G. H. Steele visited

Chester

in

the

course

of

a

short

tour of

Lancashire,

Cheshire

and

North

Wales.

Little

is

known

of

him,

except

that

he

was

born

in

Prenton

on the Wirral about

1791,

and

was

apparently

living

in

London

when

he

wrote

his

account

of

the

tour.

This

extract

is

dated

Tuesday,

18th

August

1818... G. H. Steele visited

Chester

in

the

course

of

a

short

tour of

Lancashire,

Cheshire

and

North

Wales.

Little

is

known

of

him,

except

that

he

was

born

in

Prenton

on the Wirral about

1791,

and

was

apparently

living

in

London

when

he

wrote

his

account

of

the

tour.

This

extract

is

dated

Tuesday,

18th

August

1818...

"We

then

reach

the

antient

city

of

Chester...

We

first

enter

this

city

by

Upper

Northgate

Street,

in

the

centre

of

which

we

pass

under

an

antient

gate

termed Northgate -having

three

others,

viz.,

Southgate, Eastgate and

Westgate.

In

Eastgate

street

is

a

handsome

inn

called The

Royal

Hotel,

kept

by

G.

[Thomas]

Jackson...

We

stopt

at The

White

Lion in

Northgate

Street,

kept

by

W.

Tomlinson.

Close

to

the

door

of

this

inn

is

a

mile

stone,

182

miles

from

London.

Arrive

in

Chester

about

half

past

11

o'c.

a.m.

Close

to

the

White

Lion

is

Dickson's

Bank.

Went

to

view

the

antient Cathedral.

The

interior

of

it

strikes

a

stranger

more

with

veneration

and

reverence

for

the

antiquity

of

its

sacred

walls

than

with

astonishment

and

admiration

which

can

only

be

excited

over

some

peculiar

grace

or

elegance

displayed

in

the

architecture. This

Cathedral

has

little

to

boast

of

in

that

respect

being

remarkable

for

its

plainness...

In

Northgate

Street

is

the

Town

hall

and

the

Market

place,

both

of

which

are

close

to

the

White

Lion,

from

which

inn

I

left

about

half

past

12

o'c.

noon

per

Shrewsbury

coach

for

Wrexham,

having

remained

I

hour

and

a

half

at

Chester;

the

name

of

the

coach

is Highflyer.

Just

beyond

the

city

on

the

road

to

Wrexham

we

passed

over

a

stone

bridge

built

ovor

the

Dee.

From

it

observed

the

Prison,

a

large

stone

building"

.

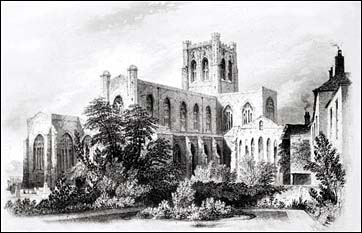

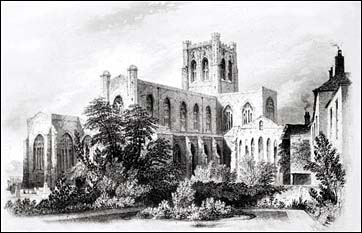

John Marsh (1752–1828) was an English music composer, born in Dorking, England. He was was perhaps the most prolific English composer of his time and is known to have written at least 350 compositions, including at least 39 symphonies. Of these, only the nine that Marsh had printed are extant, together with three one-movement finales. Marsh was a man of varied interests, and his 37 volumes of journals are among the most valuable sources of information on life and music in 18th-century England. John Marsh (1752–1828) was an English music composer, born in Dorking, England. He was was perhaps the most prolific English composer of his time and is known to have written at least 350 compositions, including at least 39 symphonies. Of these, only the nine that Marsh had printed are extant, together with three one-movement finales. Marsh was a man of varied interests, and his 37 volumes of journals are among the most valuable sources of information on life and music in 18th-century England.

In September 1819 he visited Chester as part of a journey he took around Britain. Here are his comments on the poor state of the cathedral at that time:

"On Thursday Sept’r 2d. therefore I left Manchester for the last time & went thro’ Delamere forest to Chester which I reached about noon & found I had a third time fallen in with the assizes. I however got a small bed room at the inn where I messed with a lawyer & his witnesses.

As to the Cathedral, my first object in a city, I found it hardly better worth seeing than that of Carlisle, for tho’ the nave was not wanting & it had therefore a much better appearance withinside yet without it looked like an old dilapidated, weather-beaten castle… It was however now undergoing some repairs & being therefore not in a state for divine service, I had no opportunity of hearing its choir".

(Thanks to Brian Robins- www.earlymusicworld.com- for the above).

Thomas

De

Quincey, the

'English

Opium

Eater',

frequently

came

to

Chester

to

'dry

out'

and

in

order

to

evade

creditors

and

officers

of

the

law.

His

mother

lived

in

a

house

known

as

'The Priory',

situated

among

the

now-vanished

ancient

buildings

adjoining St.

John's

Church. De

Quincey

wrote

the following about

his

wanderings

near

the

river

Dee

in

his

great Confessions of

1821: Thomas

De

Quincey, the

'English

Opium

Eater',

frequently

came

to

Chester

to

'dry

out'

and

in

order

to

evade

creditors

and

officers

of

the

law.

His

mother

lived

in

a

house

known

as

'The Priory',

situated

among

the

now-vanished

ancient

buildings

adjoining St.

John's

Church. De

Quincey

wrote

the following about

his

wanderings

near

the

river

Dee

in

his

great Confessions of

1821:

"The

streets

could

be

evaded

by

shaping

a

course

along

the

city

walls;

which

I

did,

and

descended

into

some

obscure

lane

that

brought

me

gradually

to

the

banks

of

the

river

Dee.

In

the

infancy

of

its

course

amongst

the

Denbighshire

mountains,

this

river,

famous

in

our

pre-Norman

history

for

the

earliest

parade

of

English

monarchy

(it

was

a

very

scenical

parade,

for

somewhere

along

this

reach

of

the

Dee,

Edgar,

the

first

sovereign

of

all

England,

was

rowed

by

nine

vassals reguli) -is

wild

and

picturesque,

and

even

below

my

mother's

Priory

it

wears

a

character

of

interest.

But,

a

mile

or

so

nearer

to

its

mouth,

when

leaving

Chester

for

Parkgate,

it

becomes

miserably

tame;

and

the

several

reaches

of

the

river

take

the

appearance

of

formal

canals.

On

the

right

bank

of

the

river

runs

an

artificial

mound,

called The

Cop. It

was,

I

believe,

originally

a

Danish

work;

and

certainly

its

name

is

Danish

(i.e.

Icelandic

or

Old

Danish)

and

the

same

from

which

is

derived

our

architectural

word coping.

Upon

this

bank

I

was

walking

and

throwing

my

gaze

along

the

formal

vista

presented

by

the

river.

Some

trifle

of

anxiety

might

mingle

with

this

gaze

at

the

first,

lest

perhaps Philistines might

be

abroad...

but

I

have

generally

found

that,

if

you

are

in

quest

of

some

certain

escape

from

Philistines

of

whatsoever

class-

sheriff-officers,

bores,

no

matter

what-

the

surest

refuge

is

to

be

found

amongst

hedgerows

and

fields,

amongst

cows

and

sheep..." "The

streets

could

be

evaded

by

shaping

a

course

along

the

city

walls;

which

I

did,

and

descended

into

some

obscure

lane

that

brought

me

gradually

to

the

banks

of

the

river

Dee.

In

the

infancy

of

its

course

amongst

the

Denbighshire

mountains,

this

river,

famous

in

our

pre-Norman

history

for

the

earliest

parade

of

English

monarchy

(it

was

a

very

scenical

parade,

for

somewhere

along

this

reach

of

the

Dee,

Edgar,

the

first

sovereign

of

all

England,

was

rowed

by

nine

vassals reguli) -is

wild

and

picturesque,

and

even

below

my

mother's

Priory

it

wears

a

character

of

interest.

But,

a

mile

or

so

nearer

to

its

mouth,

when

leaving

Chester

for

Parkgate,

it

becomes

miserably

tame;

and

the

several

reaches

of

the

river

take

the

appearance

of

formal

canals.

On

the

right

bank

of

the

river

runs

an

artificial

mound,

called The

Cop. It

was,

I

believe,

originally

a

Danish

work;

and

certainly

its

name

is

Danish

(i.e.

Icelandic

or

Old

Danish)

and

the

same

from

which

is

derived

our

architectural

word coping.

Upon

this

bank

I

was

walking

and

throwing

my

gaze

along

the

formal

vista

presented

by

the

river.

Some

trifle

of

anxiety

might

mingle

with

this

gaze

at

the

first,

lest

perhaps Philistines might

be

abroad...

but

I

have

generally

found

that,

if

you

are

in

quest

of

some

certain

escape

from

Philistines

of

whatsoever

class-

sheriff-officers,

bores,

no

matter

what-

the

surest

refuge

is

to

be

found

amongst

hedgerows

and

fields,

amongst

cows

and

sheep..."

He went on to describe, in quite a comical passage, his terror at encountering for the first time the tidal phenomenon known as the Bore of the Dee:

"An affectation to which only some few rivers here and there were liable... so ignorant was I that, until that moment, I had never heard of such a nervous affection in rivers. Subsequently I found that the neighbouring river Severn, a far more important stream, suffered at spring-tides the same kind of hysterics..."

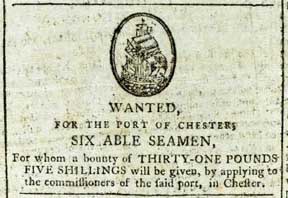

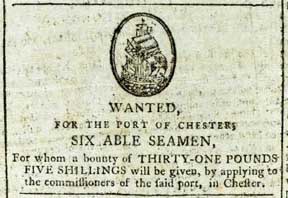

Colonel Robert Browne McGregor was an officer of the 88th regiment Connaught Rangers and stationed at Chester Castle in 1825 when he penned the following elegy for the declining fortunes of the River Dee and once-great Port of Chester: Colonel Robert Browne McGregor was an officer of the 88th regiment Connaught Rangers and stationed at Chester Castle in 1825 when he penned the following elegy for the declining fortunes of the River Dee and once-great Port of Chester:

How oft in my youth with a pleasing emotion,

When gladness was o'er me and pleasures increased,

Have I gaz'd on thy tide as it flowed from the ocean,

And bore on its bosom the wealth of the east.

Majestic and gay were the vessels adorning

Thy banks, lovely Dee! as I wandered along;

Where I loved to inhale the pure breath of the morning,

And listen with glee to the mariner's song.

How proudly I gaz'd on thy port that was crowded

With barks that were freighted from India's shore;

Nor thought of the time when thy hopes would be clouded,

And commerce and industry bless thee no more!

How changed are thy prospects, thou once lovely river!

The course of thy tide is perverted with sand;

Farewell to thy fame and thy glory- for never

Again shall a vessell be moor'd on thy strand?

Sweet stream- which the Druids in proud veneration

Have worshipp'd in ages, long vanished away,

Thou, theme of their story and deep adoration;

Deserted, neglected, art left to decay!

I stand on thy banks, in their beauty degraded,

And gaze on thy stream as it still murmurs on,

And sorrow to think that thy commerce is faded,

Thy splendour is tarnish'd- thy glory is gone! |

This somewhat disparaging description of Chester appeared in the London press- and was later reprinted in the local- in October 1825. Its writer is unknown. This somewhat disparaging description of Chester appeared in the London press- and was later reprinted in the local- in October 1825. Its writer is unknown.

"Chester is a town which is full of tit-bits for an antiquarian palate, but exceedingly ill-provided with the agreeabilities of the present day. Its character of virtue it can never lose, but many of the outward signs are fast going into decay, and what between the pulling down of old houses and the blocking up of the Rows, none but the antiquarian of the true Church will soon be able to recognise it. So ably is the hand of time seconded by the work of man, that the Board of Ordnance have now cased in fine cut stone Caesar's Tower, as it was called, one of the most perfect and prominent objects in the town".

(This presumably refers to the refacing of the medieval Agricola Tower during Thomas Harrison's rebuilding of the Castle). (This presumably refers to the refacing of the medieval Agricola Tower during Thomas Harrison's rebuilding of the Castle).

"The country in the neighbourhood, almost to the very walls, is beautiful in the extreme, but the first step within the gates gives the appearance of a doleful contrast which increases with every turn. The only place which appears to have been intended to unite the agreeable with the useful is the common jail. The inhabitants of that security are well clad, clean and comfortable, with well-flagged yards, while the streets are rudely paved with pointed stones and every ward has a snug flower garden before it.

There is no place of public amusement, but there is a capital bridge, and a rapid stream under it.

The great body of the people are strangely mixed up, of native English, stray Welsh, and imported Irish, and their voices, persons and language bear evidences of the ill-assorted compound. The Welsh is the most decided caste but Paddy has not been deficient, and, if one may judge by that distinctive attribute, a heavy heel, the fair sex are stamped with the marks of Milesian manufacture".

(After Milesius, legendary ancestor of the Irish people.)

"Jaunting cars, those most Irish and most convenient of one-horse vehicles, are numerous and very genteel moreover. But the most Irish concerns in Chester are the low, common public houses- the windows stuck full of red bills, the doors wide open to the street, and a crowd of ragged fellows, dram-drinking at the counters. When Chester was a garrison town, it was a gay and lively place, but politics have completely upset it.

The coach proprietors of Chester, aware of the disagreeabilities, afford strangers every every facility for quitting it. A steam boat goes to the mouth of the Dee and lands you on the Welsh coast for 9d; a coach from Liverpool to Oswestry through Chester takes you the whole way, 46 miles, for 3s 6d; and coaches from Chester to Liverpool, including the steam boat passage, 2s. Beware of the inns. Tea for one, "nothing with it", 2s; breakfast, a chop and one egg, 2s 6d."

The German Prince Herman Von Pückler-Muskau (1785-1871) visited Chester in late January 1827 as part of his tour of England. His collected letters to his ex-wife back in Germany were later turned into a book, Tour of a German Prince which made him into a minor celebrity in both countries. The German Prince Herman Von Pückler-Muskau (1785-1871) visited Chester in late January 1827 as part of his tour of England. His collected letters to his ex-wife back in Germany were later turned into a book, Tour of a German Prince which made him into a minor celebrity in both countries.

In addition to being a soldier, explorer, travel writer and noted womaniser, the prince was Germany's leading park designer and his main reason for spending the years 1826-8 in England was to find a wealthy bride in order to fund his grand landscaping projects. Whether he was successful in this I am unsure but the English-style Pückler-Muskau Gardens on the German-Polish border was the realisation of his life-long dream and is now a Unesco World Heritage site.

He visited Eaton Hall and was then shown around Chester Castle, of which he wrote,

"We visited the royal castle of Chester, which is now converted into an excellent county gaol. The whole arrangement of it seems to me most humane and perfect. The cells are clean and airy; the food varies with the degree of crime, the lowest is bread, potatoes and salt. Today, being New Year's Day, all the prisoners had roast-beef, plum-pudding and ale. "We visited the royal castle of Chester, which is now converted into an excellent county gaol. The whole arrangement of it seems to me most humane and perfect. The cells are clean and airy; the food varies with the degree of crime, the lowest is bread, potatoes and salt. Today, being New Year's Day, all the prisoners had roast-beef, plum-pudding and ale.

Most of them, especially the women, became very animated and made a horrible noise, with hurrahs to the health of the Mayor who had given them this féte.

The view from the upper terrace, over the gardens, the prison and a noble country, with the river winding below, just behind the cells; on the side, the roofs and towers of the city in picturesque confusion; and in the distance, the mountains of Wales- is magnificent, and á tout prendre (all things considered), our own country councillors of justice are seldom lodged as well as the rogues and thieves here".

Washington Irving (1783-1859), the American short story writer, essayist, poet, travel book writer, biographer, and columnist- best remembered today for his stories The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, in which the schoolmaster Ichabold Crane meets with a headless horseman, and Rip Van Winkle, about a man who falls asleep for 20 years- visited Chester around 1825 and recalled, Washington Irving (1783-1859), the American short story writer, essayist, poet, travel book writer, biographer, and columnist- best remembered today for his stories The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, in which the schoolmaster Ichabold Crane meets with a headless horseman, and Rip Van Winkle, about a man who falls asleep for 20 years- visited Chester around 1825 and recalled,

"I shall never forget the delight I felt on first seeing a May-pole. It was on the banks of the Dee, close by the picturesque old bridge that stretches across the river from the quaint little city of Chester. I had already been carried back into former days by the antiquities of that venerable place... the May-pole on the margin of that poetic stream completed the illusion. My fancy adorned it with wreaths of flowers and peopled the green bank with all the dancing revelry of May-day. The mere sight of this May-pole gave a glow to my feelings and spread a charm over the country for the rest of the day".

The composer Felix Mendelssohn (1809-47) made his first visit to England in 1829 and in September of that year stayed with the family of Mr John Taylor at Coed Ddu near Mold. Before arriving there, he paid a visit to Chester, which he described in a letter to his father, "A bright scene presented itself; the broad town walls made a promenade round the town and there I saw a girl's school marching along which I followed with my sketch book. The girls looked very pretty, the distance very blue, the houses and towers in the foreground dark grey". The composer Felix Mendelssohn (1809-47) made his first visit to England in 1829 and in September of that year stayed with the family of Mr John Taylor at Coed Ddu near Mold. Before arriving there, he paid a visit to Chester, which he described in a letter to his father, "A bright scene presented itself; the broad town walls made a promenade round the town and there I saw a girl's school marching along which I followed with my sketch book. The girls looked very pretty, the distance very blue, the houses and towers in the foreground dark grey".

The American poetess, Lydia Sigourney (1791-1865) visited Europe in 1840 and in the same year published in America her Pleasant Memories of Pleasant Lands, which was reprinted in England in 1843. From it, here is her graceful tribute to rare old Chester: The American poetess, Lydia Sigourney (1791-1865) visited Europe in 1840 and in the same year published in America her Pleasant Memories of Pleasant Lands, which was reprinted in England in 1843. From it, here is her graceful tribute to rare old Chester:

Queer, quaint, old Chester,—I had heard of thee

From one who, in his boyhood, knew thee well;

And therefore did I scan with earnest eye

The castled turret where he used to dwell,

And the fair walnut tree, whose branches bent

Their broad, embracing arms around the battlement.

His graphic words were like the painter's touch,

So true to life, that I could scarce persuade

Myself I had not seen thy face before,

Or round thine ancient walls and ramparts stray'd;

And often, as thy varied haunts I kenn'd

Stretched out my hand to thee, as a familiar friend.

Grotesque and honest-hearted art thou, sure,

And so behind this very changeful day,—

So fond of antique fashions, it would seem

Thou must have slept an age or two away.

Thy very streets are galleries and, I trow,

Thy people all were born some-hundred years ago! |

Old Rome was once thy guest, beyond a doubt,

And many a keepsake to thy hand she gave,—

Trinket, and rusted coin, and letter'd stone,

Ere with her legions she recross’d the wave;

And thou dost hoard her gifts with pride and care

As erst the Gracchian dame display'd her jewels rare.

There, 'neath thy dim cathedral, let us pause

And list the echo of that sacred chime,

That,when the heathen darkness fled away,

Went up at Easter and at Christmas time,—

Chants of His birth who woke the angel train,

And of that bursting tomb, where Death himself was slain.

Yes, in my simple garden,—far away,—

Beyond the ocean waves that toss and roll,—

Your gentle kindred drink the healthful ray,

Heaven's holy voice within their secret soul;

And the name words they speak, so pure and free,

Unto my loved ones there, that here ye say to me!" |

George

Borrow (1803-1881), linguist,

traveller

and

writer was born in Norfolk. His father was a soldier and moved throughout the British Isles taking his young son with him. His early apprenticeship to a solicitor suggested that a career in law was likely but Borrow took to literature and moved to London, notably editing Celebrated Trials and Remarkable Cases of Criminal Jurisprudence (1825). George

Borrow (1803-1881), linguist,

traveller

and

writer was born in Norfolk. His father was a soldier and moved throughout the British Isles taking his young son with him. His early apprenticeship to a solicitor suggested that a career in law was likely but Borrow took to literature and moved to London, notably editing Celebrated Trials and Remarkable Cases of Criminal Jurisprudence (1825).

Suffering not for the first or last time from manic depression, Borrow left London after about a year and began a lifelong pilgrimage around first England and then the continent (France, Germany, Spain, Russia and further east). Along the way, he made every effort to study the languages he came across and while in Spain and Russia he acted as an agent for the British and Foreign Bible Society.

Settling down in Oulton Broad, Suffolk and marrying a moneyed widow, Borrow began to write, documenting his experiences upon his travels. The Zincali, or an Account of the Gypsies in Spain (1841) and The Bible in Spain (1843) gave the author instantaneous success. His novel Lavengro (1851) is considered to be his masterwork, but The Romany Rye (1857) is also well regarded.

Here is an extract from chapter 68 of Lavengro, in which his characters discuss Chester Castle:

"Would you have me go to Chester and work there now? I don’t like the thoughts of it. If I go to Chester and work there, I can’t be my own man; I must work under a master, and perhaps he and I should quarrel, and when I quarrel I am apt to hit folks, and those that hit folks are sometimes sent to prison; I don’t like the thought either of going to Chester or to Chester prison. What do you think I could earn at Chester?"

Tinker:"A matter of eleven shillings a week, if anybody would employ you, which I don’t think they would with those hands of yours. But whether they would or not, if you are of a quarrelsome nature you must not go to Chester; you would be in the castle in no time". Tinker:"A matter of eleven shillings a week, if anybody would employ you, which I don’t think they would with those hands of yours. But whether they would or not, if you are of a quarrelsome nature you must not go to Chester; you would be in the castle in no time".

In 1854, Borrow embarked upon a walking tour of Wales- in whose language he had, remarkably,

become fluent as a young man. He recorded his experiences in his book Wild

Wales (1862). Here he describes the commencement of his journey in Chester...

"On

arriving

at

Chester

at

which

place

we

intended

to

spend

two

or

three

days,

we

put

up

at

an

old-fashioned

inn

in

Northgate

Street,

(

probably

the Pied

Bull)

to

which

we

had

been

recommended;

my

wife

and

daughter

ordered

tea

and

its

accompaniments,

and

I

ordered

ale,

and

that

which

always

should

accompany

it,

cheese.

"The

ale

I

shall

find

bad".

said

I;

Chester

ale

had

a

villainous

character

in

the

time

of

old

Sion

Tudor,

who

made

a

first-rate

englyn

upon

it,

and

it

has

scarcely

improved

since;

"but

I

shall

have

a

treat

in

the

cheese,

Cheshire

cheese

has

always

been

reckoned

excellent,

and

now

that

I

am

in

the

capital

of

the

cheese

country,

of

course

I

shall

have

some

of

the

very

prime."

Well,

the

tea,

loaf

and

butter

made

their

appearance,

and

with

them

my

cheese

and

ale.

To

my

horror

the

cheese

had

much

the

appearance

of

soap

of

the

commonest

kind,

which

indeed

I

found

it

much

resembled

in

taste,

on

putting

a

small

portion

into

my

mouth.

"Ah,"

said

I,

after

I

had

opened

the

window

and

ejected

the

half

masticated

morsel

into

the

street,

"those

who

wish

to

regale

on

good

Cheshire

cheese

must

not

come

to

Chester,

no

more

than

those

who

wish

to

drink

first

rate

coffee

must

go

to

Mocha.

1'll

now

see

whether

he

ale

is

drinkable,"

so

I

took

a

little

of

the

ale

into

my

mouth,

and

instantly

going

to

the

window,

spirted

it

out

after

the

cheese.

"Of

a

surety,"

said

I,

"Chester

ale

must

be

of

much

the

same

quality

as

it

was

in

the

time

of

Sion

Tudor,

who

spoke

of

it

to

the

following

effect:

"Chester ale, Chester ale! I could ne'er

get it down,

'Tis made of ground-ivy, of dirt, and of bran,

'Tis as thick as a river below a huge town !

'Tis not lap for a dog, far less drink for a man..."

"Upon

the whole we found ourselves very comfortable in the old-fashioned inn, which

was kept by a nice old-fashioned gentlewoman, with the assistance of three servants,

namely, a "boots" and two strapping chamber maids, one of which was a Welsh girl,

with whom I soon scraped acquaintance, not, I assure the reader, for the sake

of the pretty Welsh eyes she carried in her head, but for the sake of the pretty

Welsh tongue which she carried in her mouth, from which I confess occasionally

proceeded sounds which, however pretty, I was quite unable to understand...

On the morning after our arrival we went out together, and walked up and down

several streets; my wife and daughter, however, soon leaving me to go into a shop,

I strolled about by myself. Chester is an ancient town with walls and gates, a

prison called a castle, built on the site of an ancient keep, an unpretending-looking

red sandstone cathedral, two or three handsome churches, several good streets,

and certain curious places called rows. The Chester row is a broad arched stone

gallery running parallel with the street within the facades of the houses; it

is partly open on the side of the street, and just one story above it. Within

the rows, of which there are three or four, are shops, every shop being on that

side which is farthest from the street. All the best shops in Chester are to be

found in the rows. These rows, to which you ascend by stairs up narrow passages,

were originally built for the security of the wares of the principal merchants

against the Welsh. Should the mountaineers break into the town, as they frequently

did, they might rifle some of the common shops, where their booty would be slight,

but those which contained the more costly articles would be beyond their reach;

for at the first alarm the doors of the passages, up which the stairs led, would

be closed, and all access to the upper streets cut off, from the open arches of

which missiles of all kinds, kept ready for such occasions, could be discharged

upon the intruders, who would be soon glad to beat a retreat. These rows and the

walls are certainly the most remarkable memorials of old times which Chester has

to boast of."

"Upon the walls it is possible to make the whole compass of the city, there being a good but narrow walk upon them. The northern wall abuts upon a frightful ravine, at the bottom which there is a canal. From the western one there is a noble view of the Welsh hills." "Upon the walls it is possible to make the whole compass of the city, there being a good but narrow walk upon them. The northern wall abuts upon a frightful ravine, at the bottom which there is a canal. From the western one there is a noble view of the Welsh hills."

( You may read Borrow's conversation with a local regarding the name of one of

those hills by going here)

One final Borrow quote, upon a subject close to his heart, that of Cwru Da- good ale:

"Oh, genial and gladdening is the power of good ale, the true and proper drink of Englishmen! He is not deserving of the name of Englishman who speaketh against ale, that is good ale... and yet there are beings, calling themselves Englishmen, who say that it is a sin to drink a cup of ale... and exclaim, ‘The man is evidently a bad man, for behold, by his own confession, he is not only fond of ale himself, but is in the habit of tempting other people with it.’ Alas! alas! what a number of silly individuals there are in this world".

(Lavengro: chapter 68)

• The entire text of Wild Wales is freely available to read and download here. Highly recommended.

Thomas Hughes (1826-1890) was a man after our own hearts as he was the author, in 1856, of the Stranger's Handbook to Chester, a guide to our city which set the style for numerous later publications and to which we have frequently resorted during the research for our own Chester Virtual Stroll. Thomas Hughes (1826-1890) was a man after our own hearts as he was the author, in 1856, of the Stranger's Handbook to Chester, a guide to our city which set the style for numerous later publications and to which we have frequently resorted during the research for our own Chester Virtual Stroll.

Born in Chester, he attended the King's School, which was then housed in the old monk's refectory in the Cathedral.

Later in life, he became a governor of the school and founder of its old boys' association. He was a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, served as Sheriff of Chester and also as warden of the venerable St. John's Church, which was hisplace of worship for 30 years. His home was The Mount, a picturesque old house raised upon an embankment which formerly stood in St. Werburgh Street opposite the Cathedral and Music Hall. Just before it was demolished, he commissioned a picture of it from eminent local landscape artist Louise Raynor. (The site is today occupied by St. Werburgh's Row, built in 1935 and designed by Maxwell Ayerton, who was also the architect of the now-demolished Wembley Stadium, with its world-famous twin towers). His humble grave may, with some difficulty, be found in thick undergrowth in Chester's remarkable Overleigh Cemetery.

Perhaps better known outside Chester is another Thomas Hughes (1822-1896) who, a year after his namesake had pubished his Stranger's Guide, issued a novel which remains familiar today (or, perhaps, the classic film later made of it)- Tom Brown's Schooldays, written when he was 35.

Born in Berkshire, he attended Rugby School under its famous Head, Dr. Arnold, and later became a barrister, a Liberal MP and then, in 1882 he came to Chester at the age of 60 as a circuit judge. He had a grand turretted house built at 20 Dee Hills Park, overlooking the river, where he lived from 1885 until his death in 1896. His fine house (illustrated above left) remains with us today, a familiar sight to boaters on the River Dee and walkers on the Meadows.

In 1847, John Spence, "young physician", wrote Ship & Shore: or Pencil Sketches on a Recent Voyage. This excerpt describes his visit to Chester: In 1847, John Spence, "young physician", wrote Ship & Shore: or Pencil Sketches on a Recent Voyage. This excerpt describes his visit to Chester:

"Distant from Liverpool fifteen miles, is an ancient town called Chester, deserving the notice of the passing traveller. My young friend from Harvard and myself, on one occasion, turned our faces towards this venerable and antique town. You cross the river Mersey, by ferry, with a police-man at your elbow, scanning the motley throng of men, women, and children on board. Some of these police look intelligent; others are dull, corpulent, and sleepy fellows. As the boat touches the landing, the police is the first to step on shore, and stands at the toll-gate, to see if all deposit pennies for ferriage.

Procuring a ticket, and being seated in a rail-road carriage, or car, away we whirled. The country around was rich and well cultivated, vast quantities of bending and golden grain meeting the eye. Now and then we would pass a park, with its beautiful domains; and timid rooks would start on trembling wings, and then alight, dotting the green grass, or the trees, with dark and coal-black forms. The distance was soon traversed, and we were guests at the Albion Inn.

The plan of the city of Chester is simple. It is bounded by a wall which is said to have been built by the Romans. The walls are in the form of a parallelogram. The two main streets of the city intersecting each other at right angles, divide it into four equal portions. Other streets run into the main streets. The early history of the town of Chester dates far back. The ancient and time-worn appearance of the various buildings, as seen in the churches and cathedrals, indicates a very remote origin. Chester was the usual station of the twentieth Roman legion, and there are few cities in England, where, if the Roman soldiers were to return, they would find themselves more at home; for it belongs to the small and continually lessening number of those that have preserved an appearance of antiquity. Chester, like many English towns, seems to be in its dotage, while others given to manufactures resemble young giants. There is a College within the limits of the town, as is evident, by meeting now and then students winding through the streets. These were dressed in square caps and black flowing robes, and some of these latter were torn. They are rather more simple, primitive, and verdant students than one would meet with at Oxford and Cambridge Colleges- the alma; moires of some of England's master minds in days gone by, yet to produce minds their equals or superiors.

To what shall I liken the old city? It is not unlike old men. Old men, who wear their ages with a stoop, turtleshaped men- not mailed with horn to be sure, with lines encircling their shell, and golden dots drawn here and there- but men whose forms are thick-set; men whose hair is fleecy, while that which grows about the temples is of a silvery white; whose foreheads are traversed by ploughed lines, and harrowed all over; men who peer and leer through 'helps to read,' that are split purposely through the longest diameter; men who adjust these glasses on the lowest bridge of the nose, who, as they read, in actions say- standoff; paper keep your distance; men that wear silver knee-buckles, and buskins, and broad-brimmed hats, and cues that dangle down their backs; men that take snuff, first knocking for admittance with the knuckle on the pictured or highly chased silver lid; men that have fussy ways, and cough, and sneeze, and hem; men that forget the incidents of yesterday, and often call to mind those connected with boyhood and younger days. Not unlike such men, in some respects, is old Chester. It is not like the sanguine youth advancing to manhood, but akin to the aged veteran- the day of its pristine vigor having long since departed. Now and then, one meets a dilapidated lobided building, that looks cozy, and as though it were "nid nid nodding", its frame pinched and withered, and hoary age settled on it, its very windows seeming dimmed by age; it sustains the same relation to the surrounding houses, that a veteran in years, with shattered frame and wrinkled brow, and eyes that borrow glass to peer through, does to the wellknit frame of the buoyant youth. There are many of these aged buildings set down in different portions of the city; and they are like nothing else more, than like old men. Aged women and old men, one would think, should still move in antiquated homesteads. And it would seem as though the youth would "catch the living manners as they rise" and mould their characters and actions in the "glass of age", as seen in the peculiarities and antiquities of the town. To what shall I liken the old city? It is not unlike old men. Old men, who wear their ages with a stoop, turtleshaped men- not mailed with horn to be sure, with lines encircling their shell, and golden dots drawn here and there- but men whose forms are thick-set; men whose hair is fleecy, while that which grows about the temples is of a silvery white; whose foreheads are traversed by ploughed lines, and harrowed all over; men who peer and leer through 'helps to read,' that are split purposely through the longest diameter; men who adjust these glasses on the lowest bridge of the nose, who, as they read, in actions say- standoff; paper keep your distance; men that wear silver knee-buckles, and buskins, and broad-brimmed hats, and cues that dangle down their backs; men that take snuff, first knocking for admittance with the knuckle on the pictured or highly chased silver lid; men that have fussy ways, and cough, and sneeze, and hem; men that forget the incidents of yesterday, and often call to mind those connected with boyhood and younger days. Not unlike such men, in some respects, is old Chester. It is not like the sanguine youth advancing to manhood, but akin to the aged veteran- the day of its pristine vigor having long since departed. Now and then, one meets a dilapidated lobided building, that looks cozy, and as though it were "nid nid nodding", its frame pinched and withered, and hoary age settled on it, its very windows seeming dimmed by age; it sustains the same relation to the surrounding houses, that a veteran in years, with shattered frame and wrinkled brow, and eyes that borrow glass to peer through, does to the wellknit frame of the buoyant youth. There are many of these aged buildings set down in different portions of the city; and they are like nothing else more, than like old men. Aged women and old men, one would think, should still move in antiquated homesteads. And it would seem as though the youth would "catch the living manners as they rise" and mould their characters and actions in the "glass of age", as seen in the peculiarities and antiquities of the town.

There are two or three features in this town worthy of special remark. The side-walks are sheltered or enclosed in wooden frames, and form a part and portion of the buildings. They are elevated above the streets by an ascent arranged at intervals. A railing bounds the walks, and the stores are on a line with them. A person can walk these avenues completely sheltered from the storm and rain. Possibly, were walks like these in cities, the ladies would be gratified, and tradesmen pleased, especially in stormy weather. They are in technical language called "Rows." These alleys or walks are in keeping with the character of the whole town.

The walls are another interesting feature. They entirely surround the former limits of the town, extending a long distance. The stone or material is in blocks of a reddish sand color, and is much worn. A walk extends the whole length of the walls. Upon the outer limits rises a breastwork, and thus the walk is guarded, and might serve as a tower of observation. The distance from the inside of the walls to the ground varies in different places.

A stroll along these walls at the close of day is quite pleasant. Here the river Dee rolls along a smooth and silvery flood; farther on is seen a mill, and the hum and foaming rush of water that attends it is heard. There, as the last rays of the setting sun glance along and crimson the surface of the river, fishermen are seen dragging their wily nets, here, a bridge of noble architecture springs across and spans the river and farther on, the race-ground is seen. And here, within the circuit of the walls, is a barrack, looking like some old castle- and it is nothing else- where a regiment of England's standing army is quartered. The life led by soldiers, especially an indolent soldiery, is attended by much that is humiliating. They have few aspirations, save those awakened by the sound of the rolling drum, the beat to arms, or the clarion blast of the bugle, while others live and labor to sustain them. They create no capital, but consume and waste it. They guard nothing, but go through their routine performing an imaginary duty, as if forsooth they were effecting something, yet accomplishing nothing. The little time that is profitably occupied, leaves nearly the whole to be spent in idle roving, and the rounds of dissipation.

But to return: here rises to the view from the walls, a tower, where, history states, a king saw an army defeated; and there, is an old time-stained cathedral, that has withstood the brunt of winds, and the washing of fierce storms, years on years. Now like a dim spectre it meets the eye. Again, we stand far above the houses, that are within and beyond the limits of the walls, and now we meet a breach made by a rail-road, which encounters but to surmount every obstacle".

Printed

in

the

US Boston

Mirror in

June

1848 was

an

account

of

a

visit

to

Chester

by

one C. M. Kirkland.

Here

are

some

extracts... Printed

in

the

US Boston

Mirror in

June

1848 was

an

account

of

a

visit

to

Chester

by

one C. M. Kirkland.

Here

are

some

extracts...

"The

aspect

presented

on

entering

is

simply

that

of

an

old,

illbuilt,

narrow-streeted

town,

with

houses

leaning

over

the

pathway;

windows

of

every

conceivable

irregularity

of

size,

shape

and

position;

people

looking

quaint

enough

to

be

in

keeping

with

these

surroundings;

and

a

general

air

of

"the

world

forgetting

by

the

world

forgot"

about

it,

curious

enough

to

one

fresh

from

the

bustle

of

New

York.

The wall is not very obvious until one is absolutely upon it, for it is so hemmed

in, both inside and out, by houses, that it is only by chance that it appears

in its true character. The top is flagged, and kept beautifully clean and accessible

by numerous flights of steps, and furnishes one of the most beautiful walks

imaginable. The prospect from it is magnificent- on every side stretches England's

fairest and richest expanse of hill and dale; old towers, picturesque and overgrown

with ivy and wallflower, peep out here and there; in the background, far to

the south-west, lie the Welsh mountains, hoary in distance, all about your very

feet the crumbling walls of ancient churches, and the great cathedral, which

looks almost as old as the mountains. It is not reckoned among the fine ones

of England, but to us, fresh from staring new churches, it was very attractive.

The outside looked as if time would not spare it much longer; the stones are

so worn away by the weather that the outline is not only an undulating one,

but scalloped, to borrow a word from the dressmaker... One is apt to

suspect a painter of exaggerating in his outlines, but Chester cathedral would

lose nothing of romantic interest if represented by the daguerrotype.

It is really strange to see how the vicinity of true and noble antiquity puts

to shame all modern erections. We could find no other reason for the almost

contempt with which Eaton Hall- much sought after by travellers- inspired

us. This show-place, the principal seat of the Marquis of Westminister, looked

quite like a gothic toy of cardboard, after Chester... We wondered at the taste

which could erect a modern gothic villa almost under the walls of Chester. It is really strange to see how the vicinity of true and noble antiquity puts

to shame all modern erections. We could find no other reason for the almost

contempt with which Eaton Hall- much sought after by travellers- inspired

us. This show-place, the principal seat of the Marquis of Westminister, looked

quite like a gothic toy of cardboard, after Chester... We wondered at the taste

which could erect a modern gothic villa almost under the walls of Chester.

As you walk the streets, you see how romance was born in England. Instead of

great staring rows of houses, in the plan of whose fronts all shadow is excluded

as if it were death, we have upper stories projecting over the street and deep

recesses with only a railing in front where the families appear, at their various

occupations. It is as if the whole second storey were drawn back some ten or

twelve feet, leaving a shaded parlour without a front...

We do not expect to find any portion of England more characteristic and interesting

than Chester. It breathes of feudal times, and is enveloped in associations

of romance and poetry...

To

be

sent

to

West

Chester is

a

proverb quoted

in Notes

and

Queries in

1851:

"Passing

through

a

village

only

six

miles

from

London

last

week,

I

heard

a

mother

saying

to

a

child,

'If

you

are

not

a

good

girl

I

will

send

you

to

West

Chester.'" To

be

sent

to

West

Chester is

a

proverb quoted

in Notes

and

Queries in

1851:

"Passing

through

a

village

only

six

miles

from

London

last

week,

I

heard

a

mother

saying

to

a

child,

'If

you

are

not

a

good

girl

I

will

send

you

to

West

Chester.'"

Chester

was

commonly

known

as West Chester

during

the

18th

and

early

19th

centuries.

To

be

sent

hence

in

earlier

times

was

to

be

sent

into

banishment

i.e.

into

Ireland.

The following is an extract from A Vist to Europe in 1851 by Benjamin Silliman: The following is an extract from A Vist to Europe in 1851 by Benjamin Silliman:

We were soon at Chester, and in the city and its vicinity, being busily employed, we lingered until six in the evening. This town is venerable on account of its high antiquity, as it was coeval with the British, Roman, and Saxon times. It was long a Roman station, and is still inclosed completely by a wall, which is two miles in circuit; it is constructed of hewn stone, to the height of 20 feet, and several of the towers remain. We ascended one of these, the Phoenix, from which Charles I, in September, 1645, was a spectator of a battle, in which his troops were defeated at Marston Moor, or Waverton Heath, by the forces of the Parliament. Chester was loyal; it bravely sustained a siege of five months in the year 1647, and was finally reduced by famine and distress. In two months, more than 2000 of the inhabitants died from the pressure of the siege. It was civil war- brethren fighting against each other.

The walls of Chester are still entire, and our walk upon them gave us fine views of a very beautiful country; the river Dee, on which Chester stands, was at our feet, and the distant mountains of Wales on the northwest rose in misty grandeur. The town contains 25,000 inhabitants, the population being about that of our New Haven, but being inclosed within walls, it covers a much smaller area. It is, in general, well built; there are many modern houses, but most of them are in the old English style, and afford us interesting information as to the accommodations of the people, in centuries long past. The appearance is venerable; it is grotesque, and in general highly unarchitectural. The four gates of the city are on the site of the ancient Roman portals, and we ride into it under arches, that bestride the streets. Five Roman roads come to a centre here, and now five principal railways have their terminus in Chester.

The streets, corresponding to the modern gateways, run at right angles north and south. They were originally sunk by excavation far below the level of the ground, and the people crossed on arches. Although the ancient deep cutting is half filled up, we still, as we walk on the ground, see the people in their houses above the level of the street, although they are on what would usually be called the ground floor. The front of the houses in the lower story recedes, so as to present a continued portico, or piazza- a covered walk, through which the people freely pass, as in the streets of other towns. Still farther in and below are the shops, and the actual fronts of the dwelling houses give an air of freedom and sociability, very much in contrast with the closed doors and latticed and curtained windows of most other cities. It was amusing to us to walk along this covered and elevated thoroughfare, mingling with the people, and to pass from it familiarly into the open doors of the contiguous shops, situated beneath the second story of the houses, which project over them. Thus, in those parts of the town where this ancient arrangement is preserved, the pedestrians are completely protected from the weather. We afterwards saw a similar structure in Berne, and in Bologna.

Chester contains many relics of the Romans. The twentieth legion garrisoned Chester in the year 61 of Christ. Its name, from the Latin castrum (camp), recalls its Roman origin. Roman altars, coins, pottery, tiles with Roman stamps, tesselated pavements, baths and catacombs, attest a long possession of Chester by the Romans. It was evidently regarded by them as an important station. Chester contains many relics of the Romans. The twentieth legion garrisoned Chester in the year 61 of Christ. Its name, from the Latin castrum (camp), recalls its Roman origin. Roman altars, coins, pottery, tiles with Roman stamps, tesselated pavements, baths and catacombs, attest a long possession of Chester by the Romans. It was evidently regarded by them as an important station.

Roman Bath- Beneath the Feather Inn we entered, as through a cellar, into an excavation in the solid rock; it was supported by short pillars, and the place was so low that we were obliged to stoop in order to enter; the floor is still occupied by water, and there is a sudatory above, into which steam or heated air passed through holes in the vault of the lower room, where the heat was raised. The place which we saw was narrow and low, confined and disagreeable, and strongly contrasted with the luxurious baths, whose splendid ruins we afterwards saw in Rome.

A Crypt, of unknown antiquity, is on the opposite side of the street. We entered it through an underground room, which was occupied as a shop. The Crypt is 45 feet long, 15$ broad, and 11 high. It was a place of worship, as appears from a baptismal font of marble at the remote end of the room. It is in the Gothic style, but with round arches, and is in high preservation. It was a monastic building.

The Ancient Abbey And Cathedral- We visited the ancient Cathedral and Abbey, objects of extreme interest to our party, none of whom, myself excepted, had ever seen such buildings. The Cathedral is 372 feet long on the outside, 350 within; height of the ceiling 73 feet, and of the towei 127. It has a fine organ, and numerous sepulchral monuments ; its cloisters are deservedly celebrated. Among the images, some had lost their heads by violence or wantonness, and an unskilful mason repaired them with so little tact that a King's head was placed upon a queen's shoulder, and the reverse, and a monarch crowned the bust of a virgin. These structures are extremely venerable from age, and association with gone by centuries; and perhaps our veneration is increased by the state of dilapidation in which they now exist. They and other ancient buildings in Chester were constructed of a deep-colored red sandstone, which exists in this part of England; it is the upper red belonging to the salt formation, and exfoliates in the weather, so that most of the ornamental carved work on the Cathedral and in the cloisters, especially that on the exterior, is defaced, or utterly ruined; many of the prominent parts have fallen off.

Miscellaneous- Probably no city in England presents such striking proofs of antiquity as Chester. It is so identified with antiquity, that while there we can easily imagine ourselves cotemporary with the Romans, with the Britons, and the Saxons. Chester was formerly a place of great trade, long before Liverpool had even a name to live; but the filling up of the channel of the Dee with sand, and the rivalry of Liverpool, have caused it to decline. Chester exhibits in its bill of mortality decisive proof of the salubrity of its position. The deaths are annually 1 in 40, while Liverpool loses 1 in 27, Manchester 1 in 28, Edinburgh 1 in 20, London 1 in 20; New Haven, in Connecticut, loses 1 in 55.

The Palace of the Marquess of Westminster- This splendid establishment is four miles from Chester, and our party drove to it in two cabs or flys, as they are often called here ; they were large and heavy, far more so than our light vehicles in America. These English carriages, being well cushioned on all sides, and lighted by large glass windows, are both very agreeable and comfortable. As before remarked, in Liverpool they place four persons in them, and occasionally there is, as was the case to-day, an extra man on the box with the coachman. The carriage took six persons with one horse. They work their horses much harder than we do in America. The climate being more temperate, perhaps the horses are more hardy.

The Castle- We passed out of the city by the castle, the ancient seat of the Earls of Chester. It was originally built by William the Conqueror. The old castle was removed near the close of the last century, and the present grand edifice was erected; it is Grecian, is 103 feet long and 35 broad, and is surrounded by a fosse, 13 feet deep, cased with hewn stone. The Castle- We passed out of the city by the castle, the ancient seat of the Earls of Chester. It was originally built by William the Conqueror. The old castle was removed near the close of the last century, and the present grand edifice was erected; it is Grecian, is 103 feet long and 35 broad, and is surrounded by a fosse, 13 feet deep, cased with hewn stone.

Most of the buildings connected with the castle are massy and grand, and are in modern style. A garrison of some hundreds of soldiers is stationed there, and they were on parade to-day, as we drove by, presenting the usual brilliant appearance of British troops.

The Race Ground, Called Roodee- This ground, covering 84 acres of rich meadow land, lies contiguous to the road. It is a beautiful natural amphitheatre, in a deep depression, surrounded by hills, by the city walls, and the river Dee, in the form of a bow arching outward. The exterior circle, in which the horses run, is one mile and a half to two miles in circumference, and is separated from the general area within by a low circular mound of earth. The English gentry are very fond of the turf, and this is said to be second to none in the kingdom. In 1848, 156 horses were entered for the tradesman's cup, and 106 accepted, being the largest number ever known for one race, here or elsewhere. Thirty-four horses started for the rich prize, which was won by a horse called Peep-o'day Boy; he swept the stakes, amounting to 2,500 pounds, more than 12,000 dollars.

Eaton Hall, The Seat Of The Marquis Of Westminster- Passing the race ground, we soon arrived at the portal of the domain of the Marquis of Westminster, two or three miles from the palace. As we drove up to the gate, an elderly man, of very respectable appearance, presented himself, and we asked permission to drive into the park. He civilly replied that it was not, at present, permitted, as the mansion was undergoing repairs. But upon my telling him that we had come from a far distant country, America, that we were in pursuit of knowledge, that this was our occupation at home, and was our sole object in Europe, he added, in a courteous manner, that, as wo had come so far, we should pass.

We drove on, mile after mile, before we reached the magnificent mansion. Through much of the territory every thing, except the road, and some occasional spaces, was in an unsubdued state, as much so as in an American wild, where the first forest had been cleared away, and a new growth of smaller trees had arisen spontaneously. Perhaps this half-wilderness appearance was the result of design, for on both sides, beyond this double row of woods, there was a parallel extent of subdued and cultivated land, smooth with green sward, and on these fields, as well as in other parts of the vast territory, there were innumerable herds of deer grazing quietly, along with flocks of sheep, and they were not, any more than the latter, disturbed by our approach. Arrived at the mansion, we were very civilly conducted through the extensive conservatories and fruit gardens, which we found to be highly interesting and instructive. There were many flowering shrubs and plants, both exotic and native, in the warm glass houses; one was devoted to pine-apples, which were in healthful progress, and some of them were beginning to put forth fruit.

The orchideae were numerous and flourishing. Being parasite plants of many species, they were growing in connection with suspended pieces of trees, and were depending from pots and from bunches of moss and peat. In the conservatories there was a beautiful contrivance for opening and shutting the glass, all at one movement and by a single effort of the hand. There is a very extensive provision for wall fruit. Large areas, which might be called fields, are inclosed by high brick walls, upon which are trained, in the most beautiful manner, peach trees, pears, and I believe apricots, branching out like rays of light from a focus, and extending to a surprising length —so that, in some places, the branches would mount above the wall, were they not bent and made to take another and lower direction. It is thus, that here in England, in more than 53° of north latitude, six degrees north of Quebec, and even as high as Hudson's Bay, tropical fruits are matured in perfection, and those of our American climates are reared to a surprising degreo of excellence. I remember that when I was in this country before, I tasted at a dinner in London, the most delicious pine-apple that I had ever seen, and it was the production of an English hot-house.

Tho territory around the mansion was muddy, as there is in this climate much rain from the condensed vapor of the Atlantic, and our walks through the grounds were on that account rather inconvenient. The 20th of March, too, is rather an early day to expect dry ground in any northern climate, either in Europe or America. Even at the vernal equinox, and in this high latitude, the grass is of a rich green, the shrubs and smaller trees are in leaf, of this season's growth, and many more are in flower in the open air.

And now, what shall I say of this immense and magnificent mansion, built in the style of the modern Gothic, with numerous turrets, pinnacles, and towers. I have no tables of its dimensions, but presume that, with the offices, it cannot be less than 400 feet long. Drawings and pictures are necessary to make the elevation intelligible. This palace, for it well deserves that name, is both grand and beautiful. The main front looks east towards the Dee, which flows through the territory; and the grounds slope downward from the mansion towards the river. They are laid out in ornamental forms, and are in good progress towards perfection, although there is still much to be done. It is obvious that when finished, covered by rich verdure, and decorated with the usual embellishments of English gardening, these grounds will be worthy of the palace which they surround and adorn. Urns, embossed with raised figures, are distributed here and there, and a small temple covers a Roman altar, dug up at Chester. It is a square pillar of red sandstone, about five feet high, 18 or 20 inches in diameter, and the top is scooped out like a dish, probably to contain the things offered in sacrifice. The Latin inscription on the side is perfectly legible. The altar is inscribed to the Nymphs and the Fountains, by the Twentieth Legion. "Nymphis et Fontibus Leg. xx w"- with the modest addition- " the victorious and invincible."

Eaton Hall being now occupied by artists and workmen, who are finishing and fitting up the apartments, we could not be admitted into the interior- but through the magnificent windows, which we were allowed to approach, we could see such apartments as were lighted by them. The furniture is removed, and we could catch only glimpses of grandeur and gorgeous embellishment. The front windows are very lofty, and adorned by painted glass; their cost was enormous. Eaton Hall is warmed uniformly by the circulation of hot water in tubes. At the opposite ends of the vast portico, stand two large marble statues; one is an undraped female, and the other a knight in full armor. This villa is, I believe, not surpassed in magnificence hy any one in England, and its noble master is said to be only the second in opulence- yielding, I presume, in this respect, to the Duke of Northumberland. The late Marquis of Westminster stood godfather to Queen Victoria at her coronation, and her eldest son, the Prince of Wales, is also Earl of Chester. We had to regret that it was impossible to obtain access to the library room, which is the largest and most magnificent apartment in the house, and contains a valuable collection of books and manuscripts. Eaton Hall being now occupied by artists and workmen, who are finishing and fitting up the apartments, we could not be admitted into the interior- but through the magnificent windows, which we were allowed to approach, we could see such apartments as were lighted by them. The furniture is removed, and we could catch only glimpses of grandeur and gorgeous embellishment. The front windows are very lofty, and adorned by painted glass; their cost was enormous. Eaton Hall is warmed uniformly by the circulation of hot water in tubes. At the opposite ends of the vast portico, stand two large marble statues; one is an undraped female, and the other a knight in full armor. This villa is, I believe, not surpassed in magnificence hy any one in England, and its noble master is said to be only the second in opulence- yielding, I presume, in this respect, to the Duke of Northumberland. The late Marquis of Westminster stood godfather to Queen Victoria at her coronation, and her eldest son, the Prince of Wales, is also Earl of Chester. We had to regret that it was impossible to obtain access to the library room, which is the largest and most magnificent apartment in the house, and contains a valuable collection of books and manuscripts.

There is here, beneath a glass case, a Torques- " a collar or chain of gold and silver, given by the Romans to soldiers who had distinguished themselves; they were wreathed with great heauty, and worn around the neck." It is conjectured that this ornament might have belonged to Queen Boadicea, as it was found on the ground between Caerwys and Newmarket in Flintshire, where it is supposed a decisive battle between Agricola and Boadicea took place, in which the latter lost 10,000 men. An unhewn stone is believed to designate the grave of Boadicea".

Nathaniel

Hawthorne, author

and

US

consul

in

Liverpool,

visited

Chester

in

1853

and

said

"I

must

go

again

and

again

to

Chester,

for

I

suppose

there

is

no

more

curious

place

in

the

world." Nathaniel

Hawthorne, author

and

US

consul

in

Liverpool,

visited

Chester

in

1853

and

said

"I

must

go

again

and

again

to

Chester,

for

I

suppose

there

is

no

more

curious

place

in

the

world."

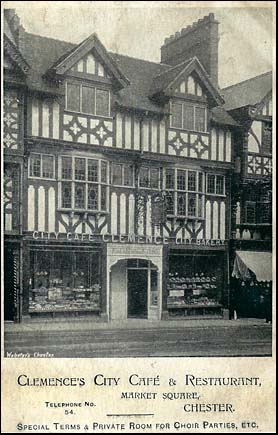

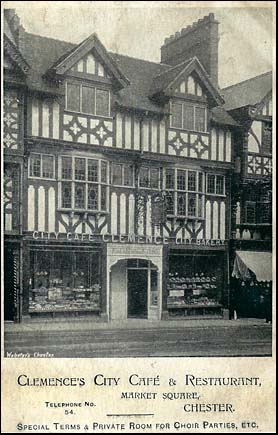

Celebrated

author

of Moby

Dick, Herman

Melville visited

while

staying

with

Hawthorne

in

1856

and

partook

of

a

"very

comfortable

meal"

upstairs

in

the

Rows

in

"an

antique

room

fronting

onto

the

street...

with

a

good

fire"

and

some

"Bass's

ale." Celebrated

author

of Moby

Dick, Herman

Melville visited

while

staying

with

Hawthorne

in

1856

and

partook

of

a

"very

comfortable

meal"

upstairs

in

the

Rows

in

"an

antique

room

fronting

onto

the

street...

with

a

good

fire"

and

some

"Bass's

ale."

Melville's

less well known

early

novel Redburn (1849)

vividly

recalls

his

experiences

as

a

boy

sailor

thirty

years

earlier

during

a

voyage

from

New

York

to Liverpool (a

few

miles

from

Chester)

and

of

his

wanderings

through

the

town

during

the

weeks

his

ship,

the Highlander,

was

berthed

there.

You

can

read

his

fascinating

description

of

Prince's

Dock Here.

On

to

more Nineteenth Century traveller's

tales

of

Chester...

|

![]() G. H. Steele visited

Chester

in

the

course

of

a

short

tour of

Lancashire,

Cheshire

and

North

Wales.

Little

is

known

of

him,

except

that

he

was

born

in

Prenton

on the Wirral about

1791,

and

was

apparently

living

in

London

when

he

wrote

his

account

of

the

tour.

This

extract

is

dated

Tuesday,

18th

August

1818...

G. H. Steele visited

Chester

in

the

course

of

a

short

tour of

Lancashire,

Cheshire

and

North

Wales.

Little

is

known

of

him,

except

that

he

was

born

in

Prenton

on the Wirral about

1791,

and

was

apparently

living

in

London

when

he

wrote

his

account

of

the

tour.

This

extract

is

dated

Tuesday,

18th

August

1818...![]() John Marsh (1752–1828) was an English music composer, born in Dorking, England. He was was perhaps the most prolific English composer of his time and is known to have written at least 350 compositions, including at least 39 symphonies. Of these, only the nine that Marsh had printed are extant, together with three one-movement finales. Marsh was a man of varied interests, and his 37 volumes of journals are among the most valuable sources of information on life and music in 18th-century England.

John Marsh (1752–1828) was an English music composer, born in Dorking, England. He was was perhaps the most prolific English composer of his time and is known to have written at least 350 compositions, including at least 39 symphonies. Of these, only the nine that Marsh had printed are extant, together with three one-movement finales. Marsh was a man of varied interests, and his 37 volumes of journals are among the most valuable sources of information on life and music in 18th-century England. ![]() Thomas

De

Quincey, the

'English

Opium

Eater',

frequently

came

to

Chester

to

'dry

out'

and

in

order

to

evade

creditors

and

officers

of

the

law.

His

mother

lived

in

a

house

known

as

'The Priory',

situated

among

the

now-vanished

ancient

buildings

adjoining St.

John's

Church. De

Quincey

wrote

the following about

his

wanderings

near

the

river

Dee

in

his

great Confessions of

1821:

Thomas

De

Quincey, the

'English

Opium

Eater',

frequently

came

to

Chester

to

'dry

out'

and

in

order

to

evade

creditors

and

officers

of

the

law.

His

mother

lived

in

a

house

known

as

'The Priory',

situated

among

the

now-vanished

ancient

buildings

adjoining St.

John's

Church. De

Quincey

wrote

the following about

his

wanderings

near

the

river

Dee

in

his

great Confessions of

1821: "The

streets

could

be

evaded

by

shaping

a

course

along

the

city

walls;

which

I

did,

and

descended

into

some

obscure

lane

that

brought

me

gradually

to

the

banks

of

the

river

Dee.

In

the

infancy

of

its

course

amongst

the

Denbighshire

mountains,

this

river,

famous

in

our

pre-Norman

history

for

the

earliest

parade

of

English

monarchy

(it

was

a

very

scenical

parade,

for

somewhere

along

this

reach

of

the

Dee,

Edgar,

the

first

sovereign

of

all

England,

was

rowed

by

nine

vassals reguli) -is

wild

and

picturesque,

and

even

below

my

mother's

Priory

it

wears

a

character

of

interest.

But,

a

mile