|

pproaching

the

end

of

Nun's

Road on

the

western

section

of

Chester's

city

walls,

we

see

below

us

the

numerous

and

complex

rooftops

of

the

various

buildings

connected

with

the

Racecourse

on

the Roodee. pproaching

the

end

of

Nun's

Road on

the

western

section

of

Chester's

city

walls,

we

see

below

us

the

numerous

and

complex

rooftops

of

the

various

buildings

connected

with

the

Racecourse

on

the Roodee.

The

road

before

us

dips

down

sharply

to

the

traffic

lights

and

busy

junction

with Watergate

Street (take

care

here)-

but

the

wall

rises

slightly

to

lead

us

on

to

the Watergate.

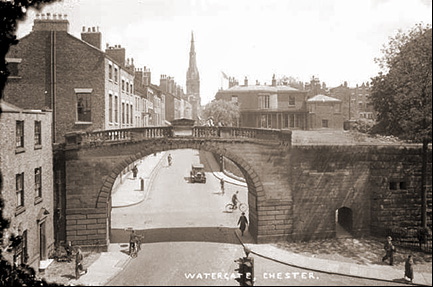

On

the

right

we

see

the

gate

as

it

appeared

in

1888,

in

one

Francis

Frith's

fine

views, and below in a postcard from 1940.

Except

that

the

fancy gas

lamp

atop

the

gate

in the earlier picture has

been

removed-

and

an

inevitable

huge increase

in

traffic-

this

scene

is

little

changed

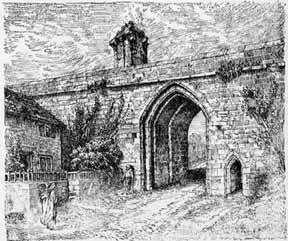

today. Compare it with the conjectural artist's impression of how the original Watergate looked, below..

As

with

the

city

gates

previously

visited

on

our

walk,

this

is

another

example

of

an

18th

century

arch

built

to

replace

a fortified

medieval

gateway.

At

the

time

of

its

purchase

by

the

corporation

from

the

Earl

of

Derby

in

1788,

it

was

considered

so "dangerously

ruinous" that

it

had

to

be

immediately

demolished

and

the

present

arch,

designed

by Joseph

Turner,

was

erected

the

following

year.

Turner

also

designed

the Bridgegate and

the

elegant

row

of

houses

in

Nicolas

Street, known, because of the number of doctors who lived and practised there,

as 'Pill-Box

Terrace'-

which

we

will

visit

shortly. His home was in nearby Paradise Row, of which more below...

On

the

western

front

of

the

Watergate

may be seen

the following

inscription: On

the

western

front

of

the

Watergate

may be seen

the following

inscription:

IN

THE

XXIX.

YEAR

OF

THE

REIGN

OF

GEO.

III

IN

THE

MAYORALITY

OF

JOHN

HALLWOOD

AND

JOHN

LEIGH,

ESQUIRES,

THIS

GATE

WAS

ERECTED-

THOMAS

COTGREAVE,

EDWARD

BURROWS,

ESQUIRES,

MURENGERS.

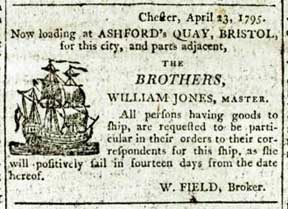

The Watergate was closely guarded until well into the 18th century, and had been ably protected

by a heavy double door, portcullis and drawbridge.

Tolls were levied on all

goods entering the town, not just here but at all of the city's gates, a portion of which were taken as murage, a tax to fund the maintainance of the defences, carried but by an order of masons by the name of the Murengers. What remained went into the ample pockets of the noble families who paid huge sums to the King for the right to collect the dues. Due to its proximity to the busy harbour, the Sergeancy of the Watergate had long

been regarded as a coveted and lucrative position and was held by the Stanleys,

Earls of Derby, whose fine, black & white timber town house, Stanley Palace (1591)

still stands, a little way up the hill, on the right hand side of Watergate Street.

Their employee, the Keeper of the Watergate, to quote the ancient records, "takes of every cart entering with firewood: one branch; of every horseload

of fish: five fishes; of every boat coming to the aforesaid gate with large

fish or salt salmon: one fish; with herring, fifty".

In 1615, referring to the status of the Watergate and its neighbourhood, it

was said "which gate is less than any of the other three, serving only for

the passage to the rood-eye and to the banks of the river, where are brought

into the city all such commodities of coal, fish, corn and other things; which

barks and other small vessels bring up so far upon the waters of Dee". In 1615, referring to the status of the Watergate and its neighbourhood, it

was said "which gate is less than any of the other three, serving only for

the passage to the rood-eye and to the banks of the river, where are brought

into the city all such commodities of coal, fish, corn and other things; which

barks and other small vessels bring up so far upon the waters of Dee".

We regret to say that visitors walking our City Walls today will observe that the Watergate is rather a sorry sight. It remains passable but is covered in scaffolding and has, remarkably, remained in this condition since as long ago as September 2012. Remedial work had been carried out a few years before this but evidently proved to be less than satisfactory and the current distressing situation is the result. It remains a mystery to caring locals as to why there has been such a long delay in carrying out the necessary repairs; responsibility for maintaining Chester's historic infrastructure falls to Cheshire West and Chester Council, advised by English Heritage, but they say there is no money to address the problems, not just here but also at the Northgate, Abbey Green and the City Walls adjoining the Groves among others. Meanwhile, half a million pounds has been found to restore Chester's best known entrance, the Eastgate and its famous clock- for the third time in the last quarter century. Watch this space for news of future improvements..

Beyond the Watergate

Looking

out

here

from

the

City Walls,

beyond

the

nearby Watergate

Inn and

main

entrance

to Chester

Racecourse,

the

modern view

of

busy New

Crane

Street,

with

a large

car

park

to

its

right, is

fairly

uninspiring.

Consider, however, that where we stand was for centuries

the

main

gateway

to

the

wharves

and

quays

of

the largest, most important seaport in the region and

ancient

Watergate

Street

once

its

'dock

road'.

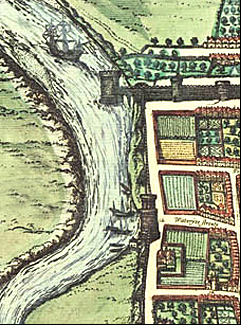

16th

and

17th

century maps, such as that by Braun here (see the whole of his impressive 1571 map of the city, and many more, here) - show

the

River

Dee

approaching

right up

to

the

Watergate,

allowing

just

enough

room

for

a quay

where

goods

were

loaded

and

unloaded

to and from

waiting

ships

and

from where heavily laden carts and trains of pack horses laboured up the hill, carrying the goods via the Customs House to the safety of the merchant's houses in the town. 16th

and

17th

century maps, such as that by Braun here (see the whole of his impressive 1571 map of the city, and many more, here) - show

the

River

Dee

approaching

right up

to

the

Watergate,

allowing

just

enough

room

for

a quay

where

goods

were

loaded

and

unloaded

to and from

waiting

ships

and

from where heavily laden carts and trains of pack horses laboured up the hill, carrying the goods via the Customs House to the safety of the merchant's houses in the town.

Later,

as

the

River

Dee silted

and

receded and, followed the canalization of the lower river in the first half of the eighteenth century, new quays

and

shipyards

were

established along the newly aligned riverbank standing further out from the Watergate in the area we still call today 'The Old Port'.

In accordance with the scheme of development the site of the old wharf immediately outside the Water Gate was levelled, and an open space, then and now called Watergate Square, was formed. From this point three new roads, Paradise Row, Middle Crane Street, and New Crane Street, were laid out to give access to various parts of the riverside. Subsequently, one or two minor cross streets and a number of courts came into being. All of these streets were constructed after 1745, when the only way between the Water Gate and the wharves was an indirect track alongside and across an extensive timber yard that then occupied much of the later residential area. This track started at the Watergate and, after following a part of the course of what is now New Crane Street, passed through the middle of the timber yard and reached the Old Crane along the lower end of what became Middle Crane Street.

The houses that soon arose along these new thoroughfares were, doubtlessly in the first instance inhabited by people specially interested in the new port and its facilities, such as merchants, shipbuilders, mariners, customs officials, etc. As time went on and the temporary prosperity of the port declined, most of the original tenants gradually drifted away and their places were taken by others unconnected with the maritime affairs of Chester. These later inhabitants considered the area to be a convenient and not undesirable place of residence, and those who selected Paradise Row would appreciate the attractive outlook over the Roodee. It was described as "a

street

of

genteel

houses" according

to

the

1792

directory. Near here also existed in the eighteenth century a building known as 'The Pentice on the Roodee' at which, presumably, the business of the Corporation in connection with the port was dealt with.

The author of an anonymous work, A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, published around 1800, has this to say regarding the area, "On the north east side (of the Roodee) is Paradise Row, a street built within these few years; beyond that, Crane-street. By an ancient map, in the Editor's possession, the deepest part of the river, two centuries back, was formed in the centre of these streets and the channel flowed to the entrance of the Gate-way". The author of an anonymous work, A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, published around 1800, has this to say regarding the area, "On the north east side (of the Roodee) is Paradise Row, a street built within these few years; beyond that, Crane-street. By an ancient map, in the Editor's possession, the deepest part of the river, two centuries back, was formed in the centre of these streets and the channel flowed to the entrance of the Gate-way".

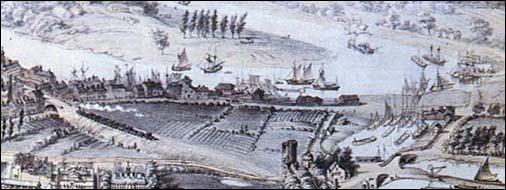

This aerial

view-

a

detail

from

John

McGahey's

famous View

of

Chester

from

a

Balloon- shows

the Old

Port and

its

surroundings

as

they

appeared

in 1855.

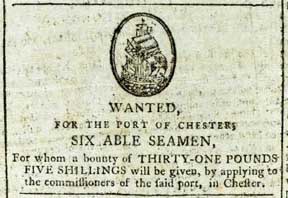

Despite the canalisation of the River Dee years earlier, it continued to silt up and the boom years of the commercial port were not to last. J. H. Hanshall, the second Editor of the Chester Chronicle (first published in 1775 and still around today), wrote, “As the years go by it is clear from the newspaper and other records that the trade of the Port of Chester is drifting desultorily but inexorably into the silting sand. But if the bigger ships of the day can no longer reach her, the history of former times repeating itself, the old Port can at least build ships for others".

He described the area as he saw it around 1816: "Beyond the Watergate are Crane-street, Back Crane-street, and Paradise Row, the whole of which lead to the wharfs on the river. For a number of years Chester has carried on a considerable business in shipbuilding. Within the last ten years the trade has wonderfully increased, and even now it is not unusual to see ten or a dozen vessels on the stocks at a time. In fact, there are nearly as many ships built in Chester as in Liverpool, and the former have always a decided preference from the merchants. Indeed, Chester lies particularly convenient for the trade, as by the approximation of the Dee, timber is every season floated down from the almost exhaustless woods of Wales, at a trifling expense and without the least risk. The principal shipwright in Chester is Mr. Cortney, but Mr. Troughton’s is the oldest establishment. There were lately nearly 250 hands employed in the business, two-thirds of whom were in Mr. Cortney's yard, but the trade is at present flat. Six vessels of war have been built by him, and within the last two years (1814-15) two corvettes and two sloops of war, The Cyrus, The Mersey, The Eden, and The Levant, from twenty to thirty guns each. The firm of Mulvey and Co., formerly of Frodsham, have established a yard near the Crane. Cortney's yard launched a brig in 1804, an East lndiaman of 580 tons in 1810, and in 1813 a West India-man of 800 tons, in addition to the corvettes and war sloops mentioned by Hanshall.”

Writing in The Cheshire Sheaf, one ‘J.H.E.B’ described the area as he knew it in June 1945, “Middle Crane Street. This street, originally known as Crane Street and later as Old Crane Street, was the first of the roads to be laid out. its course is in a direct line from the Watergate to the Old Crane, and its construction necessitated the removal of the large timber yard to a site immediately under the Walls to the north of the Watergate. It appears to have been constructed shortly after 1750 and certainly before 1782. A glance at the houses of Middle Crane Street indicates that those at the upper end, at least, were intended for occupation by people of some stability, and that they were built towards the close of the eighteenth century. Some of the houses on the south side of the street have gardens in the rear that extend as far as Paradise Row and thus afford an excellent view of the Races and other events held on the Roodee. Writing in The Cheshire Sheaf, one ‘J.H.E.B’ described the area as he knew it in June 1945, “Middle Crane Street. This street, originally known as Crane Street and later as Old Crane Street, was the first of the roads to be laid out. its course is in a direct line from the Watergate to the Old Crane, and its construction necessitated the removal of the large timber yard to a site immediately under the Walls to the north of the Watergate. It appears to have been constructed shortly after 1750 and certainly before 1782. A glance at the houses of Middle Crane Street indicates that those at the upper end, at least, were intended for occupation by people of some stability, and that they were built towards the close of the eighteenth century. Some of the houses on the south side of the street have gardens in the rear that extend as far as Paradise Row and thus afford an excellent view of the Races and other events held on the Roodee.

Paradise Row appears to have been constructed shortly after Middle Crane Street. It was in existence in 1782 and it provided a more direct access to the considerable works that stood on the site now occupied by the Gas Company. Paradise Row, flanked by its neat looking houses and lengths of garden walls, is a quiet highway except at the times of the annual races. Most of its present vehicular traffic is bound to or from the Gas Works, but in its early years it served timber yards, iron works, and part of the shipyards, as well as the Old Workhouse. Paradise Row appears to have been constructed shortly after Middle Crane Street. It was in existence in 1782 and it provided a more direct access to the considerable works that stood on the site now occupied by the Gas Company. Paradise Row, flanked by its neat looking houses and lengths of garden walls, is a quiet highway except at the times of the annual races. Most of its present vehicular traffic is bound to or from the Gas Works, but in its early years it served timber yards, iron works, and part of the shipyards, as well as the Old Workhouse.

It has had some notable residents, such as Joseph Turner, the architect who designed the Bridgegate and a number of other buildings in Cheshire, Denbighshire and Flintshire.

New Crane Street was made between 1782 and 1795 and as the name suggests, it provided direct access to the later but more enduring New Crane. With one or two exceptions the older buildings along its course are of a humbler character than those in the other streets.”

Earlier, Chester author and guide Joseph

Hemingway,

writing

in

1836,

stated

that "the

river

here is

navigable

for

ships

of

350

tons

burthen.

From

the

quays

are

exported

some

of

the

richest

cargoes

of

that

excellent

commodity

which

affords

to

the

taste

of

the

Londoners

the

most

grateful

flavour,

and

presents

the

Cockney

with

what

he

calls

"The

fattest

Velsh

rabbits

in

the

Vorld"-

good

old Cheshire

Cheese.."

To

the

left,

between

here

and

the

Roodee,

stood

150

years

ago

the previously-mentioned workhouse or House

of

Industry asit was called at the time.

Hemingway

again: "That

asylum

for

age

and

indigence,

whose

inmates

are

provided

with

all

necessities

of

food

and

clothing;

it

is

regularly

visited

by

a clergyman

and

a medical

man,

and

contains

a school

and

an

establishment

for

insane

paupers".

The author of A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester wrote of it in 1800, "on the west side of the Rood-eye stands the general Work-house, or House of Industry, where the poor of the several parishes are employed, and provided for in a proper manner. It is a commodious building and contains generally two hundred persons. It receives the poor from distant parishes, by agreement between the governor and parish officers." The author of A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester wrote of it in 1800, "on the west side of the Rood-eye stands the general Work-house, or House of Industry, where the poor of the several parishes are employed, and provided for in a proper manner. It is a commodious building and contains generally two hundred persons. It receives the poor from distant parishes, by agreement between the governor and parish officers."

This

area,

today

known

as 'The Old

Port' (illustrated left as it was in the 19th century) a few years ago underwent

a major

redevelopment.

New

houses, apartments, young

people's

accomodation and other valuable facilities

were

built,

but

a plan

to

demolish

the

historic

Victorian Electric

Light

Building led

to

a spirited, two-year

campaign

of

opposition

from

local

people-

which

resulted

in

at

least

the

facade

of

this important

building

being

saved

and

incorporated

within

the

new

development. Read more about it in our chapters devoted to the Old Port area here.

Within

the

City

Wall, Watergate

Street rises

steeply

to

where

the

spire

of Holy

Trinity

Church-

also

known

as

The Guildhall-

stands,

near

to

which

was

the

West

Gate

of

the

Roman

Fortress-

the Porta

Principalis

Dextra-

and

from

that

point

lies

the

line

of

the Via

Principalis,

the

present-day

Watergate

and

Eastgate

Streets.

Could

the

Saxon

founders

of

Holy

Trinity

have

ulitised

a

ruined

gatehouse

connected

with

the

West

Gate

for

their

first

church?

A

very

similar

situation

existed

in

what

is

now

the

middle

of

the

busy

junction

of

Bridge

Street

and Grosvenor

Street,

where

for

centuries

there

stood

a

church

dedicated

to St. Bridget,

which

was

founded

around

the

year

797

by

King

Offa

on

the

site

of

the

vanished

Roman

Southgate,

or Porta

Praetoria.

Another ancient church once existed in this part of Chester, one dedicated to St. Chad. One source stated that the church, "stood in the croft over against the Black Friars on the north side of Watergate Street near to the Watergate". A document of 1388 makes mention of a garden situated close to it, but other than that, we have virtually no further information about the church, or of when and why it disappeared. Its approximate site is today occupied by The Queen's School, which we will visit a little later in our walk around Chester's walls.

The Grey Friars

All of the land bounded by today's Watergate Street, Bedward Row (which we will pass just before we reach the Infirmary), St. Martin's Way (the Inner Ring Road) and the City Walls once formed the precinct of the Franciscan Friars- the Grey Friars. We learned a little of their neighbours, the Dominicans or Black Friars and the nuns of St. Mary's in our previous chapter. All of the land bounded by today's Watergate Street, Bedward Row (which we will pass just before we reach the Infirmary), St. Martin's Way (the Inner Ring Road) and the City Walls once formed the precinct of the Franciscan Friars- the Grey Friars. We learned a little of their neighbours, the Dominicans or Black Friars and the nuns of St. Mary's in our previous chapter.

The friary was founded in 1237-8, only a year or so after the Dominicans- who actually opposed their foundation on the grounds that they feared there would not be enough alms forthcoming in the small town to support both institutions.

Having overcome these early difficulties, for the three centuries of their existence the friars seem to have gone about their business uneventfully and history tells us little of them. The Franciscans were always the smallest and poorest of the religious foundations in Chester and indeed, by 1529, they had become so impoverished that they were compelled to let out the nave and three aisles of their church to the merchants and sailors of Chester, as a place for storing and repairing sails and other things requisite for their ships, on the understanding that the merchants undertook all necessary repairs to the church.

Together with the other two Chester religious houses on this side of the city, the unfortunate Franciscans finally surrendered their house to Henry VIII's commissioners on 15th August 1538 after which time the estate passed through the hands of several owners including, in 1588, the Warburtons. They sold it to the Stanleys,

Earls of Derby, in 1622 who retained the lands until 1775 when they were purchased by the Linen Merchants, who erected their new Linen Hall on part of the site and sold the rest for residential development. On this western half of the site arose during the 1770s Watergate Flags (the area immediately outside the Watergate), Stanley Place and Stanley Street. At the time of the sale the entire area was known as the Grey Friar's Close or, alternatively, as the Yacht Field. We will discuss this area further in our next chapter...

The friary buildings, remarkably, survived right through from the Dissolution until this final splitting up of the lands for development and the tall steeple of their church long served as a guide to mariners entering the Port of Chester, and is marked on contemporary charts as such, before falling into private hands and finally being demolished. The antiquarian William Webb wrote of its removal, "It was a great pitie that the steeple was put away, being a great ornament to the citie. This curious spire steeple might still have stood for grace to the citie had not private benefit, the devourer of antiquitie, pulled it down with the church, and erected a house which since hath been of little use, so that the citie lost so good an ornament, that tymes hereafter may talk of it, being the only seamark for direction over the bar of Chester".

Our city, it seems, has suffered from the destructive ways of the property developer for longer than we realised.

Aside from the nuns of St. Mary's, the Blackfriars and Greyfriars, whose houses all were situated on this side of the city, and the Benedictine monks of the great Abbey of St. Werburgh (now the Cathedral), there was yet another religious community in Chester- that of the Carmelite White Friars. Their monastery and lands were situated on the other side of Nicolas Street, the modern Inner Ring Road and the narrow street called White Friars (formerly White Friars Lane) perpetuates their name to this day. The monks acquired further parcels of land as time went by and their estate in its final form was bounded by Commonhall Street to the north, White Friars to the south, Bridge Street to the east and Weaver Street to the west.

Left: The view from the Watergate along Nun's Road with the Roodee and buildings of Chester Racecourse on the right. The former Greyfriars' lands are on the left.

Their community had existed in Chester since around 1277 but it was only in 1290 that one Hugh Payn granted

them land "in a suburb of Chester" on which to build their house. That this area, now very much in the heart of the city, was referred to as a 'suburb' indicates how undeveloped great areas within the Walls long remained and, indeed, this area did not finally become fully built-up until the late 15th century.

As with the other religious houses, the Carmelite's church was rebuilt and enlarged several times over the two and a half centuries of occupation and in 1495 the tower was rebuilt and furnished with a tall and graceful steeple.

When the Dissolution came in 1538, as with the other religious houses (except, of course, for the Abbey), the monks were dispossessed and the buildings and land passed through the hands of several owners, including the Duttons and Gamuls, who probably made their substantial mansion from the monk's former domestic quarters and buildings of the outer court. The large and impressive church, however, long remained in use- it may be seen on Braun's 1571 map of Chester- and became the burial place of several prominent local families. But, in 1592, it was sold to Thomas Egerton, the Attorney-General, who proceeded to tear down the church and spire, and possibly the other buildings as well, and built his mansion on the site. This in turn disappeared and was replaced by the large private house, 'The Friars', which remains, standing in its extensive grounds, with us today. When the Dissolution came in 1538, as with the other religious houses (except, of course, for the Abbey), the monks were dispossessed and the buildings and land passed through the hands of several owners, including the Duttons and Gamuls, who probably made their substantial mansion from the monk's former domestic quarters and buildings of the outer court. The large and impressive church, however, long remained in use- it may be seen on Braun's 1571 map of Chester- and became the burial place of several prominent local families. But, in 1592, it was sold to Thomas Egerton, the Attorney-General, who proceeded to tear down the church and spire, and possibly the other buildings as well, and built his mansion on the site. This in turn disappeared and was replaced by the large private house, 'The Friars', which remains, standing in its extensive grounds, with us today.

Of more recent times, the site of the old Greyfriar's monastery was occupied by a complex of utilitarian Government offices by the name of Norroy House. After these were vacated, they were extensively restored and enlarged to house a brand new hotel which opened for business in April 2015.

Back in Watergate Street, this

19th

century

engraving

shows

the ancient Yacht

Inn (named after the Yacht Field upon which it was built) and

the

view

up

Watergate

Street

towards

the

centre

of

the

city

and

The Cross. On

the

left, Holy

Trinity

Church is

yet

to

be

rebuilt

and

acquire

the

tall

spire

we

see

today-

which

work

was

carried

out

in

1865-9

by

James

Harrison.

As

we

stand

atop

the

Watergate,

the

late

18th

century

houses

nearest

to

us

on

the

north

side

of

the

street

occupy

the

site

of

the

legionary

bath

houses

which

were

situated

here

outside

the

fortress

to

minimise

fire

risk

and

be

nearer

to

the

water

source. As

we

stand

atop

the

Watergate,

the

late

18th

century

houses

nearest

to

us

on

the

north

side

of

the

street

occupy

the

site

of

the

legionary

bath

houses

which

were

situated

here

outside

the

fortress

to

minimise

fire

risk

and

be

nearer

to

the

water

source.

That

side

of

the

nearby

corner

house

which

runs

parallel

with

the

wall

still

has

as

its

foundation

part

of

the

west

wall

of

the

ancient

bath

house,

which

is

pierced

by

the

furnace

arch

of

a hypocaust.

Also

found

on

the

site

were

the

remains

of

a sudatory (sweating

bath)

and

many

tiles

stamped

with

the

wild

boar

motif

of

the

XXth

Legion,

considerable

amounts

of

coins

of

the

reigns

of

Hadrian

and

Trajan

and-

most

importantly-

a carved

altar, dedicated to 'Fortune the Home-bringer, to Aesculapius and to Salus'. One of the sculptures on the side of the altar is a staff entwined with a snake, the distinctive symbol of Aesculapius who was the greatest Greek and Roman healing god (a similar motif is still used today in medicine). Salus was the goddess of health. Another carving on the side is a rudder, symbol of life's course, which was set by the goddess Fortuna.

The altar was set up by the freedmen and slaves in the household of a Roman officer, perhaps because he was ill. This man, the extravagantly-named Titus Pomponius Mamilianus Rufus Antistianus Funisulanus Vettonianus, was the Legatus (Commander) of the 20th Legion at Chester, probably around the year AD 100. His unusually long name is similar to that of a friend of the younger Pliny, and they may be one and the same man, or near relatives..

Due to the lack of a suitable local exhibition place, the

altar

ended up

200

miles

away

in

the British

Museum in

London, where it remains on show today.

Such was the casual attitude to antiquities at the time that one Philip Egerton had a large number of hypocaust pillars and Roman tiles from the site taken to his country mansion at Oulton Park (now a famous motor racing venue) near the Cheshire village of Little Budworth, where they were formed into the floor of a mock 'Druid's Temple' he was having built on the estate.

Som e of the pilae didn't make it as far as Egerton's home and ended up instead in the surrounds of Oakmere Lake. Tragically,

all

other

traces

of

the

extensive

remains

found

on

the

site

were

swept

away- "destroyed

by

the

rude

hand

of

ignorance"-

when

the

present houses

were

built

in

1799.

The

corner

one,

as

we

shall

learn

later,

in

1878

became

the

original

home

of

the Queen's

School

for

Girls. e of the pilae didn't make it as far as Egerton's home and ended up instead in the surrounds of Oakmere Lake. Tragically,

all

other

traces

of

the

extensive

remains

found

on

the

site

were

swept

away- "destroyed

by

the

rude

hand

of

ignorance"-

when

the

present houses

were

built

in

1799.

The

corner

one,

as

we

shall

learn

later,

in

1878

became

the

original

home

of

the Queen's

School

for

Girls.

That

'rude

hand

of

ignorance'

is

a

phenomenon

by

no

means

restricted

to

times

long

gone.

An

even

larger,

and

far

better

preserved,

Legionary

bath

house- "Extending

for

almost

200

feet

with

walls

standing

up

to

12

feet

or

more

in

height"-

found

during

the

construction

of

the Grosvenor

Precinct was

swept

away

for

the

construction

of

underground

delivery

bays,

a

mere

thirty

years

ago.

The

author

recently

photographed

the

well-preserved

remains

of

a

small

Roman

civil

bath

house

in Prestatyn -

a

small

seaside

resort

a

few

miles

along

the

North

Wales

coast,

and

not

otherwise

noted

for

its

antiquities.

Still

clearly

visible

in

situ

are

tiles

stamped

'Leg

XX

VV'

and

bearing

the

wild

boar

motif,

probably

made

at

the

Legionary

works

depot

at Holt on

the

River

Dee.

Shamefully,

Chester,

the

great

fortress

of Deva,

can

boast

of

nothing

like

this

outside

of

sorry

remnants

in

the

glass

cases

of

the

Grosvenor

Museum.

There

was

a

time

when

destruction

came

to

Watergate

Street

in

more

violent

ways. Randle

Holme III wrote

of

the

bursting

of

some grenados (mortars)

here

on

December

10th

1645,

during

the

Civil

War Siege

of

Chester, "Two

houses

in

the

Watergate

Street

skip

joint

from

joint,

and

create

an

earthquake;

the

main

posts

jostle

each

other,

while

the

frightened

casements

fly

for

fear,

in

a

word,

the

whole

fabric

is

a

perfect

chaos,

lively

set

forth

in

the

metamorphosis:

the

grandmother,

mother

and

three

children

are

struck

stocke

dead

and

buried

in

the

ruins

of

their

humble

edifice"...

Read more of Holmes' terse description of the great destruction caused to Chester during those troubled times here- or go on to part II of our exploration of the Watergate area...

Curiosities from Chester's History no. 23

-

1693

A

Roman

altar

found

in Eastgate

Street,

which

had

been

erected

by

Flavius

Longus,

military

Tribune

to

the

20th

Legion

and

his

Son,

Longinus

from

Samosata

in

honour

of

the

Emperors

Diocresian

and

Maximian

"in

discharge

of

a

vow

to

the

Genio

Loci". -

- 1695 The Exchange commenced (completed 1698). The forerunner of today's Town Hall, it stood in the Market Square until it burned down in 1862.

-

1696

New

coinage

in

England

carried

out

by John

Locke and Isaac

Newton (who up the post of Warden of the Royal Mint in this year) .

Chester

selected

as

one

of

six

cities

to

be

allocated

an

Assay

Office-

a

mint

being

this

year

set

up

and

coinage

of

money

(which

bore

a

'C'

under

the

monarch's

head)

began

on

the

2nd

October. Old hammered silver coins were recalled, melted down and re-issued as milled coins. In charge of the Chester mint was

the

great

astronomer Edmund

Halley-

he

of

comet

fame.

In 1697, he

observed

a

rare

triple

rainbow from the Phoenix Tower. -

1699

The Bluecoat

School outside

the Northgate was

founded

by

Bishop

Nicolas

Stratford.

The

'Recorder's

Steps'

by

the

river

were

built

as

a

compliment

to

Roger

Comberbach,

Recorder

of

Chester -

-

- 1702

William

III

died

and Queen

Anne (1665-1714) came

to

the

throne.

The

Quaker's

Meeting

House

in

Cow

Lane

(Frodsham

Street)

built,

and Pemberton's

Parlour was

rebuilt.

- 1704 The City Walls extensively repaired after their pounding during the Civil War and converted to promenades.

|