"We come now to notice another peculiarity of the city, which are its Rows or Galleries. As a stranger to the place, some of the descriptions I have seen in print would give me no distinct comprehension of these rows, nor am I sanguine in the hope that my own delineation will be more successful with regard to others so circumstanced.

"We come now to notice another peculiarity of the city, which are its Rows or Galleries. As a stranger to the place, some of the descriptions I have seen in print would give me no distinct comprehension of these rows, nor am I sanguine in the hope that my own delineation will be more successful with regard to others so circumstanced.

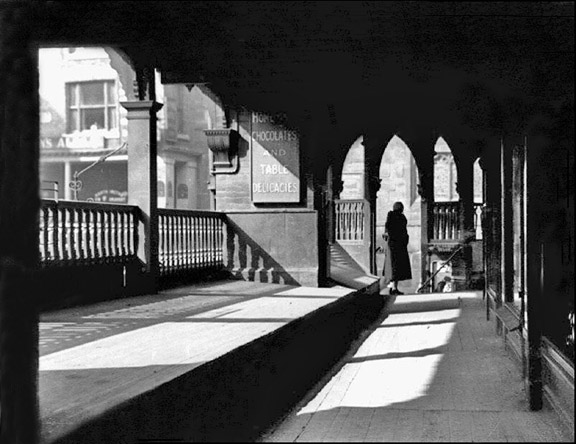

Watergate Row North by Louise Rayner (1832-1924). More of her work is here.

The rows occupy, or run parallel with a considerable portion of the four principal streets, within the walls nearest the Cross, but in no instance do they reach to any of the city gates. The level of the walking path in the rows may be reckoned generally at about twelve feet above that of the streets, though in some places not so much. It should also be observed, that besides the flights of steps by which they are entered and quitted at each end, there are other similar conveniences placed at suitable distances on the side-path which lead to and from the streets.

On passing the main street, parallel with which these rows run, a stranger would scarcely be aware of the existence of the latter. He will perceive on each side of the street, a line of shops as in other towns, and take them to be the only ones in the same front. On looking upwards, however, he will perceive a wooden or iron balustrade running along the top of these shops, with upright pillars standing at intervals of five or six yards, supporting the superincumbent buildings, which range in a direct line downwards with the shops in the street. Now the space thus created, by cutting off the communication between the summit of the lower shops, and the higher part of the building above, and which may be taken to be from ten to twelve feet, forms the front or opening of the row; backward, within this front, stands another line of shops, the interval in width, occupied as a walking path, or for other purposes, being from four to five yards. Thus the 'passengers' in the rows walk over the shops in the street, and under the first floor of the dwelling-houses; and thus two lines of shops are created in one front.

The rows are generally well flagged, and kept in good repair, and are much frequented both by the citizens and strangers, to whom they will ever prove an object of curiosity. In hot weather, a continued stream of cold air passes along the rows, from the numerons entries or avenues which branch from them; and in wet weather they afford ample protection from the "pitiless storm." Very considerable improvements in these have occurred within the last thirty years, and are daily taking place; for whenever ruin or decay render a re-erection necessary, the spirit of the times, if not the potent influence of the police, imposes a more modern and elegant form of construction. Formerly, in front of the row, was fixed a clumsy wooden railing with immense pillars of oak, supporting transverse beams, upon which the houses, chiefly built of wood and mortar rested, and which leaned forward over the street in a terrific attitude. These old erections, to the no small mortification of the admirers of antiquity, are fast decreasing in most parts of the city; though several of them yet remain, particularly in Watergate-street.

The rows are generally well flagged, and kept in good repair, and are much frequented both by the citizens and strangers, to whom they will ever prove an object of curiosity. In hot weather, a continued stream of cold air passes along the rows, from the numerons entries or avenues which branch from them; and in wet weather they afford ample protection from the "pitiless storm." Very considerable improvements in these have occurred within the last thirty years, and are daily taking place; for whenever ruin or decay render a re-erection necessary, the spirit of the times, if not the potent influence of the police, imposes a more modern and elegant form of construction. Formerly, in front of the row, was fixed a clumsy wooden railing with immense pillars of oak, supporting transverse beams, upon which the houses, chiefly built of wood and mortar rested, and which leaned forward over the street in a terrific attitude. These old erections, to the no small mortification of the admirers of antiquity, are fast decreasing in most parts of the city; though several of them yet remain, particularly in Watergate-street.

To trace the original cause of these rows, with any degree of certainty, is no easy task, concerning which a variety of conjectures have been formed. Some have attributed their origin to the period when Chester was liable to the frequent assaults of the Welsh, which induced the inhabitants to build their houses in this form, so that when the enemy should at any time have forced an entrance, they might avoid the danger of the horsemen, and annoy their assailants as they passed through the streets. This opinion seems to be adopted by Webb, and followed by most other writers on the subject. He says, "And because their conflicts with enemies continued long time, it was needful for them to leave a space before the doors of those their upper buildings, upon which they might stand in safety from the violence of their enemies' horses, and withall defend their houses from spoyl, and stand with advantage to encounter their enemies, when they made incursions".

I am aware that this has long been, and still is the popular sentiment; but I think there is very good reason to question its correctness. There is irrefragible evidence, that the form of our city is Roman, and that our walls were the work of that people; and the same reasons which justify these conclusions, are not less cogent for presuming that the construction of our streets are Roman also.

I am aware that this has long been, and still is the popular sentiment; but I think there is very good reason to question its correctness. There is irrefragible evidence, that the form of our city is Roman, and that our walls were the work of that people; and the same reasons which justify these conclusions, are not less cogent for presuming that the construction of our streets are Roman also.

Pennant appears to have been governed by this view he says, "These rows appear to me to have been the same with the ancient vestibules; and to have been a form of building preserved from the time that the city was possessed by the Romans. They were built before the doors, mid-way between the streets and the houses; and were the places where the dependents waited for the coming out of their patrons, under which they might walk away the tedious minutes of expectation. The shops beneath the rows were the cryptae and apothecae, magazines for the various necessaries of the owners of the houses."

The learned Stukeley countenances this hypothesis in his Itinerary of 1724, in which, noticing Chester, he remarks, "The rows, or piazzas, are singular through the whole town, giving shelter to the foot people. I fancied it a remain of the Roman porticoes." The authors of the Magna  Britannica dissent from the two last respectable authorities, but their objections would have been more satisfactory, if they had adduced some reasons, or suggested a more probable theory. "Mr. Pennant thinks," ( say the authors), "that he discerns in these rows, the form of the ancient vestibules attached to the houses of the Romans, who once possessed this city; many vestiges of their edifices have certainly been discovered at Chester; but there seems to be little resemblance between the Chester rows and the vestibules of the Romans, whose houses were constructed only of one story."

Britannica dissent from the two last respectable authorities, but their objections would have been more satisfactory, if they had adduced some reasons, or suggested a more probable theory. "Mr. Pennant thinks," ( say the authors), "that he discerns in these rows, the form of the ancient vestibules attached to the houses of the Romans, who once possessed this city; many vestiges of their edifices have certainly been discovered at Chester; but there seems to be little resemblance between the Chester rows and the vestibules of the Romans, whose houses were constructed only of one story."

Eastgate Row North by George Cuitt (1779-1854)

In the oldest histories extant, descriptive of this city, in some form or other, the elevated rows and the shops beneath are recognized; nor have we the slightest intimation of any period in which these rows were constructed, or when the level of the streets were sunk so much below their surface, and the ground behind them. Among the uncertain conjectures that have been hazarded on this subject, there can be no presumption in giving an opinion that their construction is of Roman origin, a position which may be maintained on several grounds of probability.

It hardly requires a word by way of argument to shew that the pavement in Bridge-street, Watergate-street and Eastgate-street, were originally on a level with the ground-floor of the houses standing in the rows; for it is utterly impossible to conceive, that the present sunken state of the streets, as contrasted with the elevated ground on each side, could be the effect of natural causes. It is most obvious, therefore, at some period or other, the principal streets have been made to take their present form by dint of human art or labour, and it is not less evident, that from the east, west, and south-gates, to the cross, and from the latter to nearly where the Exchange stands, which is almost the highest part of the city, excavation has been employed. These conclusions, which, although incapable of proof from any existing testimony, have received the concurrence of all our historians and antiquaries.

It should be remembered, too, that the city was the residence of the Romans for the space of nearly four centuries; and that the twentieth legion, with its auxiliaries was probably not less than ten thousand men. The long period therefore they were stationed here, and the multitude of their disposable hands, added to the known policy of the Romans, to keep their soldiers in active employ, afforded the best opportunity of securing all the advantages of which their knowledge of the arts and manual labour were capable of producing.

It should be remembered, too, that the city was the residence of the Romans for the space of nearly four centuries; and that the twentieth legion, with its auxiliaries was probably not less than ten thousand men. The long period therefore they were stationed here, and the multitude of their disposable hands, added to the known policy of the Romans, to keep their soldiers in active employ, afforded the best opportunity of securing all the advantages of which their knowledge of the arts and manual labour were capable of producing.

Bridge Street Row East. Unknown artist.

Thus we have the express attestation of Richard of Cirencester, that Chester was constructed by the soldiers of the twentieth. It is probable that protection and defence would be the first objects of the colonists, and it is, therefore, natural to infer that the erection of the walls would occupy their earliest efforts.

Commodiousness and convenience would next occupy their attention; and what would be more likely to present itself to the discernment of the Romans, than the desirableness of an easy access to their great court of judicature, their camp, to the auguroli and to their Praetorium, all of which were situated in the centre, or highest part of the city. The original level of the carriage road, at the junction of Watergate and Bridge-streets, may be seen by the present height of the rows in those places, and the difficulty of the ascent up those two streets for heavy carriages, may be pretty easily conceived. It is also worthy of remark, in considering this question, that these were the only parts of the city which had an immediate communication with the waters of the Dee. The river encompassed the lower parts of both, and either at one or the other it was of course necessary to land their warlike stores, forage and provisions, or other heavy materials from the vessels coming thither, requisite for the use of the garrison, from whence they had to be conveyed to the camp.

In these circumstances it appears to me, ample reasons are shewn for the necessity of reducing the steep ascent; and although they do not apply in an equal extent to Eastgate-street and Northgate-street, yet here the rise was also considerable, and the refinement of Roman taste would doubtless induce a decision for beauty and uniformity. If there be any correctness in these speculations, it does not appear that gaining new habitations, or the formation of shops on the new level, formed any part of the original Roman plan, but it is probable, that as the city increased in population and prosperity, they were formed from the sides of the wall standing between the rows and the street.

That this construction was executed by the Romans while they held possession of the city, may also be argued from its arduousness and extent. The excavations must have been made in all the streets through the solid rock, as is clearly ascertained from the back parts of the shops and warehouses, in different parts, particularly in Bridge-street and Watergate-street. The legionaries, from their numbers, leisure, and skill as artificers, seem alone capable of their execution; nor can we fix upon any other period of our history in which it is likely this immense undertaking could be performed. It is well known, that from the time of the evacuation of the island by the Romans, till within a short time of the Norman conquest, denominated the Saxon times, the city was occupied sometimes by one victor and sometimes by another, and it is hardly to he believed, that the inhabitants, but a short remove from barbarism, had either the taste or means of accomplishing so great an effort of labour or genius.

That this construction was executed by the Romans while they held possession of the city, may also be argued from its arduousness and extent. The excavations must have been made in all the streets through the solid rock, as is clearly ascertained from the back parts of the shops and warehouses, in different parts, particularly in Bridge-street and Watergate-street. The legionaries, from their numbers, leisure, and skill as artificers, seem alone capable of their execution; nor can we fix upon any other period of our history in which it is likely this immense undertaking could be performed. It is well known, that from the time of the evacuation of the island by the Romans, till within a short time of the Norman conquest, denominated the Saxon times, the city was occupied sometimes by one victor and sometimes by another, and it is hardly to he believed, that the inhabitants, but a short remove from barbarism, had either the taste or means of accomplishing so great an effort of labour or genius.

Old Shoemaker's Row, Northgate Street as portrayed by William Callow in 1854, before it was rebuilt by John Douglas. The ancient Legs of Man Inn is in the centre and the Sun Vaults is on the left. See how the Row looks now at the bottom of the page.

There are still greater improbabilities, if we refer the formation of the rows, by cutting through the ascents to a period subsequent to the conquest. Our old histories abound with various accounts of the state and condition of the public works in the city from that epoch. We have relation, as well as-existing documents, to shew by what means the bridge, the causeway, the mills, and other ancient works, were either built or kept in repair, and in what way the funds necessary for these purposes were raised. The institution of our fairs, the erection of several of our public edifices, and the origin of many ancient customs and usages, are given with great minuteness. But with regard to the excavations, inferior in labour and expence only to the erection of the walls, no mention whatever is to be found-_a circumstance which cannot be satisfactorily accounted for, or thesupposition of this great work being performed by our Norman ancestors. To this may be added, that the reason assigned for the rows, namely, the facility of resisting the incursions of the Welsh, has no weight at all in it. For against this opinion it may be urged, that in none of their attacks upon the city, did they ever force their way within the gates; so that these being proved by experience to be sufficient bulwarks against the marauders, there existed no necessity for the creation of any other defences.

The shops in the rows are generally considered the best situations for retail shop-keepers, but those on the south-side of Eastgate-street, and the east-side of Bridge-street have a decided preference. Shops let here at very high rents, and are in never-failing request; and perhaps there are no parts of the city which have undergone equally rapid or extensive improvements. A person who traversed these rows thirty years ago, would hardly recognize them by their present appearance. There was one feature in the shops, which is worthy of notice.At that period, or a little before, there was hardly a shop in the row which could boast a glass window. The fronts were all open to the row in two or three compartinents, according to their size, and at nights were closed by huge hanging shutters, fixed on hinges, and fastened in the day-time by hooks to the ceiling of the row. The external appearance of the shops, except as far as regarded the commodity for sale, was little different to that of butchers' standings. At present the shops, and many of the dwelling-houses in the rows, are equal in elegance to those of Manchester or Liverpool. In a word, Eastgate and Bridge-street, are capable of supplying all the real demands of convenience, and the artificial calls of luxury, mental and corporeal; presenting a cluster of drapers, clothiers, jewellers, perfumers, booksellers &c, as respectable as the kingdom can produce".

The shops in the rows are generally considered the best situations for retail shop-keepers, but those on the south-side of Eastgate-street, and the east-side of Bridge-street have a decided preference. Shops let here at very high rents, and are in never-failing request; and perhaps there are no parts of the city which have undergone equally rapid or extensive improvements. A person who traversed these rows thirty years ago, would hardly recognize them by their present appearance. There was one feature in the shops, which is worthy of notice.At that period, or a little before, there was hardly a shop in the row which could boast a glass window. The fronts were all open to the row in two or three compartinents, according to their size, and at nights were closed by huge hanging shutters, fixed on hinges, and fastened in the day-time by hooks to the ceiling of the row. The external appearance of the shops, except as far as regarded the commodity for sale, was little different to that of butchers' standings. At present the shops, and many of the dwelling-houses in the rows, are equal in elegance to those of Manchester or Liverpool. In a word, Eastgate and Bridge-street, are capable of supplying all the real demands of convenience, and the artificial calls of luxury, mental and corporeal; presenting a cluster of drapers, clothiers, jewellers, perfumers, booksellers &c, as respectable as the kingdom can produce".

It may come as a surprise to the reader that the above article was written over 175 years ago by local historian Joseph Hemingway and formed part of his excellent guide, the Panorama of the City of Chester (1836). To contemporary Cestrians his lengthy description of the ancient Rows seems entirely familiar.

Theories concerning the origins of the rows still abound but many years of archaeological exploration has provided the contemporary student with a few more facts than were possessed by the able Hemingway.

Five centuries after Britain ceased to be a part of the Roman Empire in AD 410, the ruins of the fortress of Deva were still impressive. Four centuries later still, however, little was left above ground- by then, much had either collapsed or been deliberately demolished in order to obtain the ready-cut blocks of stone to re-use in new buildings.

The vanished Roman Chester nontheless influenced the development of its successor, for example in the location of the main thoroughfares. Thus Bridge Street directly overlies the Via Praetoria of the fortress while Eastgate Street and Upper Watergate Street perpetuate the line of the Via Principalis. Similarly Upper Northgate Street sits over the Via Decumana and the fact that its southern continuation does not meet Eastgate Street directly opposite Bridge Street reflects the arrangement of major Roman buildings that once stood at the centre of the fortress.

The ruins of Deva were also responsible, at least in part, for the Rows. The ground behind Row properties is the same level as the first floor walkway and is thus generally 9ft (3.3m) higher than at the street frontage. This has come about because of the differential clearance of the ruins of Roman buildings which were removed along the frontages of the main streets because such areas were the most sought after as building plots in the medieval town where the majority of the inhabitants made their living through commerce.

The ruins of Deva were also responsible, at least in part, for the Rows. The ground behind Row properties is the same level as the first floor walkway and is thus generally 9ft (3.3m) higher than at the street frontage. This has come about because of the differential clearance of the ruins of Roman buildings which were removed along the frontages of the main streets because such areas were the most sought after as building plots in the medieval town where the majority of the inhabitants made their living through commerce.

To the rear, however, the debris resultant from the collapse of Roman structures, which could be up to 5ft (1.5m) thick, was left untouched and was in fact supplemented over the centuries by rubbish and building materials discarded by the residents of the street frontage properties. In certain areas, this process was accentuated by the fact that the Roman buildings were themselves higher than the streets beside them, partly because the sloping ground required them to be terraced and partly because their internal floor levels tended to rise as a consequence of successive rebuildings.

This is demonstrated by comparing floor levels in Roman buildings on opposite sides of Bridge Street. Thus, in the baths on the east side Roman floor level was approximately Ift (30cm) lower than the present pavement whereas in the building on the west side the surface of its internal courtyard was more than 3ft (90cm) higher than the modern pavement. The accumulation of deposits behind the Row properties had a benign effect upon the remains of Roman buildings as, despite robbing-out of walls for reusable stone, much was sealed and protected. This continued to be true even when these 'backland' areas came to be built over for the first time in the nineteenth century as the foundations of the Victorian buildings were generally restricted in width and depth.

This is demonstrated by comparing floor levels in Roman buildings on opposite sides of Bridge Street. Thus, in the baths on the east side Roman floor level was approximately Ift (30cm) lower than the present pavement whereas in the building on the west side the surface of its internal courtyard was more than 3ft (90cm) higher than the modern pavement. The accumulation of deposits behind the Row properties had a benign effect upon the remains of Roman buildings as, despite robbing-out of walls for reusable stone, much was sealed and protected. This continued to be true even when these 'backland' areas came to be built over for the first time in the nineteenth century as the foundations of the Victorian buildings were generally restricted in width and depth.

Over the centuries, Chester's Rows changed as individual buildings were replaced and construction methods improved: timber, wattle and thatch giving way to brick, slate and fine masonry. In addition, their extent diminished- there are many records of sections of Row being enclosed in order to 'improve' old buildings- or being omitted entirely from newer ones. An easily-inspected example of the former is the splendid Falcon Inn (above) at the juction of Bridge Street and Grosvenor Street. There has been a building here since around 1200 but the earliest documentary reference is a deed of 1602 when it was acquired as a town house from Sir George Hope by the Grosvenor family of Eaton. 40 years later at the beginning of the English Civil War the house was extensively altered by Sir Richard Grosvenor who was largely responsible for The Falcon's present appearance. Sir Richard was a leading Loyalist commander based at Chester Castle and wanted to move his family to the safety of the city, but found that the house was too small. In 1643 he petitioned the Mayor for permission to enlarge the property by enclosing the Row which he claimed "was causing an annoyance". Permission was granted and the Row was blocked off and turned into an additional room.

This enclosed Row still survives in the Front Bar where visitors can see the 13th Century stone piers which once belonged to the building's facade. The timber partition which runs through the bar is a remnant of a late medieval shop front which existed in the Row. Sir Richard's petition set a precedent which was followed by all other residents of Lower Bridge Street and by the mid 18th Century nearly all had enclosed their Rows and, in this part of the city at least, these ancient walkways were lost forever.

This enclosed Row still survives in the Front Bar where visitors can see the 13th Century stone piers which once belonged to the building's facade. The timber partition which runs through the bar is a remnant of a late medieval shop front which existed in the Row. Sir Richard's petition set a precedent which was followed by all other residents of Lower Bridge Street and by the mid 18th Century nearly all had enclosed their Rows and, in this part of the city at least, these ancient walkways were lost forever.

In Northgate Street, the southern end (extreme left of our photograph) of the ancient Shoemaker's Row was replaced in 1808 by Thomas Harrison's City Club or Commercial News Rooms. An inn had existed on this spot as far back as 1272 when Richard de Knaresburgh left his daughter a shop "near the inn which was Hugh Selimon's towards the church of St. Peter's". Nothing more is heard of it for 500 years until, in 1782, The Three Crowns' landlord was Thomas Lewis. In 1855, author and guide Thomas Hughes described the inn as having an old and picturesque gable front and that its chief entrance was from Shoemaker's Row. He also remarked that it had enjoyed its finest days long before it was eventually demolished in 1808, when its sign and licence were transferred to new premises in Pepper Alley. The rest of the Row was replaced between 1897 and 1909 by the extremely ornate development of black-and-white timber buildings we see here, different parts being designed by three architects; John Douglas, his pupil James Strong- who, a couple of years later, went on to design the ornate fire station (1911) further up Northgate Street- and the County architect Henry Beswick, who had been a pupil of Lockwood. It continued to be called a Row but now contained a single, ground-level enclosed walkway. In the basement of one of the shops here may be inspected some massive column bases from the Praetorium (headquarters building) of the Roman fortress that once stood on this spot. Many visitors express surprise that this part of the Row is largely a product of the 20th century.

Despite these losses, Chester today still boasts considerable stretches of these unique structures. Strictly protected, they will hopefully continue to delight for centuries to come and a wander along them should be considered an essential part of your visit to our beautiful city.

Want to know more? Our chapters devoted to Chester's Visitors Through the Ages contain numerous fascinating quotes about the Rows. Virtual Chester has some detailed information and you can virtually 'walk the Rows' at the wonderfully-eccentric Chester Tourist website!