fter

our

tour

of

of

the Cathedral,

we

will

now

rejoin

the

City Walls

and

wander

on. You

will

hardly

fail

to

notice

a distinctive

tall

modern structure

situated

in the corner of the churchyard here.

This

free-standing bell tower

or campanile is

known

as

the Addleshaw

Tower,

after

its

commissioner,

Dean

Addleshaw.

It

was

built

to accomodate the Cathedral's bells after

the

decaying bell frame in the

15th

century

central

tower

began

to

show

signs

of

stress

and

judged

no

longer

capable

of

supporting

their

great

weight. fter

our

tour

of

of

the Cathedral,

we

will

now

rejoin

the

City Walls

and

wander

on. You

will

hardly

fail

to

notice

a distinctive

tall

modern structure

situated

in the corner of the churchyard here.

This

free-standing bell tower

or campanile is

known

as

the Addleshaw

Tower,

after

its

commissioner,

Dean

Addleshaw.

It

was

built

to accomodate the Cathedral's bells after

the

decaying bell frame in the

15th

century

central

tower

began

to

show

signs

of

stress

and

judged

no

longer

capable

of

supporting

their

great

weight.

Looking rather like a windmill without sails, it was designed,

by no means

to

everyone's

taste,

by the architect to York Minster, George

Pace (1915–1975) and

completed

in

1974. It

is

the

first

free-standing

bell tower

built

for

a

cathedral

since

that of Chichester in the

15th

century.

Constructed

of

concrete

with

brick

infilling and covered with slates from the mines of Penrhyn in North Wales,

the tower

stands

86

feet

high

and

houses

thirteen

bells. The

great

Tenor

Bell

is

named

after

Christ

and

Our

Lady,

to

whom,

along

with

St. Werburgh,

the

Cathedral

is

dedicated.

It

weighs

24.75

cwt,

and

is

4ft

4ins

in

diameter.

As we learned in the last of our Cathedral chapters, the Dean & Chapter and local authority are currently planning a range of controversial 'improvements' to the environment of the churchyard, including, we hear, the addition of a cafe in the base of the Addleshaw Tower.

The world's most famous campanile is, of course, the Leaning Tower of Pisa. To learn more about the bells of Chester and those who ring them, be sure to read Ringing in Chester by Phil Burton, here. His site offers some fascinating insights into the bellringer's art and also some nice photographs of other Chester churches. The world's most famous campanile is, of course, the Leaning Tower of Pisa. To learn more about the bells of Chester and those who ring them, be sure to read Ringing in Chester by Phil Burton, here. His site offers some fascinating insights into the bellringer's art and also some nice photographs of other Chester churches.

A

flight

of

stone

steps,

which

were

erected

in

1931

at

a

cost

of £288,

here

descend

to

an

attractive,

tree lined- but

slightly

scruffy-

area

now

used

mainly

for

car

parking,

which

has

for

centuries

gone

under

the

name

of The Kaleyards,

due

to

the

fact

that

the

vegetable

gardens

of

the

monks

of

Chester

Abbey

were

once located

here.

If

you

look

down

from

the

wall,

you

will

see

the

semi-circular

base

of

the

vanished

thirteenth-century Drum

Tower, which

had

formerly

been

used

by

the

Barber's

Company,

who

exercised

most

of

the

functions

of

physicians

and

surgeons.

Between

here

and

the Phoenix

Tower also once stood

the Sadler's

Tower until

it

was

demolished

in

1779

after

falling

into

decay.

It

had

risen

20

feet

above

the

walkway

and

contained

rooms

with

groined

roofs.

Over

its

doorway

was

a 'machicolation' for

pouring

boiling

oil,

lead

or

suchlike,

onto

the

heads

of

unwary attackers.

The

Sadler's

guild

used

the

tower

for

their

meetings,

and

paid

four

shillings

per

year

rent

for

it

in

the

sixteenth

century. We

learned

while

visiting The Kaleyards that

the

tower

was

eventually

demolished

and

the

last

traces

of

it

were

removed

when

this

section

of

wall

was

rebuilt

in

the

1820s.

The

whole

area

before

us

was

for

centuries

open

ground

and

was

utilised

by

the

Roman

garrison

as

a

parade

ground.

Below

us,

the

masive

stones

that

comprised

part

of

their

fortress

wall

are

clearly

visible,

and

may

be

closely

inspected

from

the

car

park

below.

The

road

beyond,

today's Frodsham

Street, was

once

the

commencement

of

a

Roman

road

which

ran

from just outside

the

main entrance to the fortress,

along

the

line

of

modern

Brook

Street,

through

what is now the

pleasant suburb

of

Hoole

(where

these

words

are

being

written)-

and

on

to

Frodsham

and

Warrington.

Much

of

the

route

remains

in

use

to

this

day-

although

some

sections,

as

at

the 'Newton

Hollows' in

Hoole,

are

now

little

more

than

footpaths.

If we may briefly digress from our current route, when landscaping work was undertaken at the Newton Hollows a few years ago, the council website had this to say about them,

"Newton Hollows is a rare and fascinating archaeological survival located in surburban Chester...an ancient route from Wilderspool into Chester. Originally a Roman road it was later used as a main route for people, cattle, and herds of sheep. This constant passage of trafficking over 1000 years has physically shaped The Hollows. (Note that 'Hoole' translates as 'Hollows' registered 1190AD)

It remained in use as the main route from Chester to the north until it was abandoned in the 18th century when a turnpike road was constructed on the line of Hoole Road.

In the mid 12th century it appears to have been known as 'The Valley of the Demons', perhaps with reference to the hiding place of robbers and thieves lying in wait for unsuspecting travellers. In addition, legend has it that the hollow was haunted, and travellers had to run the risk of coming across 'The Hound of Hell’ with reported sightings of a huge black, slavering dog with ‘great white teeth like knives’. It is a superb example of a medieval hollow way, though this is hard to tell due to the volume of trees and undergrowth"...

Resuming our stroll, in

the

middle

ages

the

area

before

us

was

known

as

the Jousting

Croft,

where

jousts

and

tournaments

were

held

and

games

of

all

kinds

were

played. All

round

the

perimeter

would

be

erected

the

stalls,

booths

and

amusements

of

the

fairs

and

markets

and

it

was

to

this

stretch

of

wall

that

the

townsfolk

and

visitors

flocked

to

gain

a

grandstand

view

of

the

crowds

below

at

what

must

have

been

exciting

and

colourful

occasions: Resuming our stroll, in

the

middle

ages

the

area

before

us

was

known

as

the Jousting

Croft,

where

jousts

and

tournaments

were

held

and

games

of

all

kinds

were

played. All

round

the

perimeter

would

be

erected

the

stalls,

booths

and

amusements

of

the

fairs

and

markets

and

it

was

to

this

stretch

of

wall

that

the

townsfolk

and

visitors

flocked

to

gain

a

grandstand

view

of

the

crowds

below

at

what

must

have

been

exciting

and

colourful

occasions:

"The

plain... was

a

forest

of

pavillions,

every

colour

of

the

rainbow...

Then

there

were

the

people

themselves.

All

around

and

about

the

tents

there

were

cooks

quarreling

with

dogs

who

had

eaten

the

mutton,

and

small

pages

writing

insults

on

each

other's

backs

when

they

were

not

looking,

and

elegant

minstrels

with

lutes

singing

tunes

similar

to

'Greensleeves'

with

soulful

expressions,

and

squires

with

a

world

of

innocence

in

their

eyes,

trying

to

sell

each

other

spavined

horses,

and

hurdy-gurdy

men

trying

to

earn

a

groat

by

playing

on

the

vielle,

and

gypsies

telling

your

fortune,

and

enormous

knights

with

their

heads

wrapped

in

untidy

turbans

playing

chess

and-

as

for

entertainment-

there

were

joculators,

gleemen,

tumblers,

harpers,

troubadours,

jesters,

minstrels,

tregetours,

bear-dancers,

egg-dancers,

ladder-dancers,

ballet

dancers,

montebanks,

fire-eaters

and

balancers..."

T H White: The

Once

and

Future King

For nearly two centuries the site has been hemmed in by a conglomeration of houses, shops and other buildings, but as late as 1705, the prospect of this area from the City Walls was very different, and was then described as "a meadow, on the other side of the Gale-yards and Cow Lane, anciently, and now called the Justing Croft, wherein tilt and tourney were heretofore practised- a place very proper for these military exercises, both for the combatants, the ground not being over hard, and the spectators, who from the Walls, and from the houses adjoining on the one side, and the gently ascending grounds on the other, might with security and pleasure see the whole of the performance". For nearly two centuries the site has been hemmed in by a conglomeration of houses, shops and other buildings, but as late as 1705, the prospect of this area from the City Walls was very different, and was then described as "a meadow, on the other side of the Gale-yards and Cow Lane, anciently, and now called the Justing Croft, wherein tilt and tourney were heretofore practised- a place very proper for these military exercises, both for the combatants, the ground not being over hard, and the spectators, who from the Walls, and from the houses adjoining on the one side, and the gently ascending grounds on the other, might with security and pleasure see the whole of the performance".

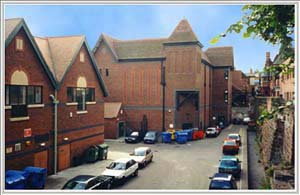

Left: a wonderful prospect of Chester Cathedral from the entrance to the Kaleyards from Frodsham Street. This view would be utterly ruined should the council's plan to build a new Market Hall here ever be realised..

Little relating to the specific contests that took place upon this ground has come to light, but an event alluded to in the 12th century by Lucian the Monk may be one. He related that, a few years before he wrote, there emerged from the City Walls a crowd of all ages, sexes and ranks, so vast in size that scarcely a wretched old woman remained at home. The occasion for this exodus was a contest between two armed horsemen in a certain level piece of ground in the presence of the king's son and a peer of the realm- a combat in which, Lucian congratulates his readers or auditors, the Englishman won. This event appears to have taken place in the year 1186 when Prince John, son of King Henry II, and Philip of Worcester, were waiting to take ship for Ireland. Lucian did not record exactly where this contest took place and the Roodee is an alternative, but unlikely site as, prior to the erection of the embankment or 'cop' in 1587, it was boggy ground, still largely covered with water.

It was probably about the close of the sixteenth century that these military exercises ceased to be performed. The Shropshire Union Canal now flows through the old Jousting Croft and part of Queen Street covers the south side of it today.

Archery practice, which was undertaken here also, was compulsory in those warlike times for all males above the age of six years. If you look carefully, you can still see the marks where they sharpened their arrows on the great Roman stones at the base of the wall in the Kaleyards. Butts for the practice of archery were first provided on the Jousting Croft in 1562, with the sanction and approbation of the Mayor and Corporation and rules laid down which included penalties for "Layers of Wadgers."

But such

romantic

scenes

of the past are

extremely

difficult

to

imagine

as

we

gaze

down

at

the

dustbins

and

back

doors

of

a

brand-new

commercial

development,

occupying

what

was

formerly

known

as Mercia

Square. But such

romantic

scenes

of the past are

extremely

difficult

to

imagine

as

we

gaze

down

at

the

dustbins

and

back

doors

of

a

brand-new

commercial

development,

occupying

what

was

formerly

known

as Mercia

Square.

This

entire

area,

hard

by

the Cathedral and

Eastgate

Clock

(see

below),

and

thus

frequented

by

more

visitors

than

probably

any

other

part

of

the

walls,

was

shamefully

allowed

to

remain

derelict

for

a

remarkable

number

of

years,

the

land

changing

hands

a

number

of

times

as

the

speculator's

game

ran

its

course.

In

time,

various

development

proposals

came

to

light,

whose

merits-

or

otherwise-

were

debated

in

the

local

press.

Here

was

a

golden

opportunity,

people

said,

to

produce

something

worthy

of

the

site's

prominent

position

in

a

historic

city

centre.

But

it

was

not

to

be:

the

third-rate

prevailed

yet

again

and

the

result

lies

before

us

now.

Reader Andy Wressel wrote

to tell us about his memories of the place as it used to be:

"I remember the bar / restaurant on the upper level of Mercia Square called Duke's Wine Bar. When you entered through the glass door you found yourself in a dark room with an L-shaped bar straight in front of you. Its restaurant was to the left of the entrance and I seem to remember wagon wheels were the theme here decorating the walls.

Next to Duke's, with an adjoining internal door, was a bar called The Pump Room. I also recall this bar had a revolving door leading from the square. The decor here was old wooden barrels used as tables.

Also on Mercia Square was the wine bar Pierre Griff's, with its 'P.Gs' motif in the window with what could only be described as a drunken cherub straddling a barrel. Inside, wine bottle candleholders covered with an unbelievable amount of melted wax were the centrepiece of each table. This wine bar must have been responsible for introducing many a young Cestrian to the pleasures of wine drinking as beers and spirits were not served here.

Mercia Square was always alive with a happy atmosphere; laughter echoed as many drinkers would spill out from the bars to enjoy the summer night air. Friends would use the square as a meeting point and inadvertently spend the rest of the evening there, lost in time".

As

we

learned

when

we

passed

the Kaleyard

Gate,

over

fifty

years

ago

the Greenwood

Redevelopment

Plan advocated

demolishing

the

entire

west

side

of

Frodsham

Street

and

landscaping

the

area

before

us

to

create

that

most

unfamiliar

concept

to

Chester's

contemporary

planners-

a

new

city

park

that would perpetuate the area's ancient name-

the Hop

Pole

Paddock.

If

this

project

had

gone

ahead,

the

trees

would

now

be

mature

and

the

park

would

be

treasured

as

a

green

oasis

in

the

city

centre.

Instead

of

which,

we

have

a

collection

of

exceedingly mundane

structures

with

their

backs

turned

to

the

walls,

exhibiting

a

variety

of

refuse

bins, discarded packaging

and

shabby

advertising

banners. As

we

learned

when

we

passed

the Kaleyard

Gate,

over

fifty

years

ago

the Greenwood

Redevelopment

Plan advocated

demolishing

the

entire

west

side

of

Frodsham

Street

and

landscaping

the

area

before

us

to

create

that

most

unfamiliar

concept

to

Chester's

contemporary

planners-

a

new

city

park

that would perpetuate the area's ancient name-

the Hop

Pole

Paddock.

If

this

project

had

gone

ahead,

the

trees

would

now

be

mature

and

the

park

would

be

treasured

as

a

green

oasis

in

the

city

centre.

Instead

of

which,

we

have

a

collection

of

exceedingly mundane

structures

with

their

backs

turned

to

the

walls,

exhibiting

a

variety

of

refuse

bins, discarded packaging

and

shabby

advertising

banners.

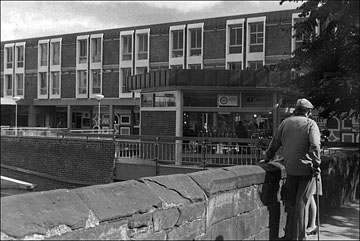

Right: the short-lived Mercia Square precinct as seen from the City Walls. More photographs of it are here.

Mind

you,

it

could

have

been

worse- just.

At the end of the nineteenth century, it was proposed that Chester's revolutionary new electricity generating station should be built here in the old Hop Pole Paddock- much to the distress of many, including the Cathedral authorities, who in October 1893 wrote to the council that it "would be a grievous eyesore and a permanent injury to the City itself if that site is so used... Architecturally, the works would seriously effect the Cathedral which is now such an attractive feature of the City... The Chapter have always been desirous of the Hop Pole Paddock being kept as open space for the benefit of the City at large and they are quite willing to approach the Ecclesiastical Commissioners in order to see whether some substantial step can be taken to place the Paddock in trust for the enjoyment of the citizens".

The Mayor assured the Dean and Chapter that their appeal would "receive the careful consideration of the Council" but, by the following January

(1894) they had formerly decided that the thing would be built here anyway, despite objections, and also that "having settled on the site, it was not for them to deal with suggestions for keeping open space" (sounds familiar?)

In March 1894, the Cathedral authorities offered to pay the sum of £1,000 to purchase the Paddock, but their offer was initially rejected, the committee declaring that this was still the best site for the generating station. A mere month later, however, came an abrupt about-turn when the council decided to accept the Cathedral's £1,000 subject to the following conditions, 1. That it never be built upon and be forever kept open and, 2. That the Chapter relinquish the Corporation a strip of land 12 feet wide at the back of Frodsham Street if and whenever the Corporation require it for widening that street".

The electricity generating station was eventually opened in 1897 in the Water Tower Gardens at the so-called Old Port instead, where, after a long resident's battle to fight off a developer's bid to demolish it, it (or at least a token part of its' facade) remains today.

And today's Cathedral authorities, intent as they apparently are to pave over the churchyard and build on the Deanery Field, would be wise to rmember the splendid efforts of their predecessors in preserving green open space in Chester "for the enjoyment of the citizens"...

In 1921, shares were offered for a proposed Scala cinema in Frodsham Street. This was intended to be built on the site of the Hop Pole Hotel (actually 13 Foregate Street) but the plan failed to come about. Then, ten

years

after

the

Greenwood

plan-

around

1959-

it

was

proposed

to

erect

an

eight-storey

steel

and

glass office

block in

the

middle

of

Mercia

Square- another philistine plot that thankfully came to nought.

Nontheless,

if

you

would

view

the

innovative,

the

inspiring,

the

sympathetic

in

contemporary

British

architecture

and

town

planning,

it

pains

me

to

say

that

this

particular

corner

of

modern

Chester

is

decidedly

not

the

place

to

be.

And

indeed,

in

early

2000,

we

were

concerned

to

hear

that

a

company

by

the

name

of Ethel

Austin

Shop

Properties had

sought- and obtained-

planning

permission

to

erect

a

two-storey

building

in

Frodsham

Street,

immediately

next

to

the

pedestrian

access

to

the

13th

century

Kaleyard

Gate,

a

location

described

by

the

city's

conservation

officer

as "an

exceptionally

sensitive

site".

This, happily, came to nought as the company soon after went into receivership but a more serious threat emerged at the end of 2010, a ludicrous plan to transfer Chester's Market Hall from the site it has traded on since Saxon times- the Market Square- and erect a new building to house it, of all places here on the Kaleyards! Go here for

the

details... And

indeed,

in

early

2000,

we

were

concerned

to

hear

that

a

company

by

the

name

of Ethel

Austin

Shop

Properties had

sought- and obtained-

planning

permission

to

erect

a

two-storey

building

in

Frodsham

Street,

immediately

next

to

the

pedestrian

access

to

the

13th

century

Kaleyard

Gate,

a

location

described

by

the

city's

conservation

officer

as "an

exceptionally

sensitive

site".

This, happily, came to nought as the company soon after went into receivership but a more serious threat emerged at the end of 2010, a ludicrous plan to transfer Chester's Market Hall from the site it has traded on since Saxon times- the Market Square- and erect a new building to house it, of all places here on the Kaleyards! Go here for

the

details...

The Eastgate

Clock

Moving

on,

the

walkway

becomes

briefly

hemmed

in

by

tall

buildings

on

either

side-

the

one

on

the

right

being

a

cafe,

if

you're

in

need

refreshments

or

a

bathroom-

and

through

the

narrow

space

between

we

spy

what

is

said

to

be

the

second-most

photographed

clock

in

Britain- the

first,

of

course,

being

so-called Big

Ben in

London-

the Eastgate

Clock.

In

fact,

it

is

unusual not to

see

visitors

from

somewhere

in

the

world

standing

beneath

this

clock

having

their

picture

taken.

Many

consider

it

curious

that

such

an

ancient

city

as

Chester

should

be

symbolised

by

a

monument

just

over

a

century

old!

At

the

end

of

the

19th

century

there

was

much

discussion

as

to

the

best

method

of

commemorating

Queen

Victoria's

Diamond

Jubilee-

60

years

on

the

throne-

and

a

committee

was

convened

to

settle

the

matter.

Altogether, Chester had raised £1,800 for the Jubilee Fund, one-third being for "general rejoicings", one-third for a nursing scheme but the final third was the sublect of much debate. Some

wanted

support

for

their

favourite

charities.

Extensions

to

the Bluecoat

School and Infirmary were

suggested.

The

inevitable

statue

was

proposed.

But then the

offer

of

a

commemorative

clock

was

made

by Colonel

E.

Evans-Lloyd ('citizen and freeman'),

and

this

was

accepted.

The

eminent

Chester

architect, John

Douglas was

asked

to

design

it,

and

some

local

relations

of

his,

the Swindleys of

Overleigh

Road,

who

happened

to

be

specialists

in

ornamental

ironwork,

were

commisioned

to

produce

the

mounting

for

the

clock

and

the

railings

for

the

top

of

the

gate.

The

clock

itself

was

made

by

the

old company

of J. B.

Joyce of

Whitchurch,

who

are

to

this

day

responsible

for

maintaining

it.

Douglas had considered the idea of erecting a clock here from at least 1881 when he had designed the adjoining Grosvenor Club. In 1884 the idea resurfaced when a masonry clock tower was suggested. It was only when Colonel Evans-Lloyd's proposals prevailed that the commission finally went ahead. Douglas had considered the idea of erecting a clock here from at least 1881 when he had designed the adjoining Grosvenor Club. In 1884 the idea resurfaced when a masonry clock tower was suggested. It was only when Colonel Evans-Lloyd's proposals prevailed that the commission finally went ahead.

The clock was run by weights instead of springs, thus enabling it to keep more accurate time. The pendulum was said to beat every one and a quarter seconds and the pendulum ball weighed one hundred-weight.

The clock's builders formerly had to make frequent visits to wind the mechanism but

since

its

conversion

to

electricity,

this

is

no

longer

necessary.

The clock was formally unveiled at a civic ceremony in 1899 by the Mayoress of Chester and Miss Sybil Clarke, Col. Evans-Lloyd's niece. During the ceremony, Colonel Evans-Lloyd said the clock was his humble contribution to his native city and he "hoped that by day and night it would prove to be a comfort and convenience, noy only to the citizens, but to the many tourists who visited the city".

For years, he said, he had wished to see a clock on the Eastgate and he had first investigated the possibility ten years previously, though the difficulty had always been to find a receptacle on which to place it. The handsome Jubilee Memorial Tower had finally solved the problem.

J. B. Joyce, the designers of the Eastgate Clock, continue in business to this day- they even have a website- and are now part of the Smith of Derby Group. Founded in 1690, they are arguably the oldest surviving clockmaking company and their clocks grace buildings throughout the world. One of the most famous is the magnificent mechanism and dial at the Shanghai Custom House. Built in 1927, it was the largest clock ever made at the time and became affectionately known as 'Big Ching'. J. B. Joyce, the designers of the Eastgate Clock, continue in business to this day- they even have a website- and are now part of the Smith of Derby Group. Founded in 1690, they are arguably the oldest surviving clockmaking company and their clocks grace buildings throughout the world. One of the most famous is the magnificent mechanism and dial at the Shanghai Custom House. Built in 1927, it was the largest clock ever made at the time and became affectionately known as 'Big Ching'.

Other Joyce clocks are in the post offices in Sydney and Adelaide in Australia; in Nairobi, Cape Town and Port Elizabeth in Africa and in Rangoon, Calcutta, Delhi and Kabul in Asia. There are also Joyce clocks in North and South America and in Canada, and there's even one on the Falkland Islands, at Port Stanley. Much nearer and more familiar to Cestrians is the distinctive Joyce clock which stands atop a pole a mere few hundred yards for the Eastgate at the end of Foregate Street. It appears in this photograph in our 'lost pubs of Chester' gallery- the two old pubs in the picture have long since vanished, replaced by soulless office buildings, but the clock survives and continues to accurately tell us the time to this day.

Since its unveiling, our Eastgate Clock has been universally admired. Even the notoriously difficult-to-please architectural critic Nikolaus Pevsner evidently approved of the design and described it and the gateway it tops

thus: "a

rusticated

elliptical

arch,

on

it

jolly

ironwork

carrying

a

diamond

Jubilee

Clock,

by

Douglas,

and

surprisingly

playful".

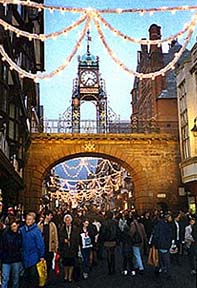

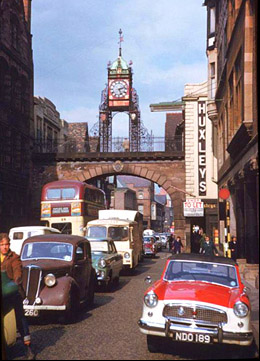

Our photograph shows heavy traffic passing beneath the Eastgate and its clock on a Summer day in 1961. The buildings look much the same today but this notorious bottleneck thankfully vanished when much of the city centre was pedestrianised.

1997

was

the

official

centenary

of

the

Eastgate

Clock,

and

the

occasion

was

marked

by

a

variety

of

events,

including

photography

and

painting

competitions

and

a

classic

car

run

between

Big

Ben

in

London

and

the Eastgate in Chester. 1997

was

the

official

centenary

of

the

Eastgate

Clock,

and

the

occasion

was

marked

by

a

variety

of

events,

including

photography

and

painting

competitions

and

a

classic

car

run

between

Big

Ben

in

London

and

the Eastgate in Chester.

Its architect, John Douglas (1830-1911)- who was also responsible for the beautiful east side of St. Werburgh Street, the rebuilt Shoemaker's Row in Northgate Street, the impressive residences in Bath Street, the City Baths and his own home, the vast Walmoor House on Dee Banks, now lies beneath a humble tombstone in the remarkable Overleigh Cemetery, across the River Dee in Handbridge.

In early 2015, a £500,000 restoration commenced upon the Eastgate. The clock's ornate ironwork is being restored, as are sections of the gate's sandstone structure and heraldry. Consequently, the entire structure has been encased in scaffolding and a protective covering has been added which contains a photographic image of the bridge and clock, showing visitors Chester’s world-famous landmark hidden behind the wrap. The clock's hands protrude through the screen and continue to show the time.

This image has, since its erection, provided a great deal of local amusement due to the clock face having been printed the wrong way round!

Ascending

the

short

flight

of

steps

to

stand

directly

under

the

clock,

we

suddenly encounter

below

us

the

unexpected

bustle

of Eastgate and Foregate

Streets,

deemed

the

principal

shopping

area

of

the

city

centre.

The

attractive

cobbled

surface

here

was

laid

as

recently

as

1998

and

is

a

great

improvement

upon

the

former

tarmac

surface.

Now

go

on

to Part

II of

our

exploration

of

Eastgate

Street...

Curiosities from Chester's History no. 10

- 1485 Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field and his body hurredly interred in the choir of a nearby monastery, that of the Greyfriars. Henry Tudor- a Welshman- ascends the throne as Henry VII (1457-1509) and starts the Tudor dynasty.

On 24th August 2012, the University of Leicester and Leicester City Council, in association with the Richard III Society, announced that they had joined forces to begin a search for the mortal remains of King Richard III. They set out to locate the remains of the church of the Grey Friars- long since demolished and now lying beneath a council car park!- and establish whether the remains of Richard III were still buried there.

On 5th September 2012 the excavators announced that they had identified the site of the Greyfriars church and human bones have since been found in the church's choir. On 12th September 2012 it was announced that a skeleton discovered during the search could be that of Richard III. Five reasons were given: the body was of an adult male; it was buried beneath the choir of the church; there was scoliosis of the spine, making one shoulder higher than the other; there was an arrowhead embedded in the spine; and there were perimortem injuries to the skull. Further laboratory tests, including DNA comparisons, are planned to verify the identification. Watch this space...

Simon Ripley becomes twenty third Abbot of St. Werburgh's (-1493)

- 1486 Henry VII further reduced the fee farm rent to £20. The citizens claimed the walls and a quarter of the city were in ruins and the city sparsely populated on account of the wealthier merchants having moved to more prosperous towns.

- 1489 Prince Arthur (1486-1502), eldest son of Henry VII stayed at Chester for a month and witnessed the Miracle Play 'The assumption of our Lady' performed at the Abbey Gate. He was described as "a great friend to the monks".

(One of the great 'what-ifs' of English history: if Arthur, "friend to the monks" had survived to become king instead of his younger brother Henry and the Dissolution of the Monasteries and creation of the Church of England had never have come about, what manner of country would we be living in now?)

Prince Arthur raised the Mayor, Richard Goodman to an Esquire. The Pentice Court was raised on the south and east sides of St. Peter's Church. The steeple was re-pointed and a goose was eaten at the top of it by the Parson and his friends, after which "they threw the bones into the four streets"

- 1493 John Puleston Esq. of Wrexham, almost killed one Patrick Kelling at the high altar of the Abbey, and so suspended the services of the church. John Birchenshawe becomes twenty fourth Abbot of St. Werburgh's (-1524)

- 1497 Katherine Knight and "the wife of John Bowes" were fined 4d for 'eaves-dropping".

- 1500 The Handbridge side of the Old Dee Bridge was rebuilt and towers added to give greater protection against the marauding Welshmen. First recorded horseraces on the Roodee. The first black-lead pencils used in England

- 1501 Arthur, eldest son of Henry VII and the first Tudor Prince of Wales, marries Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536). He died the following year, aged only sixteen years- and she went on to become the first wife of his younger brother, Henry VIII, who was six years her junior.

- 1503 All who held the rank of Mayor or Sheriff, and all innkeepers ordered to hang out lanterns , until the 8pm curfew. The order stated that all concerned "were to have hanging at their dores a lanthorne wyth a candyll byrning in it every nighte from that it be first night unto the oure of viii of the clocke, from the feast of All Saints (November 1st) until the feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary." (February 2nd) After that, apart from the watchman's fire-brazier, absolute darkness would prevail until daybreak. The streets from the High Cross to Eastgate and to St. Michael's in Bridge Street were paved for the first time. Following the death of Prince Arthur two years earlier, Prince Henry (soon to be Henry VIII) was created Earl of Chester. Nostrodamus was born in this year. He started to write his prophesies around 1550. They were translated into English in 1672 by another French doctor, Theophilus Garencieres, whose son, Dudley, came to Chester in 1676 and served as Rector of Waverton. He was buried in the Cathedral in 1702. Dudley's wife, Elizabeth, was half-sister to another famous Cestrian, the architect and dramatist Sir John Vanbrugh.

- 1505 Chester's 'Great Charter' granted by Henry VII. This allowed that Chester be separate from the County, with the exception of the Castle and Gloverstone- a sort of no-man's land between the Castle and the City- with the title "The County of the City of Chester", and the Mayor was given the right to have his sword carried with the point erect before him, except in the King's presence. It permitted the city to appoint its own magistrates and be governed by its appointed Mayor along with 24 Aldermen, 40 Councillors, 1 Recorder, 2 Sheriffs, 2 Coroners and 2 Murangers. In this year, the old steeple of St. Werburgh's Abbey was deemed unsafe and taken down.

- 1507 The sweating sickness prevalent; 91 people died in 3 days. It was said that middle aged, red-faced people were particularly prone to the disease. During the plague, nobody was permitted to leave the city and dogs had to be kept indoors. Dirt and rubbish was not allowed to be thrown into the street, as was the usual custom. Doors of affected houses were marked with the words "Lord have mercy on us."

|

fter

our

tour

of

of

the Cathedral,

we

will

now

rejoin

the

City Walls

and

wander

on. You

will

hardly

fail

to

notice

a distinctive

tall

modern structure

situated

in the corner of the churchyard here.

This

free-standing bell tower

or campanile is

known

as

the Addleshaw

Tower,

after

its

commissioner,

Dean

Addleshaw.

It

was

built

to accomodate the Cathedral's bells after

the

decaying bell frame in the

15th

century

central

tower

began

to

show

signs

of

stress

and

judged

no

longer

capable

of

supporting

their

great

weight.

fter

our

tour

of

of

the Cathedral,

we

will

now

rejoin

the

City Walls

and

wander

on. You

will

hardly

fail

to

notice

a distinctive

tall

modern structure

situated

in the corner of the churchyard here.

This

free-standing bell tower

or campanile is

known

as

the Addleshaw

Tower,

after

its

commissioner,

Dean

Addleshaw.

It

was

built

to accomodate the Cathedral's bells after

the

decaying bell frame in the

15th

century

central

tower

began

to

show

signs

of

stress

and

judged

no

longer

capable

of

supporting

their

great

weight.