"In whatever point of view these old ramparts are considered, they possess an imposing interest and confer incalculable benefits. To the invalid, the sedenatary student, or the man of business, occupied during the day in his shop or counting house; to the habitually indolent, who require excitement to necessary exercise, to all these, the promenade on Chester walls has most inviting attractions, where they may breath all the salubrous winds of heaven in a morning or an evening walk. "In whatever point of view these old ramparts are considered, they possess an imposing interest and confer incalculable benefits. To the invalid, the sedenatary student, or the man of business, occupied during the day in his shop or counting house; to the habitually indolent, who require excitement to necessary exercise, to all these, the promenade on Chester walls has most inviting attractions, where they may breath all the salubrous winds of heaven in a morning or an evening walk.

Here the enthusiastic antiquarian, who would climb mountains, ford rivers, explore the bowels of the earth, and, regardless of toil, and the claims of nature, exhaust his strength in the search for a piece of rusty cankered brass, or a scrap of Roman earthenware, can scarcely advance a dozen paces, but the pavement on which he treads, or some contiguous object, forces upon his observation the reliques of times of earliest date.

Nor can the philosophic moralist encompass our venerable walls without having his mind, comparing the splendid and gigantic works of antiquity with their present condition, strongly impressed with the mutations produced by the lapse of ages, and the perishing nature of all mundane greatness".

Joseph Hemingway: Panorama of the City of Chester 1836

n

1069,

Chester

was

the

last

city

in

England to

fall

to

William

the

Conqueror's

army,

a

full

three

years

after

the

Battle

of

Hastings. Rumours

had

long

circulated

among

the

Norman

troops

about

the

difficult

roads,

the

position

of

the

city-

surrounded

as

it

was

by

marshes

and

great

forests-

of

its

numerous

inhabitants-

and

of

their

obstinate

courage: "Locorum

asperitatum

et

hostium

terribilem

ferocitatem". n

1069,

Chester

was

the

last

city

in

England to

fall

to

William

the

Conqueror's

army,

a

full

three

years

after

the

Battle

of

Hastings. Rumours

had

long

circulated

among

the

Norman

troops

about

the

difficult

roads,

the

position

of

the

city-

surrounded

as

it

was

by

marshes

and

great

forests-

of

its

numerous

inhabitants-

and

of

their

obstinate

courage: "Locorum

asperitatum

et

hostium

terribilem

ferocitatem".

Many

of

William's

nobles,

worn

out

by

the

bloody

struggles

to

repress

rebellions

in

Yorkshire

and

Northumberland

during

the Harrying

of

the

North,

and

alarmed

at

these

rumours,

demanded

their

discharge.

Some

retreated

to

their

estates

in

Normandy

and

abandoned

the

English

lands

with

which

they

had

already

been

rewarded.

But

the

persuasive

powers

of

Duke

William

prevailed.

With

the

conquest

of

Chester,

he

told

them,

their

labours

would

be

at

an

end

and

rest

and

great

rewards

would

follow.

As

it

turned

out,

as

the

Norman

army

drew

near,

the

city-

whose

citizens

had

doubtless

heard

equally

terrifying

rumours

regarding

the

approaching

foe-

surrendered.

How

much

resistance

they

put

up

is

unknown,

but,

seventeen

years after

the

city's

fall,

the Domesday

Book stated

that

before

1066

there

had

been

431

houses,

"plus

56

more

owned

by

the

Bishop"

in

the

city

and

that

it

paid

fourty

five

pounds

"and

one

hundred

and

twenty

martin

skins"

but,

"When

Earl

Hugh

acquired

it,

its

value

was

only

thirty

pounds,

having

been

much

devastated;

there

were

205

houses

less

than

before

1066".

Duke

William

granted

the

Earldom

of

Chester

first

to Walter

de

Gherbaud,

who,

however

soon

returned

to

Normandy,

and

then

to

his

nephew, Hugh

d'Avranches,

know

as Lupus (The

Wolf)

-

"to

hold

to

him

and

his

heirs

as

freely

by

the

sword

as

the

King

holds

the

Crown

of

England".

Ordericus

described

him

thus: Duke

William

granted

the

Earldom

of

Chester

first

to Walter

de

Gherbaud,

who,

however

soon

returned

to

Normandy,

and

then

to

his

nephew, Hugh

d'Avranches,

know

as Lupus (The

Wolf)

-

"to

hold

to

him

and

his

heirs

as

freely

by

the

sword

as

the

King

holds

the

Crown

of

England".

Ordericus

described

him

thus:

"He

was

not

abudantly

liberal,

but

he

was

profusely

prodigal

and

carried

not

so

much

a

family

as

an

army

around

with

him.

He

took

no

account

either

of

receipts

or

disbursements;

he

daily

wasted

his

Estate

and

delighted

more

in

falconers

and

huntsmen

than

in

the

tillers

of

his

land

or

Heaven's

orators,

the

Ministers.

He

was

much

given

to

his

belly,

whereby

in

time

he

grew

so

fat

that

he

could

scarce

crawle.

He

had

many

bastard

sons

and

daughters,

but

they

were

nearly

all

swept

away

by

sundry

misfortunes".

Actually, there is no evidence that Earl Hugh was called by the unpleasant name of Lupus during his lifetime or indeed for long years after his death. It was given to him in later ages on account of his traditional gluttony and rapacity. The Welsh called him Hugh the fat or gross, 'Hu vras', and the Danes 'Hugh Dirgane' which has the same meaning. The earliest instance of the use of the nickname Lupus occurs in an inquisition as late as 1305- "Hugo le Lou

formerly Earl of Chester".

The

Earldom

became

very

powerful

and

virtually

independent

of

the

Crown,

the

Earl

having

his

own

Parliament

consisting

of

eight

of

his

chosen

Barons

and

their

tenants,

and

they

were

in

no

way

bound

by

any

laws

passed

by

the

English

Parliament

with

the

exception

of

treason.

The

Saxon Castle was

rebuilt

and

greatly

enlarged

and

strengthened,

becoming

the caput of

the

Earldom-

as

were

the

city

walls. The

Saxon Castle was

rebuilt

and

greatly

enlarged

and

strengthened,

becoming

the caput of

the

Earldom-

as

were

the

city

walls.

In

1093,

in

the

last

days

of

his

life,

Earl

Hugh

founded

the Benedictine

Abbey

of

St. Werburgh, "To

make

provision

for

his

immortal

soul

and

and

to

compensate

to

some

degree

for

the

sins

which

he

had

committed".

In

time,

the

Abbey

became

extremely

rich

and

powerful,

owning

land

and

property

throughout

Cheshire

and

far

beyond.

The

Earls

of

Chester

gave

the

Abbots

rights

equal

within

their

jurisdiction

to

their

own,

which

were

themselves

equal

to

those

of

the

Crown

elsewhere

in

the

country.

The

medieval

trials

by

fire,

water

and

combat

were

practiced

in

the

Abbot's

courts

and

malefactors

were

executed

by

the

Abbot's

officers.

After

the

Dissolution

in

1540,

the

Abbey

became Chester

Cathedral.

During

the

13th

century

the

city

played

a

major

role

in

Edward

I's

subjugation

of

the

Welsh,

who

had,

from

the

8th

century,

when

the

Mercian

King

Offa

had

built

his

great

dyke

to

keep

out

the

dispossessed

Welsh

of

Gwynedd,

Powys

and

Gwent,

long

proved

a

very

real

threat.

The

wars

of

1277

and

1282

resulted

in

the

death

of

the

powerful

Welsh

Prince

Llewellyn

and

the

final

conquest

of

North

Wales.

Many

of

the

violent

events

of

the

revolt

against

the

English

led

by

Owen

Glendower

between

1400

and

1412

took

place

along

the

border

on

the

banks

of

the

River

Dee

near

Chester

and

in

North

Wales.

Two

and

a

half

centuries

later

Chester's

walls

witnessed

bloody

conflict

for

a

final

time,

Englishman

against

Englishman,

during

the Civil

War,

when

Royalist

Chester

eventually

fell

to

Parliamentary

forces

after

a

bitter

and

lengthy

siege

During

the

late

18th

and

early

19th

centuries,

the

formidable

medieval

entrances

to

the

city,

the Northgate, Eastgate, Watergate and Bridgegate,

being

considered

obstructions

to

traffic

in

the

increasingly

busy

town,

were

removed

and

replaced

with

the

present

elegant

arches-

but

retained

their

ancient

names.

A

smaller

entrance,

the Shipgate,

which

formerly

stood

near

the

Bridgegate,

was

completely

removed

and

now

stands

as

a

decorative

folly

in

Grosvenor

Park and its neighbour, the Horsegate, vanished without trace. A

smaller

entrance,

the Shipgate,

which

formerly

stood

near

the

Bridgegate,

was

completely

removed

and

now

stands

as

a

decorative

folly

in

Grosvenor

Park and its neighbour, the Horsegate, vanished without trace.

The

ancient Peppergate,

or Wolfgate,

still

stands in

situ,

but

in

the

1930s,

together

with

the

nearby

Roman Amphitheatre,

narrowly

escaped

destruction

when

the

road

was

diverted

to

allow

traffic

to

use

a

larger

entrance

built

alongside,

appropriately

known

as

the Newgate,

which

now

forms

part

of

the

traffic-choked inner

ring

road.

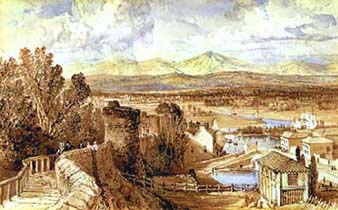

In

1966,

as

part

of

this

new

road

scheme,

the

walls

were

pierced

once

again,

this

latest

entrance

being

called St. Martin's

Gate,

situated

approximately

where

the

artist Thomas

Allom (1804-72)

was

standing

150

years

earlier

when

he

produced

this

romantic

study,

which

shows

a

view

of

the

North

Wall

looking

west

towards

the

then-thriving Port

of

Chester,

beyond

which

rise

the

hills

of

North

Wales.

On

the

right

you

can

see

the

18th

century Telford's

Warehouse on

Tower

Wharf,

today

a

lively

pub

/

restaurant

and

Chester's

foremost

live

music

and

arts

venue.

In

the

foreground

may

be

seen

the Goblin

Tower,

today

more

commonly

known

as Pemberton's

Parlour,

and

beyond

that

may

be

seen

the

curiously-named Bonewaldesthorne's

Tower.

In

1846

the

North

Wales

Railway

was

cut

through

the

walls

between

these

two

towers.

Today,

it

forms

part

of

the

main

line

between

London

and

the

Irish

Ferries

at

Holyhead.

Around

the

time

of

the

18th

century

alterations

to

the

gates,

the

walls,

crumbling

and

full

of

breaches

after

their

long

battering

in

the

Siege

of Chester

during

the

Civil

War

a

century

earlier,

were

extensively

repaired

and

converted

to

provide

a

promenade

along

their

entire

length,

a

remarkable

undertaking

at

a

time

when

the

majority

of

other

British

towns

were

busily

doing

away

with

their

ancient

defences. Around

the

time

of

the

18th

century

alterations

to

the

gates,

the

walls,

crumbling

and

full

of

breaches

after

their

long

battering

in

the

Siege

of Chester

during

the

Civil

War

a

century

earlier,

were

extensively

repaired

and

converted

to

provide

a

promenade

along

their

entire

length,

a

remarkable

undertaking

at

a

time

when

the

majority

of

other

British

towns

were

busily

doing

away

with

their

ancient

defences.

Since

that

time,

many

thousands

of

visitors

have

enjoyed

the

two-mile

walk

around

Chester's

ancient

circuit

of

city

walls.

It

remains

a

fascinating

experience

and

should

be

considered

an

essential

part

of

your

visit

to

the

UK.

So

read

the

accounts

of

generations

of past

visitors

to

Chester- and

see

below

for

details

of

our

informative

and

entertaining

guided

walks

around

the

sights

of

this

most

unique and memorable

of

English

cities.

Chester

Today

Modern

Chester

is

by

no

means

'set

in

amber'

but

is

a

living,

growing

place

facing

the

same

problems

and

pressures

as

most

of

Britain's

other

historic

cities. Many

visitors,

having

admired

the

popular,

nostalgic

paintings

of Louise

Rayner and

read

old traveller's

tales of "Quaint,

sleepy,

crumbling

Chester",

are

surprised

to

encounter

the

rapidly-expanding

industrial,

commercial

and

residential

areas

surrounding

the

town

and

the

too-often

mediocre

and

inappropriate

modern

developments

within

the

city

itself.

Many

are

also

surprised

to

discover

that,

in

a

place

fond

of

referring

to

itself

as

'Roman

City', actual Roman

antiquities

are

somewhat

thin

on

the

ground,

having

been

largely

bulldozed

or

buried

to

make

way

for

shopping

precincts,

council

offices,

courthouses and hotels...

As

a

caring

resident,

this

writer

is

inclined

to

agree

with

them

and

will

be

discussing

some

of

these

blots

as

we

encounter

them

during

the

course

of

our

wanderings. As

a

caring

resident,

this

writer

is

inclined

to

agree

with

them

and

will

be

discussing

some

of

these

blots

as

we

encounter

them

during

the

course

of

our

wanderings.

In

contrast

to

British

cities

such

as

Liverpool

and

Coventry,

Chester

largely

escaped

major

damage

during

the

Second

World

War,

but

the

straightened

economic

conditions

that

followed

nevertheless

produced

years

of

neglect

and

under-maintainance

to

the

historic

core

of

the

city

centre,

resulting

in

levels

of

dereliction

today's

visitors

would

find

difficult

to

believe.

Alongside

the

rise

of

ring

roads,

car

parks

and

precincts,

it

should

be

remembered

that,

during

the

1970s

and

80s,

there

also

took

place

a

programme

of

rescue

and

restoration

on

a

heroic

scale

of

literally

hundreds

of

the

buildings

we

prize

today

and

some

of

these

stories

will

also

be

told.

Transport,

too,

has

long

been

the

subject

of

heated

local

debate.

Some

say

that,

in

the

face

of

competition

from

nearby

out-of-town

'shopping

cities',

business

in

Chester

can

only

prosper

by

welcoming

the

car

driver

into

the

city

centre

(despite

the

resulting

congestion

and

pollution

that

plagued

it

in

the

past),

increasing

the

number

of

parking

places

and

reducing

their

charges-

while

others

say

that

visitors

and

shoppers

respond

far

more

positively

to

the

relaxed

and

unhurried

atmosphere

experienced

when

they

are

no

longer

forced

to

share

the

streets

with

motor

vehicles.

Most

welcome

to

many

citizens

has

been

the

slow-but-steady

increase

in

the

numbers

of

cycleways/footpaths

in

and

around

Chester,

allowing

them

safe,

easy,

car-free

access

to

both

the

city

centre

and

its

wonderful

surrounding

countryside.

Among

these

are

the

recently-completed Riverside Path, the restored

towpath

of

the Shropshire

Union

Canal and

the

magnificent

route

along

the

former Mickle

Trafford-Deeside

Railway-

sadly

currently

threatened

by

a controversial

council

plan

to

construct

a

bus

route

along

it.

Many

mourn

the

dramatic

decline

in

traditional

businesses

in

Chester

city

centre

of

recent

years.

As

a

child,

this

writer

vividly

remembers

the

enthusiasm

of

female

members

of

his

family

at

the

prospect

of

a

shopping

trip

to

Chester,

where

he

would

be

forced

to

endure

a

seemingly-endless

round

of

exotic

shops

from

where

could

be

obtained

all

manner

of

delights

unknown

in

battered,

post-war

Liverpool.

Studying

photographs

of

the

main

shopping

areas

dating

from

even

just

a

few

decades

ago

reveals

grocers,

confectioners,

butchers,

ironmongers,

tailors,

photographers

and

the

like

(and

a

lot

more pubs than

now)

occupy

the

majority

of

the

shops

along

the

ancient Rows.

Today,

the

tables

seem

to

have

been

been

somewhat

turned,

as Liverpool city

centre

seems

to

be

thriving

while

ludicrously-high

levels

of

rent

and

rates

in

Chester

have

ensured

that

virtually

all

of

the

old

family-run

businesses

have

now

gone,

replaced

by

estate

agents,

mobile

phone

shops,

national

chain

stores-

and

especially

by

a

plague

of

coffee

shops,

of

which

an

excessive

number

seem

to

have

opened

of

recent

times. Today,

the

tables

seem

to

have

been

been

somewhat

turned,

as Liverpool city

centre

seems

to

be

thriving

while

ludicrously-high

levels

of

rent

and

rates

in

Chester

have

ensured

that

virtually

all

of

the

old

family-run

businesses

have

now

gone,

replaced

by

estate

agents,

mobile

phone

shops,

national

chain

stores-

and

especially

by

a

plague

of

coffee

shops,

of

which

an

excessive

number

seem

to

have

opened

of

recent

times.

At

the

time

of

writing

for

example-

Summer

2001-

a

smallish

vacant

shop

near

The

Cross

was

available

at

a

rent

of seventy

thousand

pounds per

year

(no

wonder

you

can't

buy

a

bag

of

nails

or

a

packet

of

tea

in

Chester

city

centre!)

while,

at

the

same

time,

two

long-established

art

businesses

and

a

wonderful

toy

museum

were

being

forced

to

close

down.

Similarly,

there

was

a

time

when

most

people

lived

within

and

close

to

the

City

Walls

while

the

more

affluent

removed

themselves

to

the

leafy

suburbs.

Today,

most

of

those

local

folk

who

reside

on

the

large

post-war

estates,

well

out

of

sight

on

the

edge

of

the

city,

would

find

it

impossible

to

be

able

to

afford

the

so-called

'luxury'

apartments

and

town

houses

currently

springing

up

in

numerous

locations

in

the

centre.

Valued facilities continue to disappear from the city centre- hardly a week goes by without news of another traditional pub closing. The vast, and apparently inevitable, Northgate Redevelopment, recent announcements concerning the planned replacement of the award-winning Northgate Arena leisure centre with yet another hotel and the acquisition of our last city centre cinema- the Odeon- by a nightclub company are current sources of great local concern, and the continuing imposition within our historic city of ghastly 1960s-style structures such as the Travelodge illustrated on the right beggars belief... Valued facilities continue to disappear from the city centre- hardly a week goes by without news of another traditional pub closing. The vast, and apparently inevitable, Northgate Redevelopment, recent announcements concerning the planned replacement of the award-winning Northgate Arena leisure centre with yet another hotel and the acquisition of our last city centre cinema- the Odeon- by a nightclub company are current sources of great local concern, and the continuing imposition within our historic city of ghastly 1960s-style structures such as the Travelodge illustrated on the right beggars belief...

Some

may

call

it

'commercial

reality',

others

philistinism and naked

greed-

the

results

are, sadly,

the

much

the

same.

The city is awash with well-funded organisations purporting to represent, speak for, and publicise Chester to the world but precious few of them would appear even remotely competent to do so.

This

ancient

city

of

Chester is changing

rapidly-

many

say

too

rapidly.

What

sort

of

a

place

it

will

become,

and

whether,

having

done

so,

it

will

have

managed

to

retain

some

portion

of

its

uniqueness,

its

attraction

for

residents

and

fascination

for

visitors

from

all

over

the

globe-

or become just another Anytown UK- are

questions

only

time

can

answer. Chester Renaissance, the council sponsored- but nontheless unelected- body charged with dragging the old place kicking and screaming into the 21st century, declares its aim is to "make Chester a must-see city by the year 2015" and The One City Plan- the latest in a long line of such plans- has just (June 2102) been published as its blueprint. That it has been a 'must see city' to millions of visitors for many centuries is something seemingly lost upon these imported 'experts'. What sort of city they manage to turn it into we must wait and see; will the world continue to flock to admire their handiwork- a place of bright new hotels, apartments, 'business quarters' and shopping precincts? We wonder.

So we invite you to enjoy Old Chester while you can!

Check

out

the route

map, search our site in detail with Google or go

straight

to

the start of our walk at the Northgate... |