p

to

the

18th

century, burials

within

Chester

Cathedral,

and the Abbey before it, were

common

and

much

sought-after.

p

to

the

18th

century, burials

within

Chester

Cathedral,

and the Abbey before it, were

common

and

much

sought-after.

A contributor to The Cheshire Sheaf in 1879 wrote: "St. Werburgh's Abbey at Chester was a favourite place of sepulture from very early days, as the numerous memorial slabs taken out from the lower levels close to the rock, during the recent restoration, very fully prove".

The

cost

towards

the

end

of

the

practice,

to

those

not

privileged

to

free

access,

was

"£5

for

burial

in

the

side

alleys

and

£10

in

the

body

of

the

quire".

At the time, this was a

considerable

sum,

but

nontheless,

the

cumulative

effect

of

hundreds

of

such

interments

eventually

resulted

in

a

serious

undermining

of

the

Cathedral's

fabric-

by

Scott's

time,

the

side

walls

of

the

eastern

end

were

noted

to be

leaning feet

out

of

true.

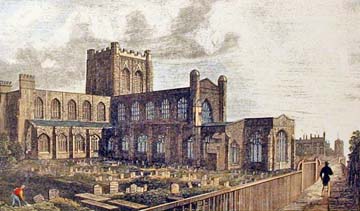

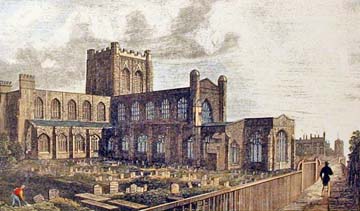

Many

of

the

external

features

you

see

today

are by its major restorer Sir George Gilbert Scott,

including

the

spires

and

small

towers

atop

the

main

tower,

which

had

been

originally

built

about

1210

and

which was

described by him,

before

its

long-overdue restoration,

as

a "picturesque

and

crumbling

pile

of

soft

sandstone,

inhabited

by

jackdaws".

A confirmation of this state of affairs comes in the form of an interesting reminiscience from the February 1882 edition of the Sheaf, wherein a contributor recalled, "When some fifty years younger than I am now, I used to watch with boyish interest the movements of the sable birds that then flourished in and about the crumbling and crannied walls of Chester Cathedral. The jackdaws' nests were up far away out of ordinary reach; but the increase in population was at times so great, and the birds made such havoc in the spongy and perishing stone, that a raid had each season to be made upon them to keep the colony down. Long ladders were projected at all sorts of angles, and a dozen or two eager marauders pursued their deadly mission at the mouths of the principal nests. I'm afraid I was myself at such times one of the foremost invaders of the poor birds' territory, and have gone home at night laden with the spoil of their young".

The

exterior

facing

of

the

13th

century

Lady

Chapel,

the

building

nearest

to

the

East Wall,

is

also

Scott's.

It

is

as

if

the

entire

structure

had

been

'wrapped

up'

in

a new

stone overcoat -

but

there

is

less

obviously

new

work

inside

the

Cathedral

but

many

of

the

monastic

buildings-

considered

to

be

the

finest

in

Britain-

survive

relatively

unchanged.

Among

them

is

the Refectory,

where

once

the

monks

ate

their

frugal

meals

in

silence,

except

for

the

voice

of

one

of

the

brothers

giving

bible

readings

from

the

late

13th

century

stone

lectern

or

pulpit,

which

is

built

into

the

wall

and

reached

by

an

arcaded

stairway.

It,

too,

is

considered

to

be

to

be

one

of

the

finest

in

the

country.

The

exterior

facing

of

the

13th

century

Lady

Chapel,

the

building

nearest

to

the

East Wall,

is

also

Scott's.

It

is

as

if

the

entire

structure

had

been

'wrapped

up'

in

a new

stone overcoat -

but

there

is

less

obviously

new

work

inside

the

Cathedral

but

many

of

the

monastic

buildings-

considered

to

be

the

finest

in

Britain-

survive

relatively

unchanged.

Among

them

is

the Refectory,

where

once

the

monks

ate

their

frugal

meals

in

silence,

except

for

the

voice

of

one

of

the

brothers

giving

bible

readings

from

the

late

13th

century

stone

lectern

or

pulpit,

which

is

built

into

the

wall

and

reached

by

an

arcaded

stairway.

It,

too,

is

considered

to

be

to

be

one

of

the

finest

in

the

country.

The

Refectory

itself,

though

basically

Norman,

was

remodelled

in

the

13th

century

and

the

windows

were

altered

again

in

the

15th

to

give

the

impression

of

a

later

building.

One

modern

addition

is

the

magnificent

medieval-style

hammer-beam

roof

which

was

built

under

the

direction

of

architectural

historian

F. H.

Crossley

as

recently

as

1939.

After

a

period,

ending

in

1876,

housing The

King's

School,

(look

for

the

grafitti

scratched

into

the

walls by generations of long-dead pupils)

the

Refectory

is

today

filled

with

the

gentle

chatter

of

visitors

and

other

refugees

from

the

busy

city

outside,

having

resumed

some

of

its

ancient

function

by

serving

as

the

Cathedral's

teashop

and

restaurant.

The

East

Window

had

been

completely

rebuilt

by

Giles

Gilbert

Scott

in

1913

and

in June

2001,

to

mark

the

new

Millennium,

a

great

new

stained

glass

west

window

was

installed

in

the

Refectory.

Created

by

Bristol-based

artist Rosalind

Grimshaw,

assisted

by Patrick

Costeloe,

the

window

was

inspired

by

the

biblical

quotation, "And

God

saw

everything

He

had

made,

and

behold

it

was

very

good".

There

are

six

main

panels,

each

two

feet

wide

and

sixteen

feet

high,

depicting

the

six

days

of

Creation,

including

the

passing

from

darkness

into

light,

the

creation

of

dry

land

from

the

water

and

the

coming

of

fish,

sea

creatures

and

Also

ranking

as

some

of

the

finest

of

their

kind

are

the

highly-decorated

oak Choir

Stalls of

c.1380 (illustrated

at the top of the page)

with

their

imaginatively-carved misericords.

Despite

having

been

moved

several

times

over

the

centuries,

they

have

nontheless

survived

intact

and

with

remarkably

little

sign

of

wear

or

damage

for

over

six

hundred

years of regular use.

Novelist Henry

James was

inspired

by "the

vast

oaken

architecture

of

the

stalls,

climbing

vainly

against

the

dizzier

reach

of

the

columns".

Also

ranking

as

some

of

the

finest

of

their

kind

are

the

highly-decorated

oak Choir

Stalls of

c.1380 (illustrated

at the top of the page)

with

their

imaginatively-carved misericords.

Despite

having

been

moved

several

times

over

the

centuries,

they

have

nontheless

survived

intact

and

with

remarkably

little

sign

of

wear

or

damage

for

over

six

hundred

years of regular use.

Novelist Henry

James was

inspired

by "the

vast

oaken

architecture

of

the

stalls,

climbing

vainly

against

the

dizzier

reach

of

the

columns".

(Read

his

affectionate

description

of

Chester

in

his "most

perfect" 1903

novel, The

Ambassadors here).

These misericords ("mercy seats") are

small

shelves

which

project

from

the

undersides

of

the

hinged

choir

stall

seats

upon

which

the

monks

supported

themselves

during

the

long

hours

of

worship. Because

they

were

usually

tucked

away

out

of

sight,

the

the

carvers

were

allowed

considerable

freedom

of

expression

in

their

decoration.

The

exquisite

finesse

of

the

pinnacled

canopies

over

the

choir

stalls

contrast

sharply

with

the

earthly

subject

matter

on

the

misericords

beneath-

men

wrestle,

foxes

steal

grapes,

a

wife

beats

her

husband,

a

unicorn

is

slain

after

laying

its

head

in

the

lap

of

a

virgin,

angels

play

lutes

and

biblical

scenes

are

flanked

by

monsters

and mythological

figures

from

distant

pre-Christian

times-

all

of

the

utmost

liveliness

and

fascination.

The

story

of St. Werburgh-

to

whom

the

Cathedral

is

dedicated-

and

the

'restored

goose'

is

here

also,

but

some

of

these

medieval

masterpieces

are

now

sadly

lost

to

us,

for

150

years

ago,

Dean

Howson

ordered

five

of

them

to

be

destroyed

on

the

grounds

that

they

were "very

improper"..

A complete photographic record of the misericords of Chester cathedral- and of many other places- may be found on Dominic Strange's excellent website, Misericords of the World.

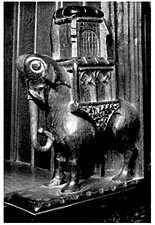

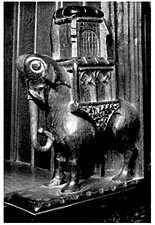

Look

out

also

for

the

curious

cloven-hoofed elephant on

the

end

of

one

of

the

choir stalls-

the

fanciful

creation

of

a

medieval

craftsman

who

had

obviously

never

laid eyes upon

the

real

thing.

One

had

been

brought

to

England

in

1255,

a

gift

to

Henry

III

from

Louis

IX

of

France,

and

carvings

made

of

it

at

the

time

were

the

model

for

copies

which

appeared

for

more

than

a

century

afterwards. Elephants

had

first

come

to

Britain

long

before

this,

however,

for

a

troop

of

them

had

accompanied

the Emperor

Claudius during

the

first

days

of

the

400-year

Roman

occupation

of

our

islands,

when

he

rode

in

state

to Camulodunum (modern

Colchester)

in

August

AD

43

to

accept

the

surrender

of

several

of

the

local

tribes-

to

whom

the

great

creatures

must

have

been

a

truly

awe-inspiring

sight.

Look

out

also

for

the

curious

cloven-hoofed elephant on

the

end

of

one

of

the

choir stalls-

the

fanciful

creation

of

a

medieval

craftsman

who

had

obviously

never

laid eyes upon

the

real

thing.

One

had

been

brought

to

England

in

1255,

a

gift

to

Henry

III

from

Louis

IX

of

France,

and

carvings

made

of

it

at

the

time

were

the

model

for

copies

which

appeared

for

more

than

a

century

afterwards. Elephants

had

first

come

to

Britain

long

before

this,

however,

for

a

troop

of

them

had

accompanied

the Emperor

Claudius during

the

first

days

of

the

400-year

Roman

occupation

of

our

islands,

when

he

rode

in

state

to Camulodunum (modern

Colchester)

in

August

AD

43

to

accept

the

surrender

of

several

of

the

local

tribes-

to

whom

the

great

creatures

must

have

been

a

truly

awe-inspiring

sight.

While

on

the

subject

of

cloven

hooves,

here

is

a

curious

story

recorded

by

one

Mr

Edward

Thomas

in

a

1906

edition

of

the Cheshire

Sheaf:

"When

I

became

a

chorister

in

Chester

Cathedral

in

the

year

1828,

I,

as

was

the

custom

with

all

new

boys,

was

shown

by

the

older

choristers

a

flagstone

at

the

north

east

corner

of

the cloisters on

which

was

a

mark (below),

said

to

be

the Devil's

footprint,

and

was

told

that

if

the

flag

was

removed

and

replaced

by

a

new

one,

on

the

following

morning,

the

footprint

would

be

there

again".

To

the

best

of

our

knowledge,

this

splendid

legend

has

of

recent

times

become

entirely

forgotten-

it

certainly

appears

in

no

contemporary

guidebooks

we

have

seen.

Our

photograph

shows

the

nearest

thing

we

could

find

to

a

'Devil's

Footprint'-

perhaps

now somewhat

worn

since

it

was

exhibited

for

the

edification

of

those Georgian

choir

boys.

To

the

best

of

our

knowledge,

this

splendid

legend

has

of

recent

times

become

entirely

forgotten-

it

certainly

appears

in

no

contemporary

guidebooks

we

have

seen.

Our

photograph

shows

the

nearest

thing

we

could

find

to

a

'Devil's

Footprint'-

perhaps

now somewhat

worn

since

it

was

exhibited

for

the

edification

of

those Georgian

choir

boys.

The

Devil

makes

yet

another

appearance

in

a

better-known

Cathedral

legend,

that

of

the Chester

Imp.

This

tells

us

that,

centuries

ago,

during

the

construction

of

the

nave,

a

priest

was

startled

by

the

sight

of

a

demonic

face

leering

at

him

through

one

of

the

windows.

This

he

took

to

be

Satan

himself,

come

to

investigate

this

latest

fortress

against

his

dark

powers.

Prompt

action

was

taken,

and

stonemasons

were

ordered

to

carve

an

equally-ugly

image

and

mount

it

where,

should

the

Devil

dare

to

look

in

again,

he

would

be

frightened

away!

At

intervals,

from

the mid-18th century

onwards,

attempts

were

made

to

hold

music

festivals

in

the

Cathedral.

Conscious

of

the

fact

that

the

rapidly-rising

and

wealthy

cities

of

Liverpool

and

Manchester

were

easily

able

to

attract

the

best

artistes,

Chester's

organisers

strove

to

compete,

but

were

continually

running

into

difficulties.

In

1821,

for

example,

one Madame

Camporese caused

a

great

stir

due

to

the

high

level

of

fees

she

demanded

for

performing.

The still-thriving Chester

Chronicle dryly

commented

at

the

time: "We

are

sorry

that

anything

like

dissatisfaction

should

have

been

expressed

by

the

lady,

after

the

very

liberal

treatment

she

experienced

from

the

committee.

We

believe

she

only

gave

five

songs

in

the

church,

for

which

she

had

£150,

enough

in

all

common

conscience

one

would

have

thought.

The

air

of

Italy,

however,

as

connected

with

pecuniary

matters,

has

unquestionably

a

bracing

tendency".

In

1842,

the

festival

had

to

be

cancelled

as "the

Bishop

has

objected

to

sanction

it

on

account

of

the

concerts

and

ball

which

follow

the

oratorio,

and

the

Dean

and

Chapter

have

refused

to

lend

the

nave

of

the

Cathedral

for

the

morning

performances".

The

citizens

of

Chester

were

said

to

have

been

"highly

incenced" by

the

uncooperative

attitude

of

the

Cathedral

authorities.

Today, however, Chester

Cathedral

continues

to

host

a

wide

variety

of (considerably

better

organised)

musical

events. Just last week, this writer and his wife greatly enjoyed a performance of one of his favourites, Mahler's Symphony no 2, 'The Resurrection', performed by the Chester Philharmonic Orchestra.

The Treasure House Mystery

The Treasure House Mystery

Sir George Gilbert Scott, restorer of the Cathedral, believed in the existence of a secret chamber concealed somewhere within its walls, and for two centuries or upwards lost sight of by the authorities.

Perhaps this was because he had heard that the whole of the Cathedral's records, except some Treasurers' and Receivers' papers, and a few detached fragments, were all missing for at least a century after its foundation. And it certainly is strange that little or nothing prior to the Restoration should remain in the hands of the Chapter authorities- no Chapter Act Books, no church plate, no ancient manuscripts, no library, no counterpart leases, not even the precious Charter of the Cathedral itself! What became of it all? Destruction at the time of the Civil War is one alternative, the other a secret storehouse, perhaps walled up, during the Siege, and never revealed to the successors of those responsible appointed at the Restoration.

Right: Norman and Gothic architecture side by side in the North Transept of the Cathedral

Sir Peter Leycester, in his Antiquities Touching Cheshire, referring to the Charters granted by Earl Hugh to St. Werburgh's Abbey in 1093, says "This agrees in time with the Original Charter of the Foundation, which I transcribed out about 1644, then remaining among the Evidences of that Church, which were then kept in a certain room within St. Werburgh's Church in Chester." He says further, that the Evidences in question were "after removed thence in the late War". Sir Peter was resident in Chester throughout the Siege.

16th century Treasurers' Accounts of the Dean & Chapter confirm the existence then and for nearly a century afterwards of the Cathedral Treasure House:

• 1572-3. For tacking of (taking off) a locke in ya tresery house, and me'dyng ye same xiijd.

• 1583. For 2 lodes of coles and two of turfes for the Treasure house xvijd.

• 1584. Payd to Stocken (the smith) for openinge of the lockes of the Treasure house dore iijd.

• 1602. For a new key to the Treasure house dore vjd.

• 1604. For mending the looke of the Treasure house dore iiijd.

• 1623. A locke and key for the letters Patients iiijd.

From this date, the Treasure House is no more named in the Chapter records. But if it be the same room with which Sir Peter Leycester was acquainted, the disappearance of the chamber is contemporaneous with the last days of the Siege of Chester in 1646.

Unlike the terrible damage inflicted upon Chester in the Civil War, three centuries later, during World War II, it largely escaped the appalling mayhem visited upon many British cities, incuding neighbouring Liverpool. The Chester Chronicle of September 9th 1939 carried the following remarkable announcement:

"No special steps are being taken to protect the fabric or the contents of the Cathedral from attack. It is pointed out that adequate protection of the fabric would be too costly an undertaking. Unlike some cathedrals, Chester has not got a rich store of treasures".

During late 1940 and the early months of 1941, the city experienced its worst attacks from enemy bombers. The Cathedral suffered damage during the raids of November 29th / 30th and on December 1st 1940 when incendiary bombs blew out many windows, including those of the St. Erasmus Chapel, the Choir Clerestory and the South Nave Aisle. There was also much damage done to the roofs. The cost of repairs was recorded as amounting to "six thousand, five hundred and thirty eight pounds, six shillings and eleven pence."

In 1949, the Cheshire Sheaf recorded that the following anonymous poem was found "on the back of an old picture in Chester Cathedral"...

In 1949, the Cheshire Sheaf recorded that the following anonymous poem was found "on the back of an old picture in Chester Cathedral"...

Isn't it strange that princes and kings,

And clowns that caper in sawdust rings,

And ordinary folk like you and me,

Are builders for eternity?

To each is given a bag of tools,

An hourglass and a book of rules,

And each must build, ere his life is flown,

A stumbling-block or a stepping stone.

A locally better known poem is that which is inscribed upon an old clock in the Cathedral:

When as a child I laughed and wept- time crept.

When as a youth I dremed and telked- time walked.

When I became a full grown man- time ran.

And later as I older grew- time flew.

Soon I shall find

while travelling on- time gone.

Will Christ have saved my soul by then?- Amen.

The

first

known

guidebook

to

Chester,

the De

Laude

Cestrie ('In

Praise

of

Chester')

was

written

about

1195

by Lucian,

one

of

the

monks

of

the

Abbey.

For

some

fascinating

insights

into

the

city

and

Abbey

as

he

saw

them

at

the

end

of

the

12th

century,

go here.

From the 12th century to the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1540s, fully 25% of the area within Chester's walls was occupied by monastic communities. To

learn

a

little

of

the

Benedictine

nuns

of

St. Mary's,

go here. You

can also find out something more of them, together with the Black Friars, in our Roodee chapter and of the Grey and White Friars in our Watergate chapter. Alternatively,

visit

a

stunningly

beautiful

building,

still

very

much

with

us- well over

a thousand

years

old

and

our

city's first cathedral:

the

unique

church

of St. John

the

Baptist.

On we go to discuss some of the controversies concerning Chester Cathedral in modern times....

On we go to discuss some of the controversies concerning Chester Cathedral in modern times....

p

to

the

18th

century, burials

within

Chester

Cathedral,

and the Abbey before it, were

common

and

much

sought-after.

p

to

the

18th

century, burials

within

Chester

Cathedral,

and the Abbey before it, were

common

and

much

sought-after.

Also

ranking

as

some

of

the

finest

of

their

kind

are

the

highly-decorated

oak Choir

Stalls of

c.1380 (illustrated

at the top of the page)

with

their

imaginatively-carved misericords.

Despite

having

been

moved

several

times

over

the

centuries,

they

have

nontheless

survived

intact

and

with

remarkably

little

sign

of

wear

or

damage

for

over

six

hundred

years of regular use.

Novelist

Also

ranking

as

some

of

the

finest

of

their

kind

are

the

highly-decorated

oak Choir

Stalls of

c.1380 (illustrated

at the top of the page)

with

their

imaginatively-carved misericords.

Despite

having

been

moved

several

times

over

the

centuries,

they

have

nontheless

survived

intact

and

with

remarkably

little

sign

of

wear

or

damage

for

over

six

hundred

years of regular use.

Novelist  Look

out

also

for

the

curious

cloven-hoofed elephant on

the

end

of

one

of

the

choir stalls-

the

fanciful

creation

of

a

medieval

craftsman

who

had

obviously

never

laid eyes upon

the

real

thing.

One

had

been

brought

to

England

in

1255,

a

gift

to

Henry

III

from

Louis

IX

of

France,

and

carvings

made

of

it

at

the

time

were

the

model

for

copies

which

appeared

for

more

than

a

century

afterwards. Elephants

had

first

come

to

Britain

long

before

this,

however,

for

a

troop

of

them

had

accompanied

the

Look

out

also

for

the

curious

cloven-hoofed elephant on

the

end

of

one

of

the

choir stalls-

the

fanciful

creation

of

a

medieval

craftsman

who

had

obviously

never

laid eyes upon

the

real

thing.

One

had

been

brought

to

England

in

1255,

a

gift

to

Henry

III

from

Louis

IX

of

France,

and

carvings

made

of

it

at

the

time

were

the

model

for

copies

which

appeared

for

more

than

a

century

afterwards. Elephants

had

first

come

to

Britain

long

before

this,

however,

for

a

troop

of

them

had

accompanied

the  To

the

best

of

our

knowledge,

this

splendid

legend

has

of

recent

times

become

entirely

forgotten-

it

certainly

appears

in

no

contemporary

guidebooks

we

have

seen.

Our

photograph

shows

the

nearest

thing

we

could

find

to

a

'Devil's

Footprint'-

perhaps

now somewhat

worn

since

it

was

exhibited

for

the

edification

of

those Georgian

choir

boys.

To

the

best

of

our

knowledge,

this

splendid

legend

has

of

recent

times

become

entirely

forgotten-

it

certainly

appears

in

no

contemporary

guidebooks

we

have

seen.

Our

photograph

shows

the

nearest

thing

we

could

find

to

a

'Devil's

Footprint'-

perhaps

now somewhat

worn

since

it

was

exhibited

for

the

edification

of

those Georgian

choir

boys. The Treasure House Mystery

The Treasure House Mystery In 1949, the Cheshire Sheaf recorded that the following anonymous poem was found "on the back of an old picture in Chester Cathedral"...

In 1949, the Cheshire Sheaf recorded that the following anonymous poem was found "on the back of an old picture in Chester Cathedral"...