his account of a visit to Chester is from A year Abroad or Sketches of Travel in Great Britain, written by the American Willard C. George in 1852: his account of a visit to Chester is from A year Abroad or Sketches of Travel in Great Britain, written by the American Willard C. George in 1852:

"Chester, June 14. An hour's ride from Liverpool, through a delightful country, brought us to this place, one of the oldest and most remarkable towns in England. It derives its name, I am told, from the Latin word, castrum; and it is almost the only city in England where any remains of Roman art or industry have been preserved. It was the station of the twentieth Roman legion, and the old city is surrounded by a wall that was erected by Cymbeline in the century following the birth of our Saviour.

Right: walking the Walls on a crisp Autumn day in 2014

We first visited the Cathedral- a large, Gothic structure built in the seventh century. We entered the choir just as the organ commenced a stirring prelude to the noon-day service, and the people had gathered in the chapel to offer up their prayers, and sing God's praise. How those organ-tones echoed from arch to arch, and pealed along those vast walls and aisles; I could not help feeling that God could truly be worshipped there, although before me were altars erected by superstition, and in the nunnery, sadder evidence still, that many had been led from duty and the world, to become the victims of false religious theories.

After the service, we were allowed to visit the chapel. Its walls are covered with magnificent paintings and carved work, the floor is of marble, laid in mosaic, and on each side are large windows of stained glass, embellished with paintings on scriptural subjects. Near the centre, is the tomb of Henry IV., a German Emperor, who, weary of the world, and, especially, of governing unruly subjects, sought a refuge here in Chester, where he spent the last years of his life in retirement, and was buried in the Cathedral.

In making the circuit of the wall, a distance of three miles, we entered several of the towers, in one of which is a pretty museum; but none interested me so much as the tower of King Charles. We entered it by a short stairway, and read over the door these words: "King Charles stood on this Tower, Sept. 24, 1645, and saw his army defeated on Rowton Moor." We stood on the same spot and looked out upon Rowton Moor, where the fierce Protector struck the blow that forever crushed the hopes of Charles I. But how different were our feelings, as we surveyed the calm and beautiful landscape, from the deep suspense and agony of the unfortunate king, as he watched the events of that day.

Under the Water Tower, our guide showed us the dungeon in which two daughters of the Earl of Derby were confined at the time he was executed. Nothing can exceed the beauty of the landscape from this point; the extended plain dotted with all kinds of trees, shrubs and flowers, cut into all shapes by the dark lines of hawthorn; the Race courses and the serpentine Dee on the left, and the gentle ridges on the right, that rise higher and higher until they are lost in the lofty mountains of Wales, altogether form a picture of rural beauty that stands in novel contrast with the gray and dingy old town.

Near the eastern gate of the city stands the old Castle, which was once occupied by Julius Cesar. It has been very much enlarged since that time, and is now occupied by British soldiers. On the other side of the Dee, we were shown a cave where King Edgar received tribute from twelve dependent kings of Britain in 971. The house in which he lodged stands near the bank of the river, and on its front wall is a large painting, representing the barge in which they rowed him down the river to his subterranean retreat. Near the eastern gate of the city stands the old Castle, which was once occupied by Julius Cesar. It has been very much enlarged since that time, and is now occupied by British soldiers. On the other side of the Dee, we were shown a cave where King Edgar received tribute from twelve dependent kings of Britain in 971. The house in which he lodged stands near the bank of the river, and on its front wall is a large painting, representing the barge in which they rowed him down the river to his subterranean retreat.

We passed through the "Rows" in the midst of all the fashion and beauty of Chester. These "Rows" are nothing more than extensive arcades, running through many streets, and elevated several feet above the ground.

There is one singular fact connected with Chester, that has never been explained. Its streets, as in other towns, are not on the surface of the ground, but they are actually ravines, several feet deep, cut through the solid earth and rock. Antiquarians have been puzzled to find a reason for this. The most reasonable conclusion is that it was connected with some plan of defence not well understood. Chester was exposed to the sudden inroads of the Welch, the same as New Castle and Carlisle were subject to attacks from the Scotch on the north.

After we had seen every thing of interest in the old town, we crossed the Dee over a magnificent bridge, consisting of a solid arch of masonry, more than four hundred feet across the river. It is said to be the widest stone arch in England, probably, in the world. We only had time to pass through the magnificent gate leading to Eaton Hall, and ramble among green lawns, and fragrant groves fifteen minutes, and then the gate-keepers' call reminded us that we must leave the park, and finish our day's adventure".

The short excerpt following is from The Life and Opinions of General Sir Charles James Napier, G.C.B. by Sir William Francis Patrick Napier (his brother), written in 1857. The short excerpt following is from The Life and Opinions of General Sir Charles James Napier, G.C.B. by Sir William Francis Patrick Napier (his brother), written in 1857.

Napier (1782-1853) was a general of the British Empire and the British Army's Commander-in-Chief in India, notable for conquering the Sindh Province in what is now Pakistan. He put down several insurgencies in India during his reign in India, and once said of his philosophy about how to do so effectively: "The best way to quiet a country is a good thrashing, followed by great kindness afterwards. Even the wildest chaps are thus tamed".

"May 2nd. This is a fine old town. 'The Rows' are very curious and antiquarians have exhausted conjecture on the subject; none of them seem to think they were built to keep people from wet, but have accidentally taken this form: they are very convenient.

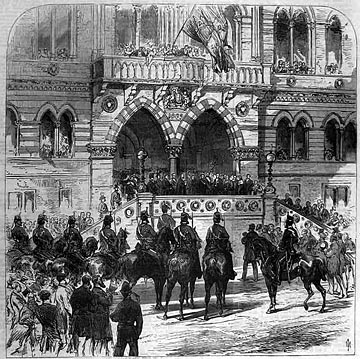

"May 4th. All the world and his wife racing. The scene is beautiful, the old walls overlook the course and are crowded, while below are booths, punch and judy, swings, men and women, drunk, and sober; and the old river Dee glides on his course, his waters and those wild rioters on his banks running alike to the ocean of futurity, to be lost and heard of no more, going, going, gone! All the rogues, and fools and drunkards in the country seem collected, and the Row balconies are filled all day with idlers and well-dressed girls, young and old, looking into the streets from daybreak till dark. Such idleness I never witnessed as at Chester. My life has been long, it has but twelve years to run, and yet I never, in any country, witnessed such stupid idleness as in Chester. Those who go to the course have some fun, but those who hang over the Row-balconies all day like old clothes, see nothing, hear nothing, do nothing."

He did live for exactly another twelve years! This Wikipedia article tells more about his fascinating life and sayings.

This lengthy, but fascinating, account is from The English at Home (a geologist's visit to Chester) by the French writer, politician- and amateur geologist Henri-François-Alphonse Esquiros (1812-1876) and was published in 1861. His Wikipedia page is here. This lengthy, but fascinating, account is from The English at Home (a geologist's visit to Chester) by the French writer, politician- and amateur geologist Henri-François-Alphonse Esquiros (1812-1876) and was published in 1861. His Wikipedia page is here.

"Chester resembles no other town in England, and I have seen nothing like it on the Continent. This city is a museum: the Celtic era, the Norman period, the middle ages, the religious reform, and the renaissance, engraved reminiscences on this new red sandstone, where extinct animals had already left traces of their passage. With its buildings of soft and friable stone crumbling in the wind, with its old bending houses- its chronicles of another age- Chester speaks at each footstep to the traveller of the fragility of human things and the ravages of time: but it speaks of them philosophically. This language of the stones has nothing in it sad and despairing; on the contrary, it bears to the most perturbed hearts a feeling of peace and soft melancholy. There is so much repose in these streets, which are not agitated by the buzz of business; so much grave quietude in the old building; so much calmness and pleasant affability in the faces! The dress of the ladies, though elegant, has even a quiet character; their summer dresses may be fresh and cheerful, but they are simple. Chester is the metropolis of the district in which agriculture flourishes, and the two portions of the city which, before all, demand the visitor's attention, are the city wall and the Rows.

The ramparts of Chester constitute the sole model still existing in England of the old mode of fortification. It is a high wall, wide enough for two persons to walk abreast, and runs round the whole town. Built during the middle ages, this wall rests on the foundations of an older one constructed by the Romans. You may still see, at more than one spot, the base of the Roman erection which served as the root of the modern works. Thus enclosed in a corset of red sandstone, the city could neither extend nor grow larger. The ramparts of Chester form an agreeble promenade, probably unique in the world: these fortifications, cut in the rock and raised to destroy the life of man, now serve to prolong it, for convalescents, old persons, and delicate ladies come here to breathe the pure air and enjoy the freshness of the scenery. The ramparts of Chester constitute the sole model still existing in England of the old mode of fortification. It is a high wall, wide enough for two persons to walk abreast, and runs round the whole town. Built during the middle ages, this wall rests on the foundations of an older one constructed by the Romans. You may still see, at more than one spot, the base of the Roman erection which served as the root of the modern works. Thus enclosed in a corset of red sandstone, the city could neither extend nor grow larger. The ramparts of Chester form an agreeble promenade, probably unique in the world: these fortifications, cut in the rock and raised to destroy the life of man, now serve to prolong it, for convalescents, old persons, and delicate ladies come here to breathe the pure air and enjoy the freshness of the scenery.

In Eastgate-street I went up a flight of steps that led to a bridge and thence to the city wall: it was curious to look down at the houses leaning at the base of the old wall, into yards, gardens full of grass and verdure, where frail creepers threw their delicate shoots and flowers over the age-worn masonry; but you must advance a little for the view to expand. Here the eye follows for a long distance the windings of the Dee, proceeding to its mouth: there is the deep bed of a canal cut through the solid bed of red sandstone; and, indeed, nothing is more beautiful than the ocean of valleys and meadows surrounding Chester, save the savage pride of the Welsh mountains, visible in the distance.

These mountains, standing erect in their tranquil majesty, display another system, or, to speak more correctly, another age of nature, from the rock of which Chester wall was built, and the gloomy masses of slate seem to despise the red sandstone as an upstart, for the nobility of rocks, like that of men, lies in the antiquity of their origin. Seen from Chester wall, the Welsh mountains are blended with the farthest sky line, and in truth might, themselves, be taken for clouds hardened into stone. This comparison may, perhaps, appear insulting to the monuments of nature which represent strength and stability; but, geologically regarded, mountains are not protected from vicissitudes, and pass with ages from one shape into another. The wind disperses the cloud which changes, and time alters the mountain.

On this city wall I met a man of about fifty, who was contemplating with thoughtful eye the solemnities of nature and the past. He was an ex parish clerk, compelled to resign his office owing to a disease which had weakened his eyesight; he was not a professional antiquarian, and yet it was easy to recognise in his language a sincere and assiduous admirer of the venerable relics of history. According to him, there was only Chester in the world, and I confess that momentarily I shared his enthusiasm. Though poor and meanly clad, he was an optimist: at the sight of the old memorials which recalled recollections of feudalism, the bloody wars of religion, and the times of ignorance, he burst into ecstasies at the happiness of living in an enlightened age. I have no liking for ciceroni, but this man was not a professional one. "I am," he told me, " a native of the city. Formerly I spent my leisure hours in studying old histories of Chester, but now I have bad eyesight, and this walk is my book, and I find here, written in legible characters, the happy changes which time has introduced into human institutions. That old tower you see down there is Water Tower, an old fortress erected to repulse maritime foes, for at that period an arm of the river flowed under this portion of the walls, and vessels could sail up to the foot of the tower. Now-a-days, thank Heaven, there is no enemy and no water; our age has no need of the military works which make the mind revert to scenes of carnage. That other square tower, which received the name of Bonwaldesthorne's Tower, and which stands there blood-hued beneath its mantle of ivy, is now the museum of the Mechanics' Institution. The contrast between the murderous intention of that edifice and the use made of it in modern times, victoriously opposes the gentle and practical manners of our age to the gloomy genius of the thirteenth century. This again is Phoenix Tower; from the top of that ruin Charles I. saw the defeat of his army on September 24, 1645, by the Parliamentary troops on Rowton Moor. I am only a poor man, and have a hard matter to gain a living, but when I look with a light heart at the splendid scenery surrounding us, and think of the painful impressions the same beauties of nature must have produced on the downcast monarch, I thank Heaven for not having made me a king in those sad times. And then to think of the calmness which has succeeded such ravages! The destructive elements have themselves abandoned the field to the useful arts and the amusements of man. This splendid meadow, undulating to such a distance, and on which oxen are tranquilly grazing, is called the Roodee: formerly it was a lake, now it is devoted to gymnastics, cricket, and races. On this city wall I met a man of about fifty, who was contemplating with thoughtful eye the solemnities of nature and the past. He was an ex parish clerk, compelled to resign his office owing to a disease which had weakened his eyesight; he was not a professional antiquarian, and yet it was easy to recognise in his language a sincere and assiduous admirer of the venerable relics of history. According to him, there was only Chester in the world, and I confess that momentarily I shared his enthusiasm. Though poor and meanly clad, he was an optimist: at the sight of the old memorials which recalled recollections of feudalism, the bloody wars of religion, and the times of ignorance, he burst into ecstasies at the happiness of living in an enlightened age. I have no liking for ciceroni, but this man was not a professional one. "I am," he told me, " a native of the city. Formerly I spent my leisure hours in studying old histories of Chester, but now I have bad eyesight, and this walk is my book, and I find here, written in legible characters, the happy changes which time has introduced into human institutions. That old tower you see down there is Water Tower, an old fortress erected to repulse maritime foes, for at that period an arm of the river flowed under this portion of the walls, and vessels could sail up to the foot of the tower. Now-a-days, thank Heaven, there is no enemy and no water; our age has no need of the military works which make the mind revert to scenes of carnage. That other square tower, which received the name of Bonwaldesthorne's Tower, and which stands there blood-hued beneath its mantle of ivy, is now the museum of the Mechanics' Institution. The contrast between the murderous intention of that edifice and the use made of it in modern times, victoriously opposes the gentle and practical manners of our age to the gloomy genius of the thirteenth century. This again is Phoenix Tower; from the top of that ruin Charles I. saw the defeat of his army on September 24, 1645, by the Parliamentary troops on Rowton Moor. I am only a poor man, and have a hard matter to gain a living, but when I look with a light heart at the splendid scenery surrounding us, and think of the painful impressions the same beauties of nature must have produced on the downcast monarch, I thank Heaven for not having made me a king in those sad times. And then to think of the calmness which has succeeded such ravages! The destructive elements have themselves abandoned the field to the useful arts and the amusements of man. This splendid meadow, undulating to such a distance, and on which oxen are tranquilly grazing, is called the Roodee: formerly it was a lake, now it is devoted to gymnastics, cricket, and races.

"Still," the old antiquary added, "we must be just; we must allow that if the neighbourhood has gained much agriculturally, the city itself has lost commercially. There was a time when Chester was a flourishing port; but rivers change, and, owing to the fickleness of the Dee, navigation has withdrawn. Liverpool has reaped this rich harvest. The Dee consoles itself, as you can see, by keeping its girdle of pretty cottages and villas, its old romantic bridge, its fresh and leafy groves, its pleasure-boats, and, above all, its mills, which are great antiquities. It has also had the honour of being sung in verse by Drayton, Browne, Spenser, and Milton, who gave it the epithets of' divine,' ' enchanting,' and ' wizard.'

"I was certain that something pleasant would happen to me to-day, for my wife threw a shoe after me as I went out. You cannot, in fact, credit the pleasure I feel in speaking of the history of Chester with any one who takes an interest in it. Being a very ancient city, my home has retained many customs and traditions of the past, and is rich in chronicles. At Newgate, where we now stand, there was formerly a postern called Wolfsgate, or Peppergate. In the sixteenth century, the Mayor of Chester had a daughter, who was playing at ball in Pepperstreet with some other young girls: one day she was carried off by her lover, and the father, clever too late, ordered the gate of the city to be closed through which the escape took place. Hence the proverb existing in Chester: ' Shut the postern when the girl is carried off.'

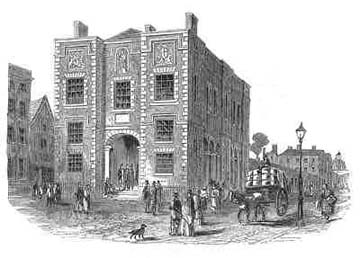

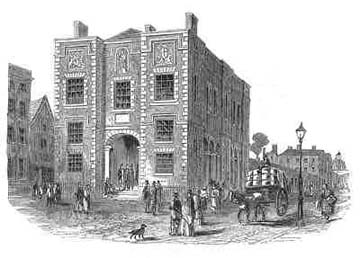

"Formerly the inhabitants of Chester were distinguished for a very lively taste for dramatic representations: it may even be said that our city was the cradle of the English stage. Another source of amusement that attracted a great many strangers was the fair, and it was a custom during this fair that a glove should be hung up in the town hall and afterwards on the roof of St. Peter's church. To understand the meaning of this emblem, you must know that Chester was celebrated for centuries for its manufacture of gloves, and that in the time I speak of trade was not free; the right of carrying on any traffic was a privilege reserved solely for citizens born within the city. During the fair, on the contrary, everybody might set up as a trader, and the glove hung up was the signal that proclaimed the temporary liberty. The custom had lasted for centuries, when the Reform Bill, that just and obstinate foe of ancient monopolies, extended the rights throughout the whole year to all strangers and townsmen. The authorities of the city still continued for some time to hang up the old banner outside the wall. I have myself seen this public ceremony- a reminiscence of another age- and it is only during the last twenty years that the custom has been abolished." "Formerly the inhabitants of Chester were distinguished for a very lively taste for dramatic representations: it may even be said that our city was the cradle of the English stage. Another source of amusement that attracted a great many strangers was the fair, and it was a custom during this fair that a glove should be hung up in the town hall and afterwards on the roof of St. Peter's church. To understand the meaning of this emblem, you must know that Chester was celebrated for centuries for its manufacture of gloves, and that in the time I speak of trade was not free; the right of carrying on any traffic was a privilege reserved solely for citizens born within the city. During the fair, on the contrary, everybody might set up as a trader, and the glove hung up was the signal that proclaimed the temporary liberty. The custom had lasted for centuries, when the Reform Bill, that just and obstinate foe of ancient monopolies, extended the rights throughout the whole year to all strangers and townsmen. The authorities of the city still continued for some time to hang up the old banner outside the wall. I have myself seen this public ceremony- a reminiscence of another age- and it is only during the last twenty years that the custom has been abolished."

Before leaving me, this amiable enthusiast recommended me, before all, to visit the Rows; and they are, in fact, one of the curiosities of Chester, nothing like them, probably, existing in the known world. Each side of the street has two rows of shops, one on the ground the other on the first floor, and there is a communication by upper galleries with those above. These galleries, reached by stone steps standing at regular distances, are what are called the Rows: the roofs of the bottom shops form the platform on which you walk, and which runs regularly from house to house all along the street. On one side, the roof of the gallery is supported by wooden pillars, more or less carved; on the other, it rests upon the front of the shops. The first floor shops are let at a higher rent than those below, and are also more ornamented. These cloisters render thus more than one service; thanks to them, the inhabitants can go from one end to the other of the street without exposing themselves to rain or mud. These sheltered and hanging streets suit the humour of the lounging traveller; he can walk about, stop before the shop windows, or, leaning over the wooden balustrade, watch what goes on in the street. For the artist, such passages, imprinted with a character at once elegant and cenobitic, possess the charm of novelty.

Externally, this first floor, open to the street, and along which people walk, gives a strange appearance to the architecture of the houses ; inside, the old arcades, in which the light is discreetly tempered, are equally characteristic. The general style of the Rows is enhanced by the very old wooden houses which set it in; and they have suffered very slightly from works of repair. The origin of the Rows has been a hard nut for antiquaries to crack. According to some, they were means of defence at a time when Chester was necessarily exposed to the sudden invasions of the Welsh, and especially to cavalry charges. Others insinuate, no doubt in jest, that these galleries were built to protect sensitive females from meeting horned animals. It is Pennant's opinion that the prototype of this style of architecture will be found in the Roman vestibules or porticos, but, however this may be, it is certain that the city of Chester has best of all understood the English climate. After that, you are amazed to find umbrella sellers there.

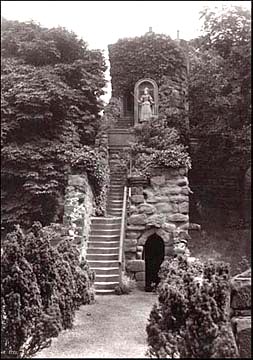

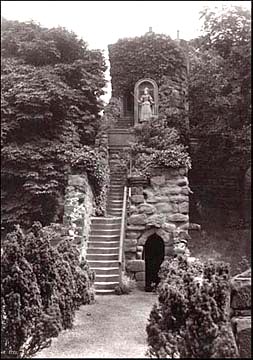

Though the majority of the houses is built of brick or wood, the relations of geology with the architecture of towns may be specially studied at Chester. All the old edifices are built of new red sandstone, and the most admirable of all are the cathedral and St. John's church, which offers a few remains of Norman architecture. It is, besides, curious to see how art has been brought to agree with the character of the stone; the red sandstone being a tender material which crumbles under the hand of time, the architects have paid no attention to details or ornaments: they are rather painters than sculptors. The mediaeval buildings, in truth, assume an august appearance through the mass, the colour, and the effects of light and shade. Nothing is more majestic than the cathedral tower seen from a distance, and which, even under a cloudy sky, seems floating in a perpetual sunset. Age gives this stone, coloured by oxide of iron, a ruinous appearance, which does not injure the effect. You find at Chester old ruins of chapels, towers, keeps, which have retained no other shape than that of the rock, but which, enlaced by the creeping ivy, bear a haughty and noble air even in their decadence. These red spectres of the past add an interesting character to the city, which has fallen asleep in the tranquillity of a happy old age. Though the majority of the houses is built of brick or wood, the relations of geology with the architecture of towns may be specially studied at Chester. All the old edifices are built of new red sandstone, and the most admirable of all are the cathedral and St. John's church, which offers a few remains of Norman architecture. It is, besides, curious to see how art has been brought to agree with the character of the stone; the red sandstone being a tender material which crumbles under the hand of time, the architects have paid no attention to details or ornaments: they are rather painters than sculptors. The mediaeval buildings, in truth, assume an august appearance through the mass, the colour, and the effects of light and shade. Nothing is more majestic than the cathedral tower seen from a distance, and which, even under a cloudy sky, seems floating in a perpetual sunset. Age gives this stone, coloured by oxide of iron, a ruinous appearance, which does not injure the effect. You find at Chester old ruins of chapels, towers, keeps, which have retained no other shape than that of the rock, but which, enlaced by the creeping ivy, bear a haughty and noble air even in their decadence. These red spectres of the past add an interesting character to the city, which has fallen asleep in the tranquillity of a happy old age.

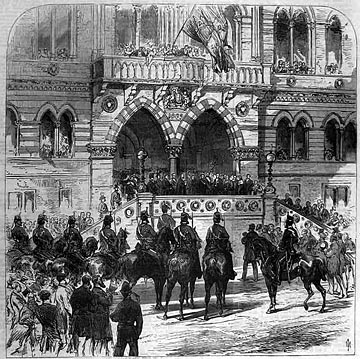

Right: American visitors admiring the view from the Northgate

I was obliged to tear myself from Chester not without a pang, for after studying the new red sandstone at the different spots where the history of this rock is written, the natural order of events made me proceed through the splendid royal forest of Delamere to Northwich, where I should find the salt mines and springs. Salt is extracted from the sea, springs, and mines, and Great Britain has, then, these resources ready to hand. The sea surrounds it; in the interior, the salt water springs bubble up; and the mines of rock are hollowed beneath the verdurous soil of Cheshire and Worcestershire".

In his work Ten Day's Tourist; or Sniffs of The Mountain Breeze published in 1865, William Bigg of Luton, Bedfordshire has left us the following description of Chester: In his work Ten Day's Tourist; or Sniffs of The Mountain Breeze published in 1865, William Bigg of Luton, Bedfordshire has left us the following description of Chester:

"This, perhaps most ancient city in the Kingdom, is in some of its features quite unique. The old wall of defence remains nearly perfect; and a pleasant walk of two or three yards wide on the top of it leads from the centre of one of the principle streets round among housetops, through gardens and orchards, whose pear trees throw up their fruit-laden branches to a level with the parapet: along the precipitous bank of the river [canal] moat, past an ancient look-out tower, now used as an observatory, at a point commanding a wide view of town and country; and along by a fragment of an ancient fortification, converted into a museum of a scientific institute; till at length that beautiful amphitheatre of the Roodeye, the Chester racecourse, stretches into view, its magic circle bounded by a grand stand of nature's own making.

Beyond this there is the singlespan stone bridge over the river Dee, a marvel of elegance, expansion, and symmetry. The special peculiarity of Chester is, however, the 'Row'. In the ancient streets intersecting at the heart of the city, the foot-way for passengers runs through what was originally the ground floor of the houses on each side of the road, the basement storey now fronting on to the carriage way beneath. The shops under this singular arrangement, are set back into what, under ordinary circumstances would have been the back parlour of the establishment; and the public walk under the ceiling of the floor of the drawing-room or best sleeping chamber above. Once landed in one of these Rows, the fair sex may do their shopping without parasol or umbrella, having a good house over-head, and at the same time an open look out over the public street, and an unrestricted circulation of fresh air.

There are about Chester many old houses worth looking at for their quaint exterior, and curious history. The fish and vegetable market, as in every strange town, is also worth a peep. In the streets the Welsh costume of many of the country people reminds you that you are still in the near neighbourhood of Cambria; from whose lakes and mountains you will return with, I doubt not, fresh braced nerves and energies renewed to your professional engagements, prepared to fight with greater vigour and brighter cheerfulness the great battle of life"

Charles Kingsley (1819-1875). In 1869 the good people of Chester received news of the Devil coming to town. Moreover, he was booked for a long stay! There was understandably some consternation. The Devil had assumed an earthly guise- that of Charles Kingsley, known to us as the author of The Water Babies but in his time he was the 'Red Canon' of the mid-Victorian era- a Christian Socialist, Chartist supporter, friend of trade unions and similar heretical ideas. Charles Kingsley (1819-1875). In 1869 the good people of Chester received news of the Devil coming to town. Moreover, he was booked for a long stay! There was understandably some consternation. The Devil had assumed an earthly guise- that of Charles Kingsley, known to us as the author of The Water Babies but in his time he was the 'Red Canon' of the mid-Victorian era- a Christian Socialist, Chartist supporter, friend of trade unions and similar heretical ideas.

Kingsley preached such incendiary ideals as universal brotherhood, equality for women, giving all your worldly wealth to the poor, and so forth, which was all very well in church on a Sunday, but was felt to be a bit impractical for daily life - not to say downright dangerous!

The author of these high-flown principles had begun his career as a radical-minded crowd-puller with fiery speeches and a series of pamphlets on the political themes of the day. He had become a leading light in the Chartist movement and was always in the van of their marches and demonstrations. His rousing speeches at their rallies had alarmed the upper classes with nightmare visions of the revolutionary mobs surging up the Mall and a guillotine in Trafalgar Square.

As the Chartist campaign quietened, Kingsley had advanced his position in the Church of England. While still sponsoring minority causes, he had also turned to literature and began to make a name for himself as an author, producing in 1850 his first novel Alton Locke, followed in 1851 by Yeast, both dealing with contemporary social problems in a forthright way. In Hypatia (1853) he had dealt with the highly intellectual subject of early Christianity in conflict with Greek philosophy at Alexandria. In 1855 had come the very different Westward Ho!, that rousing adventure of Elizabethans on the Spanish Main. In 1863, there appeared what is probably his best known title, The Water Babies, and in 1866 Hereward the Wake, a tale of Saxons versus their Norman overlords in medieval England. In between these works he continued to write for publications such as Christian Socialist and Politics for the People.

The surprising thing was, that with all his revolutionary writings, Kingsley was well received at Court, being Chaplain to the Queen and tutor to the Prince of Wales. In 1860 he was appointed to the Professorship of Modern History at Cambridge, which he held until 1870.

Such then, was the firebrand who now descended upon peaceful Chester. But the natives need not have worried. Like many rebels, Kingsley's fire had cooled to a mere glow with the passing years, and the slow realisation that life and humanity are infinitely more complex than they appear in the bright light of youthful idealism. Literature and scientific studies were now his priority. He was to spend his three years in Chester very happily. As his wife Mary commented: "My husband likes his cathedral services, especially the twice daily ones. He feels his soul at anchor in those two hours. Afterwards he can take refuge in the Chapter and Library Room when we are likely to be invaded at the Residence. There he is safe from the eager parties of Americans whose first desire, after disembarking at Liverpool, is to move inland in search of the oldest thing they can find, ie, the Cathedral."

He himself later remarked of his time in Chester "I do love this place and people and long to be back (in Abbey Square) for our Spring residence".

Kingsley's sermons drew large congregations, and soon, when people discovered that he did not sprout a pair of horns after all, they grew to love him. Although he was to spend only three months of each of the three years in Chester, his impact on the community was considerable.

Keenly interested in the sciences and in cultural activities, he decided to raise money for the City Library by starting evening classes in botany. Advertised at 3d for the evening, the idea attracted 40 young people of both sexes. The presence of women, however, alarmed Kingsley. Although he had in the past supported women's rights, he did not favour the idea that both sexes should learn together. As he said: "The presence of young ladies might prove too strong a counter attraction. Let Mr John Price take the ladies. He is the nicest man and should have the nicest pupils." Keenly interested in the sciences and in cultural activities, he decided to raise money for the City Library by starting evening classes in botany. Advertised at 3d for the evening, the idea attracted 40 young people of both sexes. The presence of women, however, alarmed Kingsley. Although he had in the past supported women's rights, he did not favour the idea that both sexes should learn together. As he said: "The presence of young ladies might prove too strong a counter attraction. Let Mr John Price take the ladies. He is the nicest man and should have the nicest pupils."

Soon the two classes had grown, and Kingsley was leading parties of more than a hundred out into the countryside for fieldwork. Eventually a special train was hired for a full day out to places of interest further afield. All the students, even from different social classes, travelled together, returning at the end of the summer's day "refreshed, inspired, with nosegays of wild flowers and happy thoughts of God's earth and of their fellow creatures."

These classes led to the formation of the Chester Natural History Society, which met in its member's homes until the Grosvenor Museum was built. The Society shared in the museum's management, held classes and lectures and contributed the natural history gallery. The splendid Grosvenor Museum continues to thrive today, these duties now being the responsibility of the city council. A marble bust of its founder can be seen today in the entrance to the Natural Sciences Gallery.

The time came when Kingsley had to write to the Society's Secretary that "the programme of your Society for the year makes me at once proud and envious. For now I have to tell you that I have just accepted the vacant stall at Westminster, and shall in a week or two be Canon of Chester no longer. Had I been an old bachelor, I would never have left Chester. Shall we go up Hope Mountain, or the Halkin together again, with all those dear, courteous, sensible people? My eyes filled with tears when I think of it."

It was the Prime Minister, William Gladstone who recommended him for Westminster, and he was never to return to Chester.

In 1873 he published Town Geology, a work based upon his many tours of Chester with his students, and in 1874 came his final work, Prose Idylls. One of his most evocative poems spelling his love for the countryside goes:

Leave to Robert Browning

Beggers, fleas and vines;

Leave to Squeamish Ruskin

Popish Apennines,

Dirty stones of Venice

And his gas lamps seven;

We've the stones of Snowdon

And the lamps of Heaven. |

Always of a highly nervous temperament, his over-exertion resulted in repeated failures of health, and he died in 1875 at the age of 56. Though hot-tempered and combative, he was a man of singularly noble character. His type of religion, cheerful and robust, was described as 'muscular Christianity'. Strenuous, eager, and keen in feeling, he was not either a profoundly learned, or perhaps very impartial, historian, but all his writings are marked by a bracing and manly atmosphere, intense sympathy, and great descriptive power. His

poem, The Sands of Dee (from his first novel, Alton Locke) captured the melancoly atmosphere of the treacherous deserted flats and wastes of shifting sands where once Chester's mighty river flowed:

Oh Mary, go and call the cattle home,

And call the cattle home,

And call the cattle home

Across the sands of Dee;

The western wind was wild and dank with foam,

And all along went she.

The western tide crept up along the sand,

And o'er and o'er the sand,

And round and round the sand,

As far as eye could see.

The rolling mist came down and hid the land:

And never home came she. |

Oh! is it weed, or fish, or floating hair-

A tress of golden hair,

A drowned maidens hair

Above the nets at sea?

Was never a salmon yet that shone so fair

Among the stakes on Dee.

They rowed her in across the rolling foam

The cruel crawling foam,

The cruel hungry foam,

To her grave beside the sea;

But still the boatmen hear her call the cattle home

Across the sands of Dee. |

Canon Kingsley was a vehement opponent of Chester Races. He described racegoers as "knaves and black fools", prone to wriggle out of their responsibilities with far-fetched excuses. Aiming his attack at the 'young men of Chester', the good Canon put forward some interesting opinions on the evils of betting, a means, he contended, of procuring money out if a neighbour's ignorance, "If you and he bet on any event, you think that your horse will win; he thinks his will, or he knows the winner. In plain English, you think that you know more about the matter and try to take advantage of his ignorance".

Lewis

Carroll (Charles

Lutwidge

Dodson: 1832-1898) was

born

at

the parsonage in Daresbury,

a

few

miles

from

Chester,

in

1832.

Familiar

to

us

all

is

this

scene

from

his

immortal Alice

in

Wonderland published

in

1865: Lewis

Carroll (Charles

Lutwidge

Dodson: 1832-1898) was

born

at

the parsonage in Daresbury,

a

few

miles

from

Chester,

in

1832.

Familiar

to

us

all

is

this

scene

from

his

immortal Alice

in

Wonderland published

in

1865:

"Please

would

you

tell

me'

said

Alice

a

little

timidly,

for

she

was

not

quite

sure

whether

it

was

good

manners

for

her

to

speak

first,

'why

your

cat

grins

like

that?'

'It's

a

Cheshire

cat'

said

the

Duchess;

'and

that's

why.'

'I

didn't

know

that

Cheshire

cats

always

grinned;

in

fact,

I

didn't

know

that

cats could grin.'

'They

all

can,'

said

the

Duchess;

'and

most

of

'em

do".

We

all

imagine

this

Cheshire

cat

to

be

an

invention

of

Carroll's

fertile

imagination,

but

it

is

mentioned

in

Charles Kingsley's Water

Babies, published

two

years

earlier

in

1863:

"The

otter

grew

so

proud

that

she

turned

head

over

heels

twice,

and

then

stood

upright

half

out

of

the

water,

grinning

like

a

Cheshire

cat".

The Wordsworth

Dictionary

of

Proverbs lists

at

least

two

earlier

examples:

in

Peter Pindar's Pair of Lyric Epistles of

1795

we

have,

"Yet,

if

successful,

thou

wilt

be

adored-

Lo,

like

a

Cheshire

cat

our

Court

will

grin!"

(Peter Pindar was a pseudonym of John Wolcot, or Wolcott, who died in 1819)- and

also

in

Scott's Family

Letters of

1855:

"Ever

since

the

Polts

have

grinned

at

me

like

so

many

Cheshire

cats".

The

Cheshire

Cat

is

known

to

go

back

much

further

in

time

and

is,

curiously,

associated

with

the

making

of our delicious Cheshire

cheese.

It

is

recorded

that

part

of

the

process

would

involve

cutting

the

cheese

into

what

looked

like

the

smile

of

a

cat-

hence

the

'grin'

of

the

Cheshire

This website

will

tell

you

all

you

want

to

know

about

Lewis

Carroll's

birthplace

and

the

village

of

Daresbury.

Many years before the 'Alice' stories were given life, cats gave rise to more than a little trouble in the famous streets of Chester. In 1815, Napoleon Bonaparte was firmly banished to St. Helena. A large number of what was known as 'genteel families' plus a contingent of the British Army were detailed to accompany him. King George III's minister, somewhat distressed by the infestation of rats on the isle, decided firm steps were necessary to eradicate the menace and to this purpose it was agreed to purchase as many cats and kittens as could be delivered in the time allotted before sailing. Consequently, handbills were circulated throughout the land and on the streets of Chester. These are the rates advertised for the aquisition of said felines:

16/- for an athletic fully grown Tom.

l0/- for an adult female puss.

2/6 for every kitten.

Three days later, at the appointed time and place, there converged a great multitude, all carrying sacks containing squirming, shrieking felines, nearly 3,000 in all. Soon the gathering was so numerous it was difficult to move, tempers flared, fights broke out and sacks were dropped, disgorging the hissing, scratching contents onto the streets of Chester.

The citizens watching from their windows, who were at first bemused by this event now suddenly found themselves under siege by a plague of cats- followed by, in many cases, the canine population of the city- through the windows, along the balconies, across the drawing rooms, shattering in a million pieces china and glass and leaving a wake of total destruction. The citizens watching from their windows, who were at first bemused by this event now suddenly found themselves under siege by a plague of cats- followed by, in many cases, the canine population of the city- through the windows, along the balconies, across the drawing rooms, shattering in a million pieces china and glass and leaving a wake of total destruction.

Retribution was swift, however, and soon no cat was safe- wherever puss was seen, reprisals were taken. The engagement lasted for hours until finally the moggies took rout. A few managed to escape, but for most a watery grave was to be their ignominious end, and the next day more than 500 were counted floating in the River Dee.

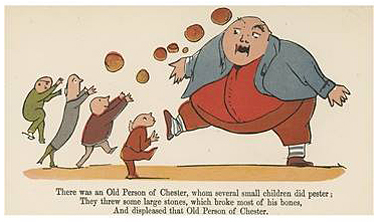

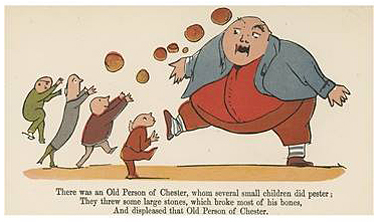

Left: some Chester nonsense from Edward Lear

A contribution from 'R S B' in the Cheshire Sheaf: "Hunting cats is not now on the list or regular field sports, but that it used to be favoured is shown by the issue in 1253 of a royal licence to Davis de Monte Alto of Mold to hunt with his own dogs hares, foxes and cats throughout all the forests of Cheshire and the conquered parts of Wales. This was not to be done in warrens or during the months when the deer were breeding and the King's 'great deer' were not to be taken" (Cal. Pat. 10 Jan. 1253)

In “The Letters of Charles Dickens”, edited by his sister-in-law and eldest daughter, there appears a characteristic letter addressed to the latter under the name of Mamie, and written from Chester on the day of his public reading there: In “The Letters of Charles Dickens”, edited by his sister-in-law and eldest daughter, there appears a characteristic letter addressed to the latter under the name of Mamie, and written from Chester on the day of his public reading there:

"Chester, Tuesday, Jan. 22nd, 1867. My dearest Mamie, We came over here from Liverpool at eleven this forenoon. There was a heavy swell in the Mersey breaking over the boat; the cold was nipping, and all the roads we saw as we came along were wretched. We find a very moderate let here; but I am myself rather surprised to know that a hundred and twenty stalls have made up their minds to the undertaking of getting to the hall.

This seems to be a very nice hotel (The Queen, which still thrives opposite the Railway Station), but it is an extraordinarily cold one. I have seldom seen a place look more hopelessly frozen up than this place does. The hall (the Music Hall) is like a Methodist Chapel in low spirits, and with a cold in its head. A few blue people shiver at the corners of the streets. And this house (the hotel), which is outside the town, looks an ornament on an immense twelfth cake baked for 1847.

I am now going to the fire to try and warm myself, but have not the least expectation of succeeding. The sitting-room has two largo windows in it, down to the ground and facing due east. The adjoining bedroom (mine) has also two large windows in it, down to the ground and facing due east. The very large doors are opposite the large windows, and I feel as if I were something to eat in a pantry,"

In two letters written a couple of days afterwards from Birmingham, to his sister-in-law and daughter respectively, he mentions in one "At Chester we read in a snowstorm and a fall of ice. I think it was the worst weather I ever saw. Nevertheless the people were enthusiastic."

And in the other, "It was the most tremendous night I ever saw at Chester."

A series of articles entitled In Our Own Country was published by Cassell & Co in serial form around 1879. One of them, by an anonymous author, dealt with Chester: A series of articles entitled In Our Own Country was published by Cassell & Co in serial form around 1879. One of them, by an anonymous author, dealt with Chester:

"There are very few towns where the enceinte of the walls is tolerably perfect- as at Conway and at York; so far as we know there is only one where it is possible to make the entire circuit without descending, and this is Chester.

This city also, as a whole, notwithstanding the many changes it has undergone in the last thirty years, preserves, better perhaps than any other in England, its connection with the past. It is the English Nuremberg, in some respects even more unique than that wonderful city, though its streets are less picturesque.

It has certainly the advantage in situation. This, without being exceptionally beautiful, is far finer than that of the old German town on the sandy plain by the side of the hardly less sandy Pilnitz.

But we must turn from the Chester of the remote past to the Chester of the present day. That, too, like so many of our English towns, has greatly changed during the reign of our Queen; and though still retaining, as we have said, the aspect of an old town, is rapidly becoming modernised, more convenient, and perhaps more healthy, but sadly less picturesque.

Of course, like everything else, the Rows have shared in the general smartening up of the town during the last forty years, and have lost a good deal of their rugged quaintness, and singularly picturesque aspect; but they are religiously preserved in plan, though often much altered in detail. Still, here and there, parts remain almost exactly as they must have been when the seventeenth century began.

The old houses are gradually disappearing, but Chester is still exceptionally rich in those picturesque structures, of timber and brick-work, which are especially characteristic of the western counties of England.

But it is time to leave the ancient city- a thing never easy for those who find a charm in memorials of the past;- and probably most travellers will agree with the latter part of a remark made once by Dr. Johnson to a lady: 'I have come to Chester, madam, I cannot tell how, and far less can I tell how to get away from it.’ "

Dr Oliver Wendell Holmes was an American physician and professor who also achieved fame as a writer. During his lifetime, he was one of the best regarded poets of the 19th century and is considered a member of the Fireside Poets. He made a tour of Europe in 1886-7 during which he visited Chester. His memories of the trip, One Hundreds Days in Europe, included the following... Dr Oliver Wendell Holmes was an American physician and professor who also achieved fame as a writer. During his lifetime, he was one of the best regarded poets of the 19th century and is considered a member of the Fireside Poets. He made a tour of Europe in 1886-7 during which he visited Chester. His memories of the trip, One Hundreds Days in Europe, included the following...

"Americans know Chester better than most other old towns in England because they so frequently stop there on their way from Liverpool to London. It has a mouldy old Cathedral, an old wall partly Roman, and strange old houses with overhanging upper floors, which make sheltered sidewalks and dark basements. When one sees an old house in New England with the second floor projecting a foot or two beyond the wall of the ground floor, country boys will tell him that "them haouses was built so th't folks upstairs could shoot Injins when they was tryin' to get threew th' door or int' th' winder". There are plenty of such houses all over England, where there are no "Injins" to shoot....

The walk round the old wall of Chester is wonderfully interesting and beautiful. At one part it overlooks a wide level field, over which the annual races are run. I noticed that here, as elsewhere, the short grass was starred with daisies. They are not considered in place in a well-kept lawn. But remembering the Cuckoo Song in Love's Labour's Lost, "When daisies pied.. do paint the meadows with delight". It was hard to look at them as unwelcome intruders.

The old Cathedral seemed to me particularly mouldy, and in fact too high-flavoured with antiquity. I could not help comparing some of the ancient cathedrals and abbey churches to so many old cheeses. They have a tough grey rind and a rich interior, which find food and lodging for numerous tenants who live and die under their shelter and shadow- lonely servitors, some of them portly dignitaries and others humble holy ministers of religion, many, I doubt not, larvae of angels who will get their wings by and by. It is a shame to carry the comparison so far but it is natural enough; for Cheshire cheeses are among the first things we think of as we enter that section of the country and this venerable Cathedral is the first that greets the eyes of great numbers of Americans".

Holmes went on the describe and reflect upon what he saw at the Grosvenor's seat of Eaton Hall. he considered "the vast marble palace... disheartening and uninviting" but was most interested in the stables and horses...

The following lengthy and rather romantic recounting of a European tour ending in a vist to Chester was penned by an anonymous correspondent to the New York Times and was published by that paper on 26th June 1881... The following lengthy and rather romantic recounting of a European tour ending in a vist to Chester was penned by an anonymous correspondent to the New York Times and was published by that paper on 26th June 1881...

"After Montenegro, the Channel Islands; after the Channel Islands, Devonshire; after Devonshire, Chester. All four are alike antique, but each in a way peculiar to itself. Montenegro is the antiquity of war; the Channel Isles that of sea-faring; Devonshire, that of country life; Chester, that of town life, and of town life in its most picturesque form, viz. that strange intermingling of romance and excitement with quiet jog-trot money-making, of savage bloodshed with hearty boyish merry-making, which gave such wonderful life and coloring to the world of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Sauntering along the "Rows", those quaint old street arcades which stand out like antique book-shelves over the trim modern sidewalk below, you find yourself amid the black-and-white crossbeams, the narrow loophole-like windows, the high-peaked roofs, the deep shadowy doorways, the projecting house fronts covered with strange antique carvings of the England of Edward IV. Everything that you see callls up a vision of portly burgesses with furred mantles and heavy gold chains, of buxom dames in coif and farthingale, of sturdy young 'prentices in their flat caps and grey jerkins, peeping slyly under the broad-leaved hats that shade thefresh, rosy faces of their master's pretty daughters.

But other and widely different associations are suggested by the huge dark wall which, rising gauntly up in the midst of the clustering houses, marks the limit of Chester as it was in the days when it formed the outwork of England against the still-foreign and hostile Kingdom of Wales. In that rough-hewn age, the life of a Chester draper or grocer was something more than a mere haggling over goods and summing up accounts. Any dark night, the beacon in the iron grate upon the highest tower might fling its warning glare upon the white mantles of Welsh warriors swarming through Moilvanna Pass, or the steel-capped retainers of some robber-baron of the Marches, who had cast a longing eye upon the well-filled warehouses and apple-cheeked damsels of the town. In an instant the quaint old streets would be filled with hurrying figures; the great bell would be clanging out its note of alarm; the walls would echo with the tramp of iron heels; every stout burgher would snatch down sword and buckler from the wall and hasten forth to the place of muster. And then, for two or three fierce hours to come, the glimmering moon and the flaring beacon would look down upon cut and thrust, slash and stab, shouts, groans, yells, wild faces, tossing arms, gleaming steel, armed masses swaying to and fro like contending tides. Then suddenly the hideous uproar would die away, the streets would be cleared of the slain and wounded, and the survivors of the fray would be found next morning busied among their wares and their ledgers as if nothing had happened.

One may almost say that the history of Chester is epitomized in the view afforded by the circuit of its walls. From the top of the old Water Gate you see a train steaming over a long viaduct towards those purple mountains from which Gryffyth and Blethwallon once poured their invading hosts. A little further on you look down upon the smooth, green surface of the famous "Rood-eye" over which Scott's doughty Constable of Chester careered with levelled lance in days when Chester races were still undreamed of, and when modern civilisation had not yet changed the tourney-field into a place for rogues to win money and fools to lose it. Around the further edge of the Rood-eye curves the bend of a broad, smooth shining river, no other than the Dee, upon which (possibly not far from this very spot) lived the "jolly miller" who has been immortalised by that jovial boast which "bluff King Hal" is said to have contradicted so emphatically:

"I envy nobody, no, not I

And nobody envies me!"

Just at this point appears a contrast equal to that celebrated by Burns in the "Auld and New Brigge of Ayr". Beyond the race-course the broad white highway, leading southward to Wrexham and the Welsh border, is carried across the Dee, at a considerable height above it, by one magnificent arch of hewn stone, with a span of fully 250 feet. To the left of this, about a quarter of a mile further up the river, its clear, bright current is flecked with a long streak of dark red, like a bar-sinister athwart some gorgeous escutcheon. This is the Old Bridge, with its low, massive, moss-grown arches of stern red sandstone contrasting strikingly with the green, sunny freshness of the level banks. Just beyond the bridge, a group of queer little toy houses, built on the wall itself, look down upon the river, which at this point almost touches the base of the rampart. On the left hand, a little higher up the slope, stands a grim old church of the Saxon style, the crumbling red tower of which is coeval with the city itself, and memorable to the curious in legendary lore froma weird old tradition of a tall, one-eyed, silent monk who lived there for many a year after the battle of Hastings, and whose name among men had been Harold, King of England.

Above this relic of the past stands another, which needs no aid of romance to adorn its associations. On the highest point of the ridge cluster the dark towers of the old castle, now garrisoned by English Red-coats and English cannon, instead of Norman men-at-arms with cross-bows and mamongel. Here ruled the grim Earl Leofric, husband of Tennyson's Godiva, and father of that Hereward whom the old chroniclers call "the last of the English" as having stood his ground against the Normans for more than a year after every other spark of Saxon independence had been trampled out by the iron heel of William the Conqueror. Here William himself established his headquarters during that wonderful campaign that overthrew the Saxon Earl Edwin and his Welsh ally Blethwallon, and carried fire and sword for many a league through the passes of the Welsh mountains. Here Edward I held high festival on his way to extinguish Cymrian nationality forever, and proclaimed his infant son, Edward II, born at Carnarvon Castle, as the first "Prince of Wales". And here- a strange association of ideas indeed- lived Matthew Henry, the famous biblical commentator, in whos honour a monumental tablet now stands in front of one of the principal churches. Above this relic of the past stands another, which needs no aid of romance to adorn its associations. On the highest point of the ridge cluster the dark towers of the old castle, now garrisoned by English Red-coats and English cannon, instead of Norman men-at-arms with cross-bows and mamongel. Here ruled the grim Earl Leofric, husband of Tennyson's Godiva, and father of that Hereward whom the old chroniclers call "the last of the English" as having stood his ground against the Normans for more than a year after every other spark of Saxon independence had been trampled out by the iron heel of William the Conqueror. Here William himself established his headquarters during that wonderful campaign that overthrew the Saxon Earl Edwin and his Welsh ally Blethwallon, and carried fire and sword for many a league through the passes of the Welsh mountains. Here Edward I held high festival on his way to extinguish Cymrian nationality forever, and proclaimed his infant son, Edward II, born at Carnarvon Castle, as the first "Prince of Wales". And here- a strange association of ideas indeed- lived Matthew Henry, the famous biblical commentator, in whos honour a monumental tablet now stands in front of one of the principal churches.

And now the wall bends round to the north east, and you pass through another cluster of those queer little houses that cling to its top like limpets every here and there. Most of them are small shops, and in not a few of their windows you see displayed a tempting muster of those quaint, worm-eaten, tobacco-colored folios and quartos for which Chester is famous, with red and black letters intermingled in their title-pages, like a half-finished game of chess.

All at once you find yourself looking over the balustrade of a solid arch down into the long vista of Foregate-street, the strangest imaginable jumble of ancient and modern, of Dutch tiles and hewn-stone fronts, carved porches and varnished doors, little bow-windowed taverns and tall, prim-looking hotels, oaken crossbeams and ornamental cornices. In the midst of this medly eddies a noisy flood of tall, sturdy, ruddy men in top-boots, and shoert, close-cropped men with sleek, shining faces, evidently engaged in some keen trial of commercial fence, while ever and anon the crownd is cleft by a bare-headed man on a vicious-looking horse, which he seems bent upon showing off to the best advantage; for there is no shrewder bargainer than your genuine North of England man when chaffering over the animal which his Danish forefathers used to eat. But there is no time to linger over the scene, life-like though it is; for now the wall makes another bend, and, passing through a serried mass of roofs and chimneys, brings you out suddenly in front of a small patch of smooth green turf, in the midst of which rises the stern, dark-red vastness of the ancient cathedral. The great central tower, huge, square, massive, rising far above the trim modern buildings around, fills the eye so royally that one almost regrets that the Shah did not see it before his celebrated introduction to the Duchess of Westminster, on which occasion his Majesty was graciously pleased to observe, "Ah, yes! I've heard of you, but I thought somehow that you were a good deal bigger"- having, in fact, mistaken her for Westminster Abbey.

And now comes the most picturesque part of the whole circuit. Just at the angle that faces towards the great railway depot, the wall is surmounted by a crumbling round tower, on the rusty, iron-studded door of which and inscription tells how Charles I stood here one grey September evening in 1645, and saw his last army smitten hip and thigh on Rowton Moor by the hard-handed saints of Cromwell. Beyond this tower, the rock upon which the wall is built goes sheer down into a deep, narrow, moat-like canal, on the other side of which lies a region of smoke and dust and red-brick chimneys, peopled with hard, sallow faces and bare, grimy arms and tattered blue shirts and uncouth, provincial patois and round-mouthed British oaths. This, slightly relieved at intervals by a dainty little garden or a patch of inclosed ground, brings you round again to your starting-point at the old Water-gate, and then, if you are wise, you will walk up Water gate-street itself and look at the quaintly-carved black and white front of an old and fast-decaying house halfway along it, upon one of the frontal beams of which are engraved, in crabbed, antique characters, the words "God's Providence is Mine Inheritance"- a memento, as every man, woman or child in Chester will tell you in a moment, of the gallant burgher who, when the shadow of the plague hung black over the doomed town, stood firm at his post with death staring him in the face, and escaped unharmed, while all around him there was not a house where there was not at least one dead.

This survey being over, the only thing left to do is to inspect the half-completed restoration of the cathedral, a task which could have fallen into no abler hands than those of good old Dean Howson, whose kindly face is a living contradiction to the popular theory of "dry-as-dust scholars", although his share in the "Conybeare and Howson" New Testament would suffice of itself to establish his reputation for learning. It is true that the cathedral work is still very far from completion. Nearly $500,000 has been expended upon it already, and as much more will probably be required to finish it. Still, much has undoubtedly been done. The taste and energy of the Dean have removed the hideous coating of plaster with which one of the finest interiors in Europe was defaced in the seventeenth century. Several huge, ungainly chandeliers and tasteless attempts at ornamentation have been wisely banished to a remote corner of the building. The unsightly partitions which once marred the symmetry of the transepts have been demolished, a reform which brought to light one curious relic of the past in the shape of a newspaper of the last century, which was found pasted upon one of the planks.

But one loses all thought of details in the first glance at the noble vista of the interior. So might some gerand old primeval forest appear if turned to stone, the stately trunks being represented by the solid strength of the pillared arches, and the clustering foliage by the sombre beauty of the panelling which hangs over them in mid-air. What a place for a midnight vigil on All Soul's Eve, when the ghostly moonlight, streaming through the great clerestory overhead, might reveal the cowled figures of pale, hollow-eyed monks gliding with noisless tread along the triforium, while the grim Norman warriors, starting up from the vaulted recesses below, flashed back the dim light of the altar candles from their battle-dinted mail. But one loses all thought of details in the first glance at the noble vista of the interior. So might some gerand old primeval forest appear if turned to stone, the stately trunks being represented by the solid strength of the pillared arches, and the clustering foliage by the sombre beauty of the panelling which hangs over them in mid-air. What a place for a midnight vigil on All Soul's Eve, when the ghostly moonlight, streaming through the great clerestory overhead, might reveal the cowled figures of pale, hollow-eyed monks gliding with noisless tread along the triforium, while the grim Norman warriors, starting up from the vaulted recesses below, flashed back the dim light of the altar candles from their battle-dinted mail.

But when once you have fully drank in the magnificent effect of the tableau as a whole, the details begin to grow on you little by little. If you do not duly appreciate them, it is no fault of the chatty old verger, who descants upon the improvements as fluently and complacently as if he had done the whole thing himself. It would have been a rare treat for Dickens to have jotted down the old fellow's quaint, rambling talk, with its high-flown guide-book phraseology, relieved ever and anon by architectural blunders almost as startling as that of the luckless schoolboy who stated that Cleopatra was "stung to death by an apse". Moreover, this good verger is a bit of a wag in his way, and keeps on hand a stock of mild little cathedral-precinct jokes, which season his discourse, not unpleasantly. "You will remark", says he, "the helegance of this wood-work, which is composed of oak from Bashan, cedar from Lebanon, and olive from Gethsemane. You don't see a mo-saic every day made of stone from Solomon's Temple; do you now, Sir? But such is actually the case with this mo-saic before the haltar, a gift from the Jerusalem excavators. You will next hobserve the tasteful design of the haltar-cloth, which, as you perceive, represents the seven plants symbolical of our Lord's Passion. The wheat and vine typify the sacrament, the flower and fruit of the olive the agony in the garden, the hyssop gave Him drink on the cross, and the flax and myrrh emblematise his burial. These oaken seats in the stalls, you notice, are made so as to slide off any monk who fell asleep- would come rather hard upon some modern congregations eh, Sir?

Here," he adds, turning up the seats and displaying various grotesque carvings of quarreling couples, mitred foxes, clergymen seizing tithe-pigs, and other samples of medieval wit; "here's a little 'igh art combined with moral teaching. This door used to lead into the confessional; it's a pretty wide one, as you see, no doubt to accomodate some Father Tichborne of those days. In this little room here we keep some of our curiosities, including, you perceive, a manuscript Bible of the twelfth century, and the remains of a black-letter Testament of the fifteenth, still retaining the chains which used to bind it to the front of the pulpit. This way out, Sir, if you please, and allow me to point out to you those two carvings on the wall. This, you see, represents Lord Beaconsfield defending the English Crown against Dr. Kenealy, and that is Mr. Gladstone overturning the Pope's triple crown with a lever. That's what one might call " truth disguised in a jest", as my old master, Canon A. said when he admonished his choir by changing the Litany to 'have mercy upon us, miserable singers'. Thank'ee Sir, and good day".

On we go to hear from some 20th Century visitors to Chester... |

The ramparts of Chester constitute the sole model still existing in England of the old mode of fortification. It is a high wall, wide enough for two persons to walk abreast, and runs round the whole town. Built during the middle ages, this wall rests on the foundations of an older one constructed by the Romans. You may still see, at more than one spot, the base of the Roman erection which served as the root of the modern works. Thus enclosed in a corset of red sandstone, the city could neither extend nor grow larger. The ramparts of Chester form an agreeble promenade, probably unique in the world: these fortifications, cut in the rock and raised to destroy the life of man, now serve to prolong it, for convalescents, old persons, and delicate ladies come here to breathe the pure air and enjoy the freshness of the scenery.

The ramparts of Chester constitute the sole model still existing in England of the old mode of fortification. It is a high wall, wide enough for two persons to walk abreast, and runs round the whole town. Built during the middle ages, this wall rests on the foundations of an older one constructed by the Romans. You may still see, at more than one spot, the base of the Roman erection which served as the root of the modern works. Thus enclosed in a corset of red sandstone, the city could neither extend nor grow larger. The ramparts of Chester form an agreeble promenade, probably unique in the world: these fortifications, cut in the rock and raised to destroy the life of man, now serve to prolong it, for convalescents, old persons, and delicate ladies come here to breathe the pure air and enjoy the freshness of the scenery.  On this city wall I met a man of about fifty, who was contemplating with thoughtful eye the solemnities of nature and the past. He was an ex parish clerk, compelled to resign his office owing to a disease which had weakened his eyesight; he was not a professional antiquarian, and yet it was easy to recognise in his language a sincere and assiduous admirer of the venerable relics of history. According to him, there was only Chester in the world, and I confess that momentarily I shared his enthusiasm. Though poor and meanly clad, he was an optimist: at the sight of the old memorials which recalled recollections of feudalism, the bloody wars of religion, and the times of ignorance, he burst into ecstasies at the happiness of living in an enlightened age. I have no liking for ciceroni, but this man was not a professional one. "I am," he told me, " a native of the city. Formerly I spent my leisure hours in studying old histories of Chester, but now I have bad eyesight, and this walk is my book, and I find here, written in legible characters, the happy changes which time has introduced into human institutions. That old tower you see down there is

On this city wall I met a man of about fifty, who was contemplating with thoughtful eye the solemnities of nature and the past. He was an ex parish clerk, compelled to resign his office owing to a disease which had weakened his eyesight; he was not a professional antiquarian, and yet it was easy to recognise in his language a sincere and assiduous admirer of the venerable relics of history. According to him, there was only Chester in the world, and I confess that momentarily I shared his enthusiasm. Though poor and meanly clad, he was an optimist: at the sight of the old memorials which recalled recollections of feudalism, the bloody wars of religion, and the times of ignorance, he burst into ecstasies at the happiness of living in an enlightened age. I have no liking for ciceroni, but this man was not a professional one. "I am," he told me, " a native of the city. Formerly I spent my leisure hours in studying old histories of Chester, but now I have bad eyesight, and this walk is my book, and I find here, written in legible characters, the happy changes which time has introduced into human institutions. That old tower you see down there is  "Formerly the inhabitants of Chester were distinguished for a very lively taste for dramatic representations: it may even be said that our city was the cradle of the English stage. Another source of amusement that attracted a great many strangers was the fair, and it was a custom during this fair that a glove should be hung up in the town hall and afterwards on the roof of St. Peter's church. To understand the meaning of this emblem, you must know that Chester was celebrated for centuries for its manufacture of gloves, and that in the time I speak of trade was not free; the right of carrying on any traffic was a privilege reserved solely for citizens born within the city. During the fair, on the contrary, everybody might set up as a trader, and the glove hung up was the signal that proclaimed the temporary liberty. The custom had lasted for centuries, when the Reform Bill, that just and obstinate foe of ancient monopolies, extended the rights throughout the whole year to all strangers and townsmen. The authorities of the city still continued for some time to hang up the old banner outside the wall. I have myself seen this public ceremony- a reminiscence of another age- and it is only during the last twenty years that the custom has been abolished."

"Formerly the inhabitants of Chester were distinguished for a very lively taste for dramatic representations: it may even be said that our city was the cradle of the English stage. Another source of amusement that attracted a great many strangers was the fair, and it was a custom during this fair that a glove should be hung up in the town hall and afterwards on the roof of St. Peter's church. To understand the meaning of this emblem, you must know that Chester was celebrated for centuries for its manufacture of gloves, and that in the time I speak of trade was not free; the right of carrying on any traffic was a privilege reserved solely for citizens born within the city. During the fair, on the contrary, everybody might set up as a trader, and the glove hung up was the signal that proclaimed the temporary liberty. The custom had lasted for centuries, when the Reform Bill, that just and obstinate foe of ancient monopolies, extended the rights throughout the whole year to all strangers and townsmen. The authorities of the city still continued for some time to hang up the old banner outside the wall. I have myself seen this public ceremony- a reminiscence of another age- and it is only during the last twenty years that the custom has been abolished." Though the majority of the houses is built of brick or wood, the relations of geology with the architecture of towns may be specially studied at Chester. All the old edifices are built of new red sandstone, and the most admirable of all are the

Though the majority of the houses is built of brick or wood, the relations of geology with the architecture of towns may be specially studied at Chester. All the old edifices are built of new red sandstone, and the most admirable of all are the

Keenly interested in the sciences and in cultural activities, he decided to raise money for the City Library by starting evening classes in botany. Advertised at 3d for the evening, the idea attracted 40 young people of both sexes. The presence of women, however, alarmed Kingsley. Although he had in the past supported women's rights, he did not favour the idea that both sexes should learn together. As he said: "The presence of young ladies might prove too strong a counter attraction. Let Mr John Price take the ladies. He is the nicest man and should have the nicest pupils."

Keenly interested in the sciences and in cultural activities, he decided to raise money for the City Library by starting evening classes in botany. Advertised at 3d for the evening, the idea attracted 40 young people of both sexes. The presence of women, however, alarmed Kingsley. Although he had in the past supported women's rights, he did not favour the idea that both sexes should learn together. As he said: "The presence of young ladies might prove too strong a counter attraction. Let Mr John Price take the ladies. He is the nicest man and should have the nicest pupils."