ere

is

the

view,

as

seen

on

a

snowy

day in January 2013, as

we

leave

the Northgate and

proceed

along

the

North

Wall

with

the

Shropshire

Union

Canal

running

far

below

us.

This

section

is,

in

my

view,

the

most

spectacular

and

evocative

of

the

entire ere

is

the

view,

as

seen

on

a

snowy

day in January 2013, as

we

leave

the Northgate and

proceed

along

the

North

Wall

with

the

Shropshire

Union

Canal

running

far

below

us.

This

section

is,

in

my

view,

the

most

spectacular

and

evocative

of

the

entire

This

is

the

the

most

elevated

section

of

the

walls

and,

even

on

hot

days,

there

is

usually

a

refreshing

breeze

blowing

from

the

Welsh

hills.

The

walkway

at

this

point

is

very

narrow-

not

a

good

place

to

meet

a

large

group

of

visitors

coming

the

other

way!

From 1991-2000, your

guide's

photography

studio and gallery, The Black & White

Picture

Place,

was, for a few years, located

in the newly-developed Rufus

Court. Built by the Thompson Cox Partnership and designed by James Brotherhood, Rufus Court and is

one

of

the

finest

examples

of

that

rare

thing

in

Chester

city

centre,

a

modern

development

that

manages to blend

perfectly

with

neighbouring

old

buildings, in this case, the fine examples surrounding Abbey

Green.

Accessed

via

a

narrow

stairway

from

the

City

Walls or via Northgate Street,

you

will

find

some

excellent

cafes and

specialist

shops here and

a

great

live

music & comedy

venue, Alexander's

Bar. Read more about Rufus Court and explore the fascinating businesses to be be found there both on ChesterTourist.com and on their own website...

The

old

houses

on

the

wall

next to

the

Northgate (seen on the right of our snowy photograph),

now

coverted

into

commercial

premises with apartments above,

were erected between 1735 and 1750. The romantic novelist Beatrice Tunstall, author of The Shiny Night (1931), The Long Day Closes (1934) and The Dark Lady (1939) had her home here.

The nearest house to the gate bears

the

distinguished

adress

of

'Number

One,

City

Walls'. The nearest house to the gate bears

the

distinguished

adress

of

'Number

One,

City

Walls'.

By

the

late

1960s,

much

of

this

area

had, in common with much of the Cathedral's estate,

become

exceedingly

run-down. Our photographs show views of Abbey Green

from this time which will prove shocking to those who know and admire the place today.

In addition to proposing improvements to many other threatened parts of Chester, the important Insall

Report of

1968

recommended

that

this area

be

radically redeveloped

to

provide

new

shops

and

maisonettes

facing

upon

Northgate

Street

with

larger

town

houses

behind. However, the

landowners,

the

Dean

and

Chapter,

drew

up

their

own

plans

for the site which included a proposal to

erect

a five-storey

office block immediately

next

to

the

Northgate,

which

was

intended

to

fund

both

the

housing

scheme

and

the

restoration

of

adjacent

listed

buildings.

In

preparation

for

the

redevelopment,

an

extensive

archaeological

investigation

was

conducted

which

led

to

the

discovery

of

substantial

portions

of

the

Roman

rampart

and

associated

structures

and

this

in

turn

led

to

much of the

area

being

scheduled

as

an

Ancient

Monument.

Consequently,

severe

restrictions

were

wisely

placed

upon

any

new

building.

The

Cathedral

authorities,

pleading

lack

of

money,

had

long neglected

their

historic properties

hereabouts

until, in 1978, the appoinment of

a

new

Dean

brought a fresh spirit and, assisted

by

grants,

a

radical

programme

of long-overdue repairs

was

embarked

upon.

In addition, the

new

protected

status

of

the

area

helped

to

persuade

them

to

give

up

any

idea

of

building

over

Abbey

Green

and

of

replacing

the

old

shops

in

Northgate

Street

with

their

speculative office

block,

and

they

thankfully

remain

with

us

today, home to a variety of quality businesses. The

Cathedral

authorities,

pleading

lack

of

money,

had

long neglected

their

historic properties

hereabouts

until, in 1978, the appoinment of

a

new

Dean

brought a fresh spirit and, assisted

by

grants,

a

radical

programme

of long-overdue repairs

was

embarked

upon.

In addition, the

new

protected

status

of

the

area

helped

to

persuade

them

to

give

up

any

idea

of

building

over

Abbey

Green

and

of

replacing

the

old

shops

in

Northgate

Street

with

their

speculative office

block,

and

they

thankfully

remain

with

us

today, home to a variety of quality businesses.

The

City

Council

around

this

time

expressed

an

interest

in

putting

the

excavated

Roman

buildings

on

permanent

public

display

and

of

taking

over

no.1

Abbey

Green

(the

furthermost

building

in

the

top

photograph)

to

serve

as

an

interpretive

centre.

Sadly

this

failed

to

come

about;

the

remains

were

carefully

reburied

and

the

fine

house

continued

to

decay

until

the

early

1990s,

when

it

was

superbly

restored

and

converted

into

a

restaurant

within

the

Rufus

Court

development.

As recently as the the Summer of 2011, as part of the fierce debate surrounding the controversial (and, thankfully, unsuccessful) Cathedral Improvement Proposals, concern of neglect by the Dean & Chapter of their historic properties in the area was once again being expressed in the correspondence pages of the local press- smashed windows and peeling paint on the listed Georgian houses in Abbey Green, damaged cobbled surfaces and empty properties in the beautiful Abbey Square- which we will visit later in our stroll- rubbish accumulating on the Deanery Field, the adjoining and once-charming Deanery Cottage empty and decaying, vehicle damage and nelect of the Abbey Gateway and the area around the Little Abbey Gateway...

You

may

be

interested

in

seeing this remarkable

aerial

view-

a

detail

from

John

McGahey's

famous View

of

Chester

from

a

Balloon- showing

how

the

area

appeared

in

1855.

Roman

Wall

As

you

look

out

from

the

parapet,

you

will

often

observe

people

standing

on

the

bridge

immediately

outside

the Northgate,

peering

through

the

railings

at

the

spectacular

masonry

of

the

North

Wall

and

the

Shropshire Union Canal

running

far

below. You

should

take

the

time

to

join

them

before

we

move

on-

especially

in

springtime,

when

the

entire

length

of

the

wall

base

is

covered

with

a

mass

of

daffodils.

A

stroll

along

the

newly-resurfaced

canal

towpath

below

is

also

highly

recommended

at

some

time

during

your

visit-

access

is

through

an

archway

in

the

wall

close

to Morgan's

Mount or

via

the

wooden

steps

near

the Kaleyard

Gate- as the view upwards of the epic masonry of the North Wall, and the sandstone palateau upon which it was built- is unrivalled anywhere. As

you

look

out

from

the

parapet,

you

will

often

observe

people

standing

on

the

bridge

immediately

outside

the Northgate,

peering

through

the

railings

at

the

spectacular

masonry

of

the

North

Wall

and

the

Shropshire Union Canal

running

far

below. You

should

take

the

time

to

join

them

before

we

move

on-

especially

in

springtime,

when

the

entire

length

of

the

wall

base

is

covered

with

a

mass

of

daffodils.

A

stroll

along

the

newly-resurfaced

canal

towpath

below

is

also

highly

recommended

at

some

time

during

your

visit-

access

is

through

an

archway

in

the

wall

close

to Morgan's

Mount or

via

the

wooden

steps

near

the Kaleyard

Gate- as the view upwards of the epic masonry of the North Wall, and the sandstone palateau upon which it was built- is unrivalled anywhere.

Two views of Rufus Court today: a civilized oasis in the heart of a historic city- no matter what the weather!

The

masonry

immediately

below

the

parapet-

best

viewed

from

the

aforementioned

bridge

or, as mentioned,

from

the

towpath-

deserves

your

close

attention

as

it

is

the

finest

surviving

stretch

of actual Roman

stonework

in

the

entire

circuit;

laid

in

place,

amazingly,

almost two thousand years

ago- c. 90 to 120 AD-

and

bearing

witness

to

the

skill

of

the

Legionary

engineers

in

utilising

only

the

best

available

stone

in

the

construction

of

their

defences.

Our photograph below shows the view from the bridge outside the Northgate. On the left runs the Shropshire Union Canal and its towpath. Above it rises the escarpment of Triassic sandstone upon which the old fortress was built. The City Wall is built on top of this- you can clearly see the original Roman portion standing proud of the later, medieval masonry. Our photograph below shows the view from the bridge outside the Northgate. On the left runs the Shropshire Union Canal and its towpath. Above it rises the escarpment of Triassic sandstone upon which the old fortress was built. The City Wall is built on top of this- you can clearly see the original Roman portion standing proud of the later, medieval masonry.

This marvellous vista had been considerably curtailed due to the unchecked proliferation of sycamore trees growing atop the ridge and along the base of the wall. These had attained a considerable height, thoroughly obscuring the view- and doubtlessly causing all manner of damage to the ancient masonry. Eventually, in 2010, a radical programme of improvements was initiated which cleared the growth and made good damage to the wall.

Much

of

the

material

for

the

construction of the fortress

was

labouriously

transported

from

a

large

quarry

on

the

far

side

of

the

River

Dee,

today

a

park

known

as Edgar's

Field which

supplied

fine

building

stone

throughout

the

Roman

occupation

and

after.

Additional

supplies

of

building

stone

also

came

from

sources

nearer

to

hand,

such

as

that

excavated

during

the

construction

of

the

deep

defensive

ditch

or fosse which

we

see

before

us

carrying

the

canal and the area just across the canal. The large quarry here recently came to light again- after being filled in for centuries- when the bus station which occupied the site was demolished. We will learn more of this shortly...

In

1711,

there

was

a

mention

of

a "quarry

near

the Phoenix

Tower" and

the

site

of

another

small

local

quarry,

known

as

the Abbey

Quarry still

exists

just

behind

the

buildings

on

the

far

side

of

Abbey

Green

and

is

today

utilised

for

car

parking.

Excavated

at

the

base

of

the

natural

sandstone

escarpment,

the fosse,

during

the

centuries

of

Roman

occupation

would

have

been

carefully

kept

clear

of

any

debris

and

vegetation

by

which

a

potential

enemy

might

gain

cover

or

even

a

handhold

to

assist

in

scaling

the

wall. Maintainance

ceased

with

the

withdrawal

of

the

Legions,

and

subsequent

natural

erosion,

as

well

as,

in

those

less-than-scrupulous

times,

domestic

waste

of

all

kinds

being

disposed

of

by

simply

being

thrown

over

the

wall,

over

the

course

of

centuries

resulted

in

the

fosse

filling

up

and

virtually

disapearing. By

the

13th

century,

the

section

below

us

was

occupied

by

a

low-lying,

unsavoury

sounding

thoroughfare

by

the

name

of Boggelone (Bog

Lane)

which

ran

parallel

with

the

wall

immediately

outside

the

Northgate.

At

the

commencement

of

the Baron's

War in

1264,

between

Henry

III

and

his

barons,

led

by

Simon

de

Montfort,

steps

were

taken

to

put

the

city

into

a

state

of

defence,

much

to

the

distress

of

the

monks

of Chester

Abbey-

partly

due

to

the

fact

that

they

sympathised

(but

not

too

openly)

with

De

Montford,

but

also

because

they

owned

houses

in

Bog

Lane,

which

were

demolished

when

the

old

Roman

defences

were

re-excavated.

The

restored

defensive

ditch

also

prevented

access

to

the

monk's

vegetable

gardens

outside

the

East

Wall,

the Kaleyards,

and

later "It

was

ordered

that

a

drawbridge

should

be

put

across

the

fosse

at

the

Kaleyard

Gate". At

the

commencement

of

the Baron's

War in

1264,

between

Henry

III

and

his

barons,

led

by

Simon

de

Montfort,

steps

were

taken

to

put

the

city

into

a

state

of

defence,

much

to

the

distress

of

the

monks

of Chester

Abbey-

partly

due

to

the

fact

that

they

sympathised

(but

not

too

openly)

with

De

Montford,

but

also

because

they

owned

houses

in

Bog

Lane,

which

were

demolished

when

the

old

Roman

defences

were

re-excavated.

The

restored

defensive

ditch

also

prevented

access

to

the

monk's

vegetable

gardens

outside

the

East

Wall,

the Kaleyards,

and

later "It

was

ordered

that

a

drawbridge

should

be

put

across

the

fosse

at

the

Kaleyard

Gate".

These

precautions

did

not

prevent

the

city

being

briefly

captured

soon

after

by

the

Earl

of

Derby,

but

the

monks

eventually

got

their

revenge,as

he

was

afterwards, "Imprisoned

for

a

long

time

in

the

Tower

of

London,

on

account

of

his

many

excesses

of

authority,

and

especially

on

account

of

the

injuries

done

by

him

to

ecclesiastics".

After the restoration of peace, the old fosse presumably resumed its ancient role as town dump and, though it is shown on Braun's map of 1573, it evidently filled up again and by the start of the 17th century part of it was being used as a pinfold- a place to confine straying animals. Lavaux's map of 1745 shows no trace of it whatsoever. Today, we so take for granted the presence of the canal that, studying our enlarged details of Lavaux's map, the townscape appears distinctly odd minus its deep cutting running hard under our City Walls.

Actually, this was very nearly the situation that could have prevailed today, for, in the early 1770s, when the canal's route was being planned, the original intention was to take it along the far (north) side of Gorse Stacks, George Street and Canal Street- hence the latter's name! Excavation along this route seems to have actually commenced- the February 1879 edition of the Cheshire Sheaf contained this contribution from one Mr Charles Candlin of Mold, "It has struck me, as to the original line proposed for the Canal near the Northgate, that a hollow, lying about 100 yards behind the houses on the north side of George-street, and parallel with it, is a remain of the first cutting. To confirm this, on going down the entry at No. 17, you will see the rock cut three or four yards deep; and behind No. 28 a strong wall in the same line, and about the same height above the hollow, which is now partly filled with cottages at right angles with the street. No doubt when the tumble-down houses, recently bought by the Town Council, are removed from the corner of George-street and Victoria-road, some further trace may be found at the north end of the houses, though these latter were no doubt standing when the Canal itself was built".

However, just before the work was actually commenced, the canal company's directors, for some reason, vacillated in their judgment, and asked the contractor to adopt the southern limit of their deviating powers, and so carry the canal close under and parallel with the City Walls. The original line involved continuous and heavy excavation through the sandstone rock; and the contractor, feeling that the question of a few yards either way could make no very great difference to him, accepted the proposition of the directors. Judge the surprise of all concerned, when it was found that the new line actually took the course of the ancient Roman fosse, excavated some 1500 years before, and for long ages filled up and made solid ground! The result was that the contractor made a considerable fortune by his undertaking. However, just before the work was actually commenced, the canal company's directors, for some reason, vacillated in their judgment, and asked the contractor to adopt the southern limit of their deviating powers, and so carry the canal close under and parallel with the City Walls. The original line involved continuous and heavy excavation through the sandstone rock; and the contractor, feeling that the question of a few yards either way could make no very great difference to him, accepted the proposition of the directors. Judge the surprise of all concerned, when it was found that the new line actually took the course of the ancient Roman fosse, excavated some 1500 years before, and for long ages filled up and made solid ground! The result was that the contractor made a considerable fortune by his undertaking.

It is unclear whether the new course had been adopted when this entry appeared in the City accounts: "1772, May 18. To a gratuity by Mr. Mayor's order on his cutting the first sod of ye Canal £5 5s 0d". But, by a year later, it is clear that the changes had been made, for we read, "1773, May 10. Paid Mr. Golborne for his Trouble in Surveying, Levelling, and reporting ye Course of ye Canal and ye guarding of ye Walls and City Buildings £3 3s 0d". The Corporation would naturally be anxious to ascertain whether the projected new course would in any way jeopardise the City Walls and adjacent buildings. That Mr. Golborne's report was not unfavourable to the scheme may be inferred, as we hear of no opposition to it.

A month afterwards is the following entry: "1773. June 10. Paid Mr. Read for measuring part of ye Ho. of Correction Garden taken by ye Proprietors of ye Canal £0 7s 6d". It is but reasonable to suppose that if the altered course had been the one commenced by the Mayor in 1772, the payments to Messrs. Golborne and Read would have appeared at a much earlier date, as their work must have taken place before May of that year. The House of Correction stood on the plot of ground between George Street and the North Wall and survived into the age of photography, for we see on the left of this old picture. The garden belonging to it once extended up to the Wall itself, and would not have been interfered with had the Canal been constructed along the line first determined upon. A month afterwards is the following entry: "1773. June 10. Paid Mr. Read for measuring part of ye Ho. of Correction Garden taken by ye Proprietors of ye Canal £0 7s 6d". It is but reasonable to suppose that if the altered course had been the one commenced by the Mayor in 1772, the payments to Messrs. Golborne and Read would have appeared at a much earlier date, as their work must have taken place before May of that year. The House of Correction stood on the plot of ground between George Street and the North Wall and survived into the age of photography, for we see on the left of this old picture. The garden belonging to it once extended up to the Wall itself, and would not have been interfered with had the Canal been constructed along the line first determined upon.

Civil War Defences

There

was

even

less

evidence

of

a

ditch

here

later

in

the

17th

century,

during

the

Civil

War

Siege

of

Chester,

when

there

was

a

danger

of

this

stretch

of

wall

being

breached

by

cannon

and

mortar

fire,

allowing

access

to

the

Parliamentary

attackers.

Great

piles

of

earth

were

raised

against

the

insides

of

the

wall

to

prevent

this-

although

the

defenders

may

only

have

had

to

reinforce

the

existing

embankments

surviving

from

the

remains

of

the

Roman

turf

ramparts

which

preceded

the

erection

of

permanent

stone

walls.

These

old

earthworks,

now

planted

with

trees,

remain

clearly

visible

around

the

edge

of

the

Deanery

Field

to

this

day.

You

can

gain

access

to

this

field,

a

very

pleasant

spot indeed,

by

going

down

the

steps

into

Rufus

Court

and

turning

left

along

Abbey

Green.

We

are

grateful

to

correspondant

Richard

Edkins

for

the

following: "During

the

1970s

I

served

as

voluntary

assistant

to

the

Museum

photographer,

Tom

Ward,

during

the

Abbey

Green

section

of

the

North

Wall

excavations.

If

you

examine

the

site

report,

you

will

find

that

the

Civil

War

entrenchments

were

dug

through

the

Roman

turf

and

timber

backing

mound

of

the

Wall.

The

mural

buildings

built

into

the

mound

included

well-preserved

Roman

baking

ovens

and

storehouses,

partly

destroyed

by

Civil

War

entrenchments

and

by

the

1940s

excavations

of

Professor

Robert

Newstead. The

grim

reality

of

warfare

was

shown

by

large

numbers

of

flattened

and

spent

musket

balls

embedded

in

the

back

of

the

Civil

War

trench.

If

my

memory

serves

me

correctly,

the

attack

was

at

dawn

on

7th

July

1644,

and

was

successfully

beaten

off".

In

1995,

shards

of

pottery

found

here

and

assumed

to

be

of

Iron

Age

origin,

were

identified

by

the

British

Museum

as

actually

being Neolithic (c.

3500-1700BC)

making

them

the

first

examples

of

pottery

of

this

period

known

from

Cheshire,

and

a

graphic

illustration

of

the

great

antiquity

of

human

occupation

of

this

site.

More

prehistoric

artefacts

came

to

light

during

at

Chester's

Roman amphitheatre in

the

Summer

of

2000,

when,

during

an

excavation

led

by

archaeologist

Keith

Matthews,

a

volunteer

discovered

a

Neolithic

flint

blade

dating

from

around

4000 BC,

and

later

an

arrow

or

spear

point

from

around

4500 BC

came

to

light-

a

period

before

widespread

farming

when

hunters

roamed

the

land

in

search

of

deer

and

wild

boar.

Roman

Memorials

During

repairs

to

the

North

Wall

near

to Morgan's

Mount in

1883,

the

workmen

were

surprised

to

discover

large

quantities

of

sculpted

and

inscribed

stones

packed

into

the

wall's

interior.

When,

four

years

later,

in

1887,

further

repairs

were

carried

out

in

the

vicinity

of

the

Deanery

Field,

a

great

many

similar

finds

were

made.

It

was

soon realised

that these

were

of Roman origin and

a

systematic

investigation

was

commenced. By

the

end

of

1892,

over

two

hundred

complete

or

fragmentary

pieces

had

been

recovered.

Most

of

these

were

tombstones

which

seem

to

have

been

taken

from

a

nearby

cemetery

situated

outside

the

fortress.

Burials

were

not

allowed

within

Roman

forts and

cemeteries

were

commonly

located

in

prominent

positions

on

either

side

of

the

approach

roads. During

repairs

to

the

North

Wall

near

to Morgan's

Mount in

1883,

the

workmen

were

surprised

to

discover

large

quantities

of

sculpted

and

inscribed

stones

packed

into

the

wall's

interior.

When,

four

years

later,

in

1887,

further

repairs

were

carried

out

in

the

vicinity

of

the

Deanery

Field,

a

great

many

similar

finds

were

made.

It

was

soon realised

that these

were

of Roman origin and

a

systematic

investigation

was

commenced. By

the

end

of

1892,

over

two

hundred

complete

or

fragmentary

pieces

had

been

recovered.

Most

of

these

were

tombstones

which

seem

to

have

been

taken

from

a

nearby

cemetery

situated

outside

the

fortress.

Burials

were

not

allowed

within

Roman

forts and

cemeteries

were

commonly

located

in

prominent

positions

on

either

side

of

the

approach

roads.

Over the heather the wet wind blows,

I've lice in my tunic and a cold in my nose.

The rain comes pattering out of the sky,

I'm a wall soldier, I don't know why.

The mist creeps over the hard grey stone,

My girl's in Tungria; I sleep alone.

Aulus goes hanging around her place,

I don't like his manners, I don't like his face.

Piso's a Christian, he worships a fish;

There'd be no kissing if he had his wish.

She gave me a ring but I diced it away;

I want my girl and I want my pay.

When I'm a veteran with only one eye

I shall do nothing but look at the sky.

W H Auden: Roman Wall Blues |

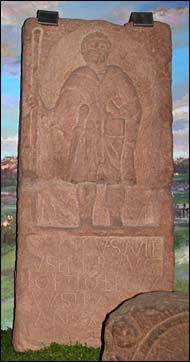

Generations

of

soldiers

had

been

buried

there

and

the

tombstones

recorded

the

names,

ranks

and

sometimes

portraits

of

these

deceased

warriors

and

members

of

their

families,

and

commonly

included

a

carving

of

a

wild

boar,

the

symbol

of

the

XXth

Legion. They

range

in

date

from

around

70 AD

to

the

early

third

century

and

represent

every

type

of

citizen:

soldiers

and

civilians,

men

and

women,

young

and

old-

from

France,

Spain,

Italy,

Slovenia

and

Turkey.

Illustrated

here is

a

typical

memorial

stone

from

the

North

Wall.

It

measures

50

inches

high

by

25

inches

wide

and

contains

a

full-length

portrait

of

the

deceased,

under

which

is

inscribed: "To

the

memory

of

Caecilius

Avitus

of

Emerita

Augusta, Optio of

the

Twentieth

Legion,

who

served

for

fifteen

years

and

lived

thirty

four

years.

His

heir

had

this

erected."

The nature of the emergency that led to

these

memorial stones

being

hauled from their cemetery and built into the fabric

of

the

wall remains entirely mysterious, and probably always will.

Despite

the

undoubted respect

the

Romans

had

for

their

dead,

it

seems

they

were

no

sentimentalists-

they

had

lived

and

died

for

the

Empire

and

now

their

tombstones

would

contribute

further

to

its

defence.

Whatever

the

cause,

for

us

at

least

it

was

a

fortunate

event,

for

these antique memorials

that would normally have been long lost and forgotten have

remained

fresh

and

unweathered

and

many of them are

now

proudly

displayed

in

their

own

gallery

at

the spendid Grosvenor

Museum-

one

of

the

most

important

collections

of

Roman

inscriptions

and

sculpture

anywhere in

Europe.

We

highly

recommend

you

take

the

time

to

visit

them,

together

with

the

superb

mural

by

Chester-based

artist

Gregory

Macmillan

which

vividly recreates in exquisite detail the fortress of Deva Victrix as it may have appeared when these stones were still standing in their lost cemetery.

One of the stones in the gallery, that of Callimorphus and his young son Serapion, was discovered in a former Roman cemetery on the other side of the city, close to what is now Britain's oldest racecourse, the curiously-named Roodee. Learn more here.

Maintaining the Walls (or otherwise?)

This

photograph

shows

the

North

Wall

as viewed from

the

far

side

of

the

canal.

Clearly

visible

is

the

face

of

the

Triassic

sandstone

outcrop

upon

which

Chester

sits-

liberally

decorated

by

a

mass

of

spring

daffodils

and

topped

by

the

splendid

Roman

masonry

and

Thomas

Harrison's

Classical Northgate. Compare

this

with Moses

Griffith's view

in

the

previous

chapter.

As previously observed, this view has altered somewhat in the twenty years since the photograph was taken due to the large number of saplings that have been allowed to thrive unchecked on top of the escarpment and along the base of the wall. As previously observed, this view has altered somewhat in the twenty years since the photograph was taken due to the large number of saplings that have been allowed to thrive unchecked on top of the escarpment and along the base of the wall.

From

1307,

Chester

collected

revenue

for

the

maintainance

of

its

walls

and

other

defences

by

exacting

a

toll

known

as murage upon

all

goods

entering

the

town

that

could

not

be

carried

by

hand.

For

this

purpose,

tollhouses

were

erected

outside

the

gates

and

the

small

building

you

can

see

on

the

right

of

the

Northgate

in

this

picture

is

the

city's

only

surviving

example,

though

much

altered

and

long

since

converted

to

a

private

residence. If

someone

refused

to

pay

the

toll,

the

gatekeeper

had

the

right

to

take

the

bridle

off

his

horse.

The

last

time

this

happened,

the

horse

bolted

and

ran

amok-

an

incident

that, it is said,

contributed

to

the

eventual

ending

of

the

practice.

Murage

was

also

charged

on

goods

carried by ships entering

the Port

of

Chester.

At

the

end

of

the

18th

century,

a

duty

of

two pence

was

charged

on

every

100

yards

of

Irish

linen

imported.

In

1786,

about

five

and

a

half

million

yards

entered

the

port,

excluding

that

destined

for Liverpool,

which

also

paid

duty

to

Chester.

These

tolls

were

eventually

abolished

in

1835.

In October 2006, something of an almighty row broke out regarding the state of our precious walls as more and more people started to notice a decline in their condition, including loose stonework and hand rails and weeds- even small trees (see above)- growing from them. It is certainly the case that the nearby Morgan's Mount has, sadly, long been closed off from visitors for safety reasons. (the inexplicable and unforgivable closure of the Phoenix, Water and Bonewaldesthorne's Towers remains another matter, however).

It was alleged that vital maintainance work had not been carried out for some considerable time and the funds set aside for the purpose had instead been spent on other projects including planning for the restoration of Chester Railway Station and its surroundings. Much hand-wringing ensued- not to mention a great deal of accusation and name-calling between political parties- and a council working party reported that, much as they wished it otherwise, there simply wasn't enough money avilable to do the job properly and desperate appeals were made to central government to make up the shortfall. It was alleged that vital maintainance work had not been carried out for some considerable time and the funds set aside for the purpose had instead been spent on other projects including planning for the restoration of Chester Railway Station and its surroundings. Much hand-wringing ensued- not to mention a great deal of accusation and name-calling between political parties- and a council working party reported that, much as they wished it otherwise, there simply wasn't enough money avilable to do the job properly and desperate appeals were made to central government to make up the shortfall.

Right: a rich mixture of architectural styles- 18th century cottages, 19th century school, chapel, pub (the excellent, but recently-closed, Ship Victory- the only pub in Britain to bear that distinguished name), 1960s apartment blocks and car parks- is visible as we reach the northeast corner of the City Walls.

For many centuries past, when keeping the walls in good order was seen as vital to the safety and well-being of the city, laws to ensure that all who did business here contributed to the cost of their upkeep were strictly enforced. Today, it remains equally vital- albeit for economic and cultural, rather than defensive reasons- that Chester's City Walls and Rows are maintained to the highest possible standards.

Is it not reasonable then, and especially in the face of likely government indifference, that the ancient practice of murage should be revived and that the numerous big business interests currently developing hotels, nightclubs, housing and retail complexes in and around our city, confident as they doubtless are of extracting large profits, should not, perhaps as a condition of their planning permission, to be compelled to do their bit and give a little back?

Fear mongering became reality a few months later, however, when the stretch of City Wall adjoing the Grosvenor Precinct was actually closed to the public. It seemed that a section of adjoining 18th century brick wall started to signs of collapse. It once formed the rear wall of an 18th stable block which was unaccountably allowed to remain in place when this was demolished to make way for the precinct. The walkway remained closed to the public for several months until, with reassurances that all was well, reopening. But much more serious trouble was to follow a few months later, in April 2008. Work had recently started on removing the troublesome brick wall when a great stretch of the ancient City Wall itself collapsed onto the recently-erected scaffolding. The entire stretch has now been sealed off and it will now, sadly, remain closed for the forseeable future. It seems that the 'scaremongers' were right all along. Go here for the latest...

Extensive

maintainance work was

carried

out

on

the

outer face of the North Wall

between

the Northgate and

the Phoenix

Tower during

the

severe

winter

of

1981-82.

This

necessitated

the

erection

of

scaffolding

from

the

canal

towpath

some

fifty

feet

below

and

the

masons

working

in

this

exposed

position

compared

conditions

to

the "north

face

of

the

Eiger"...

In November 2009, a structural problem was detected- a wall lying up against the City Wall in Rufus Court (see above) has become detached and a programme of repairs is to be embarked upon during December and January 2010. This will necessitate the temporary closure of this section of the wall walkway and also of the canal towpath below. As part of the work, we believe that the damaging trees on the face of the North Wall are to be removed. By the Spring of 2010 all of the above work was completed. The damaging saplings are gone and their stumps have been treated to, hopefully, prevent their return and the scene looks very much more like it appeared in the colour photograph higher up this page. In November 2009, a structural problem was detected- a wall lying up against the City Wall in Rufus Court (see above) has become detached and a programme of repairs is to be embarked upon during December and January 2010. This will necessitate the temporary closure of this section of the wall walkway and also of the canal towpath below. As part of the work, we believe that the damaging trees on the face of the North Wall are to be removed. By the Spring of 2010 all of the above work was completed. The damaging saplings are gone and their stumps have been treated to, hopefully, prevent their return and the scene looks very much more like it appeared in the colour photograph higher up this page.

At the time of this most recent update, late Summer 2014, scaffolding continues to prop up the steps to the Northgate (closing Water Tower Street in the process) and the City Wall behind Rufus Court. Down at the River Dee, the Recorder's Steps are similarly propped up and the nearby wall adjoining the access to the Roman Garden has been closed to the public for 'safety reasons'. The Watergate, too, continues to be encased in scaffolding and plywood. We're told that funding for putting this right will not become available until at least 2017! Things appear to be getting worse rather than better.. At the time of this most recent update, late Summer 2014, scaffolding continues to prop up the steps to the Northgate (closing Water Tower Street in the process) and the City Wall behind Rufus Court. Down at the River Dee, the Recorder's Steps are similarly propped up and the nearby wall adjoining the access to the Roman Garden has been closed to the public for 'safety reasons'. The Watergate, too, continues to be encased in scaffolding and plywood. We're told that funding for putting this right will not become available until at least 2017! Things appear to be getting worse rather than better..

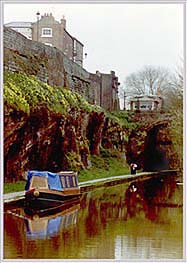

Looking down from the North Wall for the first time, visitors are often unnerved by the terrifying drop to the canal below and the lack of protection offered by the low stone parapet. Unsurprisingly, a number of accidents have occured over the years at this spot when people have tragically fallen to their deaths. Floral tributes may be seen on the towpath below and the sharp eyed may spot this small brass plaque (right) attached to the face of the cutting.

The

Coming

of

the

Canal

In

the

middle

of

the

18th

century,

the

canal

builders- the 'navigators'-

came

to

Chester

and

it

was

decided

that

the

course

of

their

new

cut

should

run

outside,

and

parallel

with

the

line

of

the

North

Wall. It was originally intended to construct a tunnel here but when the

contractors,

expecting

to

have

to

cut

through

solid

rock,

were

surprised

to

encounter

the

long-forgotten

Roman

defensive ditch,

changed their plans and undertook the deep cutting we see today.

The discovery doubtlessly led to a great saving, but the

job

still cost £80,000- around £5 million today-

and

was

completed

in

1779.

We

will

hear

more

of

the

opening

of

Chester's

canal

shortly,

when

we

reach

the Kaleyard

Gate.

Of recent years, the

towpath

alongside

the

canal

was

exceedingly

poorly

maintained

and

as

a

result

was

frequently

waterlogged

and

muddy,

giving

rise

to

numerous

complaints

from

its users.

Despite

all

manner

of

prevarication

from

British

Waterways,

the money was found and a

much-needed

restoration was finally

undertaken

and

all of Chester's extensive system of towpaths are

now

a

delight

to

cycle

and

walk

upon.

The

section

that

passes

under

the Phoenix

Tower and

the

old

sandstone

arch

outside

the Northgate is

quite

spectacular

and

well

worth deviating from your walk around the City Walls to investigate.

Chester

is

a

popular

centre

for

canal

holidays

and

in

the

summer

months,

as

you

look

down

from

the

wall,

you

will

see

many

craft

passing

by,

on

their

way

into

rural

Cheshire, to Ellesmere Port or

via

the

spectacular Llangollen

Canal into

North

Wales. Chester

is

a

popular

centre

for

canal

holidays

and

in

the

summer

months,

as

you

look

down

from

the

wall,

you

will

see

many

craft

passing

by,

on

their

way

into

rural

Cheshire, to Ellesmere Port or

via

the

spectacular Llangollen

Canal into

North

Wales.

Once,

however,

these

canals

were

the

motorways

of

their

day

and

Chester

was

an

important

junction

and

distribution

centre

in

the

system.

From

the

last

quarter

of

the

Eighteenth

Century

to

the

end

of

the

Second

World

War,

generations

of

horse-drawn

working

craft

would

have

passed

this

way,

which

not

only

carried

all

manner

of

heavy

goods,

but

were

also

homes

to

the

bargees

and

their

often-large

families.

Where

the

canal

turns

the

corner

under

the

Phoenix

Tower,

you

can

still

clearly

see

where

their

tow ropes

have

worn

deep

grooves

into

the

sandstone (illustrated left). Nearby canal bridges exhibit the same phenomena, only on these, the grooves have been worn into solid cast iron!

We

will

learn

more

of

the Chester Canal

when

we

visit Tower

Wharf,

later

in

our

stroll and also on these pages, especially devoted to the subject.

As

we

proceed

further

along

the

North Wall,

on

the

right

and

behind

Rufus

Court,

we

see

the

pleasant

garden

area

known

as Abbey

Green,

behind

which

are

some

handsome

18th

century

houses,

and

in

the

background

rises

the

tower

of

our fine Gothic Town

Hall.

The

bases

of

two

vanished

Roman

interval

towers

lie

under

the

grass

at

our

feet.

The

bricked-up

doorway

on

the

wall

to

our

right

was

built

in

1768

by

one Thomas

Boswell

as

an

entrance

to

Abbey

Green

and

a

long-vanished bowling

green

built

on

the

Abbey

orchard. You can see it just to the left of the lamp post in this misty winter's day view. The

bases

of

two

vanished

Roman

interval

towers

lie

under

the

grass

at

our

feet.

The

bricked-up

doorway

on

the

wall

to

our

right

was

built

in

1768

by

one Thomas

Boswell

as

an

entrance

to

Abbey

Green

and

a

long-vanished bowling

green

built

on

the

Abbey

orchard. You can see it just to the left of the lamp post in this misty winter's day view.

(These attractive, crown-topped former gaslamps that light this stretch of the North Wall are of an unusual design, in that they incorporate a hinged mechanism, enabling their upper sections to be swung down to walkway level, thus avoiding the danger of anyone changing the bulbs slipping from their ladder and plummeting into the chasm below).

A contributor to the sadly-defunct Cheshire Sheaf (of which more below) in February 1913 wrote the following, "people familiar with the walls of Chester between King Charles' Tower and the Northgate will, no doubt, have noticed a door, set in a frame of brickwork, and opening upon steps leading to the quiet cul-de-sac known as Abbey Green. The little group of houses bearing this adress, with their cobbled approaches, their frontages of mellowed brick and regular rows of windows, although possessing no great individuality, are of a certain interest by reason of their air of solid comfort and respectability, and on account of the rapid rate at which dwelling houses of this period are being deserted for those of a more recent type, which, if they offer a greater variety to the eye, cannot, in many instances, compare with the former as regards material and workmanship. The doorway was apparently made as a result of a petition to the Mayor and Corporation enrolled in the Assembly Book under the date 30 September 1768. In it Thomas Boswell stated that he had lately erected several houses on a piece of land between the Abbey Court and the Walls of the City, and was desirous of having a footway off the Walls to the said houses, but was prevented from having such way by a rail lately fixed to the Walls. He therefore prayed leave to cut off about a yard of the said rail so as to open a way as desired. An inspection was ordered and evidently the petitioner eventually received a favourable answer".

The local press of July 1817 informed its readers that, "Miss Marianne Briscoe, reflecting with gratitude upon the kind interest, favour and partronage which she has already experience in her Ladies' Boarding School in Abbey Green, Chester, hopes that her assiduous care to promote those mental, personal and religious acquirements which are of such infinite importance in the formation of the female character, will ensure for her establishment the encouragement and approbation of the public". The local press of July 1817 informed its readers that, "Miss Marianne Briscoe, reflecting with gratitude upon the kind interest, favour and partronage which she has already experience in her Ladies' Boarding School in Abbey Green, Chester, hopes that her assiduous care to promote those mental, personal and religious acquirements which are of such infinite importance in the formation of the female character, will ensure for her establishment the encouragement and approbation of the public".

The Cheshire Sheaf, incidentally, was a “notes and queries” column, in which contributors asked and answered questions about all aspects of local history, culture and folklore. It was published in the pages of the local press between the years 1878 and 1990. In 2006, the entire vast archive was lovingly collected together and published as a searchable 2-CD set by Cheshire and Chester Archives and Local Studies. A fabulous research tool- and a lively read for anyone interested in the history of our city and county- it may be purchased here. Much of it may also be read online for free here.

Immediately

after passing by Abbey Green,

visible

across

the

larger Deanery

Field rises the venerable Chester

Cathedral,

which

we

will

shortly

be

visiting. Excavations

on

this

field

have

shown

that

this

section

of

the

Roman

fortress

was

largely

occupied

by

barrack

blocks-

over

sixty

of

which,

each

housing

a

'century'- eighty

men

and

a

centurion,

were

packed

within

the

walls. For

centuries

after

this

whole

area

was

occupied

by

gardens

and

cultivated

land,

remarkably

remaining

unbuilt-upon

to

this

day.

As late as 1855, as is shown in this detail from John McGahey's remarkable aerial view of Chester, cattle grazed on the field. These

agricultural

areas

within

the

walls

were

a

common

feature

of

medieval

Chester,

doubtlessly proving to be valuable assets during times of siege, places of safety for domestic animals brought in from surrounding farms. Today

the

verdant Deanery

Field

is

the last survivor and to our visitors is perhaps

a

surprising

sight

in

such

a

small,

closely-packed

city

centre.

And long

may

it

remain

so! We will learn more of it soon, when we reach The Kaleyard Gate.

Modern Times

The modern age is very much in evidence as we look across the canal from the North Wall. A

Primitive

Methodist

Chapel, shops and pub

formerly

stood

where

the Delamere

Street

Bus

Station until recently was located. (Some pictures of the area as it once was are here.) Its demolition commenced during the late summer of 2005 and the site will be partially utilised as an underground car park as part of the massive- and controversial- Northgate Redevelopment scheme and also for the erection of shops and apartments. By April 2008, work on excavating the ground was well advanced. Our photograph shows the fascinating sight of an ancient quarry, exposed to view for the first time in centuries. The modern age is very much in evidence as we look across the canal from the North Wall. A

Primitive

Methodist

Chapel, shops and pub

formerly

stood

where

the Delamere

Street

Bus

Station until recently was located. (Some pictures of the area as it once was are here.) Its demolition commenced during the late summer of 2005 and the site will be partially utilised as an underground car park as part of the massive- and controversial- Northgate Redevelopment scheme and also for the erection of shops and apartments. By April 2008, work on excavating the ground was well advanced. Our photograph shows the fascinating sight of an ancient quarry, exposed to view for the first time in centuries.

Work proceeded as far as the erection of the car park's steelwork in the bed of the old quarry and then ground to a halt, a situation that remains at this most recent updating in September 2011. However, around this time, developers Watkin Jones announced a new proposal for the site, a £20 million vast and charmless utilitarian building housing a combination of council offices, 149 student apartments and a National Health Service 'super centre'.

Soon after the first 'artist's impressions' (below) hit the local press, the Chester Civic Trust expressed their criticism of the proposed structure, saying they were "disappointed" with the design and dubbing it "obtrusive and out of scale with the immediate surroundings, particularly Northgate Street and the City Walls". They added, "the sheer height of the proposed buildings.. will produce a gloomy canyon of an inner courtyard. The north-facing rooms in the student block will be dark and have a cramped, unpleasant outlook".

The Civic Trust observed that these proposals would be an immediate test of a 'manifesto for contemporary design' demanded by Chester's people under the new One City Plan. This states that "a number of recent developments [the vile new Travelodge and its neighbouring apartment block being just two examples], by general consent, have fallen short of the level of excellence of design to which the city aspires and deserves". In order to be considered a 'must-see' city, the One City Plan says that developments must be designed and implemented "to the highest possible contemporary standard". Hear hear to that we say.

However, in late December 2011, we learned that councillors had overwhelmingly voted in favour of the massive new development, which the Civic Trust described as "mediocre" and "monstrous in scale". Their spokesman, John Henson said "the firm [Watkin Jones] that brought you the Travelodge and the social housing block on the Ring Road is now about to bring you an even bigger development looming over the whole of Northgate Street and the City Walls". He queried the council's competence to consider the application in an unbiased way, given that it would be one of the occupiers. However, in late December 2011, we learned that councillors had overwhelmingly voted in favour of the massive new development, which the Civic Trust described as "mediocre" and "monstrous in scale". Their spokesman, John Henson said "the firm [Watkin Jones] that brought you the Travelodge and the social housing block on the Ring Road is now about to bring you an even bigger development looming over the whole of Northgate Street and the City Walls". He queried the council's competence to consider the application in an unbiased way, given that it would be one of the occupiers.

A test of a 'manifesto for contemporary design'? Failed.

Beyond

the building work,

on

the

site

now

occupied

by

Chester's

main

swimming

baths

and

indoor

sports

venue,

the Northgate

Arena (illustrated above),

from 1875 to 1969 formerly

stood

the

old Northgate

Railway Station. (for those wishing to learn more, an excellent website about it is here- part of Disused Stations).

Chester is not renowned for the quality of its 1960s / 70s architecture but to many, this writer included, the Arena is an exception. Its interior may possibly be in need of some sprucing up and the building would benefit from an extension to provide extra sports and leisure facilities, but there is, in theory, ample room to allow for that. Encased in parts in maturing greenery and surrounded by trees, the Northgate Arena is a handsome building that does much to relieve the somewhat grim environment of the Inner Ring Road and its pools and other facilities are extremely popular with local people. In January 2008, it beat over 450 other entrants to be named the best leisure centre in the UK by the Association for Public Service Excellence (APSE).

The

large

open

space

outside

the

wall

at

this

point

was

for

centuries

common land and

known

by

the

curious

name

of the Gorse

Stacks,

owing

to

part

of

it

at

one

time

being utilised

for

the

safe

storage

outside

the

walls

of

brushwood

and

suchlike

fuel

for

baker's

ovens.

Formerly, firewood had been merely stacked up anywhere that was convenient, often in close proximity to the wooden houses and shops. Consequently, when fire broke out, the results were extensive and disastrous and records show that great areas of the town were destroyed by fire on numerous occasions over the centuries. After the Great Fire of London in 1666, new laws were introduced which forbade the storing of fuel within occupied areas and open land such as Gorse Stacks were instead utilised.

In early Anglo-Saxon times, the area had been called 'Henwald's Lowe', a combination of an Old English personal name and the Old English hlaw, meaning 'mound' or 'hill'. We have no idea who Henwald was, but must presume that he was a personage of importance whose burial followed the tradition of taking place on an area of elevated ground overlooking his former domains. Today, no trace remains of old Henwald's hill and the area

has become a fairly unattractive

place

used

for

car

parking and

its future

has

for

long

been

the

subject

of

much

local

debate.

Once

the

centre

of

a

thriving

commercial

district

centred

upon

the Cattle

Market,

which

was

demolished

in

the

1960s

to

make

way

for

a

traffic

island

on

the Inner

Ring

Road,

it

is

generally

accepted

to

be

in

urgent

need

of

improvement.

Major

reports

in

1964

and

1968

recommended

the

area

be

redeveloped

and the

building

of

a

hotel

here

was

proposed,

but

not

acted

upon,

at

the

end

of

the

1980s.

Then,

in

1995,

it

was

proposed

to

enclose

the

entire

area

within

a

new Millennium

Wall,

within

which

would

be

created

a

landscaped

'cultural

quarter'

containing

galleries,

shops,

restaurants

and

the

like-

plus

a

new

public

square

and

open

air

market. I t

was

estimated

that

the

project

would

cost

an

astonishing £118 million, much

of

which

was

expected

to

come

from

the

private

sector

and

local

authority,

but

over £60

million

was

applied

for

from

the

Millennium

Commission-

unsuccessfully, to nobody's great surprise. Without

this

crucial

funding,

the

entire

project

foundered

and

no

mention

of

it

has

since

been

heard-

although,

independently

of

this,

many of us in Chester have expressed a strong desire

that

a

much-needed, purpose-built

concert

hall,

cinema, exhibition

and

arts

complex be built somewhere in our city centre. Major

reports

in

1964

and

1968

recommended

the

area

be

redeveloped

and the

building

of

a

hotel

here

was

proposed,

but

not

acted

upon,

at

the

end

of

the

1980s.

Then,

in

1995,

it

was

proposed

to

enclose

the

entire

area

within

a

new Millennium

Wall,

within

which

would

be

created

a

landscaped

'cultural

quarter'

containing

galleries,

shops,

restaurants

and

the

like-

plus

a

new

public

square

and

open

air

market. I t

was

estimated

that

the

project

would

cost

an

astonishing £118 million, much

of

which

was

expected

to

come

from

the

private

sector

and

local

authority,

but

over £60

million

was

applied

for

from

the

Millennium

Commission-

unsuccessfully, to nobody's great surprise. Without

this

crucial

funding,

the

entire

project

foundered

and

no

mention

of

it

has

since

been

heard-

although,

independently

of

this,

many of us in Chester have expressed a strong desire

that

a

much-needed, purpose-built

concert

hall,

cinema, exhibition

and

arts

complex be built somewhere in our city centre.

We may have entertained views for or against the ill-fated Millennium Wall, but in the Spring of 2004 we first heard news of a truly dotty plan hatched up by Chester City Council and Dutch insurers/property developers ING- who were also supposed to be undertaking the controversial Northgate Redevelopment- for the erection of a massive new glass and steel council headquarters building on Gorse Stacks. The proposed design, however, was, to say the least, unpopular, attracting a great deal of ridicule and has ever since been referred to- most appropriately, as our illustration shows- as "The Glass Slug".

Prince Charles, the Earl of Chester, to the annoyance of those local politicians who thought erecting such as this in a historic city centre was a bright idea, made it known that he thought the design was horrible too. Prince Charles, the Earl of Chester, to the annoyance of those local politicians who thought erecting such as this in a historic city centre was a bright idea, made it known that he thought the design was horrible too.

Soon afterwards, local elections were held. The Conservatives had pledged that, should they be elected, they would cancel the building. They did take control of the formerly Lib Dem / Labour-dominated council, for the first time in many years- and they did cancel the Slug. Ironically, in the Summer of 2009, another row broke out regarding the Conservative's plan to move into a 'glass palace' of their own- the details of which may be found here...

There remains no trace of the Northgate Development plans seven years after they were proposed, and what the future holds for the sorely-neglected Gorse Stacks area of Chester we can only wait and see.

But

now,

reaching

the

northeast

corner

of

the

City

Walls,

we

see

rising

before

us

the

venerable Phoenix

Tower...

Curiosities from Chester's History no. 3

1069 Chester was the last remaining great town in England

to fall to the Conqueror's sword during the final stages of the Harrying

of the North in 1069-70, fully three years after the Battle of Hastings.

Numerous rumours had long been circulating about the difficult roads, the

position of the city (surrounded as it was by marshes and great forests),

of its numerous inhabitants- and of their obstinate courage: "Locorum asperitatum

et hostium terribilem ferocitatem". Many of William's nobles, worn out by

the struggles in the North and alarmed at these rumours, demanded their discharge.

Some actually retired to Normandy, abandoning the lands with which they had

already been rewarded; but the persuasive powers of Duke William prevailed-

he promised them great rewards, and, as the conquest of Chester was the last

of his projects, they would find rest after their victory. As it turned out,

as the Norman army drew near, the city (whose citizens had doubtless heard

equally terrifying rumours regarding the approaching foe) surrendered without

opposition. William granted the Earldom of Chester first to Walter de Gherbaud-

who, however soon returned to Normandy- and then to his nephew, Hugh D'Avranches-

know as 'Lupus' (the wolf) and, in later life, 'Hugh the Fat'- "To hold to

him and his heirs as freely by the sword as the King holds the Crown of England".

The Earldom became very powerful and virtually independent of the Crown, the

Earl having his own Parliament consisting of eight of his chosen Barons and

their tenants, and they were in no way bound by any laws passed by the English

Parliament with the exception of treason. The Castle was rebuilt and greatly enlarged and strengthened (becoming the 'caput' of

the Earldom)- as were the City Walls. 1069 Chester was the last remaining great town in England

to fall to the Conqueror's sword during the final stages of the Harrying

of the North in 1069-70, fully three years after the Battle of Hastings.

Numerous rumours had long been circulating about the difficult roads, the

position of the city (surrounded as it was by marshes and great forests),

of its numerous inhabitants- and of their obstinate courage: "Locorum asperitatum

et hostium terribilem ferocitatem". Many of William's nobles, worn out by

the struggles in the North and alarmed at these rumours, demanded their discharge.

Some actually retired to Normandy, abandoning the lands with which they had

already been rewarded; but the persuasive powers of Duke William prevailed-

he promised them great rewards, and, as the conquest of Chester was the last

of his projects, they would find rest after their victory. As it turned out,

as the Norman army drew near, the city (whose citizens had doubtless heard

equally terrifying rumours regarding the approaching foe) surrendered without

opposition. William granted the Earldom of Chester first to Walter de Gherbaud-

who, however soon returned to Normandy- and then to his nephew, Hugh D'Avranches-

know as 'Lupus' (the wolf) and, in later life, 'Hugh the Fat'- "To hold to

him and his heirs as freely by the sword as the King holds the Crown of England".

The Earldom became very powerful and virtually independent of the Crown, the

Earl having his own Parliament consisting of eight of his chosen Barons and

their tenants, and they were in no way bound by any laws passed by the English