Street,

which you may read here)

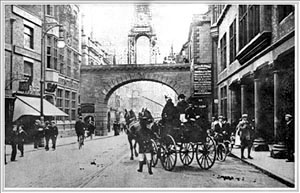

Right: an evocative view of the City Wall and Eastgate Clock in the 1920s

Eastgate

Street

and

its

continuation

beyond

the Cross, Watergate

Street,

lie

approximately

on

the

line

of

the

main

thoroughfare

of

Roman

Deva,

the Via

Principalis (Chester,

incidentally,

is

the

only

city

in

Britain

where

the

main

streets

are

signposted

in

both

English

and

Latin).

From

where

we

stand,

the

street

extends

220

yards

to

the

Cross

and

the

square

tower

of St. Peter's

Chuch,

the

site

of

the

southern

side

of

the

great Principia,

or

Roman

headquarters

building

and

on

again

the

same

distance-

the

tall

spire

of Holy

Trinity

Church in

Watergate

Street

marks

the

site

of

the

vanished

West

Gate,

or Porta

Principalis

Dextra.

This

shows

at

a

glance

the

extent

of

the

fortress

across

its

narrower

side-

about

440

Could

the

Saxon

founders

of

Holy

Trinity

have

utilised

a

ruined

Roman

gatehouse

adjoining

the

West

Gate

of

the

fortress?

A

very

similar

situation

existed

in

what

is

now

the

middle

of

the

busy

junction

of

Bridge

Street

and Grosvenor

Street,

where

for

centuries

there

stood

a

church

dedicated

to

St. Bridget,

which

was

founded

around

the

year

797

by

King

Offa

on

the

site

of

the

vanished

Roman

South

Gate, or Porta

Praetoria.

Some

mighty

column

bases

from

the

vanished Principia were

discovered

when

the

old Shoemaker's

Row in

Northgate

Street

was

rebuilt

and

have

been

preserved.

You

can

inspect

them

(well

worth

the

effort)-

albeit

through

an

inappropriate

mass

of

merchandise,

in

the

basement

of

what

was

until

recently

a

clothes

shop.

From the Cross, the ancient meeting place of the principal streets of Chester,

a right turn will take you back to our starting place, the Northgate,

a left takes you down Bridge Street to the River Dee and the Bridgegate while continuing strait on into Watergate Street will eventually bring us

to the Watergate. On either side, you

can see the openings of the remarkable covered galleries known as The Rows,

an architectural feature unique to Chester. There are numerous theories as to their  origins, for example, that they

evolved from the structures that came to be erected, one row above another,

on the sloping piles of rubble that lined the main streets in the centuries

following the departure of the Legions and the destruction of the buildings

within their great fortress. Go here to read Joseph Hemingway's lengthy description of the Rows, written 170 years ago, in 1836 but still entirely recognisable today. origins, for example, that they

evolved from the structures that came to be erected, one row above another,

on the sloping piles of rubble that lined the main streets in the centuries

following the departure of the Legions and the destruction of the buildings

within their great fortress. Go here to read Joseph Hemingway's lengthy description of the Rows, written 170 years ago, in 1836 but still entirely recognisable today.

Left: Eastgate Street. When the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII, visited Chester in 1869 to open the Town Hall, he exclaimed as he seated himself in the Mayor's open carriage, and looked at this view towards the High Cross from the Grosvenor Hotel, " What a glorious picture! "What a beautiful skyline!"

"Chester is a town of balconies. The first impression I received

of it was a town whose inhabitants spend a great portion of their lives

leaning over old oak galleries, smoking and chatting and watching life go

by below them in the streets.

The Rows are simply long, covered arcades formed by running a highway through

the first stories of a street of old buildings. You mount from the roadway

to the Rows on frequent flights of stone steps and find yourself in the

strangest shopping streets in England. Here are the best shops hidden away

in the darkness of these ancient arcades, and it is possible to shop dry-shod

in the worst weather.

There is a peculiar charm about these Rows. They are not typically medieval,

because there is no record of any other street of this kind in the Middle

Ages, yet they impart a singular impression of medievalism: through the

oak beams which support the galleries you see black-and-white half-timbered

houses on the opposite side of the street, with another Row cut through

their first floors, on whose balconies people are leaning and talking and

regarding the flow of life.

The main streets of Chester give you the impression that a huge galleon

has come to anchor there with easy, leisurely passengers leaning on the

deck rails"

H. V. Morton: In Search of England 1924

You

can

read

more

of

Mr Morton's

impressions

of

Chester here. You

can

read

more

of

Mr Morton's

impressions

of

Chester here.

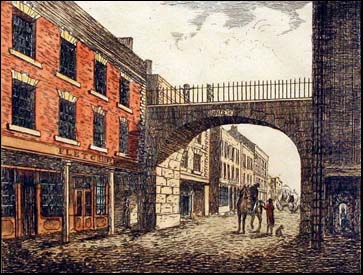

The

Eastgate

The

present

Eastgate

was

designed by one Mr Hayden and erected

in

1769 at the expense of Richard, Lord Grosvenor. It comprises a

plain

stone

archway

with

small

posterns

on

either

side

for

pedestrian

access.

On

the

outside

of

the

gate

are

the

arms

of

the

Grosvenors

and

the

inscription:

"ERECTED

AT

THE

EXPENCE

OF

RICHARD

LORD

GROSVENOR

A:D:

MDCCLXIX"

On

the

west

side

are

displayed

the

city

arms

and,

"THIS

GATE

BEGUN

A.D.

MDCCLXVIII

JOHN

KELSALL

ESQr.

MAYOR.

FINISHED

A.D.

MDCCLXIX

CHA.

BOSWELL

ESQr.

MAYOR"

It

replaced

a

great

medieval

structure

formerly

occupying

the

site, "A

goodly

great

gate,

of

an

antient

fair

building,

with

a

tower

upon

it,

containing

many

fair

rooms

within".

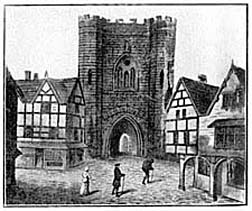

This

old

Eastgate

was

a

massive

affair of high quality masonry of a cream-coloured sandstone,

which must have contrasted strikingly with the red stone which was the norm in the city. It comprised

a

single

pointed

arch

supporting

a

great

high

square

battlement

of

stone

with

octagonal

corner

turrets,

arrowslits

and

crenellations.

There were small flanking towers. The

tower

above

it

was

known

as

the Harre (Harry) Tower. This

old

Eastgate

was

a

massive

affair of high quality masonry of a cream-coloured sandstone,

which must have contrasted strikingly with the red stone which was the norm in the city. It comprised

a

single

pointed

arch

supporting

a

great

high

square

battlement

of

stone

with

octagonal

corner

turrets,

arrowslits

and

crenellations.

There were small flanking towers. The

tower

above

it

was

known

as

the Harre (Harry) Tower.

In 1586, the Harre Tower was let to the Joiner's Company at a yearly rental of 6s. 8d.

We are unsure as to when exactly this great structure was erected but it does bear striking similarities to Caernarfon Castle and it is recorded that, in 1270, Henry III acquired land at the East Gate from one Agnes de Novo Castello (New Castle) which was confirmed in a writ of 1307. So a construction date sometime in the early 14th century seems likely.

This

medieval

gate

in

turn

replaced

the

original

Roman

entrance,

while

incorporating

much

of

that

structure

within

it.

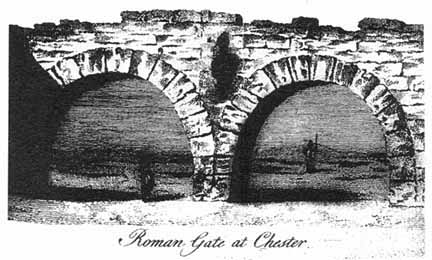

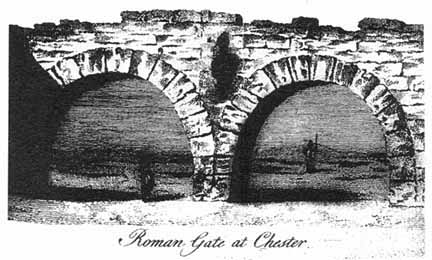

Drawings

exist

recording

the

demolition

of

the

medieval

gate,

clearly

showing

the

twin

barrel-vaulted

arches

of

the

Roman

entrance,

14

feet

high

and

20

feet

apart,

complete

with

guard

houses

on

each

side.

Mounted

between

the

arches

was

a

sculpted

image

of

a

centurion,

or

perhaps

of

Mars,

the

Roman

god

of

war,

arrayed

in

armour

and

holding

a

shield

in

one

hand

and

a

spear

in

the

other.

Whoever

it

actually

represented,

this

image

must

have

been

a

welcome

sight

to

generations

of

tired

Roman

infantrymen

approaching

the

end

of

a

long

march.

Distinguished

18th

century

travel

writer

and

naturalist Thomas

Pennant,

alluding

to

the

old

gate,

wrote "I

remember

the

demolition

of

the

ancient

structure,

and

on

taking

down

the

more

modern

case

of

Norman

masonry

the

Roman

appeared,

full

in

view.

It

consisted

of

two

arches,

formed

of

vast

stones,

fronting

the

Eastgate

Street

and

Forest

Street -

the

pillar

between

them

dividing

the

street

exactly

in

two".

(The name of Forest Street, incidentally- now Foregate Street- had, as is commonly claimed, nothing to do with it being the road to the forests that once thrived beyond the city but was a corruption of 'Fore-East Street'- the street before the Eastgate.) (The name of Forest Street, incidentally- now Foregate Street- had, as is commonly claimed, nothing to do with it being the road to the forests that once thrived beyond the city but was a corruption of 'Fore-East Street'- the street before the Eastgate.)

In

1910,

Chester

historian Frank

Simpson commented "What

a

pity

it

was

ever

to

have

removed

the

ancient

Eastgate

at

all.

What

a

beautiful

relic

of

Norman

times

would

have

now

remained

if

the

road

had

been

diverted

on

either

side

of

it!"

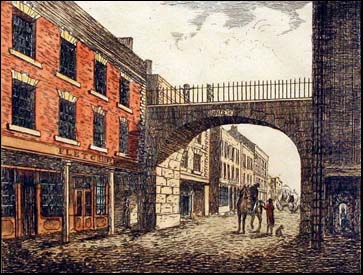

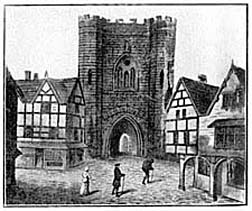

Right: the Eastgate as it appeared in 1820, viewed from outside the City Walls.

Writing in 1858, the excellent Thomas Hughes expressed it rather more strongly: "Handsome and commodious as is the present Eastgate- on every score but that of convenience, it is immeasurably inferior to its predecessor. Could we but look upon the structure as it existed only a hundred years ago, with its beautiful Gothic archway, flanked by two massive octagonal towers, four stories in height, supporting the gate itself and the rooms above- could we but resuscitate the time-worn battlements of that "ancient of days", we should wonder at and pity the spurious taste that decreed its fall. "Oh but", we may be told, "the present gate is a public improvement". A plague upon such improvements, say we! We would vastly have preferred, and so would every lover of the antique, whether citizen or stranger, to have retained the old gate in its integrity, altered, had need been, to meet the growing wants of the times, rather than have thus consigned it to the ruthless hands of the destroyer. Oh! Ye spirits of the valiant dead- you who lost your lives defending this gate against Cromwell, why did ye not rise up from your graves and arrest the mad course of that "age of improvement?"

Tragically,

that

which

had

miraculously

survived

for

around

sixteen

hundred

years

was

thoughtlessly

done

away

with

in

a

matter

of

days.

All

that

now

survives

is

a

section

of

wall

which

probably

belonged

to

one

of

the

guard

chambers

preserved

in

the

cellar

of

no. 48

Eastgate

Street.

The 'Honorable

Incorporation'

As

you

look

at

the

Eastgate

from

within

the

wall,

on

the

left-hand

side,

immediately

next

to

the

gate

is

a

narrow

passageway.

At

the

end

of

this,

in

what

is

now

the

premises

of

a

bank,

formerly

existed

a

public

house

called

The King's

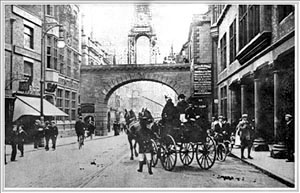

Arms

Kitchen, also known as Mother Hall's.

You

may

just

see

its

sign

on

the

left

of

the

Eastgate

in

the

photograph

below,

which

was

taken

about

1900.

In

the

18th

and

19th

centuries,

it

housed

a

society

going

by

the

splendid

name

of The

Honorable

Incorporation

of

the

King's

Arm's

Kitchen.

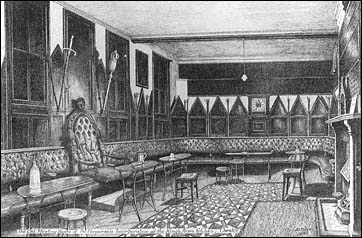

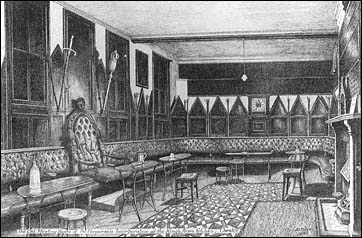

This came about as the result of an order by King Charles II that the custom of electing the mayor and his officers was to end. Sir Thomas Grosvenor was appointed as mayor, thus spawning an oligarchy between Eaton Hall (the Grosvenor residence) and Chester Corporation that would last until the Election Reform Act of 1832. The city's people were, unsurprisingy, increasingly unhappy with this imposition of an unelected mayor and Corporation, and one evening around the year 1770, a group of tradesmen met in a room in this pub and decided to form a City Assembly of their own, which

was

organised

(a wonderful idea) as

a

complete shadow assembly, a satirical

imitation

of

the

Corporation,

with

its

own

elected

mayor,

recorder,

town

clerk,

sheriffs, aldermen and common councilmen. They even had a replica of the mayor's sword and mace made for them. Their meeting room was fitted with beautiful, diamond shaped oak panels (said to have been fashioned from old pew doors from St John’s Church), plush seating and a grand mayoral throne. On either side of the fireplace were cupboards for the storing of 'churchwardens'- long clay pipes which each member marked with his own monogram. An oil painting of the Royal Arms- the Lion & the Unicorn- was presented by Mr Clowes, a heraldic painter and inscribed “This picture is the property of the Incorporated Society of the King’s Arms Kitchen”. In

the

18th

and

19th

centuries,

it

housed

a

society

going

by

the

splendid

name

of The

Honorable

Incorporation

of

the

King's

Arm's

Kitchen.

This came about as the result of an order by King Charles II that the custom of electing the mayor and his officers was to end. Sir Thomas Grosvenor was appointed as mayor, thus spawning an oligarchy between Eaton Hall (the Grosvenor residence) and Chester Corporation that would last until the Election Reform Act of 1832. The city's people were, unsurprisingy, increasingly unhappy with this imposition of an unelected mayor and Corporation, and one evening around the year 1770, a group of tradesmen met in a room in this pub and decided to form a City Assembly of their own, which

was

organised

(a wonderful idea) as

a

complete shadow assembly, a satirical

imitation

of

the

Corporation,

with

its

own

elected

mayor,

recorder,

town

clerk,

sheriffs, aldermen and common councilmen. They even had a replica of the mayor's sword and mace made for them. Their meeting room was fitted with beautiful, diamond shaped oak panels (said to have been fashioned from old pew doors from St John’s Church), plush seating and a grand mayoral throne. On either side of the fireplace were cupboards for the storing of 'churchwardens'- long clay pipes which each member marked with his own monogram. An oil painting of the Royal Arms- the Lion & the Unicorn- was presented by Mr Clowes, a heraldic painter and inscribed “This picture is the property of the Incorporated Society of the King’s Arms Kitchen”.

In the course of time, the serious, satirical point of the King's Arms Kitchen was largely lost and it degenerated into a drinking and gambling club. The regulars, however, did not forget the old rules and regulations, such as that which declared that if a stranger sat in the mayor's chair, it was his duty to buy drinks for all present. During the Second World War, many an American GI was invited to sit in the mayor's chair!

The

fittings

of

the

room

(illustrated above) where

this

worthy

institution

met,

complete

with

wood

panelling

upon

which

was

inscribed

the

succession

of

member's

names,

was

preserved

when

the

pub

closed

in

1978,

and

was

transferred

to

the Grosvenor

Museum,

where

they

were

imaginitively

incorporated

into

the

decor

of

the

museum's

teashop,

and

may

still

be

seen

there

today.

Go here to

find

out

much more,

and

read

the

fascinating

reminiscences

of

an

anonymous

19th

century

'frequenter'...

On

the

right

of

the

Eastgate

in

this

old

photograph

you

can

see

Huxley's

Vaults,

a

public

house

and

wine

merchant

established

here

in

1783

and

surviving

until

the

1960s.

For unknown reasons (possibly fortunately) Huxley's was also fondly known by its habituees as Dirty Dick's. It was later owned by the Northgate Brewery and only had a six-day licence, being closed on Sundays. The brewery had converted the upper parts of the pub for living accomodation before the war and this then bore the distinguished address of 'Number 11, City Walls'. After the sad demise of the pub, the Leeds Building Society, and later the Halifax, took over the premises and later it housed a moble phone shop but today it is occupied by Milton's jewellers and pawnbrokers. There is a mystery about the Grade II listed building- if you stand outside the Grosvenor Hotel and look up you can see a brass porthole in the side wall. Legend had it that an old sea captain had it put in many years earlier to remind him of his days at sea... On

the

right

of

the

Eastgate

in

this

old

photograph

you

can

see

Huxley's

Vaults,

a

public

house

and

wine

merchant

established

here

in

1783

and

surviving

until

the

1960s.

For unknown reasons (possibly fortunately) Huxley's was also fondly known by its habituees as Dirty Dick's. It was later owned by the Northgate Brewery and only had a six-day licence, being closed on Sundays. The brewery had converted the upper parts of the pub for living accomodation before the war and this then bore the distinguished address of 'Number 11, City Walls'. After the sad demise of the pub, the Leeds Building Society, and later the Halifax, took over the premises and later it housed a moble phone shop but today it is occupied by Milton's jewellers and pawnbrokers. There is a mystery about the Grade II listed building- if you stand outside the Grosvenor Hotel and look up you can see a brass porthole in the side wall. Legend had it that an old sea captain had it put in many years earlier to remind him of his days at sea...

(For much more about the

vanished watering holes of Chester go here.)

The

coach

is

pulling

away

from

the Chester Grosvenor

Hotel,

the

site

of

which

was

originally

occupied

by The Golden Talbot, advertised in the long-defunct Adam's Weekly Courant of 17th September 1751 as "that ancient and well-accustomed inn which is now fitted up in the neatest manner and held by Thomas Hickman (late agent to the Hon. Colonel Lee deceas'd) where all gentlemen, ladies and others who shall be pleased to make use of the said house may depend on the best accomodations and most civil usage".

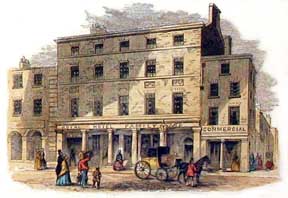

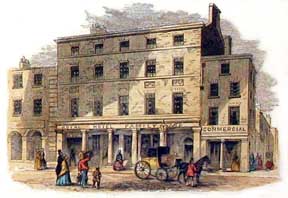

The old Talbot was demolished and on its site rose The Royal

Hotel (illustrated right)

which

was

built

in

1784

by

one

John

Crewe,

who,

together

with

a

Mr Barnston

stood

for

Parliament

as

Whigs

against

Mr Thomas

Grosvenor

and

Mr

Richard

Wilbraham

Bootle

who,

as

Tories,

supported

William

Pitt.

The

two

seats

had

been

Grosvenor

family

'perks'

for

decades,

and

the

city

council

were

hand-in-glove

with

them. The old Talbot was demolished and on its site rose The Royal

Hotel (illustrated right)

which

was

built

in

1784

by

one

John

Crewe,

who,

together

with

a

Mr Barnston

stood

for

Parliament

as

Whigs

against

Mr Thomas

Grosvenor

and

Mr

Richard

Wilbraham

Bootle

who,

as

Tories,

supported

William

Pitt.

The

two

seats

had

been

Grosvenor

family

'perks'

for

decades,

and

the

city

council

were

hand-in-glove

with

them.

After

ten

days

of

campaigning,

the

parties

were

neck-and-neck,

until

money

won

the

day-

Mr

Crewe,

described

as

being

of

'only

moderate

fortune,'

spent

£10,000

on

bribes,

but

the

Grosvenors

spent

£20,000

and

the

Tories

were

in.

(However,

eight

years

later,

the Chester

Directory for

1792

shows

John

Crewe

and

Sir

Robert

Salisbury

Cotton

as

representatives

for

the

county,

while

Thomas

Grosvenor

Esq.

and

the

Right

Hon.

Lord

Belgrave

as

members

for

the

city)

The

antagonism

between

the

Grosvenors

and

city

fathers

on

one

hand

and

their

opponents

on

the

other

went

on

for

a

further

30

years,

but,

despite

rulings

against

them

in

the

House

of

Lords,

the

Tory

stranglehold

over

the

city's

affairs

continued

until

the

reform

act

of

1832.

The Royal

Hotel was

the

opposition's

social

centre,

with

news

and

coffee

rooms

and

an

elegant

assembly

room

for

balls

and

concerts.

Earl

Grosvenor,

however,

had

the

last

laugh.

He

bought

the

building

and

in

1863,

had

it

totally

demolished,

and

replaced

by

the

much

larger

building

we

see

today-

and

named

it

after

his

family. The Royal

Hotel was

the

opposition's

social

centre,

with

news

and

coffee

rooms

and

an

elegant

assembly

room

for

balls

and

concerts.

Earl

Grosvenor,

however,

had

the

last

laugh.

He

bought

the

building

and

in

1863,

had

it

totally

demolished,

and

replaced

by

the

much

larger

building

we

see

today-

and

named

it

after

his

family.

A

century

later,

the

Grosvenor

Hotel

was

considered

a

cosy

and

unpretentious,

if

rather

dowdy

place,

but

it

contained

the

city's

only

large

ballroom

apart

from

that

in

the

Town

Hall,

so

perforce

all

the

balls

(Hunt,

Farmer's,

Conservative and League

of

Pity amongst

them)

were

held

there.

With

the

increasing

prosperity

of

the

city,

the

hotel

underwent

a

programme

of

upgrading

and

refurbishment,

adding

many

modern

conveniences

but

losing

much

of

its

old-world

charm.

Author, broadcaster and all-round character Gyles Brandreth, who served as Chester's

Member of Parliament from 1991-97, referred to the Grosvenor in his wonderfully readable volume of diaries, Breaking the Code thus, "owned by the Duke of Westminster who, I imagine, is about the only person who can actually afford to stay there: it's very lush and very pricey".

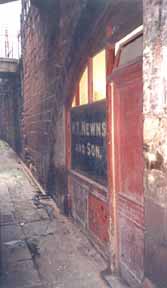

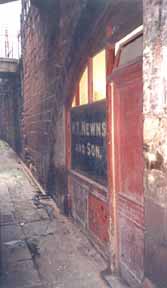

Far humbler perhaps, but no less interesting, is a business premises situated just across the road from the Grosvenor Hotel. Following a sign to the city walls immediately next to the Eastgate leads the visitor to a flight of steps, tucked beneath which is the smallest shop in Chester- possibly in the entire country. Formerly the premises of a wool trader, around the year 1895 it became a gentlemen's hairdressers (three customers and the place was packed!)- and stayed that way for 108 years, until November 2003 when its last owner, long-serving traditional barber Bernie Philips retired. A busy sandwich bar now trades from there. Our photograph shows the still-unaltered rear of the premises.

So, having

re-mounted these steps to the city walls and lingered

awhile

to

watch

the

bustling

crowds

beneath,

we

shall

now

press

on

towards

the Newgate...

Curiosities from Chester's History no. 11

1509 Henry VII died, his second son ascended the throne

as Henry VIII (1491-1547) and married Catherine of Aragon, the widow of his elder brother Arthur. Arthur was the eldest son of Henry and Elizabeth of York. He was born on 20 September 1486, barely a year after the pivotal Battle of Bosworth Field, and died on 2 April 1502. Arthur was named after the mythical King Arthur- Henry VII was Welsh and the legend was popular in medieval England. He was titled Prince of Wales when he was 3 years old. Negotiations for his marriage to Katharine of Aragon, daughter of the famous Ferdinand and Isabella, began in 1488. The terms were settled in 1500 and the couple were married in London on 14 November 1501. They journeyed to Ludlow Castle, the traditional seat of the Prince of Wales, and established a small court. However, Arthur died suddenly on 2 April 1502, possibly of tuberculosis. William

ap John was fined three-halfpence for being a "peeping Tom" 1509 Henry VII died, his second son ascended the throne

as Henry VIII (1491-1547) and married Catherine of Aragon, the widow of his elder brother Arthur. Arthur was the eldest son of Henry and Elizabeth of York. He was born on 20 September 1486, barely a year after the pivotal Battle of Bosworth Field, and died on 2 April 1502. Arthur was named after the mythical King Arthur- Henry VII was Welsh and the legend was popular in medieval England. He was titled Prince of Wales when he was 3 years old. Negotiations for his marriage to Katharine of Aragon, daughter of the famous Ferdinand and Isabella, began in 1488. The terms were settled in 1500 and the couple were married in London on 14 November 1501. They journeyed to Ludlow Castle, the traditional seat of the Prince of Wales, and established a small court. However, Arthur died suddenly on 2 April 1502, possibly of tuberculosis. William

ap John was fined three-halfpence for being a "peeping Tom"

- 1510 An order is made that "none shall attend priest's

offerings, first mass, gospel ales or Welsh weddings, within this city,

under a penalty of ten shillings".

- 1515 A fight took place "betwixte the citizens of Chester

and divers Waylshe men at Saint Warburghe Lane ende but lytill hurt done,

for the Waylesmen fledde".

- 1517 Great visitation of Bubonic Plague; grass grew a

foot high at the High Cross and other streets in the city. Many, it was

said, died "whilst opening their windows." A silence descended upon the

city, relieved only by the cry of the watchmen calling "bring out your

dead" as they went their rounds with the Dead Carts. Before the plague

bore down upon the city, many citzens claimed they witnessed a fiery halo

of light in the heavens above.

- 1519 Hernán Cortéz enters Tenochtitlan,

capital of Mexico, and is received by Montezuma II, the Aztec ruler. Coffee

comes to Europe for the first time.

- 1523 Roger Ledsham, keeper of the Great Gate of the Abbey of St.Werburgh

was drowned in the 'horse-pole' (a pond formerly situated in present-day

Abbey Square)

- 1524 Turkeys from South America first eaten

at the English court. Thomas Highfield becomes twenty fifth

Abbot of St. Werburgh's (-1527)

- 1526 The Abbey cloisters were rebuilt.

- 1527 Thomas Marshall becomes twenty sixth Abbot of St. Werburgh's until

1529, when he is succeeded by the penultimate abbot, John Birchenshawe (-1538)

- 1530 King Henry VIII recognised as Supreme Head of the Church of England.

- 1531 The 'great comet' (later to be known as Halley's Comet) arouses

a wave of superstitious fears throughout Europe

- 1533 Henry secretly marries Anne Boleyn (1501-1536) and is excommunicated by the

Pope. The Mayor of Chester, Henry Gee, ordered that "no manner person

or persons go abroade in this citie mumming in any place within the said

citie, their fayses being coveryd or disgysed (because) many dysordered

persons have used themselves rayther all the day after idellie in vyse

and wantoness then given themselves to holy contemplation and prayre the

same sacryt holye and prynsepaul feast." He also ordered that ale, beer

and wine were not to be sold after 9pm on any day or after Divine Service

on Sundays. The reforming Mayor Gee also had much to say regarding the

activities of Chester's citizens on the Roodee.

- 1535 Sir Thomas Moore, having refused the oath of the king's supremacy,

is tried for treason and executed.

- 1536 Catherine of Aragon died. Queen Anne Boleyn beheaded at the Tower

of London. Henry marries Jane Seymour.

- 1537 Chester's religious houses were suppressed on the

order of the Mayor, Ffoulk Dutton. At the dissolution there were 10 White

Friars, 7 Grey Friars, 5 Black Friars and 14 ladies at St.

Mary's Nunnery. Water was first brought from Boughton to the Bridgegate by lead pipes. Jane Seymour dies in childbirth; her son, the future King Edward VI, was created Earl

of Chester at his birth.

- 1538 Thomas Clarke becomes twenty eigth and final Abbot of St. Werburgh's

(-1540)

|

oregate

and Eastgate Streets lay on the line of Watling Street, the

Saxon name for the great Roman road which commenced at Dover, passed through

London and crossed the country to enter the fortress of Deva at the now-vanished

South Gate and leave by the Eastgate, the Porta Principalis Sinistra,

on its way to Manchester and York.

oregate

and Eastgate Streets lay on the line of Watling Street, the

Saxon name for the great Roman road which commenced at Dover, passed through

London and crossed the country to enter the fortress of Deva at the now-vanished

South Gate and leave by the Eastgate, the Porta Principalis Sinistra,

on its way to Manchester and York. origins, for example, that they

evolved from the structures that came to be erected, one row above another,

on the sloping piles of rubble that lined the main streets in the centuries

following the departure of the Legions and the destruction of the buildings

within their great fortress. Go

origins, for example, that they

evolved from the structures that came to be erected, one row above another,

on the sloping piles of rubble that lined the main streets in the centuries

following the departure of the Legions and the destruction of the buildings

within their great fortress. Go

This

old

Eastgate

was

a

massive

affair of high quality masonry of a cream-coloured sandstone,

which must have contrasted strikingly with the red stone which was the norm in the city. It comprised

a

single

pointed

arch

supporting

a

great

high

square

battlement

of

stone

with

octagonal

corner

turrets,

arrowslits

and

crenellations.

There were small flanking towers. The

tower

above

it

was

known

as

the Harre (Harry) Tower.

This

old

Eastgate

was

a

massive

affair of high quality masonry of a cream-coloured sandstone,

which must have contrasted strikingly with the red stone which was the norm in the city. It comprised

a

single

pointed

arch

supporting

a

great

high

square

battlement

of

stone

with

octagonal

corner

turrets,

arrowslits

and

crenellations.

There were small flanking towers. The

tower

above

it

was

known

as

the Harre (Harry) Tower.  (The name of Forest Street, incidentally- now Foregate Street- had, as is commonly claimed, nothing to do with it being the road to the forests that once thrived beyond the city but was a corruption of 'Fore-East Street'- the street before the Eastgate.)

(The name of Forest Street, incidentally- now Foregate Street- had, as is commonly claimed, nothing to do with it being the road to the forests that once thrived beyond the city but was a corruption of 'Fore-East Street'- the street before the Eastgate.)  In

the

18th

and

19th

centuries,

it

housed

a

society

going

by

the

splendid

name

of The

Honorable

Incorporation

of

the

King's

Arm's

Kitchen.

This came about as the result of an order by King Charles II that the custom of electing the mayor and his officers was to end. Sir Thomas Grosvenor was appointed as mayor, thus spawning an oligarchy between Eaton Hall (the Grosvenor residence) and Chester Corporation that would last until the Election Reform Act of 1832. The city's people were, unsurprisingy, increasingly unhappy with this imposition of an unelected mayor and Corporation, and one evening around the year 1770, a group of tradesmen met in a room in this pub and decided to form a City Assembly of their own, which

was

organised

(a wonderful idea) as

a

complete shadow assembly, a satirical

imitation

of

the

Corporation,

with

its

own

elected

mayor,

recorder,

town

clerk,

sheriffs, aldermen and common councilmen. They even had a replica of the mayor's sword and mace made for them. Their meeting room was fitted with beautiful, diamond shaped oak panels (said to have been fashioned from old pew doors from

In

the

18th

and

19th

centuries,

it

housed

a

society

going

by

the

splendid

name

of The

Honorable

Incorporation

of

the

King's

Arm's

Kitchen.

This came about as the result of an order by King Charles II that the custom of electing the mayor and his officers was to end. Sir Thomas Grosvenor was appointed as mayor, thus spawning an oligarchy between Eaton Hall (the Grosvenor residence) and Chester Corporation that would last until the Election Reform Act of 1832. The city's people were, unsurprisingy, increasingly unhappy with this imposition of an unelected mayor and Corporation, and one evening around the year 1770, a group of tradesmen met in a room in this pub and decided to form a City Assembly of their own, which

was

organised

(a wonderful idea) as

a

complete shadow assembly, a satirical

imitation

of

the

Corporation,

with

its

own

elected

mayor,

recorder,

town

clerk,

sheriffs, aldermen and common councilmen. They even had a replica of the mayor's sword and mace made for them. Their meeting room was fitted with beautiful, diamond shaped oak panels (said to have been fashioned from old pew doors from

The old Talbot was demolished and on its site rose The Royal

Hotel (illustrated right)

which

was

built

in

1784

by

one

John

Crewe,

who,

together

with

a

Mr Barnston

stood

for

Parliament

as

Whigs

against

Mr Thomas

Grosvenor

and

Mr

Richard

Wilbraham

Bootle

who,

as

Tories,

supported

William

Pitt.

The

two

seats

had

been

Grosvenor

family

'perks'

for

decades,

and

the

city

council

were

hand-in-glove

with

them.

The old Talbot was demolished and on its site rose The Royal

Hotel (illustrated right)

which

was

built

in

1784

by

one

John

Crewe,

who,

together

with

a

Mr Barnston

stood

for

Parliament

as

Whigs

against

Mr Thomas

Grosvenor

and

Mr

Richard

Wilbraham

Bootle

who,

as

Tories,

supported

William

Pitt.

The

two

seats

had

been

Grosvenor

family

'perks'

for

decades,

and

the

city

council

were

hand-in-glove

with

them. The Royal

Hotel was

the

opposition's

social

centre,

with

news

and

coffee

rooms

and

an

elegant

assembly

room

for

balls

and

concerts.

Earl

Grosvenor,

however,

had

the

last

laugh.

He

bought

the

building

and

in

1863,

had

it

totally

demolished,

and

replaced

by

the

much

larger

building

we

see

today-

and

named

it

after

his

family.

The Royal

Hotel was

the

opposition's

social

centre,

with

news

and

coffee

rooms

and

an

elegant

assembly

room

for

balls

and

concerts.

Earl

Grosvenor,

however,

had

the

last

laugh.

He

bought

the

building

and

in

1863,

had

it

totally

demolished,

and

replaced

by

the

much

larger

building

we

see

today-

and

named

it

after

his

family.