hould

you

be

overcome

with

the

urge

to

go

shopping,

you

can

join

Eastgate

and

Foregate

Streets

by

descending

the

steps

on either

side

of

the

Eastgate.

Otherwise,

we

shall

cheerfully

leave

the

commercial

bustle

behind

us

and

continue

on

our

way. hould

you

be

overcome

with

the

urge

to

go

shopping,

you

can

join

Eastgate

and

Foregate

Streets

by

descending

the

steps

on either

side

of

the

Eastgate.

Otherwise,

we

shall

cheerfully

leave

the

commercial

bustle

behind

us

and

continue

on

our

way.

The modern world is very much in evidence on this part of the wall- on our left

we pass the backs of utilitarian shops and offices, through which we see the

large rose window of the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel of 1811 in work-a-day St. John

Street. This was the third church designed by Thomas Harrison, whose work we have encountered throughout our wanderings, though its interior was the work of his assistant and pupil William Cole- who was also responsible for completing work on the great Grosvenor Bridge after Harrison's death. The original bowed, two-storey front of the church was replaced in 1906 with the red-brick facade we see today, with its large nine-light window, filled with Perpendicular tracery, and its interior has also been significantly altered.

Some curious relics survive unnoticed and unvisited in the area between the rear of the church and the City Wall- three old, and very weathered, gravestones and the original name plaque of the first Weslyan Chapel on the site.

Look out also for the pub by the name of the Marlbororough Arms-

no, it's not our mistake- in the course of erecting a new sign, its name was

accidentally misspelled- an extra 'or' being included by a signwriter obviously charging by the letter- but then retained

as a novelty. A proper, unspoiled traditional English pub, it is, however, yet another of the many in Chester that are reputed to be haunted... (see the ghosts entry in our general index for more on this).

The pub itself has been in existence for about 150 years. Previously on the site had been the coach house and stables of the Blossoms Hotel next door. A terrible fire put an end to its days, with many lives of horses and the attendants lost. A few years later, the still half-standing coach house was replaced by the hostelry that is still there today.

One version of the 'ghost' tale tells that it is one of these, a stable boy, who now haunts the pub- another is that it is the shade of an old, bankrupt, landlord, who cut his throat in the cellar..

Only a few days after taking charge of the pub, the licencees preceding the current ones were woken at 3am by the sounds of moving barrels. They ran down to the cellar, but all was fine, no disturbances. They waited until the next day and visited next door, but, of course, people don't crash barrels around in modern hotels, and nobody was in that area all night. Next, the landlady was cleaning the pub at about 2am and felt as though she was being watched. She looked up from the bar and saw an apparition of an old lady dressed in a large white bonnet and a lacy Victorian white dress, next to the fruit machine. Since then many folk have noticed odd goings on and lots of items have been found to have moved. A child, dressed again in Victorian clothes has been seen by a few, wandering around aimlessly upstairs, disappearing after a while of being watched. Evidently the stableboy- or suicidal landlord- have company...

The Blossoms Hotel itself, on the corner of Foregate Street, is a 19th century building standing on exact the site of hosteleries dating back to the early 15th century. 'Blossoms' as an inn name came into use at the Reformation. The signs of inns in the vicinity of churches dedicated to St. Lawrence the Deacon commonly displayed his portrait surrounded by a wreath of flowers. After the Reformation, the idolatrous image of the saint was obliterated but the 'blossoms' remained. This does not explain the Chester inn name as there was no church here dedicated to St. Lawrence but the Chester-London coach service had its terminus at the Blossoms Inn in St. Lawrence Street, close to the Church of St. Lawrence Jewry.

Visit our Lost pubs of Chester pages to learn about hundreds more of our city's vanished pubs and inns.

Returning our attention to the City Walls, the anonymous author of the early 19th century A Walk Round the Walls and City of Chester, recorded that "the scene becomes uninteresting owing to the number of dwelling-houses which have been allowed in former times to have encroached upon the walls". In 1836, author and guide Joseph

Hemingway in his Panorama of the City of Chester, wrote

that

this

section "is

all

of

the

most

uninteresting

description,

closely

crowded

with

buildings

on

both

sides,

and

furnishing

not

a single

object

worthy

of

notice

for

their

elegance

or

antiquity". Twenty years later, Thomas Hughes, in his Stranger's Guide to Chester remarked that "the steps we have just ascended give us but poor 'first impressions' of the Walls, the view being blocked up on either side by most unpicturesque buildings".

Could things possibly get worse? Indeed they could-

on the site of Hughes' "unpicturesque buildings",

beyond

a shabby

bit

of

wooden

fencing

now rises

the

crude

bulk

of

the Grosvenor

Laing Precinct and

its

even

uglier multi-storey

car

park,

opened

in

1971

and

an

outstanding

example

of

the

brutalist

architecture

of

the

period. Could things possibly get worse? Indeed they could-

on the site of Hughes' "unpicturesque buildings",

beyond

a shabby

bit

of

wooden

fencing

now rises

the

crude

bulk

of

the Grosvenor

Laing Precinct and

its

even

uglier multi-storey

car

park,

opened

in

1971

and

an

outstanding

example

of

the

brutalist

architecture

of

the

period.

Apparently concerned at the down-market image indicated by the word precinct, the

management

later tried- not entirely successfully-

to

persuade us to refer to it as

the Grosvenor

Shopping

Centre. But not for long, it seemed, for in January 2003 we learned that the precinct had been sold and the place was imaginatively re-named The Mall Chester. Locals stubbornly persist in continuing to refer to it as the "Precinct", however.

In October 2005, the owners of The Mall announced proposals to erect a large extension to their premises on the opposite side of Pepper Street, linked to the existing shops via overhead walkways. Initial 'artist's impressions', predictably, showed a run-of-the-mill 'modern' design, effectively a glass box, that promised to be anything but a sympathetic addition to Chester's townscape. Gratifyingly, a great deal of

fuss was soon kicked up about the proposals and many objections lodged, especially from residents of the well-kept neighbouring terraced houses, many of which would be required to be demolished to make way for the new development. That a great many commercial properties were already sitting empty in the city centre also came into the debate. The ill-considered scheme has now, we're told, 'gone back to the drawing board' and, nearly six years later- August 2011- nothing more, for the moment at least, has been heard of it. The buildings on the affected site, however, are emptying of tenants and assuming a decidedly neglected air.

Excavation

of

the

three

and

a half

acre

site in

preparation

for

the

construction

of

the

precinct at

the

end

of

the

1960s

revealed

the

extensive, well-preserved remains

of

major Roman buildings; barrack

blocks,

a gymnasium

and

a vast

bath

house "with

walls

up

to

two

hundred

feet

long,

standing

to

twelve

feet

in

height"- amazing relics

of

the

great fortress of Deva from two thousand years ago. Unforgivably,

hardly

a scrap

of

any

of

them

was

preserved in

situ.

Dennis

Petch,

Curator

of

the Grosvenor

Museum throughout

the

1960s,

recalled

bitterly

that, "the

developer

refused

to

give

permission

for

any

formal

excavation

once

his

work

on

the

site

had

begun... with

customary

efficiency

Laing's

immediately

commenced

the

earthworks

for

underground

storage

and

delivery

bays

for

shops

to

be

built

in

the

precinct

above...

it

was

soon

clear

that

the

great

colonnaded

hall

under

the

arcade

formed

part

of

the

same

complex

and

was in

all

probability

one

of

the

earliest

of

the

covered palaestrae of

the

north-western

provinces

of

the

Roman

Empire.

Even

after

the

great

size

and

high

degree

of

preservation

of

the

building

had

been

clearly

demonstrated,

and

protests

against

its

impending

destruction

were

made

at

local

and

national

level,

commercial

considerations

prevailed,

effectively

limiting

our

gathering

of

site

data

to

piecemeal

observation

and

recording

at

the

pleasure

of

the

contractor,

supplemented

by

very

little

formal

excavation.

This

was

not

a very

satisfactory

way

of

proceeding

in

the

case

of

such

an

important

building

which

had

apparently

begun

its

life

in

the

early

years

of

the

fortress

and

was

still

in

use

in

the

third

century.

This

debacle

attracted

a great

deal

of

public

attention

and

criticism,

and

the

upshot

was

a general

conviction

that

such

vandalism

should

not

be

allowed

to

recur".

If

only

that

had

proved

to

be

the

case.

The (now defunct) Cheshire

Observer of

5th

September

1969

quoted

the

Oxford

Professor

of

the

Architecture

of

the

Roman

Empire, Professor

S S

Frere,

then

on

a visit

to

Chester,

as

saying, "It is absolutely disgraceful that modern businesses cannot see the value of

the history of the town where they have their businesses and which they are

expoiting". If

only

that

had

proved

to

be

the

case.

The (now defunct) Cheshire

Observer of

5th

September

1969

quoted

the

Oxford

Professor

of

the

Architecture

of

the

Roman

Empire, Professor

S S

Frere,

then

on

a visit

to

Chester,

as

saying, "It is absolutely disgraceful that modern businesses cannot see the value of

the history of the town where they have their businesses and which they are

expoiting".

Left: some of the massive and substantial remains of the Roman bathhouse complex photographed just before their total destruction in 1964.

Apocryphal tales from this time remain common; we recall speaking with an elderly

gentleman who had been employed upon the preparations for the precinct's foundations.

He told us of the discovery of a large, finely-executed mosaic of an eagle, "made of pieces this big" (indicating with his fingers a

distance of about half an inch)- "we got a wet cloth on it and it came up lovely,

but when the boss saw it, he ordered it to be got rid of pronto".

He

described

how

the

shovel

of

a digger

was

then

scraped

across

the

surface,

completely

obliterating

the

treasure-

which

was

never

even

photographed.

The

developers,

it

seems,

were

concerned

with

getting

the

job

done

on

time

and

were

not

prepared

to

let

a 'few

old

ruins'

stand

in

their

way.

Once

archaeologists

got

further

involved,

they

believed,

the

schedule-

and

the

profits-

would

go

out

of

the

window. He also recalled the "chap in a white van who would call round of an evening and give us a few bob for whatever we'd found, coins and the like, during the day"...

During

demolition

and

site

clearance

work,

the

rear

of

St. Michael's

Arcade

was

sealed

off

by

a wooden

hoarding,

into

which

was

thoughtfully

inserted

a number

of

windows

through

which

the people of Chester

could,

in

the

words

of

eminent archaeologist Dr.

David

Mason, "watch

their

precious

Roman

heritage

being

smashed

up

and

carted

away

on

the

backs

of

lorries" (Roman

Chester:

City

of

the

Eagles,

p. 20).

He knew whereof he spoke for he records in this excellent book how, as a boy, he was one such observer. During

demolition

and

site

clearance

work,

the

rear

of

St. Michael's

Arcade

was

sealed

off

by

a wooden

hoarding,

into

which

was

thoughtfully

inserted

a number

of

windows

through

which

the people of Chester

could,

in

the

words

of

eminent archaeologist Dr.

David

Mason, "watch

their

precious

Roman

heritage

being

smashed

up

and

carted

away

on

the

backs

of

lorries" (Roman

Chester:

City

of

the

Eagles,

p. 20).

He knew whereof he spoke for he records in this excellent book how, as a boy, he was one such observer.

Right: the end of the old Talbot Inn in Newgate Street in 1964. A photograph of it taken just before its destruction is on our Vanished Pubs of Chester pages...

Our

elderly informant

cited

similar

examples

during

the

construction

of

the Inner

Ring

Road and

the

orgy

of

commercial

redevelopment

in

and around

the

city

centre

at

that

time

and

our

conversations

with

numerous

construction

workers

have

since

revealed

similar

anecdotes.

(all

further

contributions

gratefully

received!)

Interestingly,

the

small

seaside

resort

of Prestatyn,

a few

miles

along

the

North

Wales

coast,

not

(deceptively)

otherwise

noted

for

its

antiquities, has taken

the

trouble

to

preserve

the

remains

of

its

small

Roman

civil

bath

house.

Still

clearly

visible in

situ are

tiles

stamped

'Leg

XX

VV'

and

bearing

the

wild

boar

motif

of

the

Twentieth

Legion.

(although,

by

the

summer

of

2001,

most

of

these

had

disappeared

and

this

site,

too,

became

subject

to

the

tender

attentions

of

the

property

developer,

as

you

may

read here).

Further

afield,

in Leicester, the

so-called Jewry

Wall is

the

largest

Roman

civil

building

surviving

in

Britain

and

formed

part

of

a great

public

baths

and

gymnasium

Bath, the famed Aqua Sulis of the Roman world, where visitors from around the globe queue to pay hefty fees to view the unrivalled bath house complex.

These

are

just

a few

examples.

Chester,

the

'Roman

City',

the

mighty

fortress

of Deva,

on

the

other

hand,

can

boast

of

little

like

this-

merely

the

make-believe

remnants

in

the

so-called Roman

Garden and

the

contents

of

a few

glass

cases

in

the

Grosvenor

Museum. In the 18th century, the enlightened citizens of Bath restored and re-opened their Roman bath house and the world flocked to see. In the 1960s, Chester bulldozed hers. Think of what might have been when you pass this way and look down from the wall into the car park below...

Half a century after the tragic destuction of the Roman bath house complex, a reproduction of the of the Ostia-style mosaics discovered there was created in late 2011 in the Roman Garden which we will be visiting shortly...

Trouble raised its head once again here in September 2007, when this stretch of City Wall was actually closed to the public for safety reasons. It seemed that a section of 18th century brick wall started to signs of collapse. It once formed the rear wall of an 18th stable block and was which unaccountably allowed to remain in place when this was demolished to make way for the precinct. Trouble raised its head once again here in September 2007, when this stretch of City Wall was actually closed to the public for safety reasons. It seemed that a section of 18th century brick wall started to signs of collapse. It once formed the rear wall of an 18th stable block and was which unaccountably allowed to remain in place when this was demolished to make way for the precinct.

Something of an almighty row had broken out regarding the state of our precious walls back in October 2006 when much hand wringing- not to mention a great deal of accusation and name-calling between political parties- ensued and a council working party reported that, much as they wished it otherwise, there simply wasn't enough money avilable to do the job properly and desperate appeals were said to be being made to central government to make up the shortfall.

The blame game stated again when this new problem arose. Athough the public was assured that the usafe structure did not actually form part of the ancient City Wall but merely butted up against it, great problems, it was reported, were being experienced ascertaining who exactly owned it- and would therefore be responsible for putting the matter right. It struck us, if not the local press, that ownership was no mystery. As the entire area belongs to the Duke of Westminster's Grosvenor Estate, and it was they who trashed the bath house complex and built the precinct, it seemed obvious that this humble wall must do too.

After safety tests, the city wall was re-opened to the public on Christmas Eve- but much more serious trouble was to follow a few months later in April 2008. Work had recently started on removing the troublesome brick wall when a great stretch of the ancient City Wall itself collapsed onto the recently-erected scaffolding! Our photograph, taken on 9th April, shows just a small part of the very serious destruction. It was a miracle that nobody was injured- people had been walking on the spot just moments earlier- but the entire stretch had now to be sealed off and signs erected directing visitors to a detour around the affected area.

It seems that the 'scaremongers' were right all along.

By the start of 2009, however, detailed archaeological and structural analysis of the damage had taken place- affording priceless insights into the wall's construction- and repairs were well under way. In the following December, the well-preserved remains of a previously-unknown Roman interval tower was discovered beneath the foundations of the City Wall. By the start of 2009, however, detailed archaeological and structural analysis of the damage had taken place- affording priceless insights into the wall's construction- and repairs were well under way. In the following December, the well-preserved remains of a previously-unknown Roman interval tower was discovered beneath the foundations of the City Wall.

These interval towers were sited at regular distances along the fortifications and acted as lookout points and as bases for artillery. They were constructed and placed according to the specifications of Roman military architects such as Marcus Vitruvius Pollio who directed that towers should be round, to deflect missiles and the force of battering rams, and placed so as to be within bow-shot of each other. He also directed that a wall should be of such a thickness that two armed men could pass on top of it without impediment.

Vitruvius's works were the standard reference on military and civil building principles from Roman times right up to the 18th century and his was the second book- after the Bible- to roll off the printing presses of Gutenberg. Read the whole of his great On Architecture on Bill Thayer's magnificent website here.

City Archaeologist Mike Morris said of the discovery: “We have been working closely with the stonemasons as they carefully dismantled the City Wall. When they came to the bottom, we excavated an archaeological trench to see what lay underneath. To our surprise, almost as soon as we started digging, a well-made sandstone wall appeared. It was running across the line of the City Wall and was more than 1m thick. Several of these towers have been found over the last hundred years and we knew there should be one in this vicinity but it is remarkable that we hit on exactly the right spot and that it has survived so well in this location. The last time we had the chance to investigate one of these was during the development at Abbey Green more than 30 years ago. Although we know a lot about the archaeology of Chester, there will always be exciting, unexpected discoveries like this. A tumble of large stones was found on each side of the Roman wall, probably from the collapse of the tower sometime after the fortress was abandoned and before the City Wall was built. It is hoped that these will be able to be reused in the rebuild so that something of this hidden history is visible for future generations.”

Restoration specialist Maysand undertook the repair work, joined by a team of specialists from Giffords, English Heritage, Chester Renaissance and Cheshire West and Chester Council. Visitors will be pleased to learn that all the repairs are now completed and the walkway along this section has re-opened, appearing to the casual observer as if nothing at all had ever happened...

Parallel

with

this

stretch

of

the

City

Wall, Newgate

Street formerly

ran

from

just

west

of

the

present Grosvenor

Hotel in

Eastgate

Street

to

the

Newgate.

From

the

12th

to

the

18th

centuries,

it

was

known

as Fleshmongers

Lane,

but

is

now

transformed, its antiquity suspected by few,

into Newgate

Row,

one

of

the

covered

ways

within

the

shopping centre

itself.

St. Michael's Street.

Our

photograph

above

shows

its

final

days

as

demolition

gangs

moved

in

to

prepare

the

ground

for

the

construction

of

the

precinct.

The Cathedral and

Eastgate

Street

may

be

seen

in

the

distance. In addition, our gallery of old photographs and drawings of Chester includes this interesting view of the precinct under construction in 1965.

A

concrete

walkway

on

our

right

allows

us

access,

should

we

so

desire,

to

the

car

park,

hotel

and

shops. A

little

further

on,

we

come

to

a

curious

structure

on

our

left.

This

is

a

14th

century

watchtower

known

as Thimbleby's Tower or The Wolf

Tower.

(seen under

the

small

triangular

roof

in

the

centre

of

our

photograph)

It

may

have

been

named

after

Sir

Richard

Thimblebye

of Hilbre

Island or

Lady

Thimbleby

who

died

in

Chester

in

1615.

It

originally

posessed

a

groined

roof

and

the

position

where

the

supports

joined

the

tower

may, with difficulty,

still

be

seen

within.

During

the

Civil

War Siege

of

Chester in

1645,

a

battery

of

cannon

under

the

command

of

Parlimentary

forces

was

situated

in

in

the

nearby

tower

of St. John's

Church.

After

some

fierce

firing,

the

Parliamentarians

attempted

to

scale

the

walls

using

ladders,

but

the

defenders

managed

to

beat

off

the

attack,

causing

many

casualties.

However,

by

that

time,

severe

damage

had

also

been

done

to

the

tower

and

the

upper

part

was

eventually

demolished,

never

to

be

rebuilt.

Later,

the

surviving

portion

was

used

as

a

laundry

by

the Kenrick

Family

whose

mansion

was

situated

nearby- and of whom more will will later be told-

and

it

also

later served

as

a

tile

kiln.

For

centuries,

the Wolf

Tower stood

open

to

the

sky

and

was

rather

a

sorry

sight,

generally

being

being

used

as

a

convenient receptacle

for

rubbish

thrown

from

the

wall.

Things

improved,

however, thanks

to the

city's

one-time

Conservation

Officer, Peter de Figueiredo.

As

part

of

his

'restoration'

of

the

tower,

a

strange,

historically

irrelevant,

new

roof

was

added

and

the

front

was

'enhanced'

with a crude wooden framework containing perspex windows

behind

which

was

provided

an

information

panel.

Within

a

very

short

time,

the

windows

had

been

vandalised,

the

panel

rendered

illegible

(and

subsequently

removed)

and

the

tower's

interior

rendered

virtually

impossible

to

view.

Thus,

despite

considerable

expenditure,

the

ancient

tower

has become

an embarrassment to all who love Chester's antiquities- and remains still

rather

a

'sorry

sight'. For

centuries,

the Wolf

Tower stood

open

to

the

sky

and

was

rather

a

sorry

sight,

generally

being

being

used

as

a

convenient receptacle

for

rubbish

thrown

from

the

wall.

Things

improved,

however, thanks

to the

city's

one-time

Conservation

Officer, Peter de Figueiredo.

As

part

of

his

'restoration'

of

the

tower,

a

strange,

historically

irrelevant,

new

roof

was

added

and

the

front

was

'enhanced'

with a crude wooden framework containing perspex windows

behind

which

was

provided

an

information

panel.

Within

a

very

short

time,

the

windows

had

been

vandalised,

the

panel

rendered

illegible

(and

subsequently

removed)

and

the

tower's

interior

rendered

virtually

impossible

to

view.

Thus,

despite

considerable

expenditure,

the

ancient

tower

has become

an embarrassment to all who love Chester's antiquities- and remains still

rather

a

'sorry

sight'.

On his own website De Figueiredo may describe himself as "one of the most experienced and knowledgeable professionals working in the field of historic building conservation" but, to many locals, an anagram of his name- 'eerie fidget doer-up'- succinctly sums up his brief career in Chester.

Left: the remains of the first-century Roman South-East Corner Tower and, beyond it, the medieval Thimbleby's Tower, clearly showing its absurd new roof.

The

wall

kinks

slightly

at

this

point

and

beneath

our

feet

we

see

the

predecessor

of

the

grander

entrance

which

stands

just

beyond

it.

This

is

the Peppergate or Wolfgate,

but

also

known,

after

a

rebuilding

in

1553,

as

the "Newegatt" ('Newgate). It

first

appears

in

the

written

record

as

the Porta

de

Wlfild c.1258

and

the

names Wulfeld

Gate or Woolfield

Gate were

later

used

until

a

shortened

version, Wolf

Gate,

became

common

in

the

15th

and

16th

From

the

11th

century,

there

was

a

community

of

Scandinavian

(Norse)

settlers

in

Chester-

their

settlements

were

common

throughout

the

Wirral

and

Merseyside

and

their

church,

dedicated

to

St. Olave,

still

exists

(and

recently

re-consecrated

after

years

of

being

used

for

more secular

purposes)

in

Lower

Bridge

Street.

The

gate's

name

may

be

connected

with

a

Scandinavian

personal

name

such

as

Ulf,

Ulfaldi,

Wulfadus,

or

the

like-

Interestingly,

the

son

of

Wulfhere,

King

of

Mercia,

and

brother

to St. Werburgh (to

whom

our

Cathedral

is

dedicated)

was

named Wulfhad,

so

'Wulfhad's

Gate'

may

have

possibly

been

a

monkish

dedication

to

this

Prince

and

martyr.

In

addition,

the

symbol

of

the

first

Norman

Earl

of

Chester,

Hugh

Lupus

('Hugh

the

Wolf'-

in

later

life,

'Hugh

the

Fat')

was

a

wolf's

head.

The

gate

took

one

of

its

names

from

the

street

that

passed

through

it,

known

from

at

least

the

13th

century

as Pepper

Street, and

having

never

changed

its

name

since

that

time.

From 1355: "Pepu Street goith out of Brugge Street apon the southe syde of the churche of Saynte Michell".

There

are

Pepper

Streets

in

other

ancient

English

towns,

for

example,

Middlewich,

Nantwich

and

Nottingham-

and

there

is

also

a Pepper

Alley in

Southwark,

London.

(from

where

Chaucer's

Canterbury

Pilgrims

set

out).

The

name

would

seem

to

mean

what

it

says-

referring

to

a

thoroughfare

redolent

of

pepper-

the

place

where

the

spice

merchants

practiced

their

trade.

Dodgson

comments: "It

is

likely

that

of

all

their

spices,

only

pepper

would

be

pungent

enough

to

be

discernible

through

the

stench

of

a

medieval

thoroughfare".

For many centuries a narrow lane, it was doubled in width to form part of Chester's Inner Ring Road during the 1960s. This interesting photograph by Chris Langford

shows Pepper Street- utterly devoid of charm- as seen from the Newgate just after the work had been completed. A little of how the street was in the eighteenth century may be imagined from the following advertisment in the long-defunct Chester Courant of December 4th 1750, "To be sold, a large and commodious dwelling-house with a coach-house, garden, summer-house and very good vaults, and other converniences proper for a gentleman's family, situate in Pepper-street, Chester, now in the holding of the Rev. Mr. Barnston".

The

Peppergate

was

originally

built

to

give

the

townsfolk

easier

access

to St. John's

Church just

outside

the

walls,

and

was,

for

defensive

reasons,

only

made

wide

enough

for

a

single

man

or

horse

to

pass

through

at

a

time-

in

fact,

a postern gate.

Of

Chester's

ancient

entrances,

only

the Kaleyard

Gate is

smaller.

It

was

however,

subsequently

enlarged

several

times:

in

1603,

1608

and

1768,

though

the

decorative mock

'battlements'

above

were

not

added

until

over

a

hundred

years

after

the

last

rebuilding.

'Shut

the

Peppergate' 'Shut

the

Peppergate'

There

is

an old

local

proverb

connected

with

this

gate

which

runs: "When

the

daughter

is

stolen,

shut

the

Peppergate".

About

the

year

1573,

the

daughter

of

a

Chester

Alderman,

Rauff

Aldersey,

despite

having

had

a

'suitable'

husband

chosen

for

her

by

her

father,

eloped

through

this

gate,

and,

to

quote

the

assembly

book

of

the

city, "was

married

by

an

unlawful

minister

to

one

Rauff

Iaman,

draper,

without

the

consent

and

goodwill

of

any

other

kinsfolk

and

friends,

to

their

great

heviness

and

grief,

and

contrary

to

any

good

civile

order".

So

incenced

was

her

influential

father

that

soon

after

he

persuaded

the

council

to

issue

the

order

that "for

divers

good

causes,

a

certain

gate

or

passage

through

the

walls,

called

Wolfe-gate

or

New-gate,

shall

forthwith

be

stopped

and

fenced

substancially

and

that

no

passage

to

be

suffered

in

the

nyght

and

the

same

to

be

opened

in

the

day". Thus,

'Shutting

the

Peppergate'

became

a

local

proverbial

equivalent

of

"Closing

the

stable

door

after

the

horse

has

bolted".

In

the

record

of

the

city's

expenses

for

the

year

1613,

is

the

following entry: "Paid

to

Stammering

Davye

for

clearing

the

watercourse

(gutter)

at

Newgate-

vi

d"

(sixpence).

The Kenrick Mansion

In 1748, while digging "very deep in Mr Kenrick's garden", a centurial stone was found. These were erected by units of the XXth Legion charged with building the fortress wall to record those sections for which they were responsible. The stone, now in the Grosvenor Museum, measures 24 by 6 inches and bears the following inscription: "The century of Ocratius Maximus, in the first cohort of the Legion built this piece of wall. L.M.P". (Limitis Mille Pedes: this denotes a length of wall equivalent to 1000 paces).

This garden was that of the barrister Andrew Kenrick, whose large mansion was built here on the eastern side of Newgate Street in 1703 on the site of seven cottages, their gardens and outbuildings. Described as being of brick with decorative stone facings, its lofty body was set back three yards between projecting wings and a flight of broad stone steps led to a front door on the first floor. On its southern side were stables and coach houses, stretching as far as, and butting onto, the Newgate. Behind it and on its northern side, extensive gardens stretched as far as Thimbleby's Tower, close to which the centurial stone was unearthed.

Such spacious elegance is difficult to imagine when we consider the jumbled collection of mediocre structures that later came to occupy the site.

The house's story is fascinating- but a sorry one indeed for its builder and his descendants. The land and cottages, which had been built around fifty years earlier, had passed through the hands of several families until it was eventually acquired by one Thomas Morris, who pursued a curious mix of professions- those of speculative builder and linen draper.

Hearing of the newly-married

barrister's search for a suitable property, Morris, himself lacking sufficient capital, borrowed heavily from several sources, demolished the cottages and proceeded to lay out a grand mansion, outbuildings and gardens on the site. Once completed, this was let to Kenrick at the sum of £24 per annum.

Trouble was soon to follow, however, as Morris soon found himself unable to repay the interest on his many loans, some of which were then settled by Kenrick. One of these was to John Hankey, whose widow, after he died unpaid, was arrested for debt, until Kenrick again stepped in to bail her out. The stress was evidently too much for her, however, for she died soon afterwards, in 1717.

By 1708, Kenrick himself, it transpired, had not paid any rent

for the last four years but he duly 'formalised' the situation by proposing to pay off some of the creditors from the owed money, rather than turn it over to Morris. Poor Thomas achieved little relief, however, for by 1712 he was resorting to earning a living as a 'cordwainer'- a shoemaker- and he eventually died, "being at the time very much indebted to many" in 1715. He left the sum of £15 to his wife, £30 as dowries to each of his two daughters- and the worry of his debts to his unfortunate son George. By 1708, Kenrick himself, it transpired, had not paid any rent

for the last four years but he duly 'formalised' the situation by proposing to pay off some of the creditors from the owed money, rather than turn it over to Morris. Poor Thomas achieved little relief, however, for by 1712 he was resorting to earning a living as a 'cordwainer'- a shoemaker- and he eventually died, "being at the time very much indebted to many" in 1715. He left the sum of £15 to his wife, £30 as dowries to each of his two daughters- and the worry of his debts to his unfortunate son George.

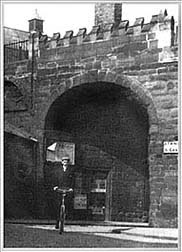

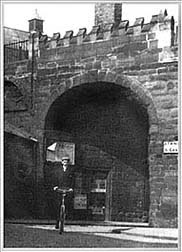

Right: the Wolfgate as it appeared in 1925, looking towards the site of the soon-to-be-discovered Roman amphitheatre.

George did his best to clear his father's numerous debts. He declared himself perfectly willing to dispose of his father's estate in order to do so but its value was considerably less than the sums owed and he was eventually arrested as a debtor and imprisoned in the infamous Northgate gaol, where he stayed until one of his sisters, who had recently married a Mr Seagreen and moved to London, was persuaded, with her new husband's agreement, to give up her £30 dowry in order to secure his release. Freed in 1718, George soon after turned over the Newgate Street mansion, "together with the coach-house, two stables, beere-house, the yard, coal-yard, muck-yard and two gardens" to Andrew Kenrick, who by this time had become widowed and married for a second time, for the princely sum of £510.

The course of poor George's life from this point on is unknown but we can only earnestly hope that, at last, fortune started to smile on him...

Andrew Kenrick, his new wife and children long continued to enjoy their occupation of the mansion and eventually acquired Thimbleby's Tower (which we met with earlier) which they converted for use as a laundry and even obtained permission to make a passage through the City walls to allow easy access from their garden to the tower. Andrew died, having achieved the high office of Vice-Justice of Chester, in 1747 and several generations of his descendants lived and died in the house and were buried with him in nearby St. John's Church.

The Kenricks

had originally hailed from Woore in Shropshire, where they owned property and maintained a house, Woore Manor. They also possessed land in North Wales. Before bidding them farewell, there is one last tale concerning them that may explain why young Andrew was so anxious to leave the ancestral lands and set up home in Chester instead.

One of their other properies in the village, Woore House- now a farmhouse- was the scene of a grim tragedy, for, at an unrecorded point in the recent past, one of the daughters of the house was murdered by her brother, in pursuit of the money she possessed. It was said by the villagers that the place was afterwards haunted by poor Miss Kenrick's ghost and that a portion of the cellar had been closed off immediately after the event and never re-opened. It was said that in the cellar was a table with a bottle upon it, so it may perhaps be inferred that the murder took place with poison and that the body was hidden here... One of their other properies in the village, Woore House- now a farmhouse- was the scene of a grim tragedy, for, at an unrecorded point in the recent past, one of the daughters of the house was murdered by her brother, in pursuit of the money she possessed. It was said by the villagers that the place was afterwards haunted by poor Miss Kenrick's ghost and that a portion of the cellar had been closed off immediately after the event and never re-opened. It was said that in the cellar was a table with a bottle upon it, so it may perhaps be inferred that the murder took place with poison and that the body was hidden here...

In the early 19th century, the house passed to the Farmer family, one of whom became a noted Royal Navy captain- Horatio Nelson served as a midshipman under him. It then, in the 1870s, passed on to the Boydells, under whom the estate was split up and in the 1920s the mansion, described in a Cheshire Sheaf of the day as a 'quaint, old, ivy-covered, gabled house" became the home of the noted family of veterinary surgeons, the Storrars, who continue in that noble profession in Chester to this day.

At

this

point,

the

original

Roman

South

Wall

turned

west,

roughly

following

the

line

of

the

righ-hand

side

of

Pepper

Street,

and

below

us

we

can

see

the

excavated

lower

courses

of

this

ancient

wall,

together

with

its

internal South East

Corner

Tower (illustrated

above)

dating,

according

to

Professor

Newstead,

from

the

earliest

days

of

the

stone

fortress-

around

81-96

AD,

in

the

reign

of

the

Emperor

Domitian.

It

is

the

only

one

of

the

twenty

six

Roman

towers

known

to

have

existed

whose

remains

have

been

put

on

public

display.

Prof Newstead

wrote

at

the

time, "In

contrast

with

the

North

Wall

and

north

part

of

the

East

Wall

which

were

rebuilt

early

in

the

third

century....the

south-east

portion

remained

in

use

until

the

end

of

the

Roman

occupation" (around

400

years) "The

remains

exhibited

an

element

of

great

permanency

throughout:

there

was

no

trace

of

structural

alterations

or

rebuilding...

moreover

there

was

no

trace

of

a

conflagration

or

the

like.

The

mutilations

we

see

today...

are

evidently

the

work

of

medieval

builders

who

quarried

the

ready-made

blocks

of

sandstone

and

re-used

them

in

their

temples

and

defensive

walls".

For centuries lost beneath later buildings,

the

remains

of

the

ancient tower, now set within a small but pleasing

garden, was

opened

to the public in

1949.

In common with many places in Chester, there is a ghostly yarn connected with this place. A Roman section leader who served here who was in the habit of leaving his men on duty to have an amorous dalliance with a local British girl on the banks of the River. Returning one night he found all his men dead, slain by local tribesmen. Faced with the choice of death or dishonour he chose the former and flung himself off the tower. People are said to see his forlorn ghost walking between the river and the remains of the tower, via Souters Lane.

The

Victorian

writer Joseph

Hemingway,

normally

an

entertaining

and

reliable

Chester

guide,

got

it

badly

wrong

regarding

the

Saxon

extension

of

the

walls- which commence at this point-

when

he

asserted: "The

present

form

of

the

walls

is strictly

Roman,

which

goes

a

great

way

to

negative

the

old

legends

of

the

monkish

chronicles,

that

the

walls

were

enlarged

one-third

in

circumference

by

Ethelfleda,

the

celebrated

Saxon

princess.

The

walls

at

present... are

so

entirely

Roman,

that

any

addition

she

could

make

would

have

destroyed

the

peculiar

figure

which

that

wise

people

always

preserved

in

their

stations,

wherever

the

the

nature

of

the

ground

would

permit".

Refer again to our sketch map of Chester's City Walls to compare the area of the original Roman fortress with the later Saxon and Norman extensions. Refer again to our sketch map of Chester's City Walls to compare the area of the original Roman fortress with the later Saxon and Norman extensions.

The

imposing modern

structure

bearing

a

proud

stone

lion

on

its

roof

seen

on

the

corner

of

Pepper

Street

and

Park

Street

is

a

multi-storey

car

park

which was designed by the Biggins Sergent Partnership. It

stands

on

the

site

of

the Lion

Brewery,

which

was

established

here

in

1642.

It

was

said

that

underneath

it

was

a

tunnel

used

to

sally

the

besiegers

during

the

Civil

War. The

brewery

was

rebuilt

in

1875

by

Bent's

and

the

lion,

their

trademark,

was

added

at

this

time.

It was made of a manmade material called coadstone. When

the

building

was

eventually

demolished

and

replaced

with

the

starkly

modern

structure,

the

lion

was

saved

by

the secretary of the Chester

Civic

Trust, Dr John Tomlinson, and displayed fror a while in his garden in Curzon Park before being

remounted

on

the

top

of

its tall

lift shaft.

You can see a fine photograph of the Newgate and Lion Brewery here, part of our 'lost pubs, hotels and breweries' gallery.

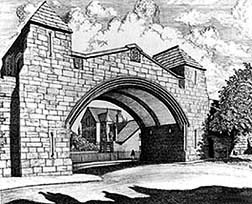

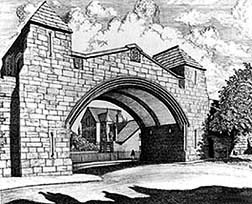

A

few

steps

on

and

we

come

to

the Newgate,

seen

here

in

a

fine

drawing

made

in

1939

by

William

Robert

Wright

Boyd. Its playful design puts one in mind of the set of a Hollywood production of Robin Hood or suchlike 'Merry

England' swashbuckler...

Despite appearances, the Newgate is actually built

of reinforced concrete and faced with red Runcorn sandstone. The architect was Sir Walter Tapper, who died before its completion, the work- which took a mere

20 months- being completed by his son, Michael Tapper.

(Sir Walter (1861-1935) was best known known for his Gothic Revivalist architecture. Learn more about the man and his work on John Whitworth's website: Sir Walter Taller and his Churches.)

Through the arch may be seen Victorian extension to Dee House, which

had originally been built in 1730 over the south-west quarter of the Roman amphitheatre-

at the time of writing, the future of Dee House and the amphitheatre are a subject

of great local controversy, as we shall soon see. Through the arch may be seen Victorian extension to Dee House, which

had originally been built in 1730 over the south-west quarter of the Roman amphitheatre-

at the time of writing, the future of Dee House and the amphitheatre are a subject

of great local controversy, as we shall soon see.

With the coming of the motor car, the old Wolfgate proved completely inadequate

so this new entrance was built in a cheerful mock-medieval style (more correctly

described as Gothic Revival) and opened by the Mayor on October 3rd 1938. There was considerable debate at the time regarding how this new entrance through the City Walls was to be executed, even with the pages of the national press. This article, for example, appeared in the London Times on 27th April 1929:

"The necessity for sacrificing about 40ft. of the old city wall at Chester to the needs of modern traffic has led to a controversy concerning the type of bridge which shall be constructed across the widened gap to carry the footway by which visitors walk round the walls. One side proposes a mock-medieval archway, possibly with lesser archways for the pavements, all in the Gothic style. The other, led by the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, argues that the needs would be met by an unpretentions bridge of iron, made perhaps in the Adam style. As Chester's walls are scheduled as an ancient monument, the Chester Corporation, which has the street-widening project in hand, has been brought into conference with the authorities in London and has finally accepted the suggestion that the Royal Institute of British Architects should be asked to prepare a design for its consideration.

That, however, does not necessarily indicate an agreement in principle as to the treatment the case is unanimous. The trouble has arisen owing to the serious traffic congestion caused at the Cross by the narrowness of the New Gate. This gate was cut through the walls in the the 18th century (oops!), and allows only a single line of traffic to pass. It has been shown that the traffic difficulty cannot be solved except by widening this gate at the cost of some 40ft. of wall or by another scheme which would involve damage to the Rows, those quaint medieval galleries of shops, and the destruction of St. Peter's Church. There has, therefore, been no serious opposition to the widening of the New Gate. The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings agreed that it was the right course, and its criticism was only evoked when certain archaeological architects proposed that over the widened gateway should be thrown a great archway, with lesser ones on either side to cover the pavements. This scheme was regarded as a mistake and as an alternative it was suggested that two fairly big piers should be built on either side of the gate in order to end off the walls suitably and that nothing should be carried over the roadway except a light ironwork bridge, for the purely utilitarian purpose of conecting up the footways running round the walls on either side". That, however, does not necessarily indicate an agreement in principle as to the treatment the case is unanimous. The trouble has arisen owing to the serious traffic congestion caused at the Cross by the narrowness of the New Gate. This gate was cut through the walls in the the 18th century (oops!), and allows only a single line of traffic to pass. It has been shown that the traffic difficulty cannot be solved except by widening this gate at the cost of some 40ft. of wall or by another scheme which would involve damage to the Rows, those quaint medieval galleries of shops, and the destruction of St. Peter's Church. There has, therefore, been no serious opposition to the widening of the New Gate. The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings agreed that it was the right course, and its criticism was only evoked when certain archaeological architects proposed that over the widened gateway should be thrown a great archway, with lesser ones on either side to cover the pavements. This scheme was regarded as a mistake and as an alternative it was suggested that two fairly big piers should be built on either side of the gate in order to end off the walls suitably and that nothing should be carried over the roadway except a light ironwork bridge, for the purely utilitarian purpose of conecting up the footways running round the walls on either side".

The design of the new gateway was eventually settled and it was opened on 3rd October 1938. This report appeared in The Times the following day:

"The rebuilt Newgate at Chester was opened by the Mayor, Alderman George Barlow, yesterday. Presenting the Mayor with a pair of gold scissors with which to cut the tape, Alderman Matthew Jones suggested that they might rename it the Munich Gateway having regard to the circumstances of its inauguration. A prayer was offered by the Dean of Chester, and afterwards there was a luncheon at the Town Hall. The gate has been erected to meet traffic demands and displaces the oldest of the city's gates. The date of erection of the original gate is not known, but a gate stood on the present site in or before 1327 and was known as Wolf's Gate, and later as Pepper Gate".

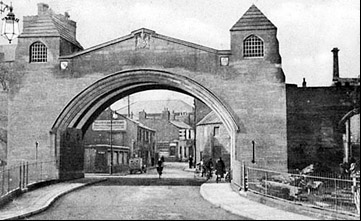

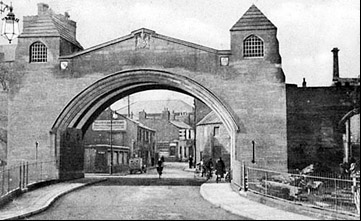

Above is a rare photograph of the Wolfgate still in

use by motor traffic- and demonstrating its increasing unsuitability for such- while the wall next to it is being torn down to make way

for the grand new entrance. The council had planned to carry a new road straight ahead

from this gate- right across a site unfortunately occupied by the newly-discovered

Roman amphitheatre! National uproar naturally ensued, and the Ministry of Works eventually compelled

them to construct their road around the ancient monument instead. Sadly, the foolishness did not end there, as we are about to discover in the course of our next few chapters. Above is a rare photograph of the Wolfgate still in

use by motor traffic- and demonstrating its increasing unsuitability for such- while the wall next to it is being torn down to make way

for the grand new entrance. The council had planned to carry a new road straight ahead

from this gate- right across a site unfortunately occupied by the newly-discovered

Roman amphitheatre! National uproar naturally ensued, and the Ministry of Works eventually compelled

them to construct their road around the ancient monument instead. Sadly, the foolishness did not end there, as we are about to discover in the course of our next few chapters.

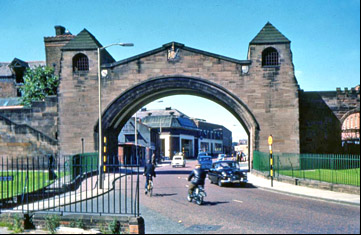

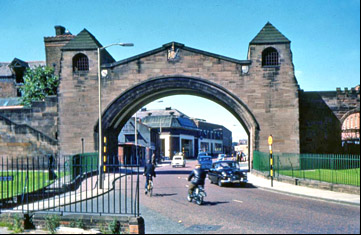

Above right we see the newly-completed Newgate in 1938- the little corner tower park next to it is still unfinished. Note how narrow Pepper Street still is, and will remain for some decades, until the coming of the Inner Ring Road. The tower of the Lion Brewery may be seen rising on the left.

On the left, we see the same view thirty years later. The road has been widened and new buildings have risen but the old brewery still, for the moment, stands. Aside from the latter- and a radical increase in traffic- the scene looks almost exactly trhe same today.

In early 2011 a plan came to light, sponsored by Cheshire West & Chester Council and Chester Renaissance, to construct

a modern steel structure on top of the Newgate, a viewing platform "designed to provide improved views of the Roman surroundings, including the amphitheatre." The proposals were, inevitably, backed by 'conservation specialists' and English Heritage.

Objections to the plans soon followed, saying that the development was grossly inappropriate to Chester's City Walls, that it was unnecessary- and aptly describing the proposed structure as "a perforated baked bean tin".

Somewhat embarrassingly, in early March 2011, CWAC's own councillors unanimously rejected the planning application. Only time will tell if it will rear its ugly head in modified form.. Watch this space.

From our vantage point on top of the Newgate we can see outside the walls a very special- and very threatened- relic of Chester's ancient past, which we are to visit next. Brace yourselves....

Curiosities from Chester's History no. 12

- 1540 The Mayor of Chester, Henry Gee, made an order that no female between the ages

of 14 and 40 years were to to be allowed to serve in or keep any inn or tavern.

Also that all children over 6 years old should attend school every work day,

and on Sundays and Holy days and after attending church they must exercise

with bows and arrows on the Roodee or other

open spaces. He also ordered that unmarried women should not be permitted

to wear white or coloured caps, and no woman to wear any hat unless when riding

or when she 'goe abroad into the country" on pain of a fine of 3s 4d. King

Henry

VIII marries Anne of Cleves. The marriage is annulled and he marries Catherine

Howard.

- 1536-1541 The Dissolution of the Monasteries. In 1541 Letters Patent decreed that an

episcopal see and Cathedral Church be

founded on the site of the dissolved Benedictine Monastery of St. Werburgh,

and that Chester should forever be a city, exempt from the jurisdiction of

the Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield. John Bird was appointed Bishop and Thomas

Clark appointed Dean of the new Cathedral. St Mary's Nunnery surrendered. The King's School was founded by

Henry VIII. Ordered, that when any of the common council die, others shall

be chosen in their places, of the 'saddest and most substantial citizens'.

'Sturdy beggars' ordered to be 'whipped at the cart's tail' and, if caught begging

for a third time, to be executed.

- 1540 First horse races on the Roodee.

- 1542 Queen Catherine Howard, Henry's fifth wife, executed after less than two years of marriage for 'immoral conduct'. Mary, Queen

of Scots (1542-1587) comes to the Scottish throne, aged six days.

- 1543 Henry VIII marries Catherine Parr, his sixth wife- who survives him

- 1547 Henry VIII died, his and Jane Seymour's son, Edward VI (1537-1553) ascended the

English throne, aged nine years. The 'Holy Rood' (the figure of Christ on the Cross) taken

down from St. Mary's-on-the-Hill and the walls were whitelimed to destroy any

paintings or ornamentation which were upon them. St Ursula's Hospital dissolved, but continues as Sir Thomas Smith's Almshouses.

- 1548 Edward VI's commissioners visited St. John's,

which at the time was a Collegiate church with a Dean and seven Canons. It

was acknowledged that the congregation had the right to worship in the Nave,

which was consequently spared, but the Choir and Chantry Chapels were dismantled- "the goods and ornaments, plate and jewels" and all but a single bell, were

all taken for the King's use.

- 1550 An abundance of tallow having been brought into the city, it was ordered

that candles should be sold "at a fair price" of threepence ha'penny a pound.

The 'sweating sickness' returned to Chester, one victim of which was Edmund

Gee, the zealously reforming Mayor. John Speed wrote of its effect upon the country, "wherein died infinite numbers of men

in their best strength which followed onely Englishmen in forraine countreys,

no other people infected therewith, whereby they were both feared and shunned

in all places where they came." First licencing of alehouses and taverns in

England and Wales.

- 1553 Edward VI dies; Lady Jane Grey proclaimed Queen of England,

but is deposed nine days later and executed. Mary I, ('Bloody Mary' 1515-1568) daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine

of Aragon, becomes Queen.

- 1554 Lady Jane Grey executed; Princess Elizabeth sent to

the Tower for suspected participation in rebellion against Queen Mary- who

marries Philip II of Spain the same year. George Marsh (1515-1555), a Protestant Minister,

after being tried in the Lady Chapel of the Cathedral, was burnt at

the stake at Boughton for "blasphemous

and heretical preaching against the Pope and Church of Rome." On April 24th

he was marched through the streets of Chester to Boughton, reading his Bible

on the way. He was offered a pardon if he would recant, but refused to do

so and consequently perished in the flames. The fire, it is said, was badly managed and his death "protracted".

|

hould

you

be

overcome

with

the

urge

to

go

shopping,

you

can

join

Eastgate

and

Foregate

Streets

by

descending

the

steps

on either

side

of

the

Eastgate.

Otherwise,

we

shall

cheerfully

leave

the

commercial

bustle

behind

us

and

continue

on

our

way.

hould

you

be

overcome

with

the

urge

to

go

shopping,

you

can

join

Eastgate

and

Foregate

Streets

by

descending

the

steps

on either

side

of

the

Eastgate.

Otherwise,

we

shall

cheerfully

leave

the

commercial

bustle

behind

us

and

continue

on

our

way. Could things possibly get worse? Indeed they could-

on the site of Hughes' "unpicturesque buildings",

beyond

a shabby

bit

of

wooden

fencing

now rises

the

crude

bulk

of

the Grosvenor

Laing Precinct and

its

even

uglier multi-storey

car

park,

opened

in

1971

and

an

outstanding

example

of

the

brutalist

architecture

of

the

period.

Could things possibly get worse? Indeed they could-

on the site of Hughes' "unpicturesque buildings",

beyond

a shabby

bit

of

wooden

fencing

now rises

the

crude

bulk

of

the Grosvenor

Laing Precinct and

its

even

uglier multi-storey

car

park,

opened

in

1971

and

an

outstanding

example

of

the

brutalist

architecture

of

the

period.  If

only

that

had

proved

to

be

the

case.

The (now defunct) Cheshire

Observer of

5th

September

1969

quoted

the

Oxford

Professor

of

the

Architecture

of

the

Roman

Empire, Professor

S S

Frere,

then

on

a visit

to

Chester,

as

saying, "It is absolutely disgraceful that modern businesses cannot see the value of

the history of the town where they have their businesses and which they are

expoiting".

If

only

that

had

proved

to

be

the

case.

The (now defunct) Cheshire

Observer of

5th

September

1969

quoted

the

Oxford

Professor

of

the

Architecture

of

the

Roman

Empire, Professor

S S

Frere,

then

on

a visit

to

Chester,

as

saying, "It is absolutely disgraceful that modern businesses cannot see the value of

the history of the town where they have their businesses and which they are

expoiting".

During

demolition

and

site

clearance

work,

the

rear

of

St. Michael's

Arcade

was

sealed

off

by

a wooden

hoarding,

into

which

was

thoughtfully

inserted

a number

of

windows

through

which

the people of Chester

could,

in

the

words

of

eminent archaeologist Dr.

David

Mason, "watch

their

precious

Roman

heritage

being

smashed

up

and

carted

away

on

the

backs

of

lorries" (Roman

Chester:

City

of

the

Eagles,

p. 20).

He knew whereof he spoke for he records in this excellent book how, as a boy, he was one such observer.

During

demolition

and

site

clearance

work,

the

rear

of

St. Michael's

Arcade

was

sealed

off

by

a wooden

hoarding,

into

which

was

thoughtfully

inserted

a number

of

windows

through

which

the people of Chester

could,

in

the

words

of

eminent archaeologist Dr.

David

Mason, "watch

their

precious

Roman

heritage

being

smashed

up

and

carted

away

on

the

backs

of

lorries" (Roman

Chester:

City

of

the

Eagles,

p. 20).

He knew whereof he spoke for he records in this excellent book how, as a boy, he was one such observer.

By 1708, Kenrick himself, it transpired, had not paid any rent

for the last four years but he duly 'formalised' the situation by proposing to pay off some of the creditors from the owed money, rather than turn it over to Morris. Poor Thomas achieved little relief, however, for by 1712 he was resorting to earning a living as a 'cordwainer'- a shoemaker- and he eventually died, "being at the time very much indebted to many" in 1715. He left the sum of £15 to his wife, £30 as dowries to each of his two daughters- and the worry of his debts to his unfortunate son George.

By 1708, Kenrick himself, it transpired, had not paid any rent

for the last four years but he duly 'formalised' the situation by proposing to pay off some of the creditors from the owed money, rather than turn it over to Morris. Poor Thomas achieved little relief, however, for by 1712 he was resorting to earning a living as a 'cordwainer'- a shoemaker- and he eventually died, "being at the time very much indebted to many" in 1715. He left the sum of £15 to his wife, £30 as dowries to each of his two daughters- and the worry of his debts to his unfortunate son George.

Refer again to our

Refer again to our  Through the arch may be seen Victorian extension to

Through the arch may be seen Victorian extension to  That, however, does not necessarily indicate an agreement in principle as to the treatment the case is unanimous. The trouble has arisen owing to the serious traffic congestion caused at the Cross by the narrowness of the New Gate. This gate was cut through the walls in the the 18th century (oops!), and allows only a single line of traffic to pass. It has been shown that the traffic difficulty cannot be solved except by widening this gate at the cost of some 40ft. of wall or by another scheme which would involve damage to the Rows, those quaint medieval galleries of shops, and the destruction of St. Peter's Church. There has, therefore, been no serious opposition to the widening of the New Gate. The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings agreed that it was the right course, and its criticism was only evoked when certain archaeological architects proposed that over the widened gateway should be thrown a great archway, with lesser ones on either side to cover the pavements. This scheme was regarded as a mistake and as an alternative it was suggested that two fairly big piers should be built on either side of the gate in order to end off the walls suitably and that nothing should be carried over the roadway except a light ironwork bridge, for the purely utilitarian purpose of conecting up the footways running round the walls on either side".

That, however, does not necessarily indicate an agreement in principle as to the treatment the case is unanimous. The trouble has arisen owing to the serious traffic congestion caused at the Cross by the narrowness of the New Gate. This gate was cut through the walls in the the 18th century (oops!), and allows only a single line of traffic to pass. It has been shown that the traffic difficulty cannot be solved except by widening this gate at the cost of some 40ft. of wall or by another scheme which would involve damage to the Rows, those quaint medieval galleries of shops, and the destruction of St. Peter's Church. There has, therefore, been no serious opposition to the widening of the New Gate. The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings agreed that it was the right course, and its criticism was only evoked when certain archaeological architects proposed that over the widened gateway should be thrown a great archway, with lesser ones on either side to cover the pavements. This scheme was regarded as a mistake and as an alternative it was suggested that two fairly big piers should be built on either side of the gate in order to end off the walls suitably and that nothing should be carried over the roadway except a light ironwork bridge, for the purely utilitarian purpose of conecting up the footways running round the walls on either side".

Above is a rare photograph of the Wolfgate still in

use by motor traffic- and demonstrating its increasing unsuitability for such- while the wall next to it is being torn down to make way

for the grand new entrance. The council had planned to carry a new road straight ahead

from this gate- right across a site unfortunately occupied by the newly-discovered

Roman amphitheatre! National uproar naturally ensued, and the Ministry of Works eventually compelled

them to construct their road around the ancient monument instead. Sadly, the foolishness did not end there, as we are about to discover in the course of our next few chapters.

Above is a rare photograph of the Wolfgate still in

use by motor traffic- and demonstrating its increasing unsuitability for such- while the wall next to it is being torn down to make way

for the grand new entrance. The council had planned to carry a new road straight ahead

from this gate- right across a site unfortunately occupied by the newly-discovered

Roman amphitheatre! National uproar naturally ensued, and the Ministry of Works eventually compelled

them to construct their road around the ancient monument instead. Sadly, the foolishness did not end there, as we are about to discover in the course of our next few chapters.