s we have previously heard, Past Forward, best know for the Jorvik Centre in York have already estimated that a fully-excavated amphitheatre and quality visitor centre could turn the site into "an innovative visitor attraction of regional and national significance" attracting around 180,000 visitors per year. Their findings were published in September 2001 and the following is a summary: s we have previously heard, Past Forward, best know for the Jorvik Centre in York have already estimated that a fully-excavated amphitheatre and quality visitor centre could turn the site into "an innovative visitor attraction of regional and national significance" attracting around 180,000 visitors per year. Their findings were published in September 2001 and the following is a summary:

"Within this report we have come to the following conclusions and make the following recommendations:

1. Chester Amphitheatre has a fascinating story to tell and is one worth telling well.

2. The Amphitheatre site makes an ideal location for the setting out of an exciting and innovative visitor attraction which will be unique both on a regional and national level.

3. Visitor figures, given a £2.1 - £2.8 million exhibition and good marketing, can be expected to be in the region of 185,000 per year.

4. The final cost wll depend on the scale and the degree of technology used. Taking the middle exhibition costs, the sum to develop the exhibition in aspace of 1,400 sq metres is £2.1 - 2.8 million.

5. Option Two, turning Dee House into a visitor centre is the least preferred of all the options, as it reduces income streams to one and is reliant on visitor figures. We propose that Option One is is a feasible low-risk option, with Options Three and Four being the high-risk but potentially very profitable options.

6. A key to success will be to create an innovative, exciting and engaging visitor experience, incorporating a number of multimedia and interactive elements.

7. It will create fifteen full-time equivalent jobs.

8. At the projected attendance levels the attraction can generate a surplus of income over expenditure of £430,297 per year.

8a. The break even number of visitors is 108,953 per annum.

9. We conclude that there is considerable merit in implementing such a proposal.

10. Such a project would take some eighteen months to deliver from the point where the funding is available".

The Options:

Option One

: (Low risk- low cost- short to medium term- medium income generation) Utilise existing Chester Visitor Centre for new visitor attraction. Develop Dee House as commercial cafe / bar / restaurant facilities. Use income generated (ultimately) to buy back court building then demolish Dee House and court and excavate.

Option Two: (High risk- medium cost- short to medium term- low income generation) Use Dee House as visitor attraction.

Option Three: (High risk- high cost- medium to long term- high income generation) Clear whole site, fully excavate, build visitor attraction under arena area. (a world-beating attraction dependent upon acquisition and demolition of court buildings)

Option 3A: Incorporate Dee House too.

Option Four: (High risk- variable/high cost- medium to long term- medium/high income generation depending upon scale) New building on the site to replace or maybe add to Dee House to provide visitor attraction.

• What eventually, became of the Past Forward proposals is unsure, but by twelve years later, Summer 2013, their existence has been entirely forgotten.

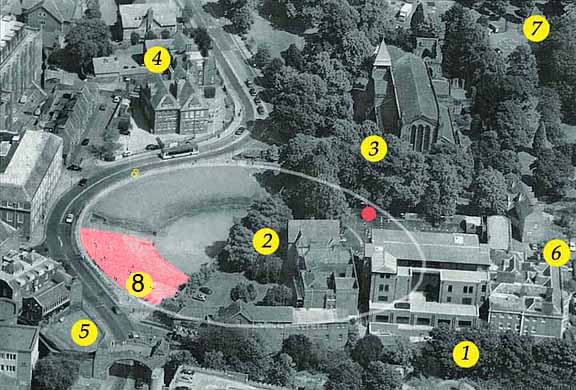

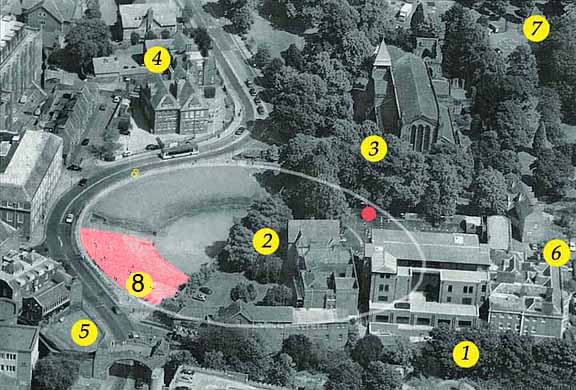

Here we see a fascinating aerial photograph of the Chester amphitheatre as it appeared during the late summer of 2001. Even more clearly than this earlier illustration, it shows how the long term sorry state of the monument has been made so much worse by the (to the minds of many, still hardly creditable) erection of David McLean's courthouse (1) over part of it. Viewed from above, the sheer size and extremely incongruity of the setting of this utilitarian structure, surrounded as it is by the Roman Garden and Newgate (5), the ancient Church of St. John the Baptist (3), the Bishop's Palace (6) and Grosvenor Park (7) seems obvious. Here we see a fascinating aerial photograph of the Chester amphitheatre as it appeared during the late summer of 2001. Even more clearly than this earlier illustration, it shows how the long term sorry state of the monument has been made so much worse by the (to the minds of many, still hardly creditable) erection of David McLean's courthouse (1) over part of it. Viewed from above, the sheer size and extremely incongruity of the setting of this utilitarian structure, surrounded as it is by the Roman Garden and Newgate (5), the ancient Church of St. John the Baptist (3), the Bishop's Palace (6) and Grosvenor Park (7) seems obvious.

Also at (5), to the left of Walter Tapper's Newgate, which opened to traffic in 1938- and obscured by a bush- is the original entrance through the city walls, the Peppergate or Wolfgate. In the small garden you can see in front of the Wolfgate are displayed the excavated remains of the Roman south-east corner tower dating from the earliest days of the stone fortress- around 81-96 AD. At this point, the original Roman South Wall turned west (out of the bottom of the picture) roughly following the line of the righ-hand side of Pepper Street.

As we learned at the start of our exploration of the amphitheatre, during the 1930s, soon after the monument was discovered, the city fathers had intended to drive their new road in a straight line from the Newgate to join up with the straight stretch at the top of the picture, next to the former school that was, until recently the Chester Visitor Centre and the offices of Chester Renaissance. The latter has now been seriously downsized and operates out of a small office in Abbey Square. The ground floor now hosts the excellent St. John's Church Visitor Centre (4).

The (none too accurate) white ellipse superimposed upon the photograph gives some idea of the full scale of the half-buried amphitheatre- and just how much would have to be removed in order to allow for a complete excavation of the monument- notably, of course, Dee House (2), the buildings alongside Souter's Lane (in the foreground)- and, of course, the courthouse itself.

You may just see the lines crudely painted on the court car park (marked with a red dot- and discussed here) to indicate the presence of the buried amphitheatre beneath.

The pink area (8), together with a small area hidden by trees (2), shows the approximate extent of the 'major' excavation project of 2004/5.

Three years later- August 2008- this area had still no been restored and remained an unsightly wasteland of stone chippings (but, in 2010, worse was to come, as we will see....)

The amphitheatre story was featured once again on BBC Radio 4 just before Christmas 2001. In a rather hurried interview- cut short by breaking news from Afghanistan- at the end of the morning Today programme, Henry Owen John from English Heritage and Dr. Lian Smith of the Chester Amphitheatre Trust presented their cases for and against the retention of Dee House.

After giving a brief history of the site and outlining the importance of the monument, Dr Smith said that "We're not talking about a building in its prime- it has wet rot and dry rot. If this was a TV programme and we had a vote on the matter, people would quickly agree with the majority of the people of Chester who say it's a blot on the landscape and it's time that it went".

The perfectly-chinless Henry Owen John, on the other hand, felt that Dee House "was perfectly capable of being brought back into beneficial use to provide an additional level of amenity in terms of understanding the Roman amphitheatre".

Whatever that may mean. Why don't these 'experts' speak plain English?

He did, however, assure listeners that, even with Dee House still beneficially in place, there was "much, much more" that could be done without losing the historic building. "We could, for example, excavate the Western Entrance, make it much more intelligible for the public. It would be possible to research the unexcavated part of the amphitheatre, where we're not just dealing with Dee House, but with 1,600 years of post-Roman history".

A good point. Indeed, the currently-cheerless, newly-landscaped expanse of sand-covered ground lying between the amphitheatre's boundary wall and Dee House could indeed be advantageously excavated right up to the walls of Dee House.

No mention was made of the embarrassing presence of the courthouse during the entire interview- apparently upon the insistence of English Heritage. No mention was made of the embarrassing presence of the courthouse during the entire interview- apparently upon the insistence of English Heritage.

Mr Owen John concluded by assuring us that English Heritage was working with the Chester Amphitheatre Trust and others to produce a "phased approach" to the eventual excavation of the monument.

Back in 1987, however, English Heritage are on record as having come to somewhat different conclusions. During the lengthy Local Inquiry into The Deva Roman Experience, local entepreneur Tony Barbet's bold proposals not only to demolish Dee House and excavate the hidden portion of the amphitheatre, but, more controversially, to reconstruct a portion of the site to appear as it would in Roman times, the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England (ie English Heritage)'s Head of Ancient Monuments, Mrs E J Sharman, came to the following conclusions about Dee House (which was then, remember, in far better condition than it is now):

"While it is in a conservation area, it does not relate closely to other listed buildings in the area and the general quality of the present setting, including its juxtaposition with the half-exposed amphitheatre, is not satisfactory.

The Roman amphitheatre, on the other hand, is a monument of considerably greater historical rarity than Dee House. That part of the structure which has already been excavated is difficult to present and appreciate in its truncated form, and it is displayed in a setting which neither enhances the monument itself nor the quality of the wider conservation area.

Excavations already carried out in the 1960s to display the northern part strongly suggest that the remaining portion of the amphitheatre can be successfully recovered and displayed. The opportunity, therefore, exists to for presenting the whole in a way which would not only secure the consolidation of the monument itself, but very considerably increase the potential for public understanding and enjoyment of it. This opportunity may well not recur since the site is subject to development pressures which, if the Deva scheme does not go ahead, could result in the untimate loss of part of the amphitheatre under other development.

The Commission has considered carefully whether the objectives of the Deva scheme could be met if Dee House were to be retained, but concluded reluctantly that such a compromise would not make sense. Dee House not only straddles a significiant part of the ground which will need to be excavated to display the missing half of the amphitheatre, but with its considerable bulk would destroy the possibility of presenting the amphitheatre as a whole, which is the main purpose of the proposals to which the Commission is prepared to lend its support.

Taken as a whole, the Commission considers that the Deva Centre proposals represent an imaginative and feasable scheme which will provide a positive gain to the community in terms of access to and display of a monument of very considerable public importance. While regretting the historical loss which would be involved in the demolition of Dee House, the Commission is of the opinion that, on balance, the advantages of ther Deva scheme must outweigh this loss. These advantages are, in its view, sufficient to justify overriding the normal presumption in favour of the preservation of the listed building".

Regarding the current condition of Dee House (illustrated right and see interior view below), we have spoken to two individuals- one of them a County Councillor- who have looked around the building since Christmas. They were both horrified by the state of the interior, apparently far worse than they have been led to believe. The entire structure is apparently being held up by immense amounts of scaffolding, rows of which are placed three feet apart on all three stories, each holding up the floor above it. Regarding the current condition of Dee House (illustrated right and see interior view below), we have spoken to two individuals- one of them a County Councillor- who have looked around the building since Christmas. They were both horrified by the state of the interior, apparently far worse than they have been led to believe. The entire structure is apparently being held up by immense amounts of scaffolding, rows of which are placed three feet apart on all three stories, each holding up the floor above it.

And, on February 14th 2001, Alex Woods contributed this remarkable insider's view of the state of the building:

"As you know, when BT took possession of the Dee House site no plans existed and I was one of two people who spent three weeks measuring the site and then preparing plans. Subsequent to this I was involved in the detailed location of every person that worked there. I probably know more of the detail of the interior of the structures on the site than anyone in Chester.

Much of it was rotten then but let's stick to the so-called Georgian bit. The country is littered with Georgian houses but perhaps a good one is significant. Dee House is not a good Georgian house. Detailed examination at ground floor level show at its centre thick irregular walls, forming an equally irregular L-shaped structure which our so-called Georgian house is built on and around. Like everything on the site except the amphitheatre itself it is a hotchpotch of odds and ends and should have been demolished long ago. Chester has precious few, if any, Roman remains which are standing where they were actually built. The amphitheatre could make up for that. Maximum excavation should take place before any other use is even considered".

A week later, Mr C. F. Wright contributed these further thoughts:

"If Dee House were to be brought back into an appropriate use, what must be done? Not just a repair job and a makeover. Whether plushy chambers for lawyers, or yet another restaurant and club. Dee House would have to meet the full range of today's building regulations and health and safety requirements. It would also need fundamental changes in plan to satisfy such uses.

During years of neglect, and after fire damage, dry rot rampaged through the roof and floor timbers; it is still active. Structural walls are collapsing; they are stable at the moment, but only a forest of internal scaffolding keeps Dee House standing. Even the author of the conservation plan could not examine some parts when making their inspection, because of risks to their personal safety.

Any future use will impose much heavier loading on the new floors, walls and foundations than in the past. Keeping Dee House will involve a very substantial rebuild behind the front wall, not just the refurbishment, to the extent that- once through the front door- we shall walk into a building that is not the listed Georgian town house that it once was, whatever its use may be.

The authorities have been very coy about the likely cost of all this- in 1999 a sum of almost two million pounds was mentioned. Over two years later, the building hasn't come down, but how much has the cost of delay gone up? If Dee House is rebuilt, the city council- quite reasonably- will want to keep it going as long as possible to try and get some return on onr money.

That also provides a ready-made excuse for doing very little about excavating the buried more-than-half of our amphitheatre. If it's not excavated within this decade, it could become inaccessible for generations. The plan identifies the source of this risk (p.89, 4.3.3)- "Vulnerability to future development pressures . . . the trend towards use of inner city sites could . . . either damage existing remains or prevent investigation and future public display".

When we remember that in 1995 a city planning committee allowed a commercial developer to overbuild a Roman monument of international importance the mind recoils at the thought of what its successors might be capable of in a few years time".

What indeed?

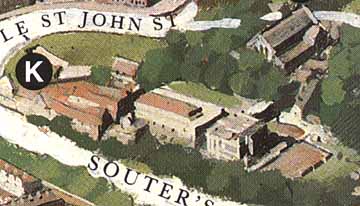

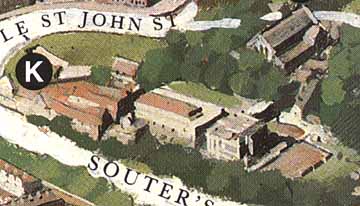

Here's a curiousity. While perusing a recently-acquired copy of Chester, a guidebook published by Pevensey Heritage Guides (a branch of Reader's Digest), we were attracted by a large, painted 'aerial view' of our fine city- a detail of which is reproduced here- but were surprised by the appearance of a large building shown standing between the amphitheatre (marked K) and the Bishop's Palace. Correct us if we're wrong, but isn't it the spitting image of the courthouse, (which was opened in June 2001)? Compare it with the above aerial photograph- it is certainly of similar scale and on the same alignment, parallel with Souter's Lane. Here's a curiousity. While perusing a recently-acquired copy of Chester, a guidebook published by Pevensey Heritage Guides (a branch of Reader's Digest), we were attracted by a large, painted 'aerial view' of our fine city- a detail of which is reproduced here- but were surprised by the appearance of a large building shown standing between the amphitheatre (marked K) and the Bishop's Palace. Correct us if we're wrong, but isn't it the spitting image of the courthouse, (which was opened in June 2001)? Compare it with the above aerial photograph- it is certainly of similar scale and on the same alignment, parallel with Souter's Lane.

As we learned much earlier, news of the court's planned construction was first presented as a fait accompli to an unbelieving public in early January 2000- but our edition of the book was published seven years earlier, in 1993! We've since been advised that the structure is probably the long-demolished science block of the old school. The resemblance to today's eyesore, nontheless, remains remarkable...

In late January 2002, an exciting new approach was taken to finding out what mysteries remain beneath the ground when a team from GSB Prospection of Bradford, working with the council's Chester Archaeology, embarked upon a survey of the amphitheatre site using a technique called Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), which works by sending pulses of electromagnetic energy through the soil. Reflections are sent back as the waves pass through the boundary between materials of differing densities, so that foundations show up against the earth in which they are buried. Unfortunately, the technique cannot be used on the areas covered by the courts and Dee House because of the presence of wooden and reinforced concrete floors.

Once the survey has been completed and the findings analysed, it is hoped that an accurate picture will be built up of what lies buried across much of the rest of the site- how much of the amphitheatre survives and the positions of later structures that have occupied the area since its demise some 1,650 years ago. The survey has been inspired by Keith Matthew's small-scale excavations over the last couple of years which revealed that parts of the Roman monument were in much better condition than had been expected- by some, at least.

An extension of GPR, known as slice-mapping, is also to be used to generate plans of the site at different depths. Not only woud this help tp show the heights of remaining walls, but it could also reveal the presence of post-Roman structural remains at higher levels.

As if we needed any more contributions adding to the complex web of competing interests here, also in late January 2002 we heard that a rare tree had been found growing in the centre of the Dee House grounds! This 'Tree of Heaven' (Ailanthus Altissima) has roots that bury deep into the ground before rising up to form the trunk of a second tree only yards from the parent. It originated in the Orient and Australia and was introduced into England in the mid-18th century as an ornament and then to the United States in the early 19th century for their (eventually abandoned) silk industry. Its leaves are the preferred food of the Ailanthus Silk Moth, which is different from the common domesticated silkworm which feeds on mulberry leaves. The silk unwound from Ailanthus cocoons wears much better than that of the common silkworm but is not so soft and glossy. As if we needed any more contributions adding to the complex web of competing interests here, also in late January 2002 we heard that a rare tree had been found growing in the centre of the Dee House grounds! This 'Tree of Heaven' (Ailanthus Altissima) has roots that bury deep into the ground before rising up to form the trunk of a second tree only yards from the parent. It originated in the Orient and Australia and was introduced into England in the mid-18th century as an ornament and then to the United States in the early 19th century for their (eventually abandoned) silk industry. Its leaves are the preferred food of the Ailanthus Silk Moth, which is different from the common domesticated silkworm which feeds on mulberry leaves. The silk unwound from Ailanthus cocoons wears much better than that of the common silkworm but is not so soft and glossy.

The tree's roots are believed to be toxic and often find a way to penetrate into wells and springs. The crushed leaves have an unpleasant 'peanut butter' odour. American websites, such as this, speak of the Ailanthus as naturalised and very common- "the tree of cities"- ideal for polluted environments where other species would not thrive. Here in the UK, it is often found in gardens in the south of England and East Anglia- and, nearer to home, several specimens thrive just yards away in Grosvenor Park. Not so rare after all, it seems!

Right: this recent photograph graphically illustrates the current condition of the entrance hall and staircase of Dee House

Nontheless, some people are apparently calling for the imposition of a preservation order on the 50 year-old Dee House Ailanthus while others believe it would be feasable for it to be moved to another location- possibly to join its kin in the park- where it would be safe from excavators and developers.

A further council meeting was held on the 27th February 2002 to discuss the future of Dee House, which was remarkably described in the Chester Standard the following day as "now lying empty and no one has expressed an interest in using the site". No one? What about those lovely offices and wine bars we were hearing so much about from council planners and McLean's not so long ago? A further council meeting was held on the 27th February 2002 to discuss the future of Dee House, which was remarkably described in the Chester Standard the following day as "now lying empty and no one has expressed an interest in using the site". No one? What about those lovely offices and wine bars we were hearing so much about from council planners and McLean's not so long ago?

The tone of the entire debate now, however, seemed to have changed and the idea of an "early" demolition was being openly discussed. Should this actually come about, it would enable the excavation and display of a large additional portion of the amphitheatre, including another 25% of the seating bank and nearly all the hidden portion of the arena. Remains which, not so long ago, the 'experts' were telling us had long since largely been swept away by the construction of Dee House.

Perhaps some of this sudden change in attitude was the result of a city council report which, as the Standard reported it, "has given a rather grim outlook for the crumbling Dee House". To say the least.

The more aware councillors were doubtless also impressed by the remarkable findings of the small scale excavations carried out over the last couple of seasons by Keith Matthews and his team, which have shown that far more of the monument survives than had been previously thought, even in those areas which had been subjected to the heavy-handed treatment of the excavators of the 1960s. And greater things by far are expected of his radar survey of the portion of the amphitheatre still lying hidden beneath the grounds of Dee House.

We also hear rumours that, with the coming of a new supremo to English Heritage, even they are viewing the putting of Dee House out of its misery with greater sympathy. Full excavation, of course, will never happen until the courthouse is acquired and consigned to the oblivion it so richly deserves- a situation which, the apologists tell us, is unlikely to come about for at least a quarter of a century, during which time the monotonous end wall of the courthouse- never designed to actually be seen- will become the dominating visual feature of the entire area, a blot on the landscape to be wondered at by visitors from all over the world for years to come.

Perhaps they'll try to tart it up by sticking the horrible concrete 'decorations'- so admired by the Civic Trust- from the end of the soon-to-be-demolished Police HQ on to it...

At the beginning of November 2002, the local press had some very good news to report- an "exciting new scheme" that would, at long last, apparently lead to the full excavation of Chester's amphitheatre! The proposals involve carrying out a two-stage excavation of the historic site, along with the construction of a state-of-the-art interpretation and visitor centre that would also- you guessed it- house restaurants, cafes and shops. At the beginning of November 2002, the local press had some very good news to report- an "exciting new scheme" that would, at long last, apparently lead to the full excavation of Chester's amphitheatre! The proposals involve carrying out a two-stage excavation of the historic site, along with the construction of a state-of-the-art interpretation and visitor centre that would also- you guessed it- house restaurants, cafes and shops.

All this with, we're told, with the approval of the Chester Amphitheatre Trust. Their Chairman, Dr Lian Smith said: "We are really pleased with the proposal, it's what we have been seeking for some time. A two phase programme is the most sensible route, given the siting of the County Court, and it makes sense to get started on the first stage".

If approved, the first phase of the scheme couid be carried out within the next two to three years and would involve the demolition of Dee House, the derelict listed building that covers part of the site. "We have been fighting to have Dee House demolished and are very supportive of this proposal" added Dr Smith.

The demolition would be followed by "community-led" excavations to unearth the part of the site under which Dee House currently stands.

Construction of the first phase of a two-stage building, wrapping around the western flank of the monument, would also follow. This would house an interpretation centre, restaurant and cafe, and would include a roof terrace for the restaurant overlooking the amphitheatre. The proposals apparently envisage an "imaginative" (oh-oh) design using 'contemporary' architecture.

The second phase of the scheme would involve the council acquiring- and demolishing- the recently built County Court- a longer term initiative that could take "up to 15 years or more" to complete, depending upon negotiations to acquire the building.

Added Dr Smith, "The building (the County Court) sits on about three per cent of the site and the car park covers about 20 per cent, but until the lease runs out in 15 years' time, the second phase of the programme cannot begin and part of the amphitheatre remains covered". Added Dr Smith, "The building (the County Court) sits on about three per cent of the site and the car park covers about 20 per cent, but until the lease runs out in 15 years' time, the second phase of the programme cannot begin and part of the amphitheatre remains covered".

Further excavations could then be carried out to unearth the remaining part of site, and construction of phase two of the visitor building, wrapping around the southern side of the amphitheatre, would get under way.

Left (and below): It's gone! The top part of the unsightly wall separating the two halves of the site was removed in June 2004.

City councillor Ann Farrell, portfolio holder for culture and heritage, said: "The city council decided some time ago to commit itself to the full excavation of the amphitheatre and, as a result, the demolition of Dee House. The council has been exploring ways to do this and has been holding talks with its partners. This has taken some time due to the size and importance of the issue, but we now have a proposed scheme that paves the way for the full excavation of the amphitheatre- something for which there is strong public support. The proposals underline the city council's committment to taking the lead on the amphitheatre issue and although many of the details still need to be ironed out, the principles of the scheme set out a clear vision for the future of one of Chester's most important historic sites".

The City Council is expected to take the lead in promoting and securing funding for the scheme, but the Amphitheatre Trust intends to remain very active. Dr Smith observed, "It looks like we are about to achieve what we set out to do, and that really excites us, but we are not giving up campaigning. A scheme such as this needs continuous monitoring to ensure it is done correctly, and we are anxious to stay fully involved to make sure this is the case".

11th September 2003: Some time has elapsed since additions have been made to these pages. In truth, and despite the above fine sentiments, very little debate over the future of the amphitheatre and its surroundings- in the local press or within the council chamber- took place over this period. The latest batch of letters, mostly originating from the tireless pen of Alan Bonner (currently, it seems, the sole correspondent upon the matter) should suffice to bring you up to date with 'progress', pathetic though it may be.

16th June 2004: How time flies! We're getting into the habit of apologising for the lack of decent updates to these pages... but now, at least, we can happily report that things are at last, after a fashion, moving. Excellent new information boards have appeared around the site and the upper half of the unsightly wall dividing the excavated half of the amphitheatre from the Dee House grounds has been demolished and replaced with a walkway from which visitiors to the site may soon observe the work of the team of archaeologists who commenced their labours here at the beginning of this month.

14th July 2005: The second year of excavation at the amphitheatre is now under way, attracting lots of visitors and, during June, becoming the subject of a BBC Timewatch TV special. We, along with, we can only imagine, many other viewers were intrigued that, while much attention was paid to the relatively small area currently under the trowel- "grubbing through the backfill of 1960s bulldozers" as one archaeologist not serving the city council or English Heritage put it (not entirely fairly as remarkable new discoveries are being made) - no mention was made of the rest of the site- most especially the half still overlaid by Dee House and that court building. We enjoyed spectacular aerial views of a patently semi-circular monument but were supplied with no explanation of why this should be. Discerning viewers living outside Chester, and therefore unaware and uninformed of the sorry politics that continue to lie behind it all, must have been mystified.

After many years, Dee House is once again lit up and occupied, utilised by the archaeologists for tool storage, find sorting/cataloguing, tea making and the like. Some would say that this sets a precedent for the future use of the building- no longer derelict and dangerous it seems, but safe for occupation and ripe for redevelopment. No surprises there then. After many years, Dee House is once again lit up and occupied, utilised by the archaeologists for tool storage, find sorting/cataloguing, tea making and the like. Some would say that this sets a precedent for the future use of the building- no longer derelict and dangerous it seems, but safe for occupation and ripe for redevelopment. No surprises there then.

Right: The amphitheatre in June 2004- now minus the boundary wall. The scene, depressingly, still looks much the same five years later- May 2009- except for the unsightly mass of gravel which has replaced the lawn on the right which, inexplicably, hasn't been restored since the dig four years previously. Naturally, the decay of Dee House continues apace...

This writer, just the other night, was accused by one of the directors of the current excavation of perpetuating a myth that there actually are viable remains of the other half of the amphitheatre remaining beneath Dee House and the Court House. Their research having 'proven' that this, remarkably, is not the case! Astonished by this claim, I shortly afterwards consulted three eminent Chester archaeologists, Dr David Mason, Keith Matthews and Mike Emery, all of whom have excavated here in the past- and all of whom absolutely disagreed with this outrageous statement. The Chester Chronicle, too, was accused by the gentleman of "falsely raising people's expectations that wonderful remains were yet awating discovery". Both this author and the local press, I was brusquely informed, "don't know what they're talking about".

So it's probably best at this point, dear reader, to advise that you forget everything you've read so far and get straight over to the City Council's own Chester Amphitheatre Project website, where everything is lovely and true. No, really.

(However, on our most recent visit in February 2009, we noticed that the site had not been updated at all since the Summer of 2007)

"Democracy has another merit, it allows criticism, and if there isn't public criticism, there are bound to be hushed-up scandals". E M Forster (1879-1970)

On to part XI of the Amphitheatre story or move on to the ancient and beautiful Church of St. John the Baptist... |

s we have previously heard, Past Forward, best know for the Jorvik Centre in York have already estimated that a fully-excavated amphitheatre and quality visitor centre could turn the site into "an innovative visitor attraction of regional and national significance" attracting around 180,000 visitors per year. Their findings were published in September 2001 and the following is a summary:

s we have previously heard, Past Forward, best know for the Jorvik Centre in York have already estimated that a fully-excavated amphitheatre and quality visitor centre could turn the site into "an innovative visitor attraction of regional and national significance" attracting around 180,000 visitors per year. Their findings were published in September 2001 and the following is a summary:

Here we see a fascinating aerial photograph of the Chester amphitheatre as it appeared during the late summer of 2001. Even more clearly than

Here we see a fascinating aerial photograph of the Chester amphitheatre as it appeared during the late summer of 2001. Even more clearly than

Regarding the current condition of Dee House (illustrated right and see interior view below), we have spoken to two individuals- one of them a County Councillor- who have looked around the building since Christmas. They were both horrified by the state of the interior, apparently far worse than they have been led to believe. The entire structure is apparently being held up by immense amounts of scaffolding, rows of which are placed three feet apart on all three stories, each holding up the floor above it.

Regarding the current condition of Dee House (illustrated right and see interior view below), we have spoken to two individuals- one of them a County Councillor- who have looked around the building since Christmas. They were both horrified by the state of the interior, apparently far worse than they have been led to believe. The entire structure is apparently being held up by immense amounts of scaffolding, rows of which are placed three feet apart on all three stories, each holding up the floor above it. Here's a curiousity. While perusing a recently-acquired copy of Chester, a guidebook published by Pevensey Heritage Guides (a branch of Reader's Digest), we were attracted by a large, painted 'aerial view' of our fine city- a detail of which is reproduced here- but were surprised by the appearance of a large building shown standing between the amphitheatre (marked K) and the Bishop's Palace. Correct us if we're wrong, but isn't it the spitting image of the courthouse, (which was opened in June 2001)? Compare it with the above aerial photograph- it is certainly of similar scale and on the same alignment, parallel with Souter's Lane.

Here's a curiousity. While perusing a recently-acquired copy of Chester, a guidebook published by Pevensey Heritage Guides (a branch of Reader's Digest), we were attracted by a large, painted 'aerial view' of our fine city- a detail of which is reproduced here- but were surprised by the appearance of a large building shown standing between the amphitheatre (marked K) and the Bishop's Palace. Correct us if we're wrong, but isn't it the spitting image of the courthouse, (which was opened in June 2001)? Compare it with the above aerial photograph- it is certainly of similar scale and on the same alignment, parallel with Souter's Lane. As if we needed any more contributions adding to the complex web of competing interests here, also in late January 2002 we heard that a rare tree had been found growing in the centre of the Dee House grounds! This 'Tree of Heaven' (Ailanthus Altissima) has roots that bury deep into the ground before rising up to form the trunk of a second tree only yards from the parent. It originated in the Orient and Australia and was introduced into England in the mid-18th century as an ornament and then to the United States in the early 19th century for their (eventually abandoned) silk industry. Its leaves are the preferred food of the Ailanthus Silk Moth, which is different from the common domesticated silkworm which feeds on mulberry leaves. The silk unwound from Ailanthus cocoons wears much better than that of the common silkworm but is not so soft and glossy.

As if we needed any more contributions adding to the complex web of competing interests here, also in late January 2002 we heard that a rare tree had been found growing in the centre of the Dee House grounds! This 'Tree of Heaven' (Ailanthus Altissima) has roots that bury deep into the ground before rising up to form the trunk of a second tree only yards from the parent. It originated in the Orient and Australia and was introduced into England in the mid-18th century as an ornament and then to the United States in the early 19th century for their (eventually abandoned) silk industry. Its leaves are the preferred food of the Ailanthus Silk Moth, which is different from the common domesticated silkworm which feeds on mulberry leaves. The silk unwound from Ailanthus cocoons wears much better than that of the common silkworm but is not so soft and glossy.

Added Dr Smith, "The building (the County Court) sits on about three per cent of the site and the car park covers about 20 per cent, but until the lease runs out in 15 years' time, the second phase of the programme cannot begin and part of the amphitheatre remains covered".

Added Dr Smith, "The building (the County Court) sits on about three per cent of the site and the car park covers about 20 per cent, but until the lease runs out in 15 years' time, the second phase of the programme cannot begin and part of the amphitheatre remains covered". After many years, Dee House is once again lit up and occupied, utilised by the archaeologists for tool storage, find sorting/cataloguing, tea making and the like. Some would say that this sets a precedent for the future use of the building- no longer derelict and dangerous it seems, but safe for occupation and ripe for redevelopment. No surprises there then.

After many years, Dee House is once again lit up and occupied, utilised by the archaeologists for tool storage, find sorting/cataloguing, tea making and the like. Some would say that this sets a precedent for the future use of the building- no longer derelict and dangerous it seems, but safe for occupation and ripe for redevelopment. No surprises there then.