ollowing

the

rule

of St. Benedict, the

monks

of

Chester

Abbey

lived lives of simplicity, held all things in common, worshipped

eight

times

a

day,

studied,

cared

for

the

sick,

welcomed

travellers

and

distrubed alms to

the

poor. ollowing

the

rule

of St. Benedict, the

monks

of

Chester

Abbey

lived lives of simplicity, held all things in common, worshipped

eight

times

a

day,

studied,

cared

for

the

sick,

welcomed

travellers

and

distrubed alms to

the

poor.

Around the year 1195, one of their number, Lucian, wrote enthusiastically of his brothers:

"The visitor meets with a cheery

and kindly welcome and with joyful and affectionate looks. Food is put before

him and a place at table is freely granted him with befitting graciousness.

In their (the monks) characters are found simplicity, sincerity and refinement;

in their manners orderliness, calm and self-control. Their goodness, as if emanating

from the atmosphere of the place, should refresh every human mind.

Just as we

praise well-trained men because they are not borne down by the weight of their

arms or the pertinacity of the enemy, so we admire the monks of Chester because

they are not wearied by the toil of their joyful yoke.

To the local people they

are are cheery; to those who come from afar they are jovial, ready to open their

hearts to them. The seats about their table are worn by reason of their being

well-known and frequented by strangers.

Seldom are they free from crowds flocking

round them, and in all this do they follow the example of their King - if much

has been given you, distribute it liberally; if little, this also impart cheerfully."

Bear in mind the importance with which the activities of these

monks were held by the entire society. They were considered of equal status to, for example, the military: the role of the soldier was to defend the country, perhaps giving his life in the process, while the monk devoted his life to prayer- it was believed by all to be vitally necessary to keep the 'spiritual batteries' topped up in order to defend the world from the clutches of the Evil One. Bear in mind the importance with which the activities of these

monks were held by the entire society. They were considered of equal status to, for example, the military: the role of the soldier was to defend the country, perhaps giving his life in the process, while the monk devoted his life to prayer- it was believed by all to be vitally necessary to keep the 'spiritual batteries' topped up in order to defend the world from the clutches of the Evil One.

During

the

later

middle

ages,

however,

the

Abbey

became

extremely

rich

and

powerful,

owning

land

and

property

throughout

Cheshire

and

far

beyond.

The Earls

of

Chester gave

the

Abbots

rights

equal

within

their

jurisdiction

to

their

own,

which

were

themselves

equal

to

those

of

the

Crown

elsewhere

in

the

country.

They

were

strict

landlords

and

hard

taskmasters.

The

medieval

trials

by

fire,

water

and

combat

were

practiced

in

the

Abbot's

courts

and

malefactors

were

summarily executed

by

the

Abbot's

officers.

After

the

Dissolution,

ecclesiastical

justice

continued

to

be

administered

in

the

Lady

Chapel.

It

was

here,

in

1555,

that George

Marsh,

a

widower

with

children,

was

condemned

to

death

for

preaching

the

'heretical'

doctrine

of Martin

Luther by the Bishop of Chester, George Coats.

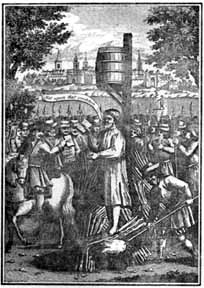

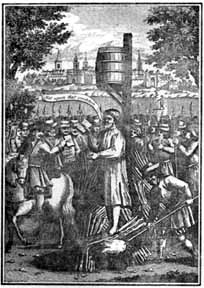

George Marsh was the only person martyred in Cheshire under Queen Mary. He was a preacher from Deane, a suburb of Bolton. He first went about the neighbouring villages preaching stories from the bible but was later employed by King Edward VI in 1547 as a preaching minister. He was a tall man and an eloquent speaker. But during the reign of Queen Mary his preaching came into conflict with the new Catholic ways. He was brought before Justice Barton at Smithills Hall near Bolton (A sign there draws the visitor's attention to a mark in the floor, said to be a footprint made by Marsh when he stamped his foot during his interrogation). He refused to deny his beliefs and so was imprisoned for a time at Lancaster Castle where people flocked to his prison cell to hear him preach.

He was then moved to Chester to be tried and imprisoned in the terrible Northgate Gaol. He was given the chance to go free if he recanted but his refusal sealed his fate. He dragged on a hurdle to Spital Boughton (Chester's traditional place of execution, overlooking the River Dee about a mile from the town) where he was tied to the stake and a barrel of tar was set above his head to drip on him as he burned. It is said that the fire was badly managed and his death was "protracted". After it was over, his ashes were collected by his friends and buried in St Giles' Cemetery nearby. The spot where he, and countless others, died so cruelly is today marked by a memorial obelisk erected in the 19th century. He was then moved to Chester to be tried and imprisoned in the terrible Northgate Gaol. He was given the chance to go free if he recanted but his refusal sealed his fate. He dragged on a hurdle to Spital Boughton (Chester's traditional place of execution, overlooking the River Dee about a mile from the town) where he was tied to the stake and a barrel of tar was set above his head to drip on him as he burned. It is said that the fire was badly managed and his death was "protracted". After it was over, his ashes were collected by his friends and buried in St Giles' Cemetery nearby. The spot where he, and countless others, died so cruelly is today marked by a memorial obelisk erected in the 19th century.

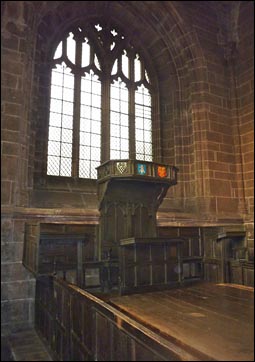

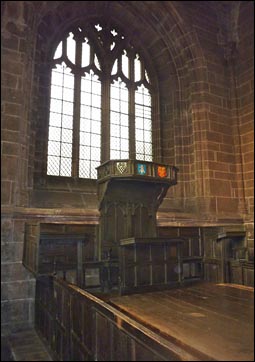

In

1636,

the

Bishop's,

or Consistory, Court

(illustrated right) was

moved

from the Lady Chapel into

the

unfinished

south-west

tower

of

the

Cathedral,

where

its

heavy oak

furnishings- an enclosure with a bench, surrounding a large table,

may still be inspected by visitors

today,

the

only

complete

example

to survive in

all

of

England. Consistory courts dealt with all manner of legal issues affecting the church, some of a life and death seriousness but many more trivial- disputes about alterations to church buildings and the like. The last case heard at Chester was in the 1930s and concerned a priest who had attempted suicide.

Although the spiritual activities of the Abbey continued, by

the

14th

century,

many

of

the

monks

were

living

a

life

of

relative

ease,

often

discarding

their

habits

for

fashionable

dress

with

ornamental

belts

and

trimmings.

They

hunted

in

the

forest

and

feasted

noisily-

their

scraps

going

not

to

the

poor

but

to

feed

greyhounds

and

hunting

dogs.

Around

1480,

it

was

recorded

that "divers

wymen"

were

accused

of

being

"the

paramours

of

the

monkes

of

Chester".

The

Abbot

was

all-powerful

within

his

domain,

answerable

only

to

the

Bishop

and

the

Pope.

By

the

16th

century,

the

monks

were

building

fine

new

halls

on

their

estates,

the

chief

of

these

being

at Saighton Grange,

about

four

miles

south-east

of

Chester,

where

they

laid

out

a

thousand-acre

park. The

Abbot

was

all-powerful

within

his

domain,

answerable

only

to

the

Bishop

and

the

Pope.

By

the

16th

century,

the

monks

were

building

fine

new

halls

on

their

estates,

the

chief

of

these

being

at Saighton Grange,

about

four

miles

south-east

of

Chester,

where

they

laid

out

a

thousand-acre

park.

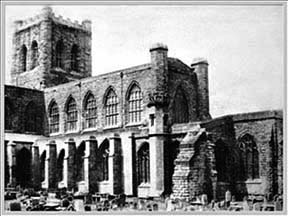

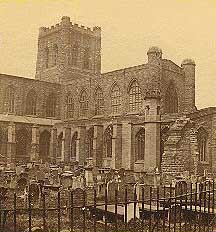

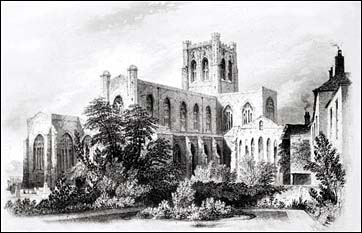

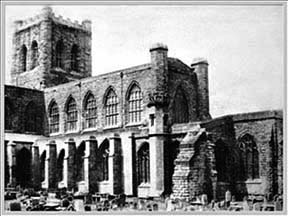

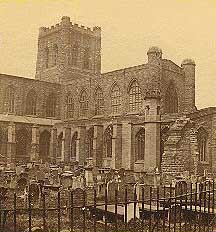

A 19th century photograph of the Cathedral, taken just before the commencement of its radical restoration. No trace of the wall on the right or of the extensive graveyard remain with us today.

The Domesday Book

records

Saighton

as

belonging

to

'St. Werburgh's',

referring

to

the

Saxon

minster

run

by

canons-

the

Benedictine monks

came

six

years

later,

in

1092.

They

developed

the

land

as

a

grange,

or

agricultural

estate,

later

incorporating

a

country

retreat

for

the Abbots.

In

1249

they

'crennelated'- fortified-

the

buildings, the

Welsh

border

being

not

far

away,

and

in

the

1490s,

during

the

reign

of

Henry

VII,

Abbot

Simon

Ripley

rebuilt

the

gatehouse

and

marked

it

with

his

crest

of

a

black

dog

and

the

motto "Advance

Boldly".

The only surviving part of the monastic grange is the gatehouse, which has been designated by English Heritage as a Grade I listed building, and is one of only two surviving monastic manorial buildings in Cheshire, the other being Ince Manor. The

rest

of

the

buildings

are

Victorian

and

modern

and

are

now

the

home

of Abbey

Gate

College,

whose

motto

remains "Advance

Boldly".

But all

this

was

to

end

suddenly in

1540

with

the

Reformation

and

Henry

VIII's Dissolution

of

the

Monasteries.

In

the colourful

words of local guide and author Thomas

Hughes, "Bluff

King

Hal,

that

shameless

polygamist,

in

a

fit

of

pretended

religious

zeal,

dissolved

all

these

fraternities,

and,

pocketing

the

spoil,

dealt

out

their

lands

to

his

creatures

with

right

royal

munificence".

Throughout

the

country,

the

splendid

old buildings

were

dismantled

and

sold

off

for

building

materials

and

the

monks

cast

out,

but

in

Chester,

St. Werburgh's

Abbey

was

transformed

into

the 'Cathedral

Church of Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary' and

thus

it

was

that John

Clarke,

the

25th

and

last

Abbot,

became

the

first

Dean.

He

did

not

long

enjoy

his

new

office,

which

began

4th

August

1541,

as

he

died

the

following

month.

We

can hardly

blame

Abbot Clarke

for

surrendering

his

monastery,

for

it

had

become

obvious

that

there

was

no

alternative-

his

predecessor,

Thomas

Marshall,

who

had

been

become

Abbot

of Colchester

Abbey,

refused

to

give

up

his

house,

and, in 1539,

was

hanged

outside

its

gates.

The

same

thing

happened

to

the

Abbots

of Reading and Glastonbury.

Of

the

twenty two

monks

resident

at

the

Abbey

in

1538,

ten

were

selected

to

remain

as

members

of

the

Cathedral

staff

and

the

rest

were

issued

with

pensions

and

lump-sum

gratuities

of

approximately

a

half-year's

pension,

in

order

to

pay

for

their

secular

clothing,

food

and

accomodation

until

their

first

pension

payments

became

due.

Thus,

they

can

hardly

be

said

to

have

been

harshly

treated.

"A Mouldering Sandstone Cliff"

At

first,

the

fabric

of

the

new cathedral

was

treated

with

almost

as

little

respect

as

that

of

the

other

dissolved

abbeys.

By

1580,

it

was said to be "in

great

decay

and

the

glasse

thereof

carryed

to

their

pryvate

benefices

by

the

Dean

and

Chapter".

When

the

Roman Legions

built

the

fortress

of

Deva,

they

were

obliged

to

utilise

the

local

sandstone,

but

had

the

wisdom

to

use

only

the

hardest

types

available.

(Chester's

finest

extant

example

of

Roman

masonry,

the North

Wall,

in

places

stands

strong

and

proud

after

seventeen

centuries).

The

monks

of

the

rapidly-expanding

Abbey

seemingly

lacked

the

Roman

engineer's

knowledge

and

worked

largely

with

softer,

but

more

easily

obtainable,

types

of

stone.

Consequently,

over

the

centuries,

the

fabric

of

the

building

became

seriously

eroded.

The

Cathedral,

in

common

with

the

rest

of

the

town,

had

been

badly

treated

during

the

Siege

of

Chester

during the English Civil War in

the

1640s,

and

lead

was

stripped

from

the

roof

in

order

to

make

musket

balls. When

the

Roman Legions

built

the

fortress

of

Deva,

they

were

obliged

to

utilise

the

local

sandstone,

but

had

the

wisdom

to

use

only

the

hardest

types

available.

(Chester's

finest

extant

example

of

Roman

masonry,

the North

Wall,

in

places

stands

strong

and

proud

after

seventeen

centuries).

The

monks

of

the

rapidly-expanding

Abbey

seemingly

lacked

the

Roman

engineer's

knowledge

and

worked

largely

with

softer,

but

more

easily

obtainable,

types

of

stone.

Consequently,

over

the

centuries,

the

fabric

of

the

building

became

seriously

eroded.

The

Cathedral,

in

common

with

the

rest

of

the

town,

had

been

badly

treated

during

the

Siege

of

Chester

during the English Civil War in

the

1640s,

and

lead

was

stripped

from

the

roof

in

order

to

make

musket

balls.

In the early years of the 18th century, the famous author

of Robinson Crusoe, Moll Flanders and much else, Daniel

Defoe wrote of his visit to the Cathedral, "'tis

built

of

a

red,

sandy,

ill-looking

stone,

which

takes

much

from

the

beauty

of

it,

and

which

yielding

to

the

weather,

seems

to

crumble,

and

suffer

by

time,

which

much

defaces

the

building"

and

by

1798,

it

was

described

as "one

of

the

most

heavy,

irregular

and

ragged

piles".

Years later, the author Charles Hiatt recalled that "the surface rot of the very perishable red sandstone, of which the cathedral was built, was positively unsightly" and that the "whole place, before its restoration, struck one as woebegone and neglected; it perpetually seemed to hover on the verge of collapse, and yet was without a trace of the romance of the average ruin".

Not that

the

problems

of

decaying

stonework

and shoddy maintainance were confined

just to

the

Cathedral.

The

lovely

church

of St. John

the

Baptist over

the

centuries

suffered

no

less

than three collapses

of

its towers-

the

central

tower twice during

the

middle

ages

and

the

great

west

tower

as

recently

as

1881.

Writing

of

the

West

Front

of

the

Cathedral

in

1854, author and guide Thomas

Hughes said "Time

has,

of

course,

been

at

work

here,

as

elsewhere,

gnawing

away

at

the

old

red

sandstone;

but

there

is

still

enough

left

to

give

us

an

idea

of

its

ancient

beauty...

but it is

now

fast

going

to

decay." Writing

of

the

West

Front

of

the

Cathedral

in

1854, author and guide Thomas

Hughes said "Time

has,

of

course,

been

at

work

here,

as

elsewhere,

gnawing

away

at

the

old

red

sandstone;

but

there

is

still

enough

left

to

give

us

an

idea

of

its

ancient

beauty...

but it is

now

fast

going

to

decay."

(This remarkable aerial view- a detail from John McGahey's famous View of Chester from a Balloon- shows the cathedral and its surroundings as they appeared around this time).

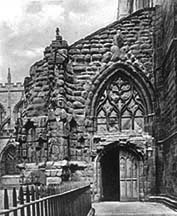

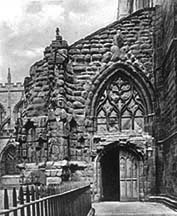

Right: "The decay has gone deep into the stone and left its courses projecting, rounded and shapeless, like the layers of a mouldering rock"

Consequently,

a

number

of

more-or-less

necessary

restorations

have

taken

place. An early one- in 1702- was financed by King William III allowing the Dean & Chapter to organise a general collection throughout the parish churches of the entire country; fourteen shillings and sixpence was donated by the congregation of Llanymblodwell and four shillings and sixpence from Llanymynech, both in Montgomeryshire and the good folk of Ormesby St. Margaret in Norfolk contributed two shillings and twopence. As many as four restorations took place during

the

19th

century

alone-

by Thomas

Harrison in

1818-20, R. C. Hussey in

1843, Sir

George

Gilbert

Scott in

1868-76

and Sir

Arthur

Blomfield in

1882-87.

Thomas Harrison, the prolific Chester architect who was also responsible for the Grosvenor Bridge, the rebuilding of the Castle, the Northgate and much else, fell out seriously with the Dean and Chapter who, while

responsible for the maintainance of the Cathedral fabric, wanted to pay someone else less than he asked to supervise the plans he had so painstakingly prepared. In a forthright letter, he "presumed the Dean... wished to have a man of some experience to advise with, and superintend, the necessary works of this decayed building" and then asked rhetorically, "You cannot imagine that I, or any other person, would willingly lend his name as architect to the repairs required in this almost ruinous church... without having the superindendence of such repairs. Would the public be as ready to free me from the responsibility of any failure as the Chapter express themselves to be? I doubt it much".

Harrison was famously abrupt, but he knew his business and his opinion was doubtless valid, since, amazingly, virtually no maintainance work had been carried out on the building since the 1530s- 300 years previously!

What the aforementioned Dean and his preceding 'guardians of the fabric' had been doing during all this time is anyone's guess. Nontheless, the work on rebuilding the buttresses of the south transept, whose stability had long been a cause for concern, and also of repairing its gutters, went ahead without him. The latter work was so badly executed that it had to be redone a mere six years later. To add insult to injury, Harrison was not even paid his princely fee of £25 for his work during his lifetime. He may have considered himself a professional man, worthy of reasonably prompt payment for services rendered, but in the eyes of that 'Man of God', the Dean of Chester, he was a mere tradesman, whose bills could be paid when it was deemed convenient- or not at all. The money only appeared ten years after Harrison's death, and then only then when his executors threatened to kick up a fuss about it.

Scott's

restoration was

by far the

most

radical-

before work commenced, he

wrote

that

virtually

the

entire

building "was

so

horribly

and

lamentably

decayed

as

to

reduce

it

to

a

mere

wreck,

like

a

mouldering sandstone

cliff". In a lecture in 1870 outlining his proposals, he declared that "probably no building in England has suffered so severely... the decay has gone deep into the stone and  left its courses projecting, rounded and shapeless, like the layers of a mouldering rock. It is a distressing kind of work, yet, if conscientiously carried out it is the saving of the old design, even though the old material gives way to new." left its courses projecting, rounded and shapeless, like the layers of a mouldering rock. It is a distressing kind of work, yet, if conscientiously carried out it is the saving of the old design, even though the old material gives way to new."

The

situation

is clearly

illustrated

in

the

two

photographs

above-

both

of

which

had

been

taken

after

some

restoration

had

taken

place-

notice

how

radically

different

those

sections

appear.

Chester Cathedral bathed in winter sunlight: January 2007, photographed by the author.

Scott

was

amazed

to

discover

that

the

eastern

part

of

the

church

had no

foundations

at

all,

and

it

consequently

had

to

be

underpinned,

with

foundations

inserted

and

missing

buttresses

replaced. Work

on

the

Lady

Chapel

revealed,

at

a

depth

of

nine

feet

below

the

present

surface,

a

Roman

concrete

floor,

a

drain

and

traces

of

a

road,

which

ran

diagonally

under

the

south-eastern

buttress.

His aim in the restoration was to make the building conform to his Victorian concept of a mid-thirteenth century 'ideal' but he seems to have overdone it to a great degree, especially on the outside of the building- the numerous 'fancy' features such as the flying buttresses, the parapets along the lines of the roof, the many pinnacles, the gargoyles and the curious five-sided apse at the end of the South Choir Aisle are all his inventions, being entirely absent in the original. It was also his intention to erect a tall steeple on top of the central tower but lack of money meant that this was never achieved. The four over-large turrets atop the tower would doubtlessly have looked more in keeping had this been built.

When the work was complete, one writer thought the Cathedral "a building which, if rather painfully new in appearance, is at least sound, strong and water-tight".

Another of the strange medieval carvings in the choir of Chester Cathedral- half beast, half pilgrim enjoying a mug of ale.

Sir George

(1811–78) was a leader in the Gothic Revival in England and may be better known the architect of some of London's best known landmarks, the Albert Memorial, St. Pancras Station (where his son, also named George, tragically committed suicide in 1897) and the Foreign & Commonwealth Office in Whitehall. His working life had commenced with less glamourous commissions, however, notably workhouses and prisons. During his long carreer, he found time to build or restore over 700 buildings around the country. Apart from Chester, Sir George also restored Ely Cathedral and Westminster Abbey- where he is buried.

Sir George's

grandson, Sir

Giles

Gilbert

Scott (1880–1960) also

undertook

an

extensive

programme

of

restoration

at

Chester

in

1911-13,

including

the

refectory

and

the

badly-decayed cloisters-

at

the

same

time

as

he

was

also

engaged

in

an

epic

undertaking

twenty

miles

away:

the

construction

of

the

swan

song

of

the

Gothic

in

England,

the

stupendious Liverpool

Anglican Cathedral. He now lies at the crossing beneath his gigantic tower.

Sir

Giles

was

also

the

architect of Battersea Power Station, restored the House of Commons Chamber after it was damaged in a bombing raid in 1941 and designed the famous British K2 red telephone box- compare its proportions with those of the great tower of Liverpool Cathedral- the similarities are unmistakable!

When

you

come

to

the

UK,

a

visit

to

Chester's

ancient

cathedral

followed

by

the

two

magnificent

modern

ones

in

Liverpool

is

an

unforgettable

experience. This writer would be pleased to be your guide...

Now

go

on

to part

III of

our

exploration

of

Chester

Cathedral...

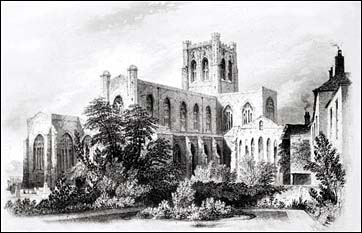

Chester Cathedral in 1811

Curiosities from Chester's

History no. 9

1399 Henry

Bolingbroke,

Duke

of

Lancaster

(later King Henry IV: 1367-1413) mustered

his

troops

under

the

walls

and

marched

against Richard

II,

whom

he

took

at Flint

Castle.

He

returned

to

Chester

with

the

unfortunate

monarch

(dressed

in

the

monk's

robe

in

which

he

attempted

to

escape)

and

the

Earl

of

Salisbury,

"mounted

on

two

little

white

nagges

not

worth

40

francs"

and

lodged

them

in

the Castle.

After

resting

in

a

tower

over

the

outer

gateway,

they

were

escorted

to

Westminster.

Piers

Legh,

a

supporter

of

Richard,

would

not

accompany

them,

as

he

was

executed

and

his

head

was

displayed

on

one

of

the

Castle's

towers.

Bolingbroke

deposed

Richard-

who

was

murdered

in

prison

the

following

year-

and

was

elected King

Henry

IV by

Parliament. 1399 Henry

Bolingbroke,

Duke

of

Lancaster

(later King Henry IV: 1367-1413) mustered

his

troops

under

the

walls

and

marched

against Richard

II,

whom

he

took

at Flint

Castle.

He

returned

to

Chester

with

the

unfortunate

monarch

(dressed

in

the

monk's

robe

in

which

he

attempted

to

escape)

and

the

Earl

of

Salisbury,

"mounted

on

two

little

white

nagges

not

worth

40

francs"

and

lodged

them

in

the Castle.

After

resting

in

a

tower

over

the

outer

gateway,

they

were

escorted

to

Westminster.

Piers

Legh,

a

supporter

of

Richard,

would

not

accompany

them,

as

he

was

executed

and

his

head

was

displayed

on

one

of

the

Castle's

towers.

Bolingbroke

deposed

Richard-

who

was

murdered

in

prison

the

following

year-

and

was

elected King

Henry

IV by

Parliament.

These

great

events

were,

of

course,

immortalised

by

Shakespeare

and John

Speed commented

of

Richard,

"If

to

spare

his

people's

bloud

he

was

contented

so

tamely

to

quit

his

royall

right,

this

fact

doth

not

only

seeme

excusable,

but

glorious;

but

men

rather

think

that

it

was

sloth,

and

a

vaine

trust

in

ddissimulation

which

his

enemies

had

long

since

discovered

in

him."

- 1400 The

Blue

Bell

Inn in

Lorimer's

Row, Northgate

Street dates

from

this

period.

The

Mayor

ordered

to

"apprehend

and

imprison

John

and

Adam

Hesketh

for

they

had

broken

into

the

Castle

and

stolen

the

keys

to

the Eastgate,

beheaded

Thomas

Molineux

and

proclaimed

against

the

King."

- 1403

The

citizens

of

Chester

were

pardoned-

upon

payment

of

300

marks-

for

encouraging

the

rebellion

of

the

Earl

of

Northumberland

and

his

son Lord

Percy (known

as

Hotspur)

against

King

Henry

IV.

They

had

proclaimed

on

two

occasions

that

Richard

II

was

alive,

and

imprisoned

in Chester

Castle. Henry, Prince of Wales, issues an order expelling the Welsh from Chester.

- 1413

Henry

IV

died,

his

son

ascended

as Henry

V (1386-1422).

Thomas

Erdeley

becomes

twentieth

Abbot

of

St.

Werburgh's

(-1434)

- 1422

Henry

V

died.

His

9

month-old

son

ascended

the

throne

as Henry

VI (1421-1471).

- 1431 Joan

of

Arc burned

at

the

stake

at

Rouen

- 1435

A

great

dearth

in

Chester:

the

people

made

bread

of

peas, feathers and

fern

roots.

This

strange

reference

to

eating

feathers

probably

occured

due

to

a

scribe's

misunderstanding

regarding vetches-

wild

peas-

as

vetches

was

also

the

name

given

to

the

flights

of

arrows

made

from

feathers!

John

de

Saughall

becomes

twenty

first

Abbot

of

St.

Werburgh's

(-1455)

- 1438

Inca

rule

established

in

Peru

- 1441

Rockley

and

Rooley,

gaolers

of

the

Castle

and Northgate,

fought

a

pitched

battle

to

settle

their

differences

on

the Roodee

- 1445

Henry

VI

visited

Chester

at

a

time

when

the

river

was

silted

up,

and

no

large

ship

could

approach

within

12

miles

of

the

city,

and

the

town

was

consequently

in

a

desolute

and

ruinous

condition

with

a

declining

population.

The

King

agreed

to

remit

half

of

the

£100

per

annum

fee

farm

rent

charged

under

the

charter

of

Edward

I.

|

ollowing

the

rule

of St. Benedict, the

monks

of

Chester

Abbey

lived lives of simplicity, held all things in common, worshipped

eight

times

a

day,

studied,

cared

for

the

sick,

welcomed

travellers

and

distrubed alms to

the

poor.

ollowing

the

rule

of St. Benedict, the

monks

of

Chester

Abbey

lived lives of simplicity, held all things in common, worshipped

eight

times

a

day,

studied,

cared

for

the

sick,

welcomed

travellers

and

distrubed alms to

the

poor.  Bear in mind the importance with which the activities of these

monks were held by the entire society. They were considered of equal status to, for example, the military: the role of the soldier was to defend the country, perhaps giving his life in the process, while the monk devoted his life to prayer- it was believed by all to be vitally necessary to keep the 'spiritual batteries' topped up in order to defend the world from the clutches of the Evil One.

Bear in mind the importance with which the activities of these

monks were held by the entire society. They were considered of equal status to, for example, the military: the role of the soldier was to defend the country, perhaps giving his life in the process, while the monk devoted his life to prayer- it was believed by all to be vitally necessary to keep the 'spiritual batteries' topped up in order to defend the world from the clutches of the Evil One. He was then moved to Chester to be tried and imprisoned in the terrible Northgate Gaol. He was given the chance to go free if he recanted but his refusal sealed his fate. He dragged on a hurdle to Spital Boughton (Chester's traditional place of execution, overlooking the River Dee about a mile from the town) where he was tied to the stake and a barrel of tar was set above his head to drip on him as he burned. It is said that the fire was badly managed and his death was "protracted". After it was over, his ashes were collected by his friends and buried in St Giles' Cemetery nearby. The spot where he, and countless others, died so cruelly is today marked by a memorial obelisk erected in the 19th century.

He was then moved to Chester to be tried and imprisoned in the terrible Northgate Gaol. He was given the chance to go free if he recanted but his refusal sealed his fate. He dragged on a hurdle to Spital Boughton (Chester's traditional place of execution, overlooking the River Dee about a mile from the town) where he was tied to the stake and a barrel of tar was set above his head to drip on him as he burned. It is said that the fire was badly managed and his death was "protracted". After it was over, his ashes were collected by his friends and buried in St Giles' Cemetery nearby. The spot where he, and countless others, died so cruelly is today marked by a memorial obelisk erected in the 19th century.

The

Abbot

was

all-powerful

within

his

domain,

answerable

only

to

the

Bishop

and

the

Pope.

By

the

16th

century,

the

monks

were

building

fine

new

halls

on

their

estates,

the

chief

of

these

being

at Saighton Grange,

about

four

miles

south-east

of

Chester,

where

they

laid

out

a

thousand-acre

park.

The

Abbot

was

all-powerful

within

his

domain,

answerable

only

to

the

Bishop

and

the

Pope.

By

the

16th

century,

the

monks

were

building

fine

new

halls

on

their

estates,

the

chief

of

these

being

at Saighton Grange,

about

four

miles

south-east

of

Chester,

where

they

laid

out

a

thousand-acre

park.

left its courses projecting, rounded and shapeless, like the layers of a mouldering rock. It is a distressing kind of work, yet, if conscientiously carried out it is the saving of the old design, even though the old material gives way to new."

left its courses projecting, rounded and shapeless, like the layers of a mouldering rock. It is a distressing kind of work, yet, if conscientiously carried out it is the saving of the old design, even though the old material gives way to new."