|

he writer and traveller John Lawson Stoddard was born in Brookline, Massachusetts in 1850. After some years teaching, in 1874 he began traveling around the world and turned his experiences into a series of popular lectures delivered throughout North America. These lectures were periodically published in book form as John L. Stoddard's Lectures. The books were immensely popular in their day and many copies still survive. In 1901 he got his first impressions of 'Old England' during a visit to Chester… he writer and traveller John Lawson Stoddard was born in Brookline, Massachusetts in 1850. After some years teaching, in 1874 he began traveling around the world and turned his experiences into a series of popular lectures delivered throughout North America. These lectures were periodically published in book form as John L. Stoddard's Lectures. The books were immensely popular in their day and many copies still survive. In 1901 he got his first impressions of 'Old England' during a visit to Chester…

"It was on a beautiful afternoon in May, soon after my first landing in Liverpool, that I caught sight of the old town of Chester on the river Dee. In the immediate foreground was a massive bridge built, by King Edward I, two hundred years before Columbus gazed upon the shores of the New World. As I look back upon it now, through a long vista lined with the more ancient monuments of Italy, Asia Minor, India, and Egypt, I wonder at the impression which this structure made upon me. But it was my first sight, then, of any genuine relic of past centuries; and the mere thought that these old arches had supported Queen Elizabeth, Charles I, Cromwell, and scores of other royal or distinguished characters gave me my first experience in realizing history, which is, perhaps, the greatest charm of foreign travel. But these impressions sank into comparative insignificance as, on our way to the hotel, we passed an ancient tower, carefully restored. Beside this monument, even the bridge of Edward I seemed modern; since this once formed a part of the old walls of Chester, and its foundations are a relic of imperial Rome. Chester was, in fact, for four hundred years, a Roman stronghold of such value that, as its name denotes, it was called simply Cas-trum, or "The Camp," - much as old Rome herself was proudly named, as if that single title were sufficient, Urbs, "The City." We cannot, therefore, be surprised to learn that in its soil coins, inscriptions, altars, and mosaic pavements have been found, all dating from the time when a word uttered on the Palatine was obeyed in Britain, and Rome was still the mistress of the world.

I know of nothing precisely like the walls of Chester. The Kremlin battlements in Moscow may suggest them; but the old Russian towers have summits almost inaccessible, while these thick walls of Chester enclose the town in one continuous ring, and form a well-paved promenade, nearly two miles in circuit and in some places forty feet in height. How stirring are the memories which they suggest! Here, for centuries, while the young Christian Church with tears and prayers was burying its martyrs in the catacombs, the soldiers of the Caesars kept their watch and ward above the town below, till the eventful day when Rome's imperial legions were called back to Italy, to ward off the alarming blows struck by barbarians at the Empire's heart. Upon the surface of one of these turrets, also, I read the inscription: "Upon this tower, Sept. 27, 1645, stood King Charles I, and saw his army defeated on Rowton Moor." For Chester ("loyal Chester", it was then called) was the first English city to declare for Charles, and the last to yield to Cromwell; and it was with the bitter consciousness that the last gem was being taken from his coronet of faithful towns, that the unhappy monarch (himself so soon to suffer death) saw from this tower his gallant cavaliers borne down by the fierce squadrons of the Puritans.

I never saw more curious architecture, even in the oldest towns of Germany, than that of some of Chester's streets. A score of times I said, regretfully, "Why did not Dickens give to these odd passageways some of his inimitable descriptions?" He, of all writers, would have fairly reveled here. Thus, some of the houses have to lean against their neighbors for support, as if too weak to stand alone, or out of breath from their long race with Time. Their very foundations seem to have shrunk away, like the limbs of a paralytic, and look as if they might collapse at any moment and let the superstructure fall.

Still more extraordinary than these, however, are Chester's covered sidewalks. Their sombre hue and well-worn steps attest their great antiquity, and it is interesting to learn that they are supposed to follow exactly the lines of the original Roman thoroughfares. They are called "Rows", but certainly not because of any perfume here of Jacqueminots. By any name they would smell no more sweetly; for musty odors haunt these low-browed corridors, and damp, unsavory smells creep out from the old planks and flagstones never gilded by the sun. Yet in these shadowy arcades are many handsome shops, above which frequently dwell the tradesmen's families. One of the houses surmounting these sidewalks has a more juvenile appearance than its neighbors, since it was reconstructed thirty years ago. Upon the sill, however, just above the corridor, I read the ancient inscription: "God's Providence is my inheritance." Is it possible that these words betray the owner's disappointment on coming into possession of this residence? Apparently he had more faith in Providence than in the value of the premises. I fancy that his sentiments must have been, "God only knows what I am going to realize from this property." A friend of mine, who had invested heavily in Western farm mortgages here turned his face to the wall and wiped away a tear. It is claimed, however, that this inscription denotes the owner's gratitude to Providence for having spared his dwelling during the ravages of the plague in Chester two hundred years ago".

The distinguished novelist Henry James (1843-1916), was born in America but spent much of his life in Europe. This passage from his "most perfect" novel The Ambassadors (1903) is expressive of his affection for Chester and all things English- he became a naturalised Englishman just before his death. The distinguished novelist Henry James (1843-1916), was born in America but spent much of his life in Europe. This passage from his "most perfect" novel The Ambassadors (1903) is expressive of his affection for Chester and all things English- he became a naturalised Englishman just before his death.

(Oscar Wilde, however, remarked of his literary style, "Mr Henry James writes fiction as if it were a painful duty")...

"The tortuous wall-girdle, long since snapped, of the little swollen city, half held in place by careful civic hands, wanders in narrow file between parapets smoothed by peaceful generations, pausing here and there for a dismantled gate or a bridged gap, with rises and drops, steps up and steps down, queer twists, queer contacts, peeps into homely streets and under the brows of gables, views of cathedral tower and waterside fields, of huddled English town and ordered English country..."

"It is still an antique town, and medieval England sits bravely under her gables" So he wrote years before creating 'Ambassador' Strether strolling on Chester's wall, admiring the Cathedral and "the first swallows of spring".

James himself was was also inspired by the Cathedral, writing of "the vast oaken architecture of the choir stalls, climbing vainly against the dizzier reach of the columns".

In 1903, T. A. Coward published his book Picturesque Cheshire; a glowing account of the county in the closing days of the nineteenth century.

Here are a couple of extracts dealing with the city of Chester: In 1903, T. A. Coward published his book Picturesque Cheshire; a glowing account of the county in the closing days of the nineteenth century.

Here are a couple of extracts dealing with the city of Chester:

"A mile from Hoole I enter Chester- Chester, the ancient city, capital of Cheshire and practically of North Wales; Chester, beloved by Americans; Chester, the centre of all historical interest in the County Palatine.

The men of Chester are proud of their ancient home; they love its quaint street rows, and lath and plaster buildings, its cathedral, its ruined church, its Roman baths and houses. Chester to-day, save that the streets are wider and lined with tram lines and that electric light illuminates dark corners, looks much as it did in mediaeval days. No one dare nowadays erect a plain brick building or an ugly factory within the city; the modern buildings are all half-timbered, black and white; it is not always easy at first sight to distinguish between a new shop or house and the freshly painted timbers and clean new whitewash of some timehonoured mansion.

The Rows, the raised sidewalks with shops within and shops below, for which Chester is famous, are rebuilt and repatched whenever time threatens their stability; the city walls that gird the centre of the town are kept in perfect order...

Of Chester, Lucian, the monk, wrote about the twelfth century: "And whilst it casteth an eye forward into the East; it looketh towards not only the See of Rome, and the Empire thereof, but the whole world also, so that it standeth forth as a kenning place to view of eyes, that there may be known valiant exploits, and the long train and consequence of things." "which city having gates from four cardinal winds, on the east-side hath a prospect towards India, on the west toward Ireland, north-eastward the greater Norway, and southward that straight and narrow Angle, which divine severity, by reason of civil and home discords, hath left unto the Britons."

Sleepy Chester! Looking out towards the whole world as a kenning place! Yes, perhaps; but say rather, Sleeping Chester! Chester, the city of the dead, Chester the Ancient. Older than busy, bustling Manchester; older by far than that huge city of Birmingham; a seaport whose fleets traded with the world when the great Port of Liverpool was but a handful of hovels beside the Mersey pool. A most ancient, hoary-headed city compared with your huge Metropolis, oh ye quizzical Americans! though to do you justice, you know how to appreciate its history and relics of the past.

One word more. When that ponderous lexicographer, Dr Johnson, closed his description of Chester in 1774, he remarked: "Chester has many curiosities." Indeed it has!

A curious news item, which appeared in the New York Times, September 13th 1913, described how a wealthy American collector, Mr Henry C Frick, had acquired, in addition to a rare 17th century organ, "some remarkable specimens of carved woodwork from a room of a house in Chester. The woodwork, which is now crossing the Atlantic, came from one of the houses in The Rows. The room it adorned was designed by Sir Christopher Wren at the request of the municipality for the city's mayor. The purchaser, Karl J Freund, a New York Dealer, who is now in Paris, feared to announce the purchase of the doors, panelling and wainscotting while the woodwork was still in England, fearing that legal means might be devised to prevent their exportation to the United States. The carvings are extraordinary. Their grace and richness are said to surpass even those of the great show-rooms at Hampton Court." A curious news item, which appeared in the New York Times, September 13th 1913, described how a wealthy American collector, Mr Henry C Frick, had acquired, in addition to a rare 17th century organ, "some remarkable specimens of carved woodwork from a room of a house in Chester. The woodwork, which is now crossing the Atlantic, came from one of the houses in The Rows. The room it adorned was designed by Sir Christopher Wren at the request of the municipality for the city's mayor. The purchaser, Karl J Freund, a New York Dealer, who is now in Paris, feared to announce the purchase of the doors, panelling and wainscotting while the woodwork was still in England, fearing that legal means might be devised to prevent their exportation to the United States. The carvings are extraordinary. Their grace and richness are said to surpass even those of the great show-rooms at Hampton Court."

Remarkable stuff. This is the first we've heard of the great Wren having designed anything in Chester. Who knows, perhaps it was merely a 'clever bit of patter', all the better to impress a 'gullible Yank' and boost the price? Should any of our American friends know of what became of the panelling, we'd love to hear about it!

Best

remembered

for

his 'In

Search

of'

books,

the

prolific

travel

writer H. V. Morton published

his In

Search

of

England in

June

1924.

From

it,

here

is

his

evocative record

of

a

visit

to

Chester: Best

remembered

for

his 'In

Search

of'

books,

the

prolific

travel

writer H. V. Morton published

his In

Search

of

England in

June

1924.

From

it,

here

is

his

evocative record

of

a

visit

to

Chester:

"Well and truly was Chester called by the Britons Caer Lleon, the 'City of the Legions'. Chester is still the 'City of the Legions', only they now come from Louisville, and Oshkosh, New York, and Washington.

For years I have heard people decribe the wonder of a walk round the walls of Chester. Naturally the first thing I did when I arrived here was to find the wall, which is not difficult. Chester, as you must know, is the only city in England which retains its medieval wall complete: a high red sandstone walk with towers at various strategic points along its course; on one side a handrail to prevent you from falling into back gardens, on the other a waist-high barrier from which in old times the Cestrians were in the habit of defying their enemies with boiling oil-and anything else that came handy. 'Blessed is he that expecteth little ' is a wise maxim that has been drummed into me since I first sat up and wanted the moon; but I have never absorbed it. I realized this on the walls of Chester.

Any man might with justice, I think, expect that as he walked a medieval town wall something at least heroic would meet his eye, but the walls of Chester gave me only a much better idea of other people's washing, the gas-works, and the canal. You see Chester within the wall remains medieval, but Chester outside the wall is industrial. It has not been possible, with factory sites at one hundred and thirty pounds an acre, for Chester to retain a wide, open space outside the wall, and, consequently, the wall of Chester stands with its arms round beautiful old Chester, while ugly new Chester peeps over the parapet from the other side.

I had been walking for about ten minutes, admiring the small, reddy-brown cathedral

through the trees, when I came to a turret approached by a flight of ancient steps, and on the wall was this dramatic inscription:

KING CHARLES

STOOD ON THIS TOWER

SEPTEMBER 24th, 1645, AND SAW

HIS ARMY DEFEATED

ON ROWTON MOOR

Inside

the

tower

a

man

was

presiding

over

a

little

museum.

He

told

me,

just

as

though

he

was

present

at

the

time,

that

when

the

Royalist

army

was

riding

to

reinforce

the

garrison

at

Chester,

the

Roundheads

set

upon

them

and

routed

them

with

poor

King

Charles

standing

on

this

tower

watching

every

move

of

the

game.

There

are

various

battlefield

relics

in

the

museum,

also

several

Roman

antiquities

which

take

the

mind

back

to

the

days

when

that

magnificent

Legion,

the

20th,

known

as

the

'Valeria

Victrix',

was

the

crack

regiment

of

Deva.

I

had

been

walking

for

miles,

wondering

if

the

wall

of

Chester

ever

completes

its

circle,

when

I

came

to

that

which

any

exhausted

visitor

must

regard

as

a

poor

joke.

Here,

near

Bridge

Gate,

is

a

long

flight

of

steps

arranged

in

sets

of

three

and

known

as

the

'Wishing

Steps'.

'Why?'

I

asked

a

man

who

was

standing

on

them,

looking

as

though

none

of

his

wishes

had

ever

come

true.

'Well,'

he

said,

in

the

curiously

blunt

way

they

have

here,

'you

have

to

run

up

and

down

and

up

again

without

taking

breath,

and

then

they

say

you'll

get

your

wish.'

I

noticed

a

band

of

breathless

Americans

standing

on

the

other

side,

utterly

vanquished.

I

decided

to

try

no

conclusions

with

the

Wall

of

Chester

and

passed

on

in

a

superior

way,

mentally

deciding

to

have

a

wish-

for

I

can

never

resist

these

challenges

of

Fate-

some

morning

when

I

could

come

fresh

and

vigorous

to

the

steps.

That,

however,

I

learn

is

not

playing

the

game;

you

must

walk

the

wall

first

and

then

'run

up

and

down

and

up

again',

a

feat

which

I

shall

leave

to

the

natives-

and

to

the

Legions! I

noticed

a

band

of

breathless

Americans

standing

on

the

other

side,

utterly

vanquished.

I

decided

to

try

no

conclusions

with

the

Wall

of

Chester

and

passed

on

in

a

superior

way,

mentally

deciding

to

have

a

wish-

for

I

can

never

resist

these

challenges

of

Fate-

some

morning

when

I

could

come

fresh

and

vigorous

to

the

steps.

That,

however,

I

learn

is

not

playing

the

game;

you

must

walk

the

wall

first

and

then

'run

up

and

down

and

up

again',

a

feat

which

I

shall

leave

to

the

natives-

and

to

the

Legions!

There

is

one

feature

of

Chester

which,

to

my

mind,

is

worth

ten

walls.

There

is

nothing

like

it

in

any

English

town- the

Chester

'Rows'. Watergate Row North by Louise Raynor (1832-1924). You can see many more of her Chester paintings here.

Chester

is

a

town

of

balconies.

The

first

impression

I

received

of

it

was

a

town

whose

inhabitants

spend

a

great

portion

of

their

lives

leaning

over

old

oak

galleries,

smoking

and

chatting

and

watching

life

go

by

below

them

in

the

streets.*

'The

Rows'

are

simply

long,

covered

arcades

formed

by

running

a

highway

through

the

first

stories

of

a

street

of

old

buildings.

You

mount

from

the

roadway

to

'the

Rows'

on

frequent

flights

of

stone

steps

and

find

yourself

in

the

strangest

shopping

streets

in

England.

Here

are

the

best

shops

hidden

away

in

the

darkness

of

these

ancient

arcades,

and

it

is

possible

to

shop

dry-shod

in

the

worst

weather.

There

is

a

peculiar

charm

about

'the

Rows'.

They

are

not

typically

medieval,

because

there

is

no

record

of

any

other

street

of

this

kind

in

the

Middle

Ages,

yet

they

impart

a

singular

impression

of

medievalism:

through

the

oak

beams

which

support

the

galleries

you

see

black-and-white

half-timbered

houses

on

the

opposite

side

of

the

street,

with

another

'

Row'

cut

through

their

first

floors,

on

whose

balconies

people

are

leaning

and

talking

and

regarding

the

flow

of

life.

The

main

streets

of

Chester

give

you

the

impression

that

a

huge

galleon

has

come

to

anchor

there

with

easy,

leisurely

passengers

leaning

on

the

deck

rails.

This

peculiar

feature

of

Chester

has

worried

the

antiquaries

more

than

anything.

Theories

to

explain

how

and

why

these

peculiar

streets

grew

up

are

numerous

and

none

of

them

definite.

'Who

knows

why

they

are

built?'

said

a

local

antiquary.

'One

theory

is

that

the

ruins

of

the

Roman

buildings

inspired

the

architects

of

later

times.

Another

theory

is

that

the

arcades

were

formed

during

the

Middle

Ages

to

provide

street

defence

against

Welsh

raiders;

a

third

theory

explains

them

on

the

ground

that

traders

erected

their

buildings

on

the

ruins

of

the

Roman

Castrum,

the

most

valuable

ground,

naturally,

in

the

town,

and,

as

other

traders

were

attracted

to

the

same

profitable

site,

a

further

row

of

buildings

rose

up

on

the

ruins

behind

the

first,

from

which,

of

course,

it

is

but

a

step

to

a

covered

arcade

running

the

length

of

the

street.

But

no

one

can

say

with

certainty

how

they

evolved.

'The

Rows'

are

one

of

the

architectural

mysteries

of

England.

Chester

is

as

'medieval'

as

Clovelly

is

'quaint

'.

There

is

no

getting

away

from

it.

At

night

a

walk

through

'the

Rows'

is

eerie.

These

long

tunnels

are

almost

pitch

dark.

When

the

shops

are

closed

they

are

deserted,

for

the

Cestrians

then

take

to

the

normal

roadway,

and

you

can

walk

on

and

on

along

this

ancient

highway,

through

colonnades

upheld

by

vast

oak

beams,

half-expecing

to

hear

the

scuffle

of

hired

assassins

and

the

gasp

of

a

man

with

a

dagger

in

his

neck.

I

have

yet

to

meet

a

more

dramatic

street.

Chester

is

so

accustomed

to

ancient

things

that

no

one

considered

it

strange

to

drink

coffee

in

a

twelfth-century

crypt.

There

is

a

beautiful

vaulted

crypt

which

has

been

converted

into

a

restaurant!

(still

thriving

today,

in

Eastgate

Street.

Ed)

I

went

there

and

sat

utterly

crushed

by

my

surroundings.

I

looked

round

for

the

monks,

but

saw

only

young

men

and

women,

taking,

so

it

seemed,

sacrilegious

sips

of

tea

and

eating

cream

cakes. Chester

is

so

accustomed

to

ancient

things

that

no

one

considered

it

strange

to

drink

coffee

in

a

twelfth-century

crypt.

There

is

a

beautiful

vaulted

crypt

which

has

been

converted

into

a

restaurant!

(still

thriving

today,

in

Eastgate

Street.

Ed)

I

went

there

and

sat

utterly

crushed

by

my

surroundings.

I

looked

round

for

the

monks,

but

saw

only

young

men

and

women,

taking,

so

it

seemed,

sacrilegious

sips

of

tea

and

eating

cream

cakes.

One

of

the

happiest

memories

of

my

search

will

be

the

recollection

of

the

many,

times

I

have

hung

out

of

hotel

and

inn

windows

before

going

to

bed

listening

to

the

night

sounds

of

towns

and

cities

and

villages.

I

must

write

a

story

about

them

some

day.

At

night,

when

the

tramcars

have

stopped

running

and

the

crowds

have

gone

home,

and

the

last

American

has

drunk

the

last

'highball'

in

the

smokeroom,

ancient

cities

like

Chester

come

most

vividly

to

life.

So

you

must

leave

me

in

Chester,

under

a

big

round

moon,

leaning

out

in

the

soft

coolness

of

the

night,

watching

the

Valeria

Victrix

stack

spears

in

the

main

street,

and

stand

back

waiting

for

orders

to

found

one

of

the

oldest

cities

in

England.

And

it

was

on

the

'Holy

Dee',

the

broad,

slow

river

that

winds

itself

round

Chester,

that

King

Edgar

in

973

gave

away

his

character

to

posterity

by

being

rowed

in

his

barge

by

tributary

princes,

And

it

was

in

Chester...

I

could

go

on

through

history

picking

out

little

pictures

of

Chester;

but

it

is

so

late,

and

the

moon

is

riding

high

above

this

silent

city,

where

old

houses

dream

across

old

streets

with

their

roots

among

the

little

red

tiles

of

Rome.

* Over

a

century

before

these

words

were

written-

in October

1811,

to

be

exact-

the Chester

Courant portrayed

a

rather

different

impression

of

the

younger

citzens

who

spent

their

leisure

hours

on

the

Rows:

"The

gangs

of

blackguards

which,

during

the

Winter

season,

infest

the

Rows

of

this

city,

have

commenced

their

nocturnal

outrages. The

south

Row

of

Eastgate

Street

is

the

general

rendevous,

where

they

parade

or

sit

in

groups,

interrupting

the

passage,

or

insulting

everyone

that

passes,

particularly

females,

who

are

perpetually

annoyed

by

their

rude

insults".

Some extracts from the Chester chapter of the 1935 (6th) edition of Dora Benson's British Holidays in North Wales: Some extracts from the Chester chapter of the 1935 (6th) edition of Dora Benson's British Holidays in North Wales:

"The unique characteristics which baffle the descriptive writer, and even the artist, are the most powerful reasons for inducing the visitor to spend a few days in Chester. It is a city where evidences of its antiquity meet the eye on every side. The fine circuit of its Roman Walls, its beautiful cathedral and monastic buildings, its main streets with their half-timbered medieval houses and unique Rows, the old bridge across the lovely river Dee- all these combine to endear it to the student of English architecture and the lover of the picturesque. "The unique characteristics which baffle the descriptive writer, and even the artist, are the most powerful reasons for inducing the visitor to spend a few days in Chester. It is a city where evidences of its antiquity meet the eye on every side. The fine circuit of its Roman Walls, its beautiful cathedral and monastic buildings, its main streets with their half-timbered medieval houses and unique Rows, the old bridge across the lovely river Dee- all these combine to endear it to the student of English architecture and the lover of the picturesque.

In addition to these signs of a long history, are the remains of the Roman fortress of Deva. There is no street, hardly a stone, in this wonderful old city that does not stir the imagination and give memory a thrill.

The most recent discovery of importance is a Roman Legionary amphitheatre, which, although not yet excavated, is believed by experts to be the largest in the British Isles and among the largest in the world.

For all its old-world charm, Chester is modern with modern attractions, and first and foremost among them are the shops. Even apart from their medieval setting, these merit the admiration of visitors; but only those who have experience of the Rows can appreciate how convenient for shopping is that wonderful survival of the Middle Ages which Chester, alone of all the cities in the world, possesses. There are plenty of good hotels; cafes and restaurants are to be found in all the principal streets; there are central garage facilities for an unlimited number of cars, while the corporation has provided no less than four public parking grounds in central positions. Easy access to all parts of the city and suburbs is afforded by up-to-date motor omnibuses.

As a motoring centre, Chester is worthy of attention even by those who have not a private car. It is, moreover, the Gateway to North Wales. The splendidly organized transport services of the district provide an easy means of reaching places of interest, and special tours to the most famous beauty-spots are run very frequently throughout the season.

The walls, which completely encircle the city, are built upon foundations which, in many parts, are undoubtedly Roman; and although the superstructure, in course of time, has been to a large extent renewed, it is nevertheless of great age. The four main gates stand, roughly, at the four points of the compass, and there is also a smaller gate called the Newgate or Peppergate (16th-century) on the south-east. An additional and large Newgate is now under construction to provide for modern traffic requirements.

A continuous promenade of nearly two miles, with delightful views of mountain and river and green meadow, runs along the top of the walls for the complete circuit, and affords a unique experience. A continuous promenade of nearly two miles, with delightful views of mountain and river and green meadow, runs along the top of the walls for the complete circuit, and affords a unique experience.

The medieval appearance of the Chester streets is due to the large number of fine half-timbered houses, and to the Rows. These Rows are a remarkable feature of the City's architecture and are unique. Their special characteristic is the double row of shops, one at street level and the other at first floor level, while the covered footway of the Rows proper provides a continuous thoroughfare for pedestrians on the upper level. The footway of the Rows is in addition to the ordinary footway at street level and is connected thereto by frequent flights of steps.

Right: "Discover, Enjoy, Chester": a German cigarette advertisment

The Rows do not look directly down to the street, but have a series of stalls or balconies between the footway and that of the street, which provides a convenient space for the shopkeeper to display his wares. The origin of the Rows is lost in obscurity, but there can be no question about their suitability as a fashionable promenade. Ladies especially will appreciate, when shopping, the shelter they afford in all weathers.

Probably no other city enjoys such a beautiful river frontage. The most beautiful part of all extends from the Old Dee Bridge eastwards as far as Grosvenor Park, and is known as The Groves. Facing south, it enjoys the maximum of sunshine, and on many a winter's day its temperature is almost sultry. In summer the multitude of boats on the river add to the gaiety of the scene. Boating on the Dee is one of the happiest experiences which Chester has to offer.

The visitor seeking a little relaxation will find a good entertainment at the Royalty Theatre (City Road- Stage plays and Varieties); the Gaumont Palace Super Cinema, Brook Street; the Music Hall Cinema, Northgate Street; the Majestic Cinema, Brook Street; and the Park Cinema, Saltney. New super cinemas under construction: Odeon, Market Square; A.B.C., Foregate Street and also News Cinema, Foregate Street.

Of all of the above 'places of relaxation' of seventy years ago, only the Odeon in Market Square survived- until it was disgracefully closed down in 2007 (and remains so in 2014)...

In

1939,

in

his Life

of

Dickens, Graham

Laud wrote: In

1939,

in

his Life

of

Dickens, Graham

Laud wrote:

"Chester

is

a

glorious

ancient

city

with

a

rare

elegance

in

its

beautifully

preserved

old

buildings.

A

sense

that

all

England's

history

is

encapsulated

here

in

its

broad,

cobbled,

enchanting

streets

and

from

its

2000

year

old

walls

to

the

awesome

cathedral.

Yet

it

is

surprisingly

young

and

lively.

A

living

city

with

a

zing

in

the

air,

yet

mature

and

relaxed,

a

city

that

knows

itself

to

be

happy

in

its

skin.

This

is

the

city

I

grew

up

in

and

loved".

Published

in

1958, T.

H.

White's great

novel The

Once

and

Future

King is

a

wonderfully

witty

and

moving

re-telling

of

the

Arthurian

legend.

It

contains

some

evocative

descriptions

of

life

in

medieval

towns,

including

this

passage

where

the

King

and

his

party

arrive

at Carlion-

(the

Saxon

name

for

Chester

was Caerlion and

our

Welsh-speaking

neighbours

to

this

day

refer

to

the

city

as Caer)-

for

a

wedding: Published

in

1958, T.

H.

White's great

novel The

Once

and

Future

King is

a

wonderfully

witty

and

moving

re-telling

of

the

Arthurian

legend.

It

contains

some

evocative

descriptions

of

life

in

medieval

towns,

including

this

passage

where

the

King

and

his

party

arrive

at Carlion-

(the

Saxon

name

for

Chester

was Caerlion and

our

Welsh-speaking

neighbours

to

this

day

refer

to

the

city

as Caer)-

for

a

wedding:

"The

metropolitan

glories

of

Carlion

were

enough

to

take

their

breaths

away.

Here,

round

the

King's

castle,

there

were

streets-

not

just

one

street-

and

castles

of

dependent

barons,

and

monasteries

and

chapels,

churches,

cathedrals,

markets,

merchant's

houses.

There

were

hundreds

of

people

in

the

streets,

all

dressed

in

blue

or

red

or

green

or

any

bright

colour,

with

shopping

baskets

over

their

arms,

or

driving

hissing

geese

before

them,

or

hurrying

hither

and

thither

in

the

livery

of

some

great

lord.

There

were

bells

ringing,

clocks

smiting

in

belfries,

standards

floating-

until

the

whole

air

above

them

seemed

to

be

alive.

There

were

dogs

and

donkeys

and

palfries

and

farm

wagons-

whose

wheels

creaked

like

the

Day

of

Judgement-

and

booths

which

sold

gilt

gingerbread,

and

shops

where

the

finest

bits

of

of

armour

in

the

very

latest

fashions

were

displayed.

There

were

silk

merchants

and

jewellers.

The

shops

had

painted

trade

signs

hung

over

them,

like

the

inn

signs

which

we

have

today.

There

were

servitors

carousing

outside

wine

shops,

and

old

ladies

haggling

over

eggs,

and

itinerant

cads

carrying

cages

of

hawks

for

sale,

and

portly

aldermen

with

gold

chains,

and

brown

ploughmen

with

hardly

any

clothes

on

except

a

few

bits

of

leather,

and

leashes

of

greyhounds,

and

strange

eastern

men

selling

parrots,

and

pretty

ladies

mincing

along

in

high

dunce's

caps

with

veils

floating

from

the

top

of

them,

and

perhaps

a

page

in

front

of

the

lady,

carrying

a

prayer

book,

if

she

was

going

to

church.

Carlion

was

a walled town,

so

that

this

excitement

was

surrounded

by

a

battlement

which

seemed

to

go

on

for

ever

and

ever.

The

wall

had

towers

every

two

hundred

yards,

and

four

great

gates

as

well.

When

you

were

approaching

the

town

from

across

the

plain,

you

could

see

the

castle

keeps

and

church

spires

springing

out

of

the

wall

in

a

clump-

like

flowers

growing

in

a

pot".

* Robert

Stoker, in

his

book The

Legacy

of

Arthur's

Chester (1963),

pointed

out

that

there

were

actually two cities

bearing

the

name

Caerleon,

and,

after

the

departure

of

the

Legions,

it

was

here,

Caerleon-upon-Dee

that

became

the

ecclesiastical

and

civil

capital

of

the

Kings

of

Britain,

Capital

of

Wales,

GHQ

of

the

centuries-long

campaigns

against

the

Saxons

and

the

city

of

the

coronation,

in

the

early

seventh

century,

of

a

not-so-legendary King

Arthur- not Caerleon-on-Usk

(Roman Isca)

in

South

Wales.

The

confusion

seemingly

lay

with

Arthur's

medieval

chronicler, Geoffrey

of

Monmouth,

whose

patron,

Robert

of

Gloucester,

was

Lord

of

the

Monmouth

Marches,

where

Caerleon-on-Usk

is

situated.

It

seems

that

Geoffrey,

doubtess

partly

in

order

to

please

his

Lord,

attributed

all

references

dealing

with

'Caerleon-ar-Dour'

(Chester)

to

'Caerleon'

without

qualifying

which

one

the

old

chronicles

were

referring

to.

Consequently,

Stoker

claims,

historians

have

ever

since

been

crediting,

for

example,

Isca

with

having

an

archbishop

since

AD180

because

a

local

boy

in

Monmouth

had

said

so

nine

hundred

years

later...

Whatever

the

case,

think

of

the

still-magnificent

old

fortress

when

you

go here to

read

Geoffrey's

description

of

the

coronation

of

King

Arthur).

"I

was

taken

by

your

city

walls,

but

found

Chester

a

city

where

it

was

easier

to

buy

a

crystal

or

a

packet

of

pot-pourri

than

a

pint

of

milk..." "I

was

taken

by

your

city

walls,

but

found

Chester

a

city

where

it

was

easier

to

buy

a

crystal

or

a

packet

of

pot-pourri

than

a

pint

of

milk..."

Graham

Norton: BBC

Radio

4's

'Just

a

Minute',

recorded

at

the

Gateway

Theatre,

Chester,

February

7th

2000 Graham

Norton: BBC

Radio

4's

'Just

a

Minute',

recorded

at

the

Gateway

Theatre,

Chester,

February

7th

2000

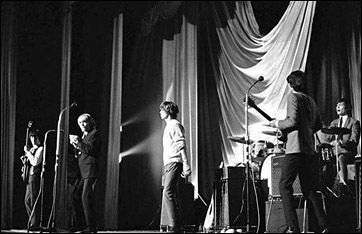

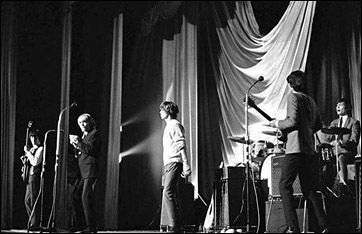

It's difficult to imagine now, but there was a time when major pop groups regularly performed in Chester. The Rolling Stones, for example, played at the Royalty Theatre in April 1964 and at the ABC Cinema along with Inez & Charlie Foxx in September of the same year. In October 1965, they played the ABC again, accompanied by the Moody Blues and the Spencer Davis Group. It's difficult to imagine now, but there was a time when major pop groups regularly performed in Chester. The Rolling Stones, for example, played at the Royalty Theatre in April 1964 and at the ABC Cinema along with Inez & Charlie Foxx in September of the same year. In October 1965, they played the ABC again, accompanied by the Moody Blues and the Spencer Davis Group.

Mick Jagger recalled the surreal end to the September 1964 gig. The band had to escape along the rooftops after the show because the venue was surrounded by screaming teenage fans. “I remember we had a lady pianist with us also, who was one of the opening acts, I forgot her name and she was a concert pianist and it was quite funny.”

Keith Richards recalled the same Chester gig: “One time in Chester, we have the Chief Constable of Cheshire with us in full regalia with the ribbons and the medals and the swagger stick. Show’s finished earlier than he expects. The whole theatre is surrounded. Mayhem. Maniac teenage girls, bless their hearts.

"Right," he says. "The only way out, up the stairs, over the rooftops, I know the way!". Suddenly you’re in his hands. So we get up on the Chester rooftops, and it’s raining. The first thing that happens is the Chief Constable almost slides off the roof. A couple of his bobbies managed to hold him up. We’re standing in the middle of this rooftop saying: "I’m not too familiar with this area, where do we go?"

“He pulls himself together, and in a shambolic sort of way, they manage to get us down through a skylight and out of a laundry chute, or something. That was what happened every day, and you took it as normal. Everything was a Goon Show.”

Keith repeated the story in his autobiography: " I remember once in Chester, after a show that had ended in a riot, following the Chief Constable of Chester Police over the rooftops of Chester city as in some weird Walt Disney film, with the rest of the band behind me and him in full uniform, with a constable at his side. And then he loses his fucking way, and we are perched on the top of Chester city while his great " Escape From Colditz plan diintegrates..."

John Lennon was a frequent visitor to Chester. His sister, Julia Baird, recalled, "During childhood, John and I used to spend a lot of time in Chester. We also used to come to Chester on the train from Liverpool as we always knew that Chester was the best place for clothes shopping. We used to go for lunch at Brown's and walk down by the river. Chester has always been in the family. We are the classic family that moved from Wales to Chester to Liverpool. John was very fond of Chester. We always thought Chester was the place to be, not Liverpool." John and Julia's grandmother, Annie Jane Millward, was born at the Bear and Billet Inn in Lower Bridge Street in 1873 and lived there until she was in her 20s. According to Julia, who was a longtime former Chester resident, "Our great-grandfather (John Denbry Millward) and great-grandmother (Mary Elizabeth Millward nee Morris) lived there. Our great-grandfather was the clerk to the Earl of Shrewsbury, because of that he had the freedom to the city of Chester". John Lennon was a frequent visitor to Chester. His sister, Julia Baird, recalled, "During childhood, John and I used to spend a lot of time in Chester. We also used to come to Chester on the train from Liverpool as we always knew that Chester was the best place for clothes shopping. We used to go for lunch at Brown's and walk down by the river. Chester has always been in the family. We are the classic family that moved from Wales to Chester to Liverpool. John was very fond of Chester. We always thought Chester was the place to be, not Liverpool." John and Julia's grandmother, Annie Jane Millward, was born at the Bear and Billet Inn in Lower Bridge Street in 1873 and lived there until she was in her 20s. According to Julia, who was a longtime former Chester resident, "Our great-grandfather (John Denbry Millward) and great-grandmother (Mary Elizabeth Millward nee Morris) lived there. Our great-grandfather was the clerk to the Earl of Shrewsbury, because of that he had the freedom to the city of Chester".

Annie married George Ernest Stanley, had seven children (the first two died in infancy) - one of whom was John's mother Julia. She died in 1941.

John later returned to Chester- as a Beatle- and the band played here several times at the Riverpark Ballroom on Union Street and the Royalty Theatre in City Road. Neither of these venues exist today- bank offices stand on the site of the Riverpark and a cheap hotel on that of the poor old Royalty.

In

March

2001,

national

UK

newspaper The Independent published

a

free

supplement

entitled "Best

of

Chester:

the

Top

50

Places

to

go

in

Chester",

penned

by 'local

girl' Lucy

Gilmore. In

March

2001,

national

UK

newspaper The Independent published

a

free

supplement

entitled "Best

of

Chester:

the

Top

50

Places

to

go

in

Chester",

penned

by 'local

girl' Lucy

Gilmore.

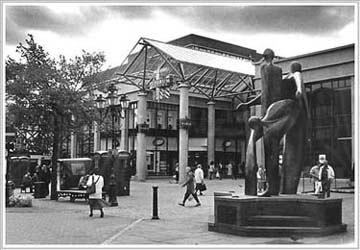

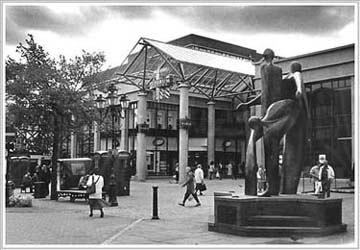

Ms

Gilmore

succeeded

in

producing

a

minor

stink

within

the

city's

tourism

and

publicity

departments

as

a

result

of

her

reference

to

the

covered

market

as, "Originally

atmospheric,

the

entrance

is

now

through

a

tacky

shopping

centre".

This

'tacky

shopping

centre'

actually

being

the

ironically-entitled Forum (illustrated

left-

swathes

of

unique

Roman and

later

remains

were

bulldozed

during

its

construction)-

and

this

despite

its

being

only

recently

tarted-up

courtesy

of

the

Scottish

Widows

insurance

company.

The Forum's

high

point

(and

undoubted

source

of

greatest

public

ridicule)

was

surely

achieved

when,

despite

a

public

outcry,

a

branch

of McDonald's was

opened

there (on

the

far

right

hand

side

of

our

photograph)-

immediately

next

to

the

splendid

Victorian Town

Hall and

facing

the

west

front

of

the

great

medieval Cathedral...

Subsequent to the article's publication, correspondents

to

the

local

press

seemed

to

be in agreement

with

Ms

Gilmore; "Yes,

the

Forum

is

very

tacky!", "I

can't

think

of

a

better

description

of

it",

etc.

(To

see

if

you

agree

with

them,

take

a

look

at

our

feature, When

bad

things

happen

to

good

cities:

the

changing

face

of

the Chester

Market

Hall )

The

above

aside, The

Best

of

Chester contained

further

howlers-

albeit

no

more

than

many

other

'visitor's

guides'

to

our

fair

city.

The

above

referred

to

Market

Hall

was

said

to

feature

"strapping

stallholders

singing

Jerusalem

as

you

sample

ripe

Stilton

Vintage".

We're

told

that

he

Emperor

Hadrian

wanted

fortress Deva (the

city

of

Chester

as

such

not

existing

for

hundreds

more

years)

"to

reflect

the

glory

of

Rome"

and

that

the

ancient Boot

Inn in

Eastgate

Row

"has

a

skittle

alley

at

the

entrance"... We wish it still did- it's been gone for years. But it's a nice pub- with possibly the best value pint in town- nontheless...

The

exhibitions

said

to

be

held

in

the

Summer

in

the Water

Tower and Phoenix

Tower have

not

been

seen

for

several

years,

the

city

council

having closed these

most attractive and interesting

places

in

order

to

save

a

few

pounds-

and

the

excellent Toy

Museum in

Lower

Bridge

Street

was

praised,

despite

its

having being

forced

into

closure

due

to

falling

visitor

numbers

and

rising

city

centre

rent

and

rates.

It

was

ironic

indeed

to

see

the

city's

main

commercial

competitor

and

arch-rival,

the

newly-developed Cheshire

Oaks

Designer

Outlet

Village ("free

parking!")

being

listed

as number

5 of

the

"50

best

places

to

go

in

Chester"!

(We

later

heard

a rumour that Cheshire

Oaks themselves

were

not

too

pleased

about

being

so

described!)

Our

favourite,

however,

was

back

in

the Best

of

Chester's introduction,

where

we

learned

that

"Cestrians,

as

the

inhabitants

of

Chester

are

known,

have

been

welcoming

visitors

for

more

than

2,000

years-

the

Roman

invasion,

the

Norman

invasion,

the

Civil

War..."

To

apply

the

term

'welcoming'

to

those

citizens

who

were

slaughtered,

enslaved,

starved

or

made

homeless

during

centuries

of

military

conflict

and

bloody

siege

was,

we

thought,

even

for

journalism

of

this

standard,

stretching

it

a

bit...

One Mick Brown of the Daily Telegraph rolled into Chester and penned a deeply flawed and rather depressing article about the state of the city's trade (and comparing it unfavourably with Totnes in Devon), which was published on Saturday 13th June 2009: Financial Crisis: High Noon on the High Street. One Mick Brown of the Daily Telegraph rolled into Chester and penned a deeply flawed and rather depressing article about the state of the city's trade (and comparing it unfavourably with Totnes in Devon), which was published on Saturday 13th June 2009: Financial Crisis: High Noon on the High Street.

As may be seen here, a photograph of Eastgate Street that headed this dodgy piece of pseudo-journalism was remarkable in that there is not a single soul to be seen- somebody must have had to get up very early in the morning to get that, obviously in a malicious attempt to give the false impression that Chester has become some sort of commercial ghost town.

We don't know much about the Telegraph's usual way of doing things but this struck us as pretty shabby, gutter press stuff.

Many generations of students have come to Chester to study- and much else! Here are two hilarious- and previously unpublished- true stories by Simon Catterall: Youthful memories of Chester (1974) and Naked Around the Walls! (1984) Many generations of students have come to Chester to study- and much else! Here are two hilarious- and previously unpublished- true stories by Simon Catterall: Youthful memories of Chester (1974) and Naked Around the Walls! (1984)

Written by journalist Tom Dyckhoff, this article, which appeared in The Guardian, Saturday 6th December 2008, contains some interesting impressions of the city as seen with a distincly middle-class slant- and also some telling comments from locals-

Let's move to Chester. Written by journalist Tom Dyckhoff, this article, which appeared in The Guardian, Saturday 6th December 2008, contains some interesting impressions of the city as seen with a distincly middle-class slant- and also some telling comments from locals-

Let's move to Chester.

This satirical little poem, penned by distinguished Chester author and historian Gordon Emery, appeared in the local press in October 2009: This satirical little poem, penned by distinguished Chester author and historian Gordon Emery, appeared in the local press in October 2009:

We voted in the Tories to help mend the wall

But soon a large section began to fall.

With sycamore trees and empty towers

At least we had some ragwort flowers.

The glass slug gone, we wept for joy

Till the Tories bought a new glass toy

Just 20 million - we won’t pay rent

Are the lovely glass walls all that is bent?

Cinema’s gone, theatre too

Nothing for the many, a lot for the few

Chester History & Heritage soon to be shut

Just to pay for council glut.

The council offices meant for the slug

Are now going into a giant glass plug

But please don’t worry, please don’t mope

We’re going to be a City of Culture

- some hope! |

And this very pertinent little piece, responding to the recent erection of some very regrettable buildings- and ludicrous grand plans for more of the same- in our fair city, was recently posted on the (sadly now defunct) Chester@Large City Forum: And this very pertinent little piece, responding to the recent erection of some very regrettable buildings- and ludicrous grand plans for more of the same- in our fair city, was recently posted on the (sadly now defunct) Chester@Large City Forum:

"It appears that many within the planning department of Chester City Council are maybe under the delusion that they are building a new town and, consequently, have attempted to fulfil the following criteria in keeping with new town development,

1) City Council planners must pass an IQ test in order to ensure that they achieve a score no greater than 70. 1) City Council planners must pass an IQ test in order to ensure that they achieve a score no greater than 70.

2) Building must be sporadic with no plan whatsoever.

3) Buildings have to look as ugly as possible. Attractive, historic, and characterful buildings will be demolished to make way for buildings which are in keeping with the vision set forth by Chester City planners.

4) If there exists a free space in the city, build on it.

5) Ignore all and any Roman and historic remains because that's in the past and doesn't count. Historical remains will be counted as "free space".

6) CC planners not accompanied by a guide dog will not be permitted to work within Chester.

An old Welsh proverb, said of getting something done early, was "before the dogs of Chester begin to bark". An old Welsh proverb, said of getting something done early, was "before the dogs of Chester begin to bark".

Still in Wales, we conclude our collection of quotes from Chester's visitors through the ages with this old nursery song, popular for generations with Welsh children. It was recorded by Owen M Edwards in his Hwiangerddi (Nursery Rhymes) in 1911: Still in Wales, we conclude our collection of quotes from Chester's visitors through the ages with this old nursery song, popular for generations with Welsh children. It was recorded by Owen M Edwards in his Hwiangerddi (Nursery Rhymes) in 1911:

Gyrru, gyrru, gyrru i Gaer,

I briodi merch y Maer;

Gyrru, gyrru, gyrru i adre,

Wedi priodi ers diwrnodie.

"Ride and ride and ride to Chester,

There to wed the Mayor's daughter;

Ride, ride home and ride heigh-ho,

Having wedded days ago". |

|

I

noticed

a

band

of

breathless

Americans

standing

on

the

other

side,

utterly

vanquished.

I

decided

to

try

no

conclusions

with

the

Wall

of

Chester

and

passed

on

in

a

superior

way,

mentally

deciding

to

have

a

wish-

for

I

can

never

resist

these

challenges

of

Fate-

some

morning

when

I

could

come

fresh

and

vigorous

to

the

steps.

That,

however,

I

learn

is

not

playing

the

game;

you

must

walk

the

wall

first

and

then

'run

up

and

down

and

up

again',

a

feat

which

I

shall

leave

to

the

natives-

and

to

the

Legions!

I

noticed

a

band

of

breathless

Americans

standing

on

the

other

side,

utterly

vanquished.

I

decided

to

try

no

conclusions

with

the

Wall

of

Chester

and

passed

on

in

a

superior

way,

mentally

deciding

to

have

a

wish-

for

I

can

never

resist

these

challenges

of

Fate-

some

morning

when

I

could

come

fresh

and

vigorous

to

the

steps.

That,

however,

I

learn

is

not

playing

the

game;

you

must

walk

the

wall

first

and

then

'run

up

and

down

and

up

again',

a

feat

which

I

shall

leave

to

the

natives-

and

to

the

Legions!  Chester

is

so

accustomed

to

ancient

things

that

no

one

considered

it

strange

to

drink

coffee

in

a

twelfth-century

crypt.

There

is

a

beautiful

vaulted

crypt

which

has

been

converted

into

a

restaurant!

(still

thriving

today,

in

Eastgate

Street.

Ed)

I

went

there

and

sat

utterly

crushed

by

my

surroundings.

I

looked

round

for

the

monks,

but

saw

only

young

men

and

women,

taking,

so

it

seemed,

sacrilegious

sips

of

tea

and

eating

cream

cakes.

Chester

is

so

accustomed

to

ancient

things

that

no

one

considered

it

strange

to

drink

coffee

in

a

twelfth-century

crypt.

There

is

a

beautiful

vaulted

crypt

which

has

been

converted

into

a

restaurant!

(still

thriving

today,

in

Eastgate

Street.

Ed)

I

went

there

and

sat

utterly

crushed

by

my

surroundings.

I

looked

round

for

the

monks,

but

saw

only

young

men

and

women,

taking,

so

it

seemed,

sacrilegious

sips

of

tea

and

eating

cream

cakes. "The unique characteristics which baffle the descriptive writer, and even the artist, are the most powerful reasons for inducing the visitor to spend a few days in Chester. It is a city where evidences of its antiquity meet the eye on every side. The fine circuit of its Roman Walls, its beautiful cathedral and monastic buildings, its main streets with their half-timbered medieval houses and unique Rows, the old

"The unique characteristics which baffle the descriptive writer, and even the artist, are the most powerful reasons for inducing the visitor to spend a few days in Chester. It is a city where evidences of its antiquity meet the eye on every side. The fine circuit of its Roman Walls, its beautiful cathedral and monastic buildings, its main streets with their half-timbered medieval houses and unique Rows, the old  A continuous promenade of nearly two miles, with delightful views of mountain and river and green meadow, runs along the top of the walls for the complete circuit, and affords a unique experience.

A continuous promenade of nearly two miles, with delightful views of mountain and river and green meadow, runs along the top of the walls for the complete circuit, and affords a unique experience.

1) City Council planners must pass an IQ test in order to ensure that they achieve a score no greater than 70.

1) City Council planners must pass an IQ test in order to ensure that they achieve a score no greater than 70.