|

ontinuing

with

our

exploration

of

the

Kaleyards

area

of

Chester's

ancient

circuit

of

City

Walls,

we

pass by the lovely Deanery Field and encounter

the

picturesque Deanery

Cottage on our right (illustrated

here

under

heavy

snow)

and

soon

the

atmosphere

changes

as

we

enter

the

environs

of Chester

Cathedral. ontinuing

with

our

exploration

of

the

Kaleyards

area

of

Chester's

ancient

circuit

of

City

Walls,

we

pass by the lovely Deanery Field and encounter

the

picturesque Deanery

Cottage on our right (illustrated

here

under

heavy

snow)

and

soon

the

atmosphere

changes

as

we

enter

the

environs

of Chester

Cathedral.

If

you

feel

the

need

to

take

a

picnic break

and

feel

some

green

grass

under

your

feet,

you

can

gain

access

to

the aforementioned venerable and charming open space through

the

wooden

gates

next

to

the

cottage. Access is also available from the end of Abbey Green, off Northgate Street.

The Deanery Cottage was long allowed to fall into disrepair but has recently been renovated and converted into student accomodation.

Moving

on,

our

attention

is

drawn

to

the

handsome

large

arched

window

of

the

house

standing

on

the

corner

of

cobbled Abbey

Street (just

visible

beyond

the

cottage

in

our

photograph).

Like

so

many

of

Chester's

fine

buildings,

this

house

is

a

product

of

centuries

of

change

and

alteration:

the

eighteenth

century

facade

fronts

a

seventeenth

century

house,

which

in

incorporates

an

even

earlier

stone

building.

It was

not

always

the

handsome

structure

we

see

today,

however.

In

fact,

by

1976,

when

it

served

as

eight

'bed

sitters',

its

condition

had

deteriorated

to

a

degree

that

it

was

thought

to

be

beyond

economic

repair.

But,

with

the

aid

of

numerous

grants,

in

1983-4

the

house

was

restored-

including

the

rebuilding

of

the

entire

north

gable

with

its

lovely

Gothic

arched

window-

and

converted

into

four

fine

apartments.

The Abbey Gateway and Square

Continuing

on

down Abbey

Street,

with

its

elegant

terrace

of

Georgian

houses

along

one

side

and

the

Cathedral

Green

on

the

other,

we

soon

come

to the

lovely Abbey

Square,

which

was

laid

out as a speculative development

by

the

Cathedral

authorities

in

the

middle

of

the

18th

century

on

the

site

of, amongst other things,

the

old

brewery, bakehouse, stables

and

suchlike concerns that served the needs of the monastery, its many visitors and guests and, for a while, of the Cathedral church that succeeded it. Continuing

on

down Abbey

Street,

with

its

elegant

terrace

of

Georgian

houses

along

one

side

and

the

Cathedral

Green

on

the

other,

we

soon

come

to the

lovely Abbey

Square,

which

was

laid

out as a speculative development

by

the

Cathedral

authorities

in

the

middle

of

the

18th

century

on

the

site

of, amongst other things,

the

old

brewery, bakehouse, stables

and

suchlike concerns that served the needs of the monastery, its many visitors and guests and, for a while, of the Cathedral church that succeeded it.

The

Abbey,

and

later Cathedral,

precincts

had

always

been

independent

of

the

jurisdiction

of

the

City

and,

doubtless

much

to

the

irritation

of

the

civic

authorities,

all

manner

of polluting industries

were

carried

out

behind

the

protection

of

high walls and the

great

14th

century Abbey

Gateway (of which more below).

Right: the Abbey Gateway, an etching by George Cuitt (1779-1854)

In

addition,

the

Abbey

was

not

subject

to

the

extremely

restrictive

trading

regulations

of

the

town

and

'strangers'-

those

who

were

not

Freemen

of

Chester-

could,

as

long

as

they

paid

their

dues

to

the

Abbot,

trade

here

without

requiring

the

permission

of

the

Mayor

and

Burgesses.

The

stench

of

the

brewery

and

other

annoyances

would

long remain

a

source

of

complaint

to

the

townsfolk (and others- see below)

until

they

were

swept

away

when

the

area

was

transformed

into

Chester's

first

formal

square,

built

"after

the

London

fashion"

between

the

years

1754

and

1761-

although

the

western

terrace

(parallel

with Northgate

Street)

was

not

completed

until

the

1820s. This extract from a letter to the Dean & Chapter from the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1637 would seem to indicate that the area's former noisome activities had attracted official disapproval, and at the same time provides a description of the area before the coming of Abbey Square:

"I am informed, that in yor Quadrangle or Abbey Cort of Chester, wherein my Lord the B'p of Chesters house and yor owne houses stand, the B'ps house takes up one side of the Quadrangle And that another side hath in it the Deanes house and some buildinges for singing men: That the third side hath in it one Prebende's house onelie, and the rest is turned to a Malthouse; And that the fourth side (where the Grammar Schoole stoode) is turned to a Comon Brewhouse, and was lett into lives by yor unworthie Predecessors. This Malthouse and Brewhouse, but the Brewhouse espetiallie, must needes by Noise and smoke and filth infinitlie annoy both my Lord the B'ps house and your owne, And I doe much wonder that any man of Ordinarie Discretion should for a little trifling gayne bring such a Mischiefe (for less it is not) uppon the place of theire owne Dwellinge.” "I am informed, that in yor Quadrangle or Abbey Cort of Chester, wherein my Lord the B'p of Chesters house and yor owne houses stand, the B'ps house takes up one side of the Quadrangle And that another side hath in it the Deanes house and some buildinges for singing men: That the third side hath in it one Prebende's house onelie, and the rest is turned to a Malthouse; And that the fourth side (where the Grammar Schoole stoode) is turned to a Comon Brewhouse, and was lett into lives by yor unworthie Predecessors. This Malthouse and Brewhouse, but the Brewhouse espetiallie, must needes by Noise and smoke and filth infinitlie annoy both my Lord the B'ps house and your owne, And I doe much wonder that any man of Ordinarie Discretion should for a little trifling gayne bring such a Mischiefe (for less it is not) uppon the place of theire owne Dwellinge.”

Left: an evocative view of Abbey Square sometime in the 1950s by the great Liverpool photographer Edward Chambré Hardman. All that has changed since is the cars!

The Bishop of Chester at that time, Bishop Bridgeman, would appear to have been in agreement, as he replied to Archbishop Laud, "ever since my being Bishop of this Sea (which is now almost 20 years) I have scarce had a month's health together, while I lived at Chester, by means of the smoake and the annoyance which came thereby"...

On

the

eastern

side

of

the

square,

which

was

initially

known

as Abbey

Court,

between

a

large,

free-standing

18th

century

house

and

the

Cathedral,

a

group

of

humble

sandstone

cottages

curiously

escaped

the

redevelopment

and

two

(they

formerly

stood

back-to-back

with

two

others)

remain with us

to this day.

They

were

built

in

1625

by

Bishop

Bridgeman

on

the

site,

and

incorporating

part

of

the

structure

of,

the

Abbey's

kitchens,

to

house

lay

clerks

of

the

Cathedral. They

continue

to

serve

as

private

residences

in

the

ownership

of

the

Dean & Chapter.

The

south

side

of

the

square

was

dominated

by

the Bishop's

Palace.

This

had

been

badly

damaged

in

the

Civil

War

and

so eventually, a century later,

between

1754

and

1757,

was

rebuilt.

Local author and guide Joseph

Hemingway

was

evidently

unimpressed

with

the

result,

describing

the

new

palace

as

being "as

destitute

of

magnificence

as

it

is

of

elegance". This second palace duly disappeared in its turn and its

site

is

now

occupied

by

a handsome Victorian pile housing a bank and offices. The

present

Bishop's

residence,

built

later

in

the 18th

century,

is

situated

behind

the

high

wall

on

the

opposite corner

of

Abbey Square.

You may notice the

causeways

of

weathered York

stone

laid

between

the

cobbles

in

the

square.

These are

known

as 'wheelers' and

were

thoughtfully

provided

to

allow

the

residents'

carriages with their solid wheels and primitive suspension

a

slightly smoother

ride. They

still

serve

their

purpose

very

well

for

today's

bicycles!

The

lower

part

of

the

pillar

in

the

middle of the central

grassy

area,

which

was

formerly

surrounded

by

iron

railings,

is said to have been

rescued

from

the Exchange-

the

predecessor

of

the

Victorian

Town

Hall

we

know

today-

in

nearby

Northgate

Street,

after it

was

destroyed

by

fire

in

1862.

Another version is that, a

hundred

years

earlier,

during

the

early

stages

of

the

building

of

Abbey

Square,

the

pillars

supporting

one

side

of

the

Exchange

were

found

to

be

weakening

and

so

were

removed

and

the

space

filled

with

a

row

of

shops

and

one

of

them

was

presented

by

the

city

to "the

gentlemen

of

Abbey

Square". The

grassed

area

where

it

was

erected

was

formerly

occupied

by

a

stinking

and

polluted

pond,

'the Horse

Pool' which,

in

1523

claimed

the

life

of

one

Roger

Ledsham, "Keeper

of

the

Great

Gate

of

the

Abbey

of

St. Werburgh" when

he

fell

in

it

and

was

drowned.

Could it have been that

the

proximity

of

the

Abbey's

brewhouse

played

some

small part

in

the

tragedy?

The great Abbey Gateway, seen above in an early 19th century engraving by George Cuitt, that now links Abbey Square with Northgate Street and the Market Square dates from the fifty-first year of the reign of Edward III, 1377 (the last of his long reign), in which year he granted a licence for the monks to crenellate their abbey- in other words, to enclose it within high walls with fortified entrances. Some authorities say the gateway actually predates this event, being erected around 1300. The style of the gateway is Decorated, though late in that style. Walking beneath it will reveal its groined vault with ribs, in the centre of which still survives a sculptured statuette in bas-relief, probably a depiction of the patron saint of the Abbey, Saint Werburgh. Look out for the iron hinges where the great wood and iron-reinforced doors once hung. On the right hand side of the interior of the gateway, as viewed facing out to the Market Square, is an area of sandstone bearing deep grooves. This is where the armed monks guarding the portal would, in idle moments, have sharpened their weapons. The great Abbey Gateway, seen above in an early 19th century engraving by George Cuitt, that now links Abbey Square with Northgate Street and the Market Square dates from the fifty-first year of the reign of Edward III, 1377 (the last of his long reign), in which year he granted a licence for the monks to crenellate their abbey- in other words, to enclose it within high walls with fortified entrances. Some authorities say the gateway actually predates this event, being erected around 1300. The style of the gateway is Decorated, though late in that style. Walking beneath it will reveal its groined vault with ribs, in the centre of which still survives a sculptured statuette in bas-relief, probably a depiction of the patron saint of the Abbey, Saint Werburgh. Look out for the iron hinges where the great wood and iron-reinforced doors once hung. On the right hand side of the interior of the gateway, as viewed facing out to the Market Square, is an area of sandstone bearing deep grooves. This is where the armed monks guarding the portal would, in idle moments, have sharpened their weapons.

The upper part of the structure, with its 16-pane window in a Gothic arch, was rebuilt in 1800.

The Abbot's fair was held in front of the Abbey Gate for 3 days from the Feast of the Translation of St, Werburgh, the 21st of June. At Whitsun the Mystery Plays were performed by the members of the city's 25 companies of guildsmen. The earliest recorded performance of the plays was in 1566 or 1567 but they are believed to be much older than this. They were suppressed after the Reformation but revived in 1951 and are now performed by Chester's people every five years.

Just a little further down Northgate Street may be seen what remains of a secondary entrance into the precinct, the Little Abbey Gateway. Only the outer arch remains and it is unknown if a fortified gatehouse also once existed here. What does survive, noticed by virtually nobody, but as you will see should you step through the arch into what is currently a scruffy car parking area, is a small section of that once-formidable defensive wall, now built into the rear of the once-grand 18th century houses (now converted to shops and offices) in Northgate Street.

We invite you to view our gallery of images, old and new, of the two venerable Abbey Gateways here.

The anonymous author of the early 19th century work, A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, wrote of the Abbey Gateway, "which is a noble entrance of two Gothic arches, included within a round one of great diameter... over the arch of the gate-way is the Register's Office, consisting of large convenient rooms, surrounded with neat oak cases where the wills are kept, and two smaller rooms for the Register and his clerks. On the front of the gate are two niches; in one of which the image of Hugh Lupus was used to placed during the fairs."

Of the square itself he wrote, "The Abbey Court is a neat square, within an obelisk and grass plot, enclosed by a neat iron railing; there are handsome modern-built houses on two sides; the Bishop's palace filling up the south side, which is a plain stone pile, built by Bishop Keene, in 1753, upon the walls of the ancient Abbot's house. The house in which the Dean resides, was lately built upon the walls of St. Thomas's Chapel, and is a commodious handsome building. The Prebends, Minor Cannons and Vicars Choral, have houses within the Abbey Court." Of the square itself he wrote, "The Abbey Court is a neat square, within an obelisk and grass plot, enclosed by a neat iron railing; there are handsome modern-built houses on two sides; the Bishop's palace filling up the south side, which is a plain stone pile, built by Bishop Keene, in 1753, upon the walls of the ancient Abbot's house. The house in which the Dean resides, was lately built upon the walls of St. Thomas's Chapel, and is a commodious handsome building. The Prebends, Minor Cannons and Vicars Choral, have houses within the Abbey Court."

The first

occupants

of

the

elegant

new

development

were

clergy,

local

gentry

and

private

families

of

means,

but

as

time

passed,

the

rising

class

of

'professionals'

such

as

doctors,

lawyers

and

architects

(including

the

celebrated John

Douglas who

worked

at

number

six

from

1860

until

his

death

in

1911)

came

to

dominate,

and

the

interiors

of

the

majority

of

the

old

houses

were

converted

into

offices

and

other

commercial

premises, a situation that endures to this day.

Nevertheless,

an

air

of

past

times

definitely remains-

this

photograph

shows

how

effectively

the

square

was

utilised by Granada TV

in

a

filming

of

a

scene

from

Thomas

Hardy's Far

From

the

Madding

Crowd- virtually all the producers had to do was to remove the cars and the TV aerials! (Our picture library has many more photographs of this event, should readers be interested).

During the Second World War, number six Abbey Square was requisitioned from architects Messrs Douglas, Minshull and Co. to become the city's ARP (air raid precautions) office. Circulars from the Home Office were continuously received here by the Emergency Committee, with instructions for setting up public shelters, school shelters, decontamination posts, first aid stations and the like. The ARP equipment itself was stored at nearby Folliot House in Northgate Street.

The Little Abbey Court

Making our way back up Abbey Street, the sharp-eyed may spot a small plaque about eight feet up on the wall of one of the houses that provides amusement for anyone acquainted with the long-running TV comedy, 'Last of the Summer Wine', for on it is inscribed "These properties belonging to the Dean and Chapter were renovated in 1979-1980 with the help of a substantial legacy from Mrs Norah Batty". Making our way back up Abbey Street, the sharp-eyed may spot a small plaque about eight feet up on the wall of one of the houses that provides amusement for anyone acquainted with the long-running TV comedy, 'Last of the Summer Wine', for on it is inscribed "These properties belonging to the Dean and Chapter were renovated in 1979-1980 with the help of a substantial legacy from Mrs Norah Batty".

Today, those who pass along Abbey Street may enjoy the sight of a verdant grassy lawn which covers the entire area between the Cathedral, the street and the City Walls, known as the Cathedral Green, where the venerable Mystery Plays used to be performed. But it wasn't always like this, and until the end of the 19th century, much of the area was covered by private houses and the area was known as The Little Abbey Court.

A matter of further interest is that that these houses were constructed from the remains of an important medieval establishment which passed from use with the suppression of the monastery- the Abbey Infirmary. This was used not only for the accomodation of sick monks but also for the lodging of those brothers who, by reason of age and infirmity, were incapable of taking part in the regular routine of the monastery.

Monastic infirmaries generally consisted of an accomodation hall, kitchens and chapel. In time, the central area of the great hall became an open courtyard from where the surrounding cells of the infirm monks could be accessed, as well as the kitchens and, by way of the slype or 'maiden's aisle', the east cloister of the abbey. An outer gateway gave access to the burial grounds and to Abbey Street.

After the Dissolution, the chapel and other buildings became derelict and eventually disappeared but the old cells of the monks were added to and adapted into dwelling houses and these are clearly shown on period maps of the city. After the Dissolution, the chapel and other buildings became derelict and eventually disappeared but the old cells of the monks were added to and adapted into dwelling houses and these are clearly shown on period maps of the city.

Left: Abbey Square today

The last remnants of the kitchens were demolished during improvement work by Dean Cholmondeley in 1809 at which time an old door was discovered and a dark passageway beyond. A witness at the event later recorded how "a light was procured and we went in at least 70 yards in the bowels of the earth, taking a direction apparently south-east. It extended further but we did not advance. Others, more daring, proceeded afterwards a greater distance. It was a regular footway. It is now covered with earth but the entrance to it is marked by a small archway and is about ten feet below the surface. it is to be lamented that this passage was not further explored under authority".

This mysterious passageway, seemingly of Roman origin, was later mentioned in Hansall's Stranger in Chester (1816) and in W T Watkin's great Roman Cheshire (1886), in which some later explorations of the relic are described in which it was said to be circular and at least ten feet in height. Dating from centuries before the establishment of the Abbey, it seems likely that part of the passageway came to light during early construction work and was incorporated into the cellars of the infirmary and later dwelling houses. Its situation today is entirely unknown, by this writer at least.

There were five old houses standing in the Little Abbey Court- also known as the Abbey Close- when the the greater Abbey Court, some distance to the west, was renamed Abbey Square in the middle of the 18th century. As previously noted, they originated from the five lodgings of the sick monks and radiated from a central courtyard. A watercolour of 1875 shows some of the old houses, two-storied structures of red sandstone with upper floors of black-and-white work standing on the north side of the court. On the west side there is an ancient sandstone building, also of two stories, with mullioned windows capped by dripstone mouldings and the ground floor fronts show signs of niche or canopy works. There were five old houses standing in the Little Abbey Court- also known as the Abbey Close- when the the greater Abbey Court, some distance to the west, was renamed Abbey Square in the middle of the 18th century. As previously noted, they originated from the five lodgings of the sick monks and radiated from a central courtyard. A watercolour of 1875 shows some of the old houses, two-storied structures of red sandstone with upper floors of black-and-white work standing on the north side of the court. On the west side there is an ancient sandstone building, also of two stories, with mullioned windows capped by dripstone mouldings and the ground floor fronts show signs of niche or canopy works.

The residents of this secluded little group of houses in the 19th century were, to a considerable extent, connected with the affairs of the Cathedral and it seems likely that the same association applied to those residing here in earlier times- minor canons, organists and the like- and their names and occupations are recorded in the local directories of their day. One of these, a Mr Frederick Gunton, was a teacher of the Cathedral's choristers who would make use of an apple tree which grew in the courtyard to obtain 'instruments of chastisement at choir practise".

All this was to end in December 1884, however, when the entire area was demolished and the green lawns we see today were laid over the venerable foundations. The old apple tree survived the destruction, however, and was recorded as still flourishing in 1918. Our photograph shows the tranquil spot where the monk's infirmary and Little Abbey Court long stood, now being enjoyed by sunbathers.

Rejoining

the

City

Walls

and

looking

over

the

parapet,

we

see

a

tree-lined

area,

now

used

for

car

parking,

and

long

known

as The Kaleyards.

Descending

the stone

steps,

we

see

next

to

them

a

narrow

opening

in

the

wall,

equipped

with

a

stout

oak

door.

This

is

the Kaleyard

Gate and

is

a

smaller

and

less

ancient

affair

than

Chester's

other

gates.

In

1275,

the

third

year

of

the

reign

of

Edward

I,

the

Abbot

of

St. Werburgh's

Abbey

requested

permission

of

the

town

to

construct

a postern in

the

Walls

at

this

place

so

his

monks

could

avoid

having

to

go

round

via

the Eastgate to

attend

to their

vegetable

gardens

situated

outside

the

Walls.

In

these

troubled

times,

when

the

risk

of

armed

attack

by

Prince Llewellyn's

Welshmen

was

a

deadly

reality,

all

of the

city

gates

were

closed

at

curfew-

at

that

time

8.00pm-

and

at

times

of

danger.

Thus,

there

was

considerable

unease

at

the

Abbot's

request,

and

permission

was

only

eventually

granted

as

long

as

the

Abbey

assumed

responsibility

for

closing

their

new

gate

at

curfew

and

for

making

it

secure

during

times

of

crisis.

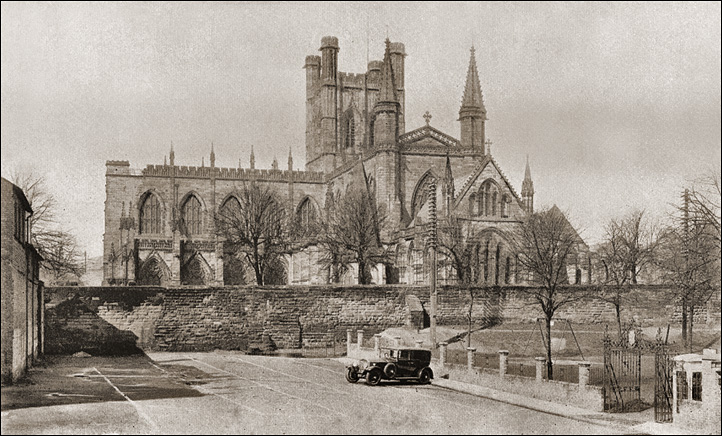

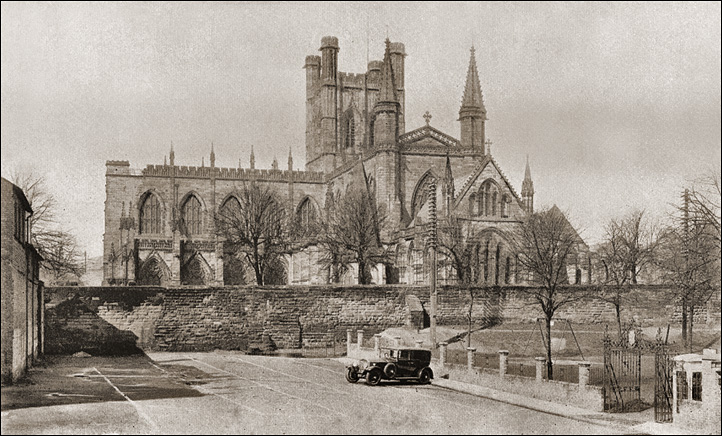

An evocative view of the Cathedral and Kaleyards from the early years of the 20th century

Some

time

later,

the

monks

were

allowed

to

make

yet

another

opening

in

the

walls, "where

the

swine

sty

used

to

be",

the

proposed

door "to

be

of

such

dimensions

that

a

man

on

foot

might

lead

a

horse

through

without

difficulty,

the

same

to

be

closed

in

time

of

war

should

the

safety

of

the

city

require

it."

It

was

also

ordered

that

a "drawbridge

should

be

put

across

the

fosse

at

the

Kaleyard

gate".

This fosse was

a

deep

ditch,

a

standard

feature

of

a

Roman

fortress,

which

ran

outside

the

north

and

east

walls.

Having

filled

up

over

the

centuries

with

the

accumulated

debris

of

the

town,

it

was

re-excavated

at

the

time

of

the

Baron's

war

in

1264

as

a

defensive

measure,

and

was

still

in

existence

in

the

late

16th

century,

when

it

appears

on Braun's Map,

but

has

since

entirely

vanished.

The

northern

section was

re-excavated

for

a third time

in

the

1770s

to

carry

the

bed

of

the

new

Chester

Canal.

(The

contractor,

expecting

to

have

to

excavate

through

solid

rock,

was

doubtlessly pleasantly-

and

profitably-

surprised

to

encounter

the

forgotten

Roman ditch).

Its

presence

at

the

Eastgate

was

first

shown

in

1860,

when

workmen

were

trying

for

a

foundation

for

a

new

building

just

outside

the

gate,

and

had

to

excavate

to

a

depth

of

30

feet

before

they

found

rock

at

the

bottom

of

the

ancient

defensive works.

Despite

the

convenience

of

the

new

openings,

it

would

appear

that

the

safety

of

the

monks

became

an

issue:

after

many

complaints

that

the

garden

was

frequently

robbed

and "the

monks

assailed

with

abuse",

the gardens were surrounded by a high stone wall and the

abbot

actually constructed two gates on the wall walk itself, to further hinder unauthorised access to the gardens. This of course, also prevented the law-abiding from passing by and he was indicted for obstruction in 1352. Nontheless, in 1414, Henry V granted the monks a licence to close these gates on condition that those who maintained the Walls, the Murengers, and those responsible for the city's defence in time of war were always allowed access.

After

Henry

VIII's dissolution of

the

monasteries,

the

duty

of

securing

the

Kaleyard Gate

fell

to

the

Dean

&

Chapter

of

the

newly-created

Cathedral. The Swine

Sty

Postern survived

until

the

late

17th

century,

when

it

was

removed

during

repairs

to

the

Walls

following

the

end

of

the

Civil

War. After

Henry

VIII's dissolution of

the

monasteries,

the

duty

of

securing

the

Kaleyard Gate

fell

to

the

Dean

&

Chapter

of

the

newly-created

Cathedral. The Swine

Sty

Postern survived

until

the

late

17th

century,

when

it

was

removed

during

repairs

to

the

Walls

following

the

end

of

the

Civil

War.

During

this

conflict, Sir

William

Brereton,

leader

of

the

besieging

Parliamentary

forces,

observed

of

the

Kaleyard

Gate, "All

the

ports

made

up

(gates

sealed

up)

and

strong

guards

sett

upon

them,

some

of

them

within

pistoll

shott

soe

that

none

remained

open

but

one

little

sally

porte

whiche

is

betwixt

the

Phenix

Tower

and

the

Eastgate".

The

curfew

is

still

rung

from

the Cathedral belltower

at

8.45

each

evening and the

Kaleyard

Gate is locked

fiteen minutes later,

at

nine

o'clock, and

re-opened

at

sunrise.

It

is

the

only

remaining

city

gate

at

which

this

ancient

custom

is

still

observed

and

originated

in

the

Norman

law

of couvre

feu ('cover

fire'-

which

gave

rise

to

the

modern curfew)

when,

to

ensure

the

safety

of

the

largely

timber-built

town,

the

gates

were

closed

and

all

fires

had

to

be

extinguished.

A few years ago, the Dean and Chapter of the Cathedral, expressing concern that their staff may possibly be assaulted during the carrying out of their duties, did away with seven and a half centuries of tradition and discontinued the evening locking of the Kaleyard Gate. However, in June 2012, the ancient practice was resumed and carried out by a Cathedral Constable, an office that was formed as recently as December 2011 to look after the security of the Cathedral and its Estate.

Mason's

Marks

Passing

through

the

Kaleyard Gate

and

turning

around,

notice

the

great

eruptions

of

Roman

masonry

running

along

the

base

of

the

present

wall

to

our

left

and

note

also

the

variety

of

building

styles

evident

in

stonework

ranging

from

the

1st

to

the

20th

centuries.

You

may

rejoin

the

wall

here

either

by

re-ascending

the

steps

or

walking

up

the

ramp. Passing

through

the

Kaleyard Gate

and

turning

around,

notice

the

great

eruptions

of

Roman

masonry

running

along

the

base

of

the

present

wall

to

our

left

and

note

also

the

variety

of

building

styles

evident

in

stonework

ranging

from

the

1st

to

the

20th

centuries.

You

may

rejoin

the

wall

here

either

by

re-ascending

the

steps

or

walking

up

the

ramp.

Looking

around,

the sharp-eyed may

spot

carved

into

the

triangular

coping

an

anchor

and "692

feet".

This

marks

the

distance

between

here

and

the

Phoenix

Tower

and

represents

the

length

of

the SS Great

Eastern,

the

double-hulled

steam

and

sail

ship

which

was

launched

in

1858

and

used

for

the

laying

of

the

first

transatlantic

telegraph

cable

in

1866.

This

great

vessel,

which

was

originally

called The Leviathan, was

built

in

four

years

by the great engineer

Isambard

Kingdom

Brunel and

weighed

19,216

tonnnes-

several

times

the

size

of

the

largest

ships

of

the

time.

Her

vast

size

greatly

impressed

the

public

mind,

and

especially

that

of

one

Mr

Musgrave,

who

owned

the

timberyard

next

to

Cow

Lane

Bridge,

for

he

commissioned

William

Haswell,

a

master

mason,

to

record

the

event

on

the

wall

here.

This was done in 1858, the year the great ship was launched. Our photograph above shows the inscription still clearly visible, but noticed by few visitors, a century and a half later.

The Great Eastern was designed by Brunel and Scott Russell in 1852 and built at Millwall. She was ready for launching by October 1852 but it was not until January 1858 that she was actually afloat. Her cost was £732,000. Her greatest achievement was the laying of the first transatlantic cable and also similar communications cables in the Mediterranean and Red Seas. By

1874

the Great

Eastern was deemed

obsolete

and

she was sold at auction in 1886 for £58,000, ending

her

days

in

the

River

Mersey

as

a

floating

advertisment

for

Lewis'

department

store,

lying

at

anchor

with

music

hall

shows

and

circus

acts

on

board.

She

was

broken

up

on the seashore at

Tranmere

in

1889, where many of her iron plates may still be discovered, rusting away beneath the sand. Learn much more about her here.

Other interesting marks

may be spotted by the sharp-eyed along

the

City Walls,

such

as

initials,

symbols

and

dates

which

appear

at

numerous

locations around the circuit.

These

were

inscribed

by

the

generations

of

masons

who

have

maintained,

repaired

and

rebuilt

the

walls

over

the

centuries-

Chester's Murengers.

The

earliest

examples

were

left

by

Roman

Centurions

in

charge

of

construction

gangs,

each

of

whom

would

have

been

responsible

for

completing

a

given

length

of

wall. None of these remain in situ but examples may be examined in the Roman Stones Gallery in the Grosvenor Museum. Other interesting marks

may be spotted by the sharp-eyed along

the

City Walls,

such

as

initials,

symbols

and

dates

which

appear

at

numerous

locations around the circuit.

These

were

inscribed

by

the

generations

of

masons

who

have

maintained,

repaired

and

rebuilt

the

walls

over

the

centuries-

Chester's Murengers.

The

earliest

examples

were

left

by

Roman

Centurions

in

charge

of

construction

gangs,

each

of

whom

would

have

been

responsible

for

completing

a

given

length

of

wall. None of these remain in situ but examples may be examined in the Roman Stones Gallery in the Grosvenor Museum.

left: Chester Cathedral from the daffodil-fringed Deanery Field, photographed by the author in 2002.

Chester's

first

Infant

school

was

opened

in

the

Kaleyards,

following

the

forming

of

a

benevolent

society

set

up

for

the

purpose

in

1825,

under

the

direction

of

the-then new

Bishop

of

Chester,

Dr.

Charles Blomfield (in office 1824-48).

A

public

subscription

was

raised

to

pay

for

the

building,

but

when

this

proved

to

be

insufficient,

the

ladies

of

Chester

held

a

grand

bazaar,

which

raised £357,

and

the

new

school

opened

in

July

1826.

The

bazaar

profits

also

helped

the

society

to

extend

their

benevolent

activities

to

other

needy

parts

of

the

city.

The

schools

were

largely

supported

by

the

parents

of

each

child

attending

paying

one

penny

per

week. The old schoolhouse still stands here, albeit converted to a private residence.

On 14th August 1940, a Luftwaffe Heinkel HE III bomber attacked RAF Sealand, causing damage to some of the buildings. Three Spitfires from the nearby Hawarden Airfield were scrambled and attacked the enemy plane as it was making its third bombing run, bringing it down in a field near to Border House Farm in Bumper's Lane (close to where the recycling centre and Chester City FC's stadium is now). The crew all survived and were incarcerated briefly in cells at Chester Castle and spent the rest of the war as prisoners in Canada. As a morale (and fund)-raising exercise, the remains of the Heinkel were put on display in the Kaleyards, together with a money collection box.

Reader Mike Wells wrote to tell us about an even stranger object that was once to be seen here: "I remember being taken on a school trip to see a blue whale. It was on display in the car park at the lower end of Frodsham Street, probably around 1957-8. The whale was a full size sperm, or possibly blue whale. It was mounted and preserved, on an articulated truck. How they managed to drive it around the streets of Chester I do not know. I remember it as part of an exhibition that filled the car park, from the Kaleyard Gate to the back of what became the Witches' Kitchen. I think I was then at the grammar school, although if it was before 1956, I would have been at Westminster Road School. Do you have any record or photographs of the occasion?" Reader Mike Wells wrote to tell us about an even stranger object that was once to be seen here: "I remember being taken on a school trip to see a blue whale. It was on display in the car park at the lower end of Frodsham Street, probably around 1957-8. The whale was a full size sperm, or possibly blue whale. It was mounted and preserved, on an articulated truck. How they managed to drive it around the streets of Chester I do not know. I remember it as part of an exhibition that filled the car park, from the Kaleyard Gate to the back of what became the Witches' Kitchen. I think I was then at the grammar school, although if it was before 1956, I would have been at Westminster Road School. Do you have any record or photographs of the occasion?"

Does anyone else remember seeing this remarkable sight? We've since learned that it was known as 'The Barnsley Whale' was also put on display around this time at the Pier Head in Liverpool. The much-missed DJ John Peel mentioned seeing it on his Home Truths radio show a few years ago. Here is a fascinating illustrated website about it..

Frodsham

Follies

Ahead

of

you

through

the

Kaleyards

is

the

busy

shopping

area

of Frodsham

Street,

formerly

known

as

Cow

Lane because for centuries cattle and other livestock would be driven

from the countryside down this street en route for the beast market that was held in Foregate Street. Later, this situation becoming inconvenient (a new generation of genteel residents and shopkeepers objected greatly to the disruption the herds produced- the proverbial 'bull in a china shop' was often a reality here!)- the

Cattle

Market was transferred to Gorse Stacks at the other end of Cow Lane,

where it thrived until

the

Even

earlier,

Frodsham

Street

was

the

commencement

of

the

Roman

road

which

ran

from

the

fortress,

along

the

line

of

modern

Brook

Street,

through

the

suburb

of

Hoole

(where

these

words

are

being

written)-

and

on

to

Frodsham

and

the Mersey crossing at Wilderspool (Warrington).

Much

of

the

route

remains

in

use

to

this

day-

although

some

sections,

as

at

the

Newton

Hollows

in

Hoole,

are

now

little

more

than

footpaths.

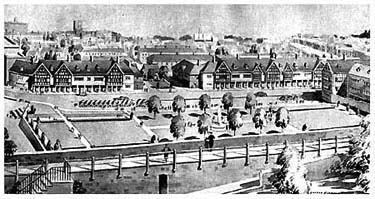

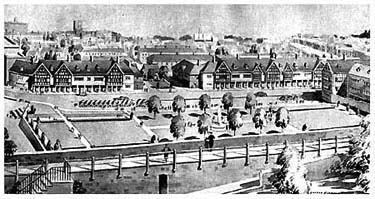

This

slightly

fuzzy,

but

fascinating

'artist's

impression'

is from

the

remarkable Greenwood

Redevelopment

Plan of

1944-

when

this

country

was

still

enmeshed

in

the

Second

World

War-

which

advocated

demolishing

the

entire

west

side

of

Frodsham

Street

and

landscaping

the

area

to

create

a

new

city

park,

and

to

restore

the

area's

ancient

name, the Hop

Pole

Paddock.

How

delightful.

Notice

the

fountain

among

the

trees

in

the

centre.

You

can

also

see

the

familiar

Kaleyard

Gate,

stone

steps

and

ramp

on

the

city

wall

in

the This

slightly

fuzzy,

but

fascinating

'artist's

impression'

is from

the

remarkable Greenwood

Redevelopment

Plan of

1944-

when

this

country

was

still

enmeshed

in

the

Second

World

War-

which

advocated

demolishing

the

entire

west

side

of

Frodsham

Street

and

landscaping

the

area

to

create

a

new

city

park,

and

to

restore

the

area's

ancient

name, the Hop

Pole

Paddock.

How

delightful.

Notice

the

fountain

among

the

trees

in

the

centre.

You

can

also

see

the

familiar

Kaleyard

Gate,

stone

steps

and

ramp

on

the

city

wall

in

the

We

shall

encounter

a

number

of

other

bold

proposals

from

Mr Greenwood's

grand

scheme-

none

of

which,

for

good

or

bad,

were

ever

acted

upon-

during

the

remaining

course

of

our

stroll.

This ancient thoroughfare has undergone numerous changes in modern times. The entire west side (the left, looking from Foregate Street) was demolished to allow it to be widened in the first decade of the twentieth century. Among many businesses lost was the 17th century Raven Inn. (Learn more of it and the other vanished inns of Frodsham Street here.) In the 1960s, a stark shopping development known as Mercia Square (illustrated right) was erected which lasted a mere thirty years before being done away with and eventually replaced by the mediocre collection of shops that stand in this sensitive spot today. See some more photographs of it here.

Yes, times

have

changed,

and

today's

planners

and

commercial

interests

too

often

seem

to

consider

the

open

spaces

within

and

around

our

city-

school

playing

fields,

allotments,

green

fields

and

meadows-

even

Roman amphitheatres,

for

heaven's

sake-

as

mere

'development

opportunities'

to

be

sold

off

and

built

upon. And

indeed,

in

early

2000,

we

were

concerned

to

hear

that

a

company

by

the

name

of Ethel

Austin

Shop

Properties had

sought

planning

permission

to

erect

a

two-storey

building

in

Frodsham

Street,

immediately

next

to

the

pedestrian

access

to

the

13th

century

Kaleyard

Gate,

a

location

described

by

the

city's

conservation

officer

as "an

exceptionally

sensitive

site". Councillors

were

warned

that

the

building

would

be "over

dominant",

would

virtually

fill

this

end

of

the

Kaleyards,

would

necessitate

the

removal

of

all

trees

and

shrubs

(and

no

replacement

landscaping

was

indicated

on

the

plans)-

and

that

it

"owed

nothing

to

local

architectural

styles". Yes, times

have

changed,

and

today's

planners

and

commercial

interests

too

often

seem

to

consider

the

open

spaces

within

and

around

our

city-

school

playing

fields,

allotments,

green

fields

and

meadows-

even

Roman amphitheatres,

for

heaven's

sake-

as

mere

'development

opportunities'

to

be

sold

off

and

built

upon. And

indeed,

in

early

2000,

we

were

concerned

to

hear

that

a

company

by

the

name

of Ethel

Austin

Shop

Properties had

sought

planning

permission

to

erect

a

two-storey

building

in

Frodsham

Street,

immediately

next

to

the

pedestrian

access

to

the

13th

century

Kaleyard

Gate,

a

location

described

by

the

city's

conservation

officer

as "an

exceptionally

sensitive

site". Councillors

were

warned

that

the

building

would

be "over

dominant",

would

virtually

fill

this

end

of

the

Kaleyards,

would

necessitate

the

removal

of

all

trees

and

shrubs

(and

no

replacement

landscaping

was

indicated

on

the

plans)-

and

that

it

"owed

nothing

to

local

architectural

styles".

The Chester

Civic

Trust objected

to

the

proposals,

describing

them

as

being "seriously

inappropriate".

They

noted

that

the

"overblown

scale

of

the

mock

timber

framing

on

the

building,

together

with

other

design

features,

were

objectionable

in

relation

to

the

City

Walls,

shops

and

listed

public

houses

on

Frodsham

Street",

that

the

narrowness

of

the

alley

that

would

be

created

between

existing

shops

and

the

new

structure

would

be

"oppressive

and

potentially

dangerous" and

that

it

would

block

the

only

remaining

viewpoint

outside

the

city

walls

from

where

one

can

see

the

Cathedral

and

Town

Hall

tower.

(and what a

view!)

Given

such

a

body

of

well-reasoned

objection,

councillors

had

little

difficulty

in

wisely

dismissing

the

application

which

was

duly

withdrawn

by

the

aspiring

developers-

who

then

promptly

appealed

to

Environment

Secretary

John

Prescott

on

the

grounds "that

the

council

had

not

decided

its

application"-

and

even

demanded

that

the

council

should

pay

the

costs

of

that

appeal!

By

the

time

this

came

about,

in February

2001,

the

developers

claimed

their

building

had

been "totally

redesigned" and

attempted

to

have

this

version

considered

by

the

government

Inspector.

He,

however,

declined

to

do

so,

explaining

that

an

appeal

must

be

based

upon

the original application

and

that

people

must

be

allowed

time

to

consider

and

comment

upon

the

revised

plans. Both

designs

were

the

handiwork

of

Liverpool-based

architect Craig

Foster, incidentally.

In

their

original

objection,

the

Chester Civic

Trust

had

concluded

that "this

is

a

visually

and

historically

important

site

which

needs

a

distinguished

design

sensitively

related

to

the

local

distinctiveness

of

its

setting". But

better

by

far,

we

say,

would

be

to

reconsider

the

good

Mr

Greenwood's

proposals

of

so

long

ago.

Not,

of

course,

that

we

would

advocate

his

large-scale

demolition

of

existing

buildings,

but

the

adoption

of

the

Kaleyards

as

a

much-needed

'green

lung'-

a

place

of

rest

and

recreation

in

the

heart

of

the

bustling

commercial

centre

of

our

city-

would

certainly

be

much

appreciated

by

residents

and

do

much

to

attract

visitors.

The

current

proposals

for

the

relocation

of

Chester's

smaller

car

parks,

such

as

that

currently

occupying

much

of

the

Kaleyards,

would

surely

add

to

the

viability

of

the

scheme.

The

less-than-attractive

sight

from

this,

probably

the

most

visited

section

of

Chester's

City

Walls,

of

the

back

doors,

rubbish

bins

and

advertising banners

of

the

adjoining, deeply

mediocre Mercia

Square development

makes

it

additionally

important

that

the

remaining

areas

surrounding

the

Kaleyards

should

not

end

up

the

same

way.

A

new

park

here

would

be

an

ideal

location

for

concerts

and

an

open-air

market

too. The

less-than-attractive

sight

from

this,

probably

the

most

visited

section

of

Chester's

City

Walls,

of

the

back

doors,

rubbish

bins

and

advertising banners

of

the

adjoining, deeply

mediocre Mercia

Square development

makes

it

additionally

important

that

the

remaining

areas

surrounding

the

Kaleyards

should

not

end

up

the

same

way.

A

new

park

here

would

be

an

ideal

location

for

concerts

and

an

open-air

market

too.

But

what

were

we

thinking?

This

is

Chester

after

all.

By

the

end

of September

2001,

all

parties

had

kissed

and

made

up

and

Ethel

Austin's

re-design

had

been approved by

city

planners-

and

the ever-compliant

Civic

Trust

now described

it

as

"much

improved".

We

were

told

that

the

design

was

"in

keeping

with

the

mixed

architectural

character

of

Frodsham

Street

and

avoids

obscuring

views

of

the

cathedral".

We

also

heard

that

the

design

is

"supported

by

the

City

Centre

Conservation

Area

Advisory

Committee", whoever they may be.

But, by eight years later, Summer 2009, no sign of the controversial development had yet to be seen- and no surprise, for soon afterwards it was announced that Ethel Austin had gone into receivership! So that, hopefully, was the end of that.

But then, in October 2010, we heard the first of a deeply idiotic proposal to erect Chester's long-delayed new Market Hall, not somewhere on the vast area of dereliction behind the Town Hall as we had long been promised, but right here, on the Kaleyards! Architect's drawings forming part of consultation exercises taking place in January 2011 would appear to show a two-storey wood-faced modern structure with a plastic roof with a bridge walkway connecting it to the City Wall. We say 'appear to' because, for unknown reasons, no actual 'artist's impressions' of the building were made available for the public's enlightenment, merely aerial views of the site with the new building's outline imposed upon them. A skeletal side view of the new Market Hall's dimensions struck us as highly suspicious, appearing as it did to be no higher than the neighbouring shops in Frodsham Street..

Roman parade ground, medieval jousting croft and monks' vegetable garden, Victorian school playground- millennia of open-air usage, all apparently soon to end because a bunch of Dutch speculators in cahoots with a short-sighted local council don't want our market to to be rebuilt in the area where it has traded since Saxon times, in the vicinity of, you've got it- Market Square. According to aspiring developers ING, despite the pack of lies we were fed when they got their hands on it, the great area of land behind the Town Hall is now far too valuable to be wasted upon such trifles as theatres, bus stations, libraries- or Market Halls. All must be reserved for shops, shops and more shops. But not yet, for, intriguingly, rather than being put to good use, the land has just been laid out as a temporary public open space, St. Martin's Park, and will remain so for at least the next decade, awaiting the time when fat profits may once more be gleaned from it. Meanwhile, all of those much-needed community facilities must now be squeezed into what remains of Chester's open spaces such as the Little Roodee and here at the Kaleyards. Utter, utter folly.

But this, too, came to nought and, at the time of this brief update, March 2013, the talking shop regarding the Northgate Scheme goes on and on. Further dodgy developments, past and present, at the other end of the Kaleyards will be told of in our Eastgate chapter...

This remarkable

aerial

view-

a

detail

from

John

McGahey's

famous View

of

Chester

from

a

Balloon- shows

the

Kaleyards

and

their

surroundings

as

they

appeared

in

1855.

We

now

turn

our

attention

to

the

great

and

ancient

building

now rising

before

us: Chester

Cathedral...

Curiosities from Chester's History no. 7

- 1277 The King (Edward I) ordered that all in Cheshire that could spend £20 per annum should be made Knights. He establishes Chester as his base for the conquest of North Wales.

- 1278 The Old Dee Bridge was overthrown by a great flood, and the city was reduced to ruins by a dreadful fire.

- 1279 The Carmelites, or White Friars, established their house in Chester.

- 1281 December: Llywelyn, the last Welsh Prince of Wales, died in a skirmish with Lord Mortimer.

- 1283 (-1323) The building of Caernarvon Castle commenced. The 'Pied Piper of Hamelin'.

- 1290 Grant of land to the Carmelite (White) Friars enables them to build their friary in White Friars Lane.

- 1291 Thomas de Burchelles becomes fourteenth Abbot of St. Werburgh's (-1323)

- 1300 In Chester was received the final submission of the Welsh to the Sovereignty of England by Edward of Caernarfon, the first English Prince of Wales and later King Edward II, when the freemen of the Principality did fealty for their lands. Water from the springs at Christleton was first brought to the Abbey of St.Werburgh in earthenware pipes

- 1307 Edward I died and was succeeded by Edward II (1284-1327). Murage duty was introduced- a tax on goods entering Chester, which was used for the upkeep of the city walls.

- 1322 The Water Tower or Port Watch Tower, a defensive structure standing in the waters of the receding River Dee, was built by John de Helpston for £100- equivalent to around £250,000 in modern currency.

- 1323 William de Bebington becomes fifteenth Abbot of St. Werburgh's (-1349)

- 1327 Edward II was deposed by Parliament and brutally murdered "in a manner which could be seen by no man" (a red hot poker inserted into his back passage) at Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire and was succeeded by his son as Edward III (1312-1377). The Aztecs establish Mexico City

- 1331 Chester's unique Rows are first mentioned by name in the city records- although they almost certainly existed long before this date.

- c. 1340 The Black Death kills a third of England's population. Within five years, it had arrived in Chester; crops rotted in the fields around the city because there were not enough reapers left to harvest them. Abbot William de Bebington died of this plague and was buried in the Abbey Choir.

- 1337 Beginning of the Hundred Years' War

- 1349 The Mayor of Chester, Bartram Northen, was slain by Richard Ditton, who was pardoned upon paying the sum of 150 marks. Richard de Seynesbury becomes sixteenth Abbot of St. Werburgh's (-1362) The Black Death kills a third of the population of England. Boccaccio: The Decameron

- 1353 Edward the Black Prince, Earl of Chester, and an armed force here to protect the justices against a 'commotion', caused by the dearness of provisions due to the effects of the Black Death. The citizens also complained of the cover afforded to robbers and villains in the now-overgrown Forest of Wirral. Edward requested his father to make an order to de-forest it, to which he agreed.

|

"I am informed, that in yor Quadrangle or Abbey Cort of Chester, wherein my Lord the B'p of Chesters house and yor owne houses stand, the B'ps house takes up one side of the Quadrangle And that another side hath in it the Deanes house and some buildinges for singing men: That the third side hath in it one Prebende's house onelie, and the rest is turned to a Malthouse; And that the fourth side (where the Grammar Schoole stoode) is turned to a Comon Brewhouse, and was lett into lives by yor unworthie Predecessors. This Malthouse and Brewhouse, but the Brewhouse espetiallie, must needes by Noise and smoke and filth infinitlie annoy both my Lord the B'ps house and your owne, And I doe much wonder that any man of Ordinarie Discretion should for a little trifling gayne bring such a Mischiefe (for less it is not) uppon the place of theire owne Dwellinge.”

"I am informed, that in yor Quadrangle or Abbey Cort of Chester, wherein my Lord the B'p of Chesters house and yor owne houses stand, the B'ps house takes up one side of the Quadrangle And that another side hath in it the Deanes house and some buildinges for singing men: That the third side hath in it one Prebende's house onelie, and the rest is turned to a Malthouse; And that the fourth side (where the Grammar Schoole stoode) is turned to a Comon Brewhouse, and was lett into lives by yor unworthie Predecessors. This Malthouse and Brewhouse, but the Brewhouse espetiallie, must needes by Noise and smoke and filth infinitlie annoy both my Lord the B'ps house and your owne, And I doe much wonder that any man of Ordinarie Discretion should for a little trifling gayne bring such a Mischiefe (for less it is not) uppon the place of theire owne Dwellinge.” The great Abbey Gateway, seen above in an early 19th century engraving by George Cuitt, that now links Abbey Square with Northgate Street and the Market Square dates from the fifty-first year of the reign of Edward III, 1377 (the last of his long reign), in which year he granted a licence for the monks to crenellate their abbey- in other words, to enclose it within high walls with fortified entrances. Some authorities say the gateway actually predates this event, being erected around 1300. The style of the gateway is Decorated, though late in that style. Walking beneath it will reveal its groined vault with ribs, in the centre of which still survives a sculptured statuette in bas-relief, probably a depiction of the patron saint of the Abbey,

The great Abbey Gateway, seen above in an early 19th century engraving by George Cuitt, that now links Abbey Square with Northgate Street and the Market Square dates from the fifty-first year of the reign of Edward III, 1377 (the last of his long reign), in which year he granted a licence for the monks to crenellate their abbey- in other words, to enclose it within high walls with fortified entrances. Some authorities say the gateway actually predates this event, being erected around 1300. The style of the gateway is Decorated, though late in that style. Walking beneath it will reveal its groined vault with ribs, in the centre of which still survives a sculptured statuette in bas-relief, probably a depiction of the patron saint of the Abbey,  Of the square itself he wrote, "The Abbey Court is a neat square, within an obelisk and grass plot, enclosed by a neat iron railing; there are handsome modern-built houses on two sides; the Bishop's palace filling up the south side, which is a plain stone pile, built by Bishop Keene, in 1753, upon the walls of the ancient Abbot's house. The house in which the Dean resides, was lately built upon the walls of St. Thomas's Chapel, and is a commodious handsome building. The Prebends, Minor Cannons and Vicars Choral, have houses within the Abbey Court."

Of the square itself he wrote, "The Abbey Court is a neat square, within an obelisk and grass plot, enclosed by a neat iron railing; there are handsome modern-built houses on two sides; the Bishop's palace filling up the south side, which is a plain stone pile, built by Bishop Keene, in 1753, upon the walls of the ancient Abbot's house. The house in which the Dean resides, was lately built upon the walls of St. Thomas's Chapel, and is a commodious handsome building. The Prebends, Minor Cannons and Vicars Choral, have houses within the Abbey Court."

After the Dissolution, the chapel and other buildings became derelict and eventually disappeared but the old cells of the monks were added to and adapted into dwelling houses and these are clearly shown on period maps of the city.

After the Dissolution, the chapel and other buildings became derelict and eventually disappeared but the old cells of the monks were added to and adapted into dwelling houses and these are clearly shown on period maps of the city.  There were five old houses standing in the Little Abbey Court- also known as the Abbey Close- when the the greater Abbey Court, some distance to the west, was renamed Abbey Square in the middle of the 18th century. As previously noted, they originated from the five lodgings of the sick monks and radiated from a central courtyard. A watercolour of 1875 shows some of the old houses, two-storied structures of red sandstone with upper floors of black-and-white work standing on the north side of the court. On the west side there is an ancient sandstone building, also of two stories, with mullioned windows capped by dripstone mouldings and the ground floor fronts show signs of niche or canopy works.

There were five old houses standing in the Little Abbey Court- also known as the Abbey Close- when the the greater Abbey Court, some distance to the west, was renamed Abbey Square in the middle of the 18th century. As previously noted, they originated from the five lodgings of the sick monks and radiated from a central courtyard. A watercolour of 1875 shows some of the old houses, two-storied structures of red sandstone with upper floors of black-and-white work standing on the north side of the court. On the west side there is an ancient sandstone building, also of two stories, with mullioned windows capped by dripstone mouldings and the ground floor fronts show signs of niche or canopy works.

After

Henry

VIII's

After

Henry

VIII's  Passing

through

the

Kaleyard Gate

and

turning

around,

notice

the

great

eruptions

of

Roman

masonry

running

along

the

base

of

the

present

wall

to

our

left

and

note

also

the

variety

of

building

styles

evident

in

stonework

ranging

from

the

1st

to

the

20th

centuries.

You

may

rejoin

the

wall

here

either

by

re-ascending

the

steps

or

walking

up

the

ramp.

Passing

through

the

Kaleyard Gate

and

turning

around,

notice

the

great

eruptions

of

Roman

masonry

running

along

the

base

of

the

present

wall

to

our

left

and

note

also

the

variety

of

building

styles

evident

in

stonework

ranging

from

the

1st

to

the

20th

centuries.

You

may

rejoin

the

wall

here

either

by

re-ascending

the

steps

or

walking

up

the

ramp.

Reader

Reader  This

slightly

fuzzy,

but

fascinating

'artist's

impression'

is from

the

remarkable Greenwood

Redevelopment

Plan of

1944-

when

this

country

was

still

enmeshed

in

the

Second

World

War-

which

advocated

demolishing

the

entire

west

side

of

Frodsham

Street

and

landscaping

the

area

to

create

a

new

city

park,

and

to

restore

the

area's

ancient

name, the Hop

Pole

Paddock.

How

delightful.

Notice

the

fountain

among

the

trees

in

the

centre.

You

can

also

see

the

familiar

Kaleyard

Gate,

stone

steps

and

ramp

on

the

city

wall

in

the

This

slightly

fuzzy,

but

fascinating

'artist's

impression'

is from

the

remarkable Greenwood

Redevelopment

Plan of

1944-

when

this

country

was

still

enmeshed

in

the

Second

World

War-

which

advocated

demolishing

the

entire

west

side

of

Frodsham

Street

and

landscaping

the

area

to

create

a

new

city

park,

and

to

restore

the

area's

ancient

name, the Hop

Pole

Paddock.

How

delightful.

Notice

the

fountain

among

the

trees

in

the

centre.

You

can

also

see

the

familiar

Kaleyard

Gate,

stone

steps

and

ramp

on

the

city